The exhibition Fake News? Some Artistic Responses covers a selection of American artists’ reaction to the world of mass media from the early 20th century to the present day. A phrase all too familiar in our everyday lives and coined only recently, “fake news” has manifested in different ways over time. From information taken out of context and twisted truths to unreliable sources and outright propaganda, inflammatory reports compromise reputable journalism and trust in democracy. Though this phenomenon has amplified in today’s era of a constant newsfeed, the media has been under critical scrutiny in the United States for over a century. Artists have often responded to, and reacted against, the way society collects, perceives, and shares information. Through their work, they offer research, report on current events, and act as the fact-checkers of their generations. With their voices, viewers are encouraged to exercise and strengthen their skills in information literacy.

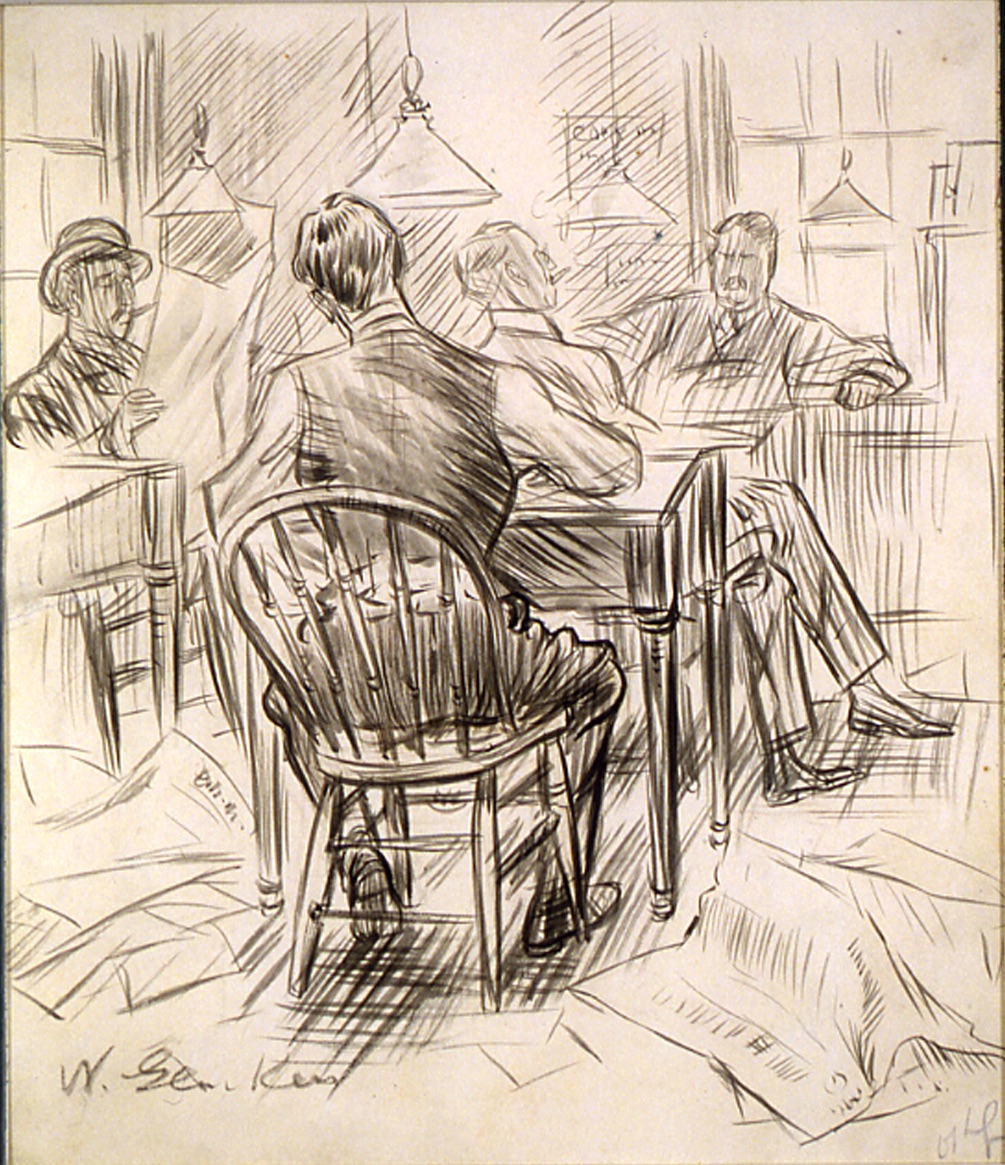

William James Glackens

The inspiration for the exhibition began with the work by William James Glackens (American, 1870-1938) titled Our American Snobs: The Relation of Yellow Journalism to Its Own Creation, the Four Hundred. William James Glackens is best known today as one of the Eight, a revolutionary group of early 20th-century artists based in New York who changed painting in the United States with their modern scenes of everyday life.

His dedication to realism in art perhaps began with his experience as an illustrator for various news outlets, including the Public Ledger, The Philadelphia Press, The New York Herald, the New York World, and McClure’s Magazine. Our American Snobs, which was published in The Saturday Evening Post in 1903, features a bustling scene with newspapers strewn across the floor. The title reveals Glackens’ criticism of the “snobs” of the “Four Hundred” and his stance on the dangers of yellow journalism. This term, developed in the period and believed to have started with the popular “Yellow Kid” cartoon in New York World and the New York Journal, referred to sensationalist headlines created to keep newspapers and magazines in circulation. New York City social elites who owned the newspapers and other forms of the press were mainly responsible for generating these salacious headlines for their own personal gain. These people were among the “Four Hundred,” a list originally established in 1872 by high-society figures Ward McAllister and Caroline Webster Astor. McAllister stated that “only about 400 people in New York society” were of importance, and coincidently, the maximum capacity of Astor’s ballroom held 400 guests. With this work, Glackens participated in a growing effort among artists and journalists of this era to expose corruption and encourage viewers to find the truth.

Jerome Meadows

This effort resonates deeply with the 2008 work An Underlying Truth, created just over a century later than the Glackens work, by contemporary, Savannah, Georgia-based artist Jerome Meadows (b. 1951, Bronx, New York). Meadows has focused his practice on large-scale art projects, sculptures, installations, and assemblages. Through this physically and metaphorically layered mixed media collage, Meadows approaches various fundamental political, sociological, and cultural issues in America.

At first glance, the patriotic American flag dominates the composition; upon further examination, intricate details emerge. The found objects that make up this assemblage — children’s toys, band-aids, photographs, and newspaper clippings — are full of nuance and suggest the tension between the innocence of the American public and the ever-present underlying political unrest. The title of this work, inspired by the 2006 documentary by former Vice President Al Gore, An Inconvenient Truth, inspires viewers to look beyond the surface and search for the facts.

How We Experience Information Today

Through the works in this exhibition, museum visitors thoughtfully consider the way we as a culture experience information, especially today. According to the American Alliance of Museums and the Museums R+D, Reach Advisors, “museums are considered the most trustworthy source of information in America, rated higher than local papers, nonprofits researchers, the U.S. government, or academic researchers,” so information literacy is essential in this field.1 A resource guide on information literacy accompanies the exhibition and is available at the museum. As an academic institution, it’s critical to not only engage in socially conscious exhibitions that reflect pressing issues of our immediate but also provide exhibitions that directly serve the needs of the community. Ultimately, the museum is a democratic, safe space for dialog and one that nurtures expression, learning, and sharing the facts.

1American Alliance of Museums, “Museum Facts & Data,” Accessed November 5, 2018. https://www.aam-us.org/programs/about-museums/museum-facts-data/#_ednref23