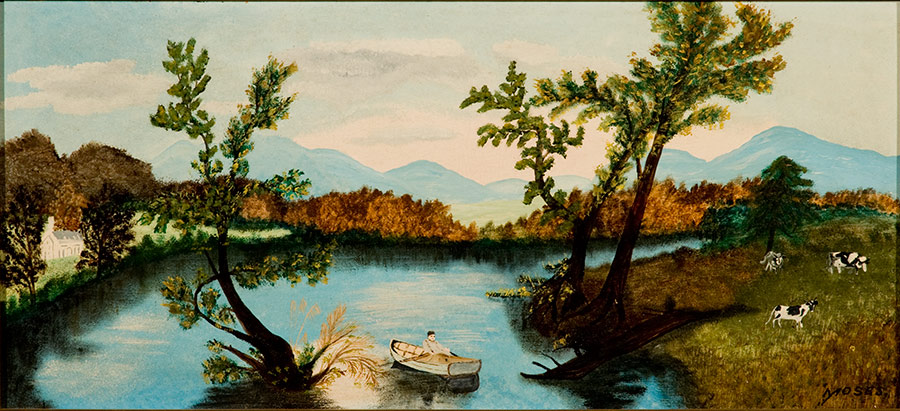

Last week, I wrote about the shifting American taste in modern art at the middle of the twentieth century. I’d like to revisit that subject again this week, prompted by my research on one of the most famous—and, in her own way, most controversial—artists of the last century. I’m talking, of course, about Anna Mary Robinson “Grandma” Moses. You may be wondering to yourself how Grandma Moses, one of the most popular and beloved American artists of all time, could be considered controversial. It all has to do, as we shall see, with the situation of American modernism at the time of her rise to prominence.

The story of Moses’s “discovery” by the art world is so well-known as to approach legend. Briefly, she started painting after the death of her husband, in part because moths kept destroying her needlepoints and other textile arts, and painting in oil on Masonite promised to be more durable. She did not sell her work, though she maintained a display in a drugstore near her home in Hoosick Falls, in Upstate New York. By chance, a New York collector and dealer named Louis Caldor happened upon the works, immediately buying all of them, as well as all of the paintings Moses had on hand at her farm. Caldor set about showing her work to a variety of gallerists in Manhattan, most of whom were not interested. Finally, Caldor piqued the interest of a recent Austrian immigrant named Otto Kallir, who agreed to put on a small show of Moses’s works.1 This show was briefly on display at the Museum of Modern Art, but Moses’s first real brush with celebrity did not come until somewhat later, when Gimbel’s Department Store featured her for its 1941 Thanksgiving Festival, where it displayed her paintings alongside a table loaded with her homemade bread, jam, and cakes. It was here that the press first discovered her direct, blunt, and yet also slyly mischievous personality, and an artistic celebrity was born. 2

Moses’s newfound fame came at something of an inflection point in the history of American modernism. In the late 1930s and early 1940s, Regionalism was still the dominant American artistic style, though the strong hegemony it had enjoyed earlier in the Great Depression era was starting to wane. Regionalism’s popularity prompted an interest in painters who shared its seemingly authentic view of the American heartland, including artists like Moses, to whom the names folk, primitive, self-taught, and naïve have been variously appended. No less an institution than the Museum of Modern Art featured several exhibitions dedicated to folk art during this period, featuring not just Moses but other artists like Horace Pippin and John Kane.3 In fact, Moses’s art seemed to many observers to share many features with modernism, including its rejection of the usual modes and strictures of the art world, its insistent flatness and denial of pictorial illusionism, and its so-called “primitive” aspect, which had been a key component of modernism since the beginning of the century. She was even paired in some critic’s minds with Jackson Pollock, with her visual style serving as a complement to the Abstract Expressionist’s seemingly intuitive, untrained spilling and dripping of paint.4

Aaron, 1941, Lithograph on wove paper,

12 7/8 in. x 9 1/2 in. print, Purchased by the Friends and Partners of the Cornell Acquisitions Fund © Thomas Hart Benton/Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York 1993.5

Ultimately, it was not to last. The art world, led by the critic Clement Greenberg, began to favor pure abstraction, which caused a deep antipathy towards Regionalist and folk painters alike.5 Luckily for Grandma Moses, however, she had something that allowed her popularity to endure well past her death at the age of 101 in 1961, something that even Regionalists like Thomas Hart Benton lacked: mass appeal.6 Otto Kallir, her first gallerist, registered her paintings with the United States Copyright Office, at that time a relatively unconventional step for a painter. Using those designs, he established a company to license her work, resulting in hugely successful lines of greeting cards, decorative china, curtains, and other housewares. It was this line of goods, which brought her serene depictions of simpler times in the American countryside to an audience newly grappling with the anomie of the postwar suburbs, that ultimately has sealed Anna Moses’s legacy, and which continues to make her one of the most beloved and popular artists in the United States.7 She may have missed out on canonization at MoMA, the shrine of American modernism, but her story is itself a uniquely modern, uniquely American one.

1 Jane Kallir, “Introduction: Rethinking Grandma Moses,” in Grandma Moses in the 21st Century, by Jane Kallir (New Haven, Conn.: Yale Univ. Press, 2001), 20–23.

2 Judith E. Stein, “The White-Haired Girl: A Feminist Reading,” in Grandma Moses in the 21st Century, by Jane Kallir (New Haven, Conn.: Yale Univ. Press, 2001), 52–53. Moses’s trip to the city for the occasion marked the first time she had been to Manhattan since 1917.

3 Katherine Jentleson, Gatecrashers: The Rise of the Self-Taught Artist in America (Oakland, California: University of California Press, 2020), 5. Jamie Franklin, “Moses, MoMA, and the Modernist Narrative,” in Grandma Moses: American Modern (New York: Skira Rizzoli, 2016), 9–11.

4 Franklin, “Moses, MoMA, and the Modernist Narrative,” 12–15. Recent scholarship has shown that Pollock was actually much more cerebral than his public image let on, but at the time the two were spoken of in these terms.

5 Michael D. Hall, “Picturing Myth and Meaning for a Culture of Change,” in Grandma Moses in the 21st Century, by Jane Kallir (New Haven, Conn.: Yale Univ. Press, 2001), 41–42.

6 Hall, 43.

7 Thomas Andrew Denenberg, “The New Detached House: Grandma Moses and 1950s America, Thomas Denenberg,” in Grandma Moses: American Modern (New York: Skira Rizzoli, 2016), 95–124.