A few weeks ago, I wrote about Wayne Thiebaud, whose career has been much more varied than I had previously understood. This week, I’ve had the opportunity to consider another such artist, the similarly underappreciated Tom Wesselmann. If Thiebaud is best known today for his early paintings of sticky-sweet confections, Wesselmann is undoubtedly known for this long-running exploration of the nude, in particular in his Great American Nude series, which paired the colors of the American flag with a frank eroticism uncommon even in the libertine 1960s. It was these works that first brought Wesselmann attention as part of the Pop generation that also included Andy Warhol, James Rosenquist, and Roy Lichtenstein, among others. Like fellow Cincinnatian Jim Dine, Wesselmann expressed discomfort with his inclusion in the group, though to my eye (and to those of many scholars) his inclusion makes a good deal of sense. After all, Wesselmann’s nudes are often accompanied by iconic American consumer goods—in particular cigarettes—in addition to being rendered in the same crisp, hard-edged style explored by his contemporaries.1 As my research—and a perusal of the three prints by Wesselmann in the CFAM collection—reveals, however, Wesselmann was actually much more than just a painter of heroically scaled naked women.

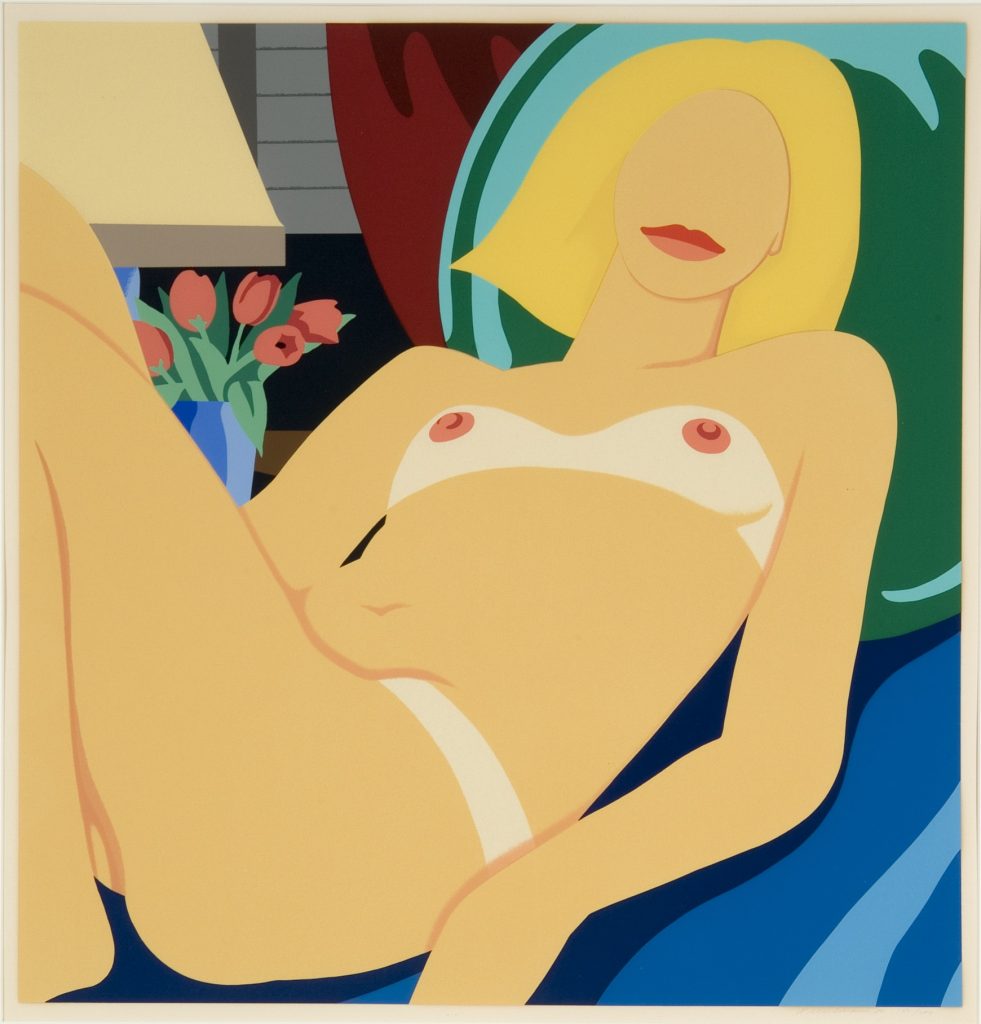

First, though, a word or two about those nudes. As scholars on Wesselmann note, the nude has a long tradition in the history of Western art.2 Wesselmann first began investigating the motif during a turbulent time in his life, just after the end of his first marriage. Under the care of a psychoanalyst—recommended by Dine—he began to explore his interest in sexuality. He was further inspired by his future wife, Claire, who was the model for all of the early Great American Nudes.3 His interest in the nude was also informed by the history of art, in particular the hopelessness he felt while viewing the work of Willem de Kooning at the Museum of Modern Art (the young Wesselmann felt de Kooning had already accomplished all that could be accomplished in painting) and what he termed his daily and lifelong conversations with Henri Matisse.4 It is this latter painter who seems most to inform Claire Nude, the work in lithograph and silkscreen in the CFAM collection. His wife lounges poolside, gazing directly out at him (and us), though he has chosen to efface her eyes in favor of lips and breasts—a signature Wesselmann move. The model’s pose and the bright planes of color reveal the influence of Matisse, seeming to blend the French master’s early nudes—like Petit Bois Clair, in the collection—with his late work in flat paper cutouts.

Wesselmann, who died in 2004, was the only major artist of the Pop generation never to receive a retrospective exhibition in North America during his lifetime, an oversight which was not rectified until the Montreal Museum of Fine Arts held one in 2012.5 His lack of critical attention apparently wore on him, especially because it caused a lack of understanding of the full breadth and depth of his work in much of the art-loving public and, indeed, if my example is any indication, among art historians as well. Luckily for posterity, he kept working.6 The collection includes a wonderful print based on his series of cut-metal land- and seascapes, though unfortunately we do not have an image available for it as of this writing. These works were a source of real creative energy and prodigious output for Wesselmann, as were his series of paintings, prints, and sculptures depicting smokers. Smoker, a 1976 silkscreen, is a perfect example of the latter, which blend his interest in the erotic with his knowing critique of American pop culture and capitalism. Even as Wesselmann focuses on his model’s lips and the sensuous curls of smoke that seem to envelop her face, there is also a touch of the monstrous about the picture. The massive, curled fingers and yellowy teeth give the image a touch of danger, even rot, reminding us of the sharp mind and critical eye behind the painter who originally paired explicit nudity with the colors of the American flag.

1 Tom Wesselmann and Michael Lobel, Tom Wesselmann (Exhibition Tom Wesselmann, New York, NY: Mitchel-Innes & Nash, 2016), 101–2.

2 Tom Wesselmann and Stéphane Aquin, Tom Wesselmann (Montreal : Munich ; New York: Montreal Museum of Fine Arts ; DelMonico Books, Prestel, 2012). John Wilmerding, Tom Wesselmann: His Voice and Vision (New York: Rizzoli, 2008).

3 Wilmerding, Tom Wesselmann, 38–39.

4 Sam Hunter, “Remembering Tom Wesselmann (1931–2004): And His Alter Ego, Slim Stealingworth,” American Art 19, no. 2 (2005): 109. Wilmerding, Tom Wesselmann, 21.

5 Wesselmann and Aquin, Tom Wesselmann.

6 Wilmerding, Tom Wesselmann, 178.