This post was written in 2019 and has been edited to update pertinent information.

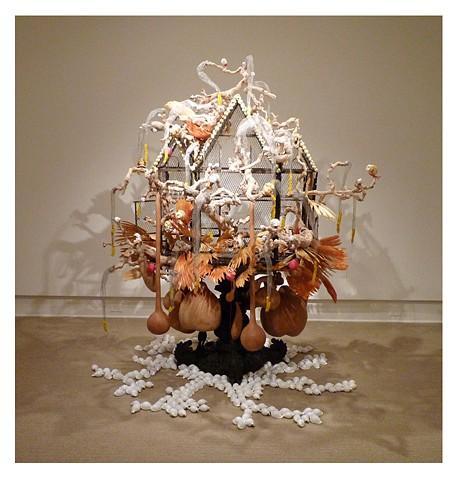

Rina Banerjee’s Her captivity was once someone’s treasure… combines historical objects (a Victorian birdcage, a 19th-century New England table) with elements both natural (gourds, feathers, shells, coral), and man-made (doll heads, glass beads). The resulting sculpture possesses an eclectic architecture and a multi-storied presence. The various symbolic narratives woven tightly by an artist equally comfortable with real and imaginary worlds, and extremely adept at fusing disparate elements, reveal themselves slowly and in different ways depending on context.

Rina Banerjee (American, b. Kolkata, West Benghal, India, 1963)

Her captivity was once someone’s treasure and even pleasure but she blew and flew away took root which grew, we knew this was like no other feather, a third kind of bird that perched on vine intertwined was neither native nor her queens daughters…, 2011

Anglo-Indian pedestal 1860, Victorian birdcage, shells, feathers, gourds, grape wine, coral, fractured charlotte doll heads, steel knitted mesh with glass beads (83 7/8 x 83 7/8 x 72 in)

Museum purchase from the Michel Roux Acquisition Fund, 2016.20

I first saw this sculpture in the Rollins Museum of Art (formerly Cornell Fine Arts) exhibition Displacement: Symbols and Journeys (summer 2016). There, in the context of a narrative about ethnic and cultural identity, borders and boundaries, it seemed to both embody and reject the notion of cultural confluence. Did all the disparate elements go together, suggesting the possibility of assimilation and fusion, or did they painfully underline the “otherness” that each presented to the other? Was the open door of the cage a hopeful sign of freedom or did it simply remind us that it can close at any time?

The sculpture was one of the works that engendered the most dialogue with students and visitors, and we decided to acquire it for the collection.

(Image: Displacement: Symbols and Journeys at Rollins Museum of Art)

Shortly after, we installed it in the Education Gallery, where it welcomed you in the context of other sculptures from the collection and children’s art engagement stations. There, Her captivity…. spoke to the expansiveness of art and the ways in which it opens entire worlds for exploration, but also to materials and materiality, art making, and the process of slow discovery we teach our youngest visitors.

Note: Since the publication of this post, this work by Rina Banerjee was featured in Rollins Museum of Art’s 2023 exhibition In Our Eyes: Women’s, Nonbinary, and Transgender Perspectives from the Collection. You can view this exhibition in a 360 degree virtual view here.

Partnering with Pennsylvania Academy of Fine Arts

Credit: Courtesy of the Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts/Barbara Katus

In the summer of 2018, the Banerjee sculpture moved again as we agreed to lend it to the Pennsylvania Academy of Fine Arts (PAFA) for a major retrospective of the artist titled Make Me a Summary of the World. At PAFA, Banerjee’s works were not installed in a separate gallery, but rather interspersed throughout the permanent collection, interacting with it. Our sculpture is installed in a gallery dedicated to Colonialism and its Legacy; it fills the physical space of the doorway between staid historical portraits. Metaphorically, it fills a much larger space: not only does it symbolize the legacy of Colonialism, it also reminds us of all the unsung women artists during the early history of the United States. It presents itself – in sharp contrast to that period – as embodiment of the transnational nature of the contemporary art world.

Changing Contexts Changing Meanings

As we celebrate Women’s History Month this March, it occurs to me that Rina Banerjee’s Her captivity…, with its multi-layered meanings, some initially hidden, may also speak to the very essence of female artists. Depending on the times, women could hardly become artists; in the Renaissance and Baroque periods, when and if they did, they had to ask their husbands or fathers to buy paints and other supplies. And even when they could buy their own paints, they were always eclipsed by male family members who were artists. In the early 1930s, a Detroit newspaper called Frida Kahlo “the wife of the master mural painter,” who “gleefully dabbles in works of art.” Until very recently, many women artists – most? – were marginalized or completely left out of the art historical narrative.

Women Artists Today

Things are sadly not that much better today. Even stories that show progress present complicated realities. In 2018, a painting by Artemisia Gentileschi made headlines as it was purchased for a record price ($4.6 million) by the National Gallery in London (see one of our blog posts, here). Yet it was the first painting by the celebrated 17th-century artist to enter the collection of the National Gallery; worse still, it was only the 26th work by a woman in a collection numbering 2,300.

In 2019, a painting by Carmen Herrera sold for $2.9 million (well above the estimate of $2 million) at Sotheby’s. Let us not forget, however, that Herrera only got the attention of the art world when she was in her eighties, after a lifetime of painting (read more about Herrera here).

Exhibitions of women artists continue to lag significantly behind those of their male counterparts (as of 2000, the Guggenheim Museum in New York had no solo exhibitions by women) and works by female artists sell for at least 45% less than their male artists at auction. The list goes on. But women persist. And with every step forward, the glass ceiling breaks a little more. This is why we celebrate the (female) curators at PAFA and the San José Museum of Art who organized the extraordinary exhibition Make Me a Summary of the World, the first in-depth exploration of Rina Banerjee’s artistic practice.

National Museum of Women in Arts

We are proud to be among the more than 300 institutions from 50 states, 25 countries, and 6 continents who have partnered with the National Museum of Women in the Arts in their #5WomenArtists campaign to raise awareness and take action that will help advance gender equity in the arts. Join the conversation.

Learn more about Rina Banerjee

Learn more about the exhibition Make Me a Summary of the World via Studio 360.

Image Courtesy of the Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts/Barbara Katus

Rina Banerjee shares details on the work “A lady of commerce…” featured in the Rollins Museum of Art (formerly Cornell Fine Arts) 2016 exhibition Displacement: Symbols and Journeys via CFAM in 60 Seconds