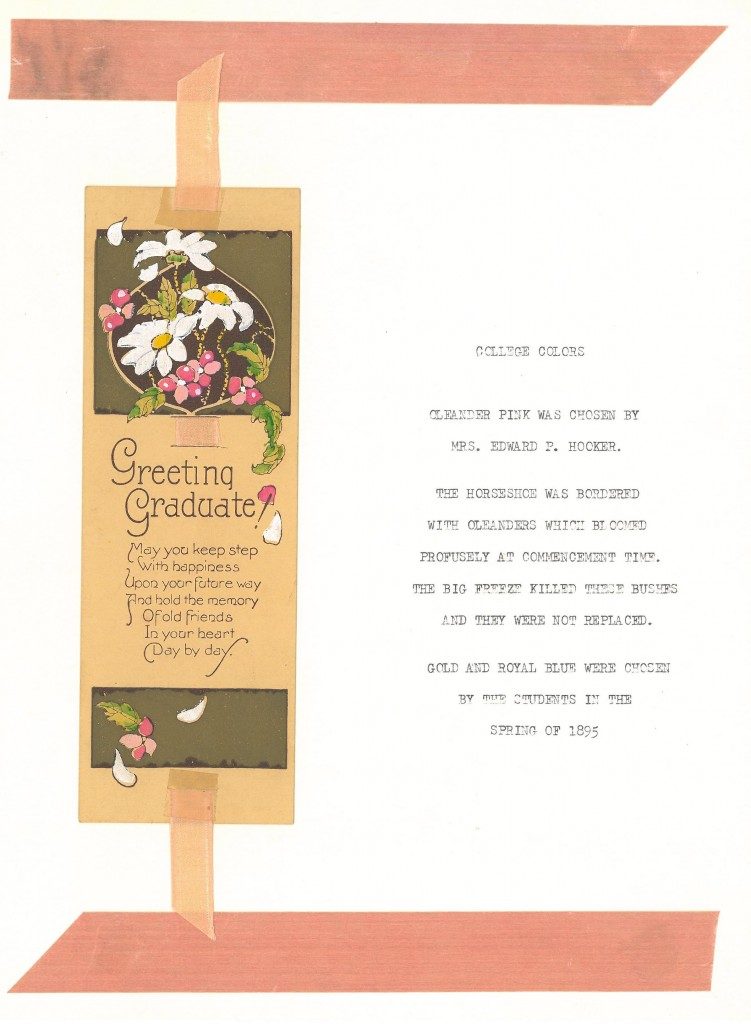

This keepsake in the Archives, decorated with faded pink ribbon, tells the story of Rollins’ first College color, oleander pink, and how it came to be replaced with the blue and gold that we know today. The text on the right reads:

College Colors

Oleander pink was chosen by Mrs. Edward P. Hooker.

The Horseshoe was bordered

with oleanders which bloomed

profusely at Commencement time.

The Big Freeze killed these bushes

and they were not replaced.

Gold and royal blue were chosen

by the students in the

spring of 1895

This is a short and simple account, but is there more to the story?

As is sometimes the case in such matters, there are different versions of events on record. One source says that the colors were changed in 1905; another states that the new colors appeared in 1908, inspired by the opening lines of the “Rollins Song” of 1907: “Fiat Lux! Let Rollins shine clear in the golden light of day.”

A more detailed account comes from Henry “Hank” Mowbray, class of 1897, the first editor of The Sandspur (and the future donor of Rollins’ Mowbray House). In an essay written in 1949, “Youthful Days in Florida,” he recalled the first part of the story told above: that Mrs. Hooker, the wife of Rollins’ president, had chosen oleander pink for the blossoms that appeared on campus at Commencement time. Then he added:

“But there arose complications for there was a fellow student of mine, Miss Marie McIntosh, who had a sallow and pimply complexion and who volubly contended that oleander pink was most trying for her to wear. Another complication was that I hoped. . . to secure the affections of Miss Marie. So to ingratiate myself with her, as editor of The Sand Spur, I waged a campaign against oleander pink and presented in print the advantages of Blue and Gold.”

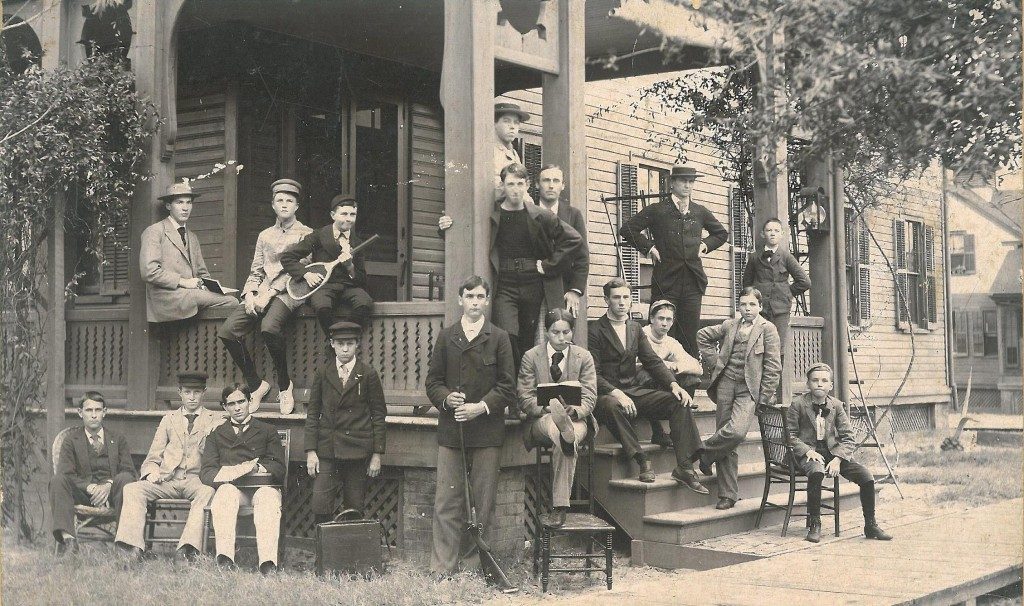

Henry Mowbray (seated, third from left) and fellow students at Pinehurst, 1894-95 (click on the photo to enlarge it)

Henry Mowbray (seated, third from left) and fellow students at Pinehurst, 1894-95 (click on the photo to enlarge it)

Just as Mr. Mowbray stated, the first issue of The Sandspur, published in December 1894, featured an article arguing for new school colors. The author, identified only by the initial “D.” (possibly art instructor Amy F. Dalrymple) first cited “the complaining whispers which the writer has heard for the past five years in regard to the college color,” and noted that “the rosewater pink which was selected and which Wanamaker promised to keep in stock for us, is not the color which we now use” and “the original color cannot be procured–a good reason for changing it.” After stating “the one strong objection to rose-pink is that it is felt to be inadequate to express dignity, strength, and stability,” The Sandspur went on to make this recommendation: “A charming combination of colors are royal blue and gold, each color giving force to the other by contrast. . . Let the royal blue suggest kingship, power, and the highest and deepest in character and aims, and let the gold mean to us, unchanging value, and real, substantial worth.”

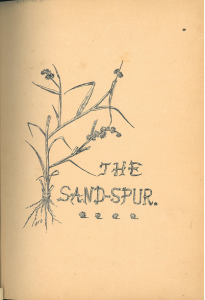

The cover of The Sandspur, 1894. Inside was the motto, “Stick to it.”

The cover of The Sandspur, 1894. Inside was the motto, “Stick to it.”

The Sandspur kept up the pressure in its next issue, which appeared in March 1895 and included a brief article arguing that “the new Rollins stick-pins which are seen displayed on lapels and other conspicuous places, surely show the weakness of the College color. Imagine pins of like pattern with gold mountings instead of silver; royal blue enamel instead of pink, and on the blue ‘Rollins’ or ‘RC’ in gold. It would be a pin to be proud of. . .” The same issue quoted a letter from alumnus Fred Lewton, who said in part, “though I should be sorry for the sake of old associations to have the color changed, I will say that I am in favor of something else,” as well as an update on the activities of The Demosthenic Society (publishers of the paper), who had unanimously voted for the new colors and appointed a committee to draw up a petition to submit to the faculty.

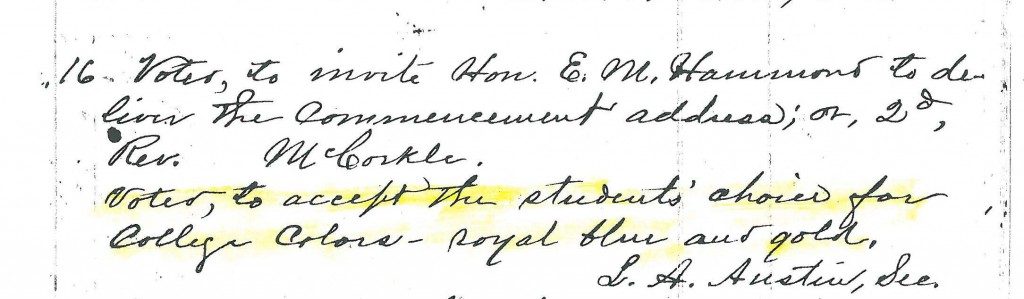

The minutes show that the faculty approved the change on April 16, 1895:

According to Henry, the campus had been “a tempest in teapot, made wild and stormy by Mrs. Hooker,” so the victory had been hard-won. Then came an unexpected blow: “It still brings tears to my eyes, and today I hope to your eyes, that after all this labor of mine, for her, the ungrateful Miss Marie transferred her affections from me to my rival, Ernest Missildine. How bitter life is!”

More than fifty years had passed, but even so, Henry claimed that “when these days I see Rollins students marching under blue and gold standards, I would that it were oleander pink.”

Henry Mowbray (front row, left) and fellow members of the Delphic Society, from a photo taken in 1894-95. Ernest Missildine is seated behind him. Author Rex Beach can be seen on the top right.

Henry Mowbray (front row, left) and fellow members of the Delphic Society, from a photo taken in 1894-95. Ernest Missildine is seated behind him. Author Rex Beach can be seen on the top right.

This would appear to be the definitive story of how the College colors came to be blue and gold, but one question remains: the Archives has no record of a student named Marie McIntosh. However, in yet another version of the story, published in 1952, The Sandspur reported that the change was first proposed by a student named Annie Fuller, who “hated pink. Rebelling against the insipidity of the color, Annie went to Henry Mowbray, who was then editor of the newly-founded Sandspur, and delivered a sales talk that apparently sold.” We do have a record of Miss Fuller, who attended the Rollins Academy in the 1890s.

Annie Fuller, a music student at Rollins, pictured with classmates and faculty in 1893. She is wearing a striped dress and is seated behind the young woman holding a guitar.

Annie Fuller, a music student at Rollins, pictured with classmates and faculty in 1893. She is wearing a striped dress and is seated behind the young woman holding a guitar.

Whether or not unrequited love played a role in the change, the College colors have been blue and gold since the student days of Sandspur editor Henry Mowbray–who also gave our student newspaper its name. But that’s another story.

~ by D. Moore, Archival Specialist