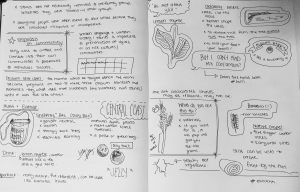

This past week in my Aboriginal Culture Class, I had the privilege of listening to several aboriginal identifying speakers who told me about their experiences and about the parts of their culture that they love. The Elder in Residence, Aunty Bronwin Chambers, laid out a huge table display of her own personal archive of artifacts from her family and culture. One by one she introduced the class to her dream stories, the fruits her people eat, the role she has as a grandmother, and the history of assimilation as it relates to her family. Some parts were sad of course, but her optimism prevailed as she guided us through her miniature museum. Perry, another aboriginal identifying speaker, beamed with pride of aboriginal culture, of the immense knowledge that they share with each other, initiations and ceremonies, and his role as an elder as well.

Throughout the entire three-hour lecture, there was a continuous thread that was woven through both presenters’ stories: the importance of mentorship. They didn’t use the term ‘mentor’, but they emphasized the older, or more experienced, helping to guide the younger generations and offering them useful advice. This advice may pertain to who to marry or what foods to eat and the advice was always practical. The main ways they pass down knowledge is through dance and music, drawings and sculpture, and, above all else, storytelling. This storytelling may be of their walk in the bush from that afternoon or about the ancestors creating the earth and these stories, no different from those in the Western World, are embedded with knowledge and lessons that help shape and guide us.

Throughout Australian history, just like through American history, many people have regarded indigenous groups as being exotic savages, lacking the sophistication and moral compass that European cultures have. As I sat there listening to their stories, absorbing the knowledge they were kind enough to offer me, I suddenly became aware of how similar their cultures are to ours as it relates to ritual estates (land owned by a certain family group), kinship systems (socially accepted understandings of how to interact with someone based on age, gender, or family relationship), sacred knowledge, and mentorship. This last element was the one that stuck out the most and that I hadn’t really thought about until this moment. At home, I’ve had so many different forms of mentors: grandparents, parents, aunts, uncles, cousins, neighbors, peer mentors, and professors, but never have I stopped and considered the impact they’ve had on my knowledge and development until now.

This past semester was probably the toughest semester I’ve ever had – not because of academics, but because of the events that had unfolded in my personal life that had all decided that fall of my sophomore year was the perfect time to coalesce and explode. For a short while I felt stuck and hopeless, stifled by my own anxieties and of a continuous repetition of some of my least fond memories. I had no idea where to turn, but I knew I had the professors in the art department to turn to for help – that was part of their job wasn’t it? My professors were wonderful and helped me find access to the support I needed, but it was one interaction between myself and my sculpture professor that really sticks with me.

It had been a terrible week, I have never experienced anxiety and depression like I had in the days leading up to my meeting with them. Eventually I grew weary and reached out to them and asked if they’d be free for a meeting- maybe a cup of coffee if they’d like. We scheduled a meeting for Monday morning to take a walk down to the local Starbucks on Park Ave. Already, the weight of what I was experiencing diminished, allowing me to transition into the weekend in a slightly better place. Monday morning rolled around and my anxiety was boiling as I grew nervous of how they would react to my situation. When they walked in, their typical cordial demeaner reminded me that they were on my side and were going to support me regardless of what happened. We put our stuff in their office and began our walk to the Starbucks. Walking to the coffee shop I told him my story, but it was on the way back that I think really made the difference.

My professor told me the story of their life, laying out a display of memories and inviting me to come closer. They shuffled through their own personal archive, they told me stories about when they were my age and how they managed their own situations. As they turned over each memory, as if a folio of an illuminated manuscript, they taught me the sensitivities one employs while interacting with the past and with pain. As they spoke, their words morphed into lyrics that I could carry with me and sing to myself when I needed them. As they walked, they performed a dance, teaching me what it looks like to have experienced so much and to still carry on, full of joy and sadness and still full of ambition and curiosity. By the end of our journey, the collection of stories that they had curated for this conversation filled me with the knowledge of how to pull myself back together and keep going.

This act of a mentor using their experiences and stories to help guide the younger generations is an act performed in so many cultures and is one that is immensely important. At the beginning of this course, I had the misconstrued notion that this was some characteristic exclusive to Indigenous groups – perhaps because of how I was taught and the exotic hues these cultures are painted in and then presented to us. I knew that we had mentors back home, but never considered the actual affect they have on mentees and the pivotal role they play in society. By creating this dialogue between the Aboriginal knowledge that I was given and the experiences I’ve had, a bridge was formed and I could understand their culture and realize that we weren’t so different- our cultures just looked different.

Experiencing another culture can be shocking and it can be easy to assume that the cultures are too different, but if you actively reflect on your experiences you may find their underlying structure or purpose more familiar than expected. This can help not only in understanding that culture, but all cultures as you seek a common ground between them to gain knowledge and help establish the blueprints for empathy. As a student of Rollins College who prescribes to their mission of global citizenship and responsible leadership, I find this connection between education and empathy to be paramount in realizing that mission. Over the course of my study abroad, I have witnessed the opportunities to engage in realizing this mission flourish as I’ve become more involved and hope there are more to come.

Until Next Time…