ROLLINS COLLEGE AND RACE IN THE ERA OF SEGREGATION, 1885-1954

PART I

by Jack C. Lane

Weddell Professor of American History, Emeritus

Rollins College

From the moment Rollins College opened its doors to incoming students in November 1885, its leaders faced a persistent dilemma: they had envisioned a northern school infused with New England Congregationalist liberal social values but they had located the college in a state and region dominated by a southern rural, conservative culture. For the most part, these two ways of seeing the world did not so much clash as they ignored each other, except in one area: race relations. By the 1880s, all southern states, including Florida, were beginning to establish a segregation system that relegated “colored people” to a position of second class citizenship. On the other hand, New England Congregationalists were steeped in a long tradition of championing African American causes beginning with the abolition of slavery and continuing, after emancipation, to demanding equal justice for freed slaves. For Rollins College, this cultural disconnect created a perpetual uneasy imbroglio.(1)

Let’s pause a moment to review the breadth and the depth of what became known as the Jim Crow system, a whole way of life based on a deep-seated belief in white supremacy, on the conviction that African Americans were incapable of responsible citizenship. By the time of the founding of Rollins College, Florida had followed other southern states in an effort to force freed slaves to the margins of white society. They began passing laws that separated the two races in all aspects of public life, including public transportation, restrooms, building entrances, elevators, cemeteries, amusement parks and cashier windows. Segregation laws established separate schools for black people and whites and some even required separate textbooks that were stored in separate depositories. Most towns and cities forced black people to live in segregated neighborhoods and forbade them to leave after sundown. By 1900, state laws made it impossible for black people to vote in any election and threatened their lives if they tried. All this legislation was supported by white public opinion and enforced by the local police departments as well as by extra-legal terrorist organizations like the KKK. Lynchings of black people, mostly for perceived or fabricated transgressions, occurred with regularity throughout all southern states. Any white person who resisted or opposed these laws and customs had to endure the opprobrium of the local community and was often ostracized.”(2)

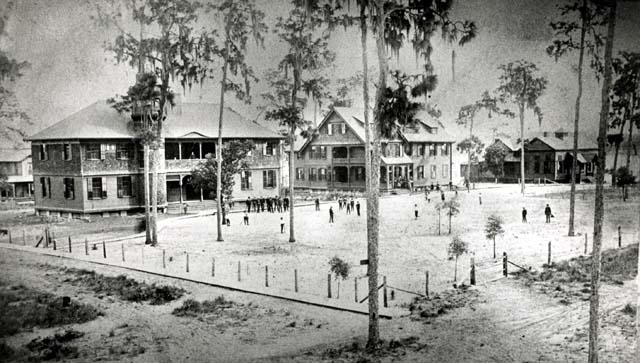

This was the social and political system in Florida when the Florida Congregational Association founded Rollins College in 1885. For decades devout Congregationalists governed the college, instilling New England Congregationalist social and educational values into all aspects of college life. The first four presidents were ordained Congregational ministers from New England. They all were schooled in Congregational social justice activism, including the denomination’s long tradition of championing African American causes.

With this kind of tradition and leadership, confrontation between the college and the entrenched local segregation system seemed inevitable. An internal altercation over race came early in the administration Charles G. Fairchild (1893-1895), Rollins’s second president. He was a graduate of Oberlin College, an institution with a fierce abolitionist tradition. When Fairchild was a student Oberlin was an active supporter of Radical Reconstruction. Moreover, he had experienced an integrated college because Oberlin had been admitting African American students since 1837. Not surprisingly then, shortly after he arrived at Rollins in 1893, Fairchild unequivocally revealed his views on race relations. He let it be known that if a Negro applied for admission he would judge him on his qualifications not the color of his skin. The statement produced an immediate backlash from the trustees. A struggling frontier college desperate for students, they told Fairchild, could not afford to disturb local customs that prohibited racial school integration. One trustee warned Fairchild that the college would lose all support, financial and otherwise, if the president enrolled a “colored” student. Not surprisingly Fairchild lasted only two years. (3)

Fairchild’s successors fared no better in the realm of racial relations. Unanticipated difficulties began in the administration of George Morgan Ward (1896-1902). Shortly after assuming office, President Ward received an inquiry from the American Military Government in Cuba asking the college to admit Cuban students from that war torn island. Always eager to increase the number of full paying students, Ward agreed. When his successor, William F. Blackman (1902-1915), arrived he found the number of Cuban students had risen to several dozen. By that time local residents noticed that some of the Cubans were a bit dark in skin color. The president soon began receiving letters from parents threatening to withdraw their children if the college continued to enroll “coloreds.” Blackman ultimately bowed to the pressure. In October 1906, he informed the island’s educational authorities that Rollins was forced to impose new restrictions on the kinds of Cuban students it could admit. “Public opinion is such in the South,” he explained, “that we cannot accept Cuban students if there is in them any admixture of colored blood and we will be obliged to send him away in case he were to come to us through any misunderstanding.” (4)

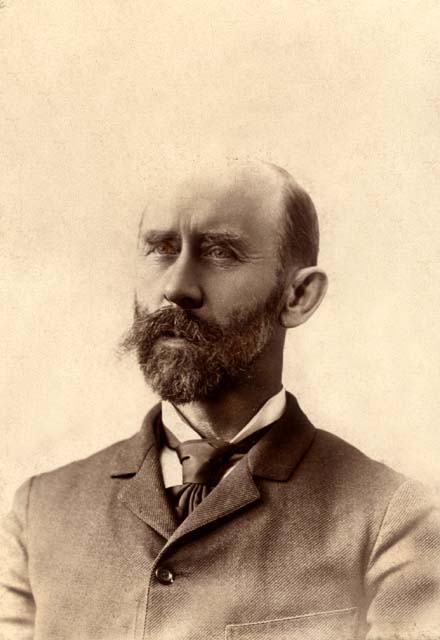

The need to write this letter must have vexed this mild mannered, tolerant graduate of Oberlin College. Yet his response to the Cuban issue established a familiar pattern. The reality that the college was embedded in a conservative community and encircled by an illiberal, racist region, led Rollins presidents and trustees to conclude that survival depended on conforming to the social mores of the segregation system, even though the requirements of that system warred against the college’s fundamental values. This dilemma continued well after the Blackman administration and no one experienced its effects and with more discomfort than the college’s eighth president, Hamilton Holt (1925-1949).

Holt’s kinsfolk had for decades established traditions of active involvement in seeking justice for African Americans and Holt often spoke proudly of that family heritage. His great-grandfather was Lewis Tappan, a leader in the antebellum abolitionist movement and an activist in the Underground Railroad. Tappan was also an early contributor to Oberlin College, which, Holt frequently noted, “made no distinction between race, sex, creed, or religion.” After graduating from Yale University in 1894, Holt went to work for his grandfather’s magazine, The Independent, which was a leading advocate of racial justice. There he met his future mentor, editor William Ward Hayes, who was using his editorial skills to champion African American civil liberties. Hayes wrote scathing articles opposing Jim Crow laws as well searing editorials condemning lynching. He often used language reminiscent of abolitionists: “We are learning that it is not well to make concessions to the caste of prejudice. The right way to fight against it is vigorously and persistently and never yield an inch.” Holt himself rarely wrote on race issues because, he said, “there were others on the staff who were more qualified to do so. But I believed the position of the magazine was right and still do.” (5)

Holt therefore saw himself as a contributor to those long family traditions of racial justice. He became involved in the founding of the NAACP and after assuming the editorship of The Independent, he continued to champion its causes. He knew W.E.B. Dubios personally and often published his articles in the Independent. He also established a close friendship with Booker T. Washington and spoke more than once at Washington’s annual conference at Tuskegee Institute In Alabama. Thus Holt brought with him to Rollins a national reputation as an advocate for African American equal rights and with a strong dislike of the segregation system, attributes completely at odds with white supremacy views of most Central Floridians.

Holt may have thought, with some justification, that Winter Park and Central Florida were really not “Southern,” that the decades long northeastern colonization of the area had created a condition more amenable to racial harmony. If so, he would have been sadly mistaken. The segregation system and the belief in white supremacy, frequently supported by the editor of the Orlando Sentinel was well entrenched in Central Florida. The city of Orlando and all surrounding towns had their segregated neighborhoods. The street dividing the white and black sections in Orlando loudly broadcast that separation—it was (is) called Division Street. Winter Park, the home of Rollins College, had a more traditional division. The founders of Winter Park created a section called Hannibal Square intended for African Americans who would serve as “help” for wealthy northern winter visitors. They placed it across the railroad tracks to separate it from the white development. Hannibal Square ultimately evolved into a throughly segregated part of Winter Park. (6)

The KKK was menacingly active throughout Central Florida when Holt arrived in 1925 and was constantly on the alert to violations of the segregation system mores. Not a small number of police officers were members, including many of the chiefs of police. Just prior to Holt’s arrival in Winter Park, a KKK-led mob rioted in Ocoee, a few miles from Orlando, murdering several African Americans and burning their homes to the ground. No one was ever arrested. Thus, when Hamilton Holt assumed the presidency of Rollins in 1925, he found a thriving KKK and a Jim Crow segregation system deeply entrenched throughout local life.(7)

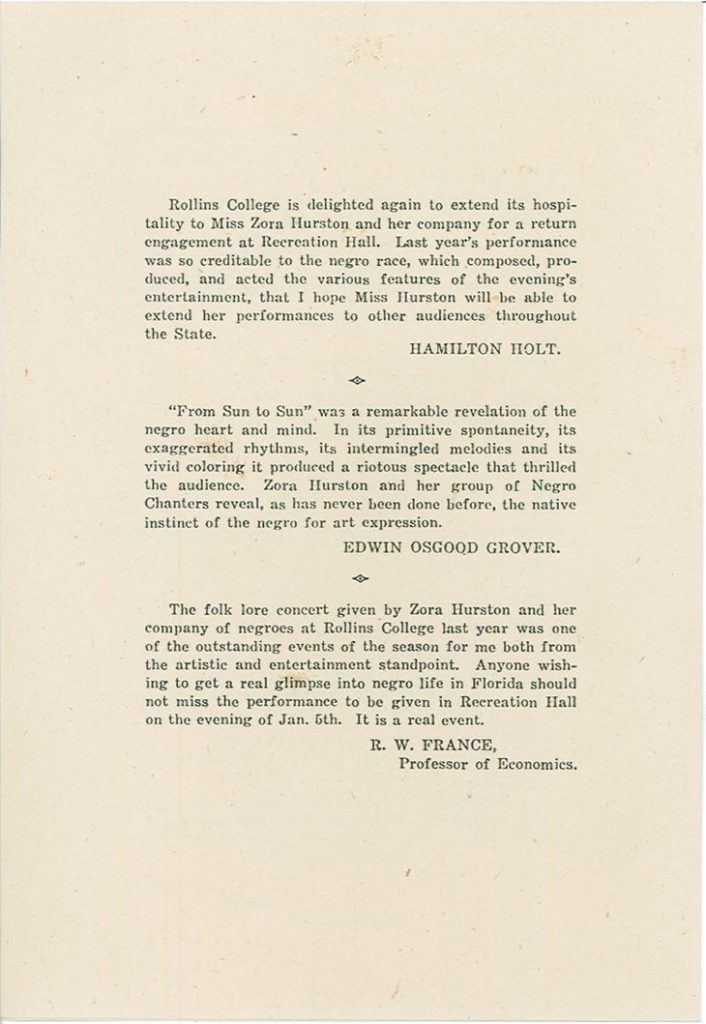

To complicate matters, under his leadership, Rollins became a leading progressive college with ideals and values even more seriously in conflict that the Jim Crow system. In addition, he hired professors who publicly showed their opposition to that network of discriminations. One was Professor of Books Edwin Osgood Grover, who worked quietly to mitigate its effects. Without fanfare, he worked tirelessly to improve the life of African Americans in Hannibal Square. He and his wife started a nursery for working mothers, created a children and adult library and in his later years helped establish a nursing home for elderly African Americans. For years he served on the board of trustees at Bethune-Cookman College. Grover was not publicly vocal in his opposition of the segregation system, but he showed a singular regard for the dignity of African Americans that the Jim Crow segregation system daily denied. Grover’s charity work in Hannibal Square elicited little reaction because white missionary-like work among African Americans was permissible under the segregationist code of behavior. (8)

Another early Holt faculty appointment was far more open, direct and confrontational. Professor Royal France, who came to Rollins in 1929, became the college’s most outspoken (and controversial) critic of Jim Crow. As he wrote in his autobiography: “being a college professor with liberal views [on race] in a community like Winter Park was not honey and roses, My refusal to adopt the mores of the South on racial questions brought me into to frequent conflict with local Southerners.” In October 1934, France learned that a mob was threatening to lynch a black man in Marianna, Florida. France was out of town at the time, so he asked President Holt to intervene. Holt tried to contact Florida Governor David Sholtz but was told that the governor was our of town and could not be reached. On October 19, the mob brutally lynched Claude Neal. France immediately wrote a “blistering letter” to the Florida governor demanding to “know what more pressing matter he had had in Florida that night than to see that the law was enforced.” France sent the letter to several newspapers around the state and it was widely distributed. The following day, Sholtz called Holt demanding the president fire France for insulting a Florida governor. Holt told Sholtz he wouldn’t do that since he agreed with France.(9)

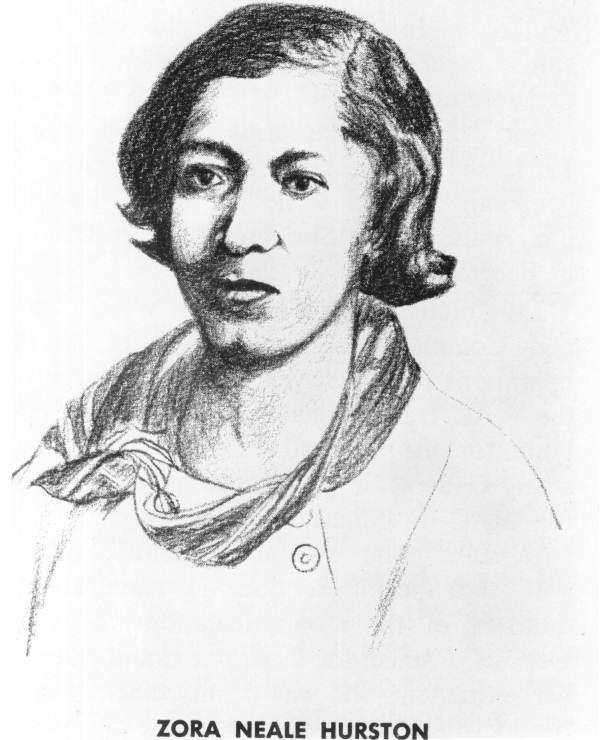

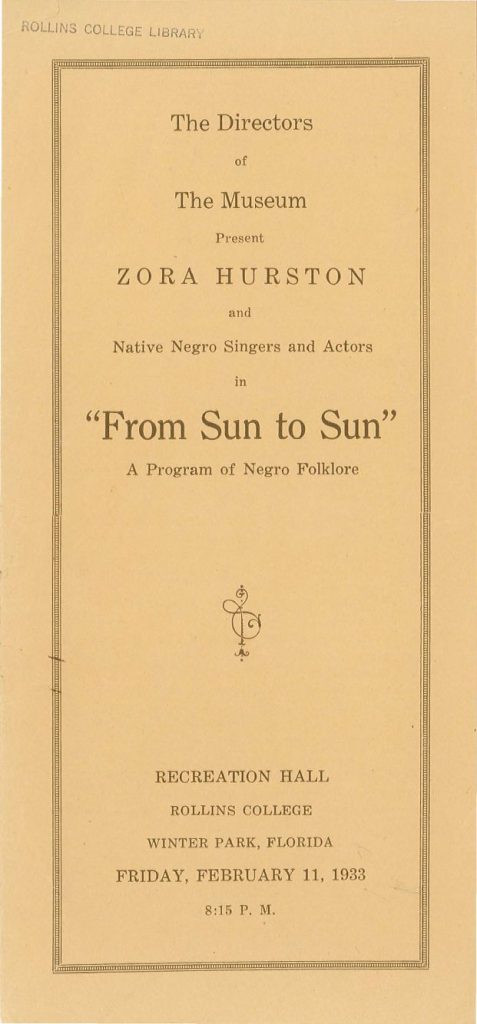

France’s friendship with a promising young African American playwright named Zora Neale Hurston, who lived in New York but whose home was in nearby Eatonville, drew the most criticism from local residents. At some point during a production of her play at Rollins (see below), Hurston became acquainted with Royal France and his wife Ethel. When visiting her home in Eatonville, Hurston frequently stopped by to see the Frances. During one visit on a rainy afternoon they became engrossed in conversation, until late in the evening so “with no thought of the racial barriers, Ethel invited her to stay.” According to France, while they were dining, a Rollins faculty member, who was “a dyed-in-the-wool Southerner,” showed up at their doorway and “when he saw the family at the table with a Negro, his disgust was so great it was almost tangible.” When it became known throughout the town that Hurston had spent the night, France and his family became “pariahs in Winter Park,” often shunned in public places and in retail stores. It was if they “had committed the sin of sins and had to be punished.” He was subject to “attacks and sometimes to anonymous threats of personal violence.” On one occasion someone called him one evening telling him that a mob was going to lynch a black man outside of town. He checked with police and found that no such incident was happening. France believed they were trying to lure him out of his house in order to attack him. Criticism of France’s behavior often reached the president’s desk but to Holt’s credit he always brushed it aside. In fact, before he retired, Holt awarded France an honorary degree, citing his important role as political and social activist.(10)

It was Zora Hurston herself who created a situation that for the first time forced Holt to grapple specifically with what he called the local “Negro problem.” Hurston initially became associated with the college when she met Professor Osgood Grover in the spring of 1932 and told him about one of her folk plays. Grover put her in touch with Rollins theatre director Robert Wunsch, who at the time was searching for folk plays that would allow Rollins students, in his words, to experience “the honest-to-the-soil material at their own doorstep.” Wunsch agreed to produce the play on the Rollins campus before a racially mixed audience—if the president agreed to the arrangement. One obvious venue for the play would have been Holt’s pride and joy, the new constructed Annie Russel Theatre. All this presented Holt with a well-worn dilemma—approve the proposal and accept potential repercussions from local segregationists or capitulate to local mores and deny the request. Holt compromised. “I see no reason.” Holt wrote Wunsch, “why you should not put on in the recreation hall a negro folk evening under the inspiration of Zora Hurston. Of course we cannot have negroes in the audience unless there is a separate place segregated for them and I think that would be unwise.” Holt rejected the Annie Russel venue and cautioned Wunsch not to advertise outside the campus, apparently so as not to alert the local community. Hurston and Wunsch accepted Holt’s conditions (they could hardly have done otherwise). The play was a huge success with an audience of students and faculty and a scattering of locals. Moreover, the production proved to be the beginning of Hurston’s close associations with Grover and Wunsch, both of whom helped restart her declining literary career. (11)

Let us pause (again) before leaving this hopeful ending and dig a little deeper into Holt’s decision to permit the performance only if viewed by an all-white audience. There is a subtext lurking here just below the surface, an underlying thread that runs from the era of slavery, through the Jim Crow period to the present today. White Americans have a long history of seeking entertainment by black performers in a setting that allowed them to retain their sense of superiority. Slave owners often commanded slaves to perform for friends and family in ways that forced them to behave in silly and witless ways. What may be called the “white gaze” of African American performances can be seen as an expression of white supremacy in the sense that the gaze reinforced white people’s perception that African Americans were innately clownish and infantile. By the post Civil War Jim Crow era (Jim Crow itself being a cartoonish view of black behavior) the convoluted, complex mores of the segregated system permitted all-whites audiences to watch African Americans perform on stages in often degrading ways—sometimes referred to as “shuck-and-jive”—with the expectation that the performers would deepen their stereotypical white view of African Americans. Whites could actually relish what they saw as exotic African American performances while at the same time maintaining a sense of distance and superiority. Mixed audiences were forbidden in the South unless black people were appropriately separated from the white audience, which was another way of expressing white supremacy. (12)

Holt’s acquiescence to the production of Hurston’s folk play on the Rollins campus with a white only audience was a low risk decision because it was well within the historic parameters of local segregation customs. However, Holt’s conditional approval seriously diminished the impact Hurston desired. She had written a serious play that elevated African American folklore above earlier vaudevillian minstrel-like performances that often perpetuated black stereotypes. She was also looking for a venue which would allow local African Americans to experience their folk culture performed in a serious, rather than in a demeaning manner and where white audiences could encounter African American reactions to their folk world. Progressive Rollins with an open-minded president seemed an obvious choice but she found that liberal President Holt was unwilling to cross the “color line.” (13)

Moreover, Holt’s demand for a white only audience meant that only whites would be left to interpret the play. Most reviews were laudatory but the language reveals that even those who raved about the play could not avoid (most likely unintentionally) stereotyping African American behavior. A commentary in a Winter Park newspaper observed that the audience saw something strangely outside the realm of white experience, as if the players had come from another country rather than just a few miles away from the campus. The play, the reviewer noted, gave the white audience a “sense of native (meaning primitive) rhythm and harmony which is hard to comprehend unless seen and felt.” The negroes “brought barbaric color to Nordic restraint.” The Rollins student newspaper, the Sandspur, spoke of the primitive “seductive” dance pieces suggesting an orgy. What would have seemed perfectly comprehensible to African Americans, had they been able to see the play, for the white audience seemed exotically foreign. One unimpressed critic was more blunt but probably expressed an attitude more in tune with local white convictions. He dismissed Hurston’s attempt to give dignity and meaning to African American folklore. The play, he charged, wasn’t even authentic. For this critic, the “real” negro was the one depicted by white musician Jimmie Rodgers, one of whose “Blue Yodel” songs was about a “lazy, indolent negro telling his troubles to the world.”(14)

However risk-neutral was Holt’s compromise on Hurston play, the fact remains he did permit a theatrical work with Black actors to be produced on campus and thus had not completely capitulated to local racial prejudices as had his predecessors. The same could not be said about subsequent racial issues Holt was forced to deal with. Around the time of the Hurston’s play was in production, Holt received a request from a sociology professor teaching at the all black Bethune Cookman College in Daytona. He told the president of his interest in the Rollins Conference Plan of teaching and that he would like permission to bring his students to one of the classes to learn first-hand about the new pedagogy. Ordinarily, nothing could have thrilled Holt more than to show off his crowning academic achievement. But it was not to be because Holt again refused to cross the color line. Several years later he described his thinking at the time:

All my principles and inclinations were to let him come. I was confident that the majority of the faculty and trustees would approve. But I saw there was a real possibility of some parents taking the daughters or sons out of Rollins if this was permitted and that might lead to an incident which might end in some form of violence and do permanent harm to Rollins. I was in great distress as tp what was the right thing to do but I finally decided it this way. I said to myself: “What did I come here for; to solve the race problem or to help build up Rollins?” The answer was inevitable….I did not invite the professor and his class to come [even though] it was a violation of my whole general attitude on the race question. If I had come down here to make the chief concern of my life solution of the Negro problem, then I would have put the race issue above the welfare of Rollins.(15)

Holt’s reasoning in this particularly incident was characteristic of his approach to the friction between the college’s liberal social justice principles and the discrimination inherent in the local segregation system. A portion of Holt’s thinking mirrored previous presidents contentions that survival depended on strictly adhering to the conventions laid down by the local segregation system. As we have seen, some presidents actually received tangible evidence of what was required as when parents wrote President Blackman that they would withdraw their children if the college continued accepting dark skinned Cubans. From that point, Blackman’s successors assumed all white parents would make similar demands and thus threaten the college’s very survival. These assumptions meant that concrete threats were not required to create a sense of danger. Perceived and even imagined threats were enough to cause panic. Consider Holt’s phrase “might lead to an incident which might end in some form of violence.” In the Bethune Cookman case (as well as with iHurston’s play), Holt saw the threat as projected, as potential, possible but not unmistakable. Had it become known to the local area a professor from a black college was bringing his class to observe at Rollins, that would undoubtedly have caused a stir and some controversy. But it does seems a bit dramatic to argue that black students observing classes at all white Rollins would “cause violence and do permanent harm to Rollins.” After all, the Bethune Cookman students would be observing, not formally attending a Rollins professor’s class (probably Professor Edwin Clark’s). To satisfy potentially disgruntled local citizens, Holt could have (but did not) argue that the class visit was service to an all-black college, service on the same level as Osgood Grover’s charitable work in Hannibal Square.

When Holt said he agonized over the “right” thing to do did he mean “right” in the principled moral sense or “right” as prudently expedient? As it turned out, it seemed to be the latter. All this mattered because the college’s behavior on race met the exact definition of hypocrisy: “the practice of claiming to have moral standards or beliefs to which one’s own behavior does not conform.” Sooner or later an incident was bound to publicly reveal this pretense and thereby raise serious doubts about the college’s commitment to its stated principles and values. That incident occurred as Holt neared the end of his tenure as president.

Endnotes

1. On the details of the founding of Rollins College, see Chapter 1 in Jack C. Lane, Rollins College Centennial History: Story of Perseverance. Story Farm, 2017

2. One southern writer described white attitudes toward “coloreds” with brutally frankness: “The negro is the mongrel of civilization. He has married its vices and he is incapable of imitating its virtue. He has exchanged comparative chastity for brutal lust. His religion is merely an emotional impulse. He is a spiritual hypocrite.” Corra Harris, “A Southern Woman’s View,” Independent, May, 19, 1899, 1354-1356.) The classic and still the best study of the origins and evolution of the Southern segregation system is C.Vann Woodward, The Strange Career of Jim Crow.1955.

3. Rollins College, Centennial History, 72-73.

4, Ibid.,106-107. “Admixture” in Jim Crow Florida meant that if a person had “one-sixteenth or more “ of Negro blood he or she was considered “colored.”

5. Holt quote in “Hamilton Holt Speech at Bethune Cookman College, March 17. 1950. Ward quotation in Jack C. Lane “The Complicity of Silence: Race and the Hamilton Holt/Corra Harris Friendship, 1899-1935.” The Independent, April 23, 2015.

For a biography of Holt’s life see Warren F. Kuehl, Hamilton Holt: Journalist, Internationalist, Educator. Gainesville, FL: University of Florida Press, 1960; My essay on the Holt/Harris friendship describes one part of Holt’s life that seems curiously at odds with the above description of his beliefs and behaviors toward race. While he was managing editor of the Independent Magazine he came across an essay by an unknown writer named Corra Harris from Georgia. In the article she passionately defended lynching as an appropriate way to deal with the perceived threat posed by African Americans. Holt published her article and several more, all severely critical of African Americans. Out of this acquaintance came a friendship that lasted several decades despite Harris’s unabashed deep-seated racism. At his presidential inauguration, HoIt award her an honorary degree and she later taught a course at Rollins on the nature of evil. She is quoted in the body of the essay at Endnote #2.

6. Julian Chambliss, “Hannibal Square: The Evolution of a Dream: A Community Presentation.” Presentation, April 23, 2016)

7 .David Chalmers, “The Ku Klux Klan in the Sunshine State: The1920s,” Florida Historical Quarterly. Vol 42. (Jan., 1964), 109-217.)

8.Wenxian Zhang, “Edwin O. Grover: Professor of Books and Citizen of the Community,” Rollins Archives.

Throughout the later Holt years and in the decade afterward, Rollins students, in the “good works” tradition of Osgood Grover, continued to be involved in Hannibal Square neighborhood primarily through the Interfaith and Race Relations Committee. One of the committee’s most active academic years was 1950-1951 when Rollins’s acclaimed graduate, Fred Rogers, was the chairman. During the year the committee’s efforts, according to Wenxian Zhang, “included collecting and sorting books for the Eatonville community, raising funds for the future DePugh Nursing Home for African Americans, working with a local electric company to have fluorescent lighting installed at the Hannibal Square Library in the west side of Winter Park, wrapping Christmas presents for needy families, attending a cultural programs.”

As with Grover’s efforts, the committee’s activities created little opposition in the local community because it was all within acceptable behavior of the segregation system. One writer has called it the “accommodationist” approach, wherein white, privileged young people could safely provide social services to the underserved African American community rather than causing friction by confronting the racial discrimination that was the reason aid was needed.

9 Royal France, My Native Grounds, 74-75. Also see Jack C. Lane, “Introduction” to Frances autobiography posted on Rollins College Scholarship.

The murder of Claude Neal by a mob in Mariana Florida was one of the most gruesome lynchings in this nation’s history. The incident created a national outrage that led to a concerted effort to make lynching a federal crime. Southern senators prevented the bill’s passage. James McGovern, The Anatomy of a Lynching: The Killing of Claude Neal. 1992.

10. .France, My Native Grounds, 75.

11.Maurice O’Sullivan and Jack C.Lane, “Zora at Rollins.” in Zora in Florida, eds. Steve Glassman and Katheryn Seidel, 130-145.

12.George Yancey, Black Bodies, White Gaze: The Continuing Significance of Race in America. 2009.

Minstrelsy and its progeny, blackface, have a very complicated history but generally both tended to reduce black people to well-defined stereotypical, demeaning roles.

13. The color line was a phrase made popular by W.E.B. Dubois. He used it to describe the invisible but well defined boundary between whites and black people, a line crossed at one’s own peril. In 1938 a Rollins student crossed that line and was arrested and jailed. See Jack C Lane “The Case of the Embryo Artist” and Vagracy Laws in Segregated Orlando.” eFHQ, Vol 1 2021.

14, Cited in O’Sullivan and Lane, “Zora at Rollins.”

15. Hamilton Holt, “Address At Bethune Cookman Convocation,” March 16. 1950.1

Zora Neale Hurston Photo: https://www.floridamemory.com/items/show/26609