ROLLINS COLLEGE AND RACE IN THE ERA OF SEGREGATION, 1885-1954

by Jack C. Lane

Weddell Professor of American History, Emeritus

Rollins College

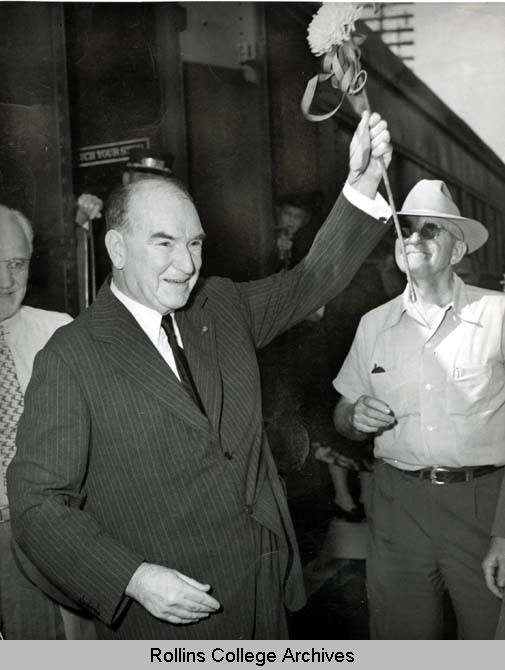

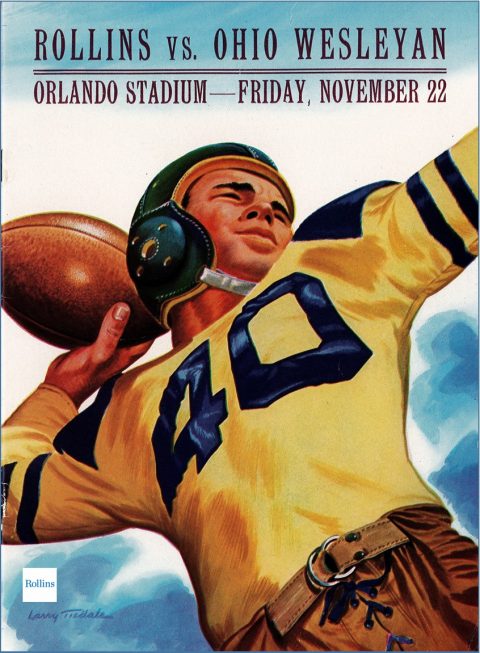

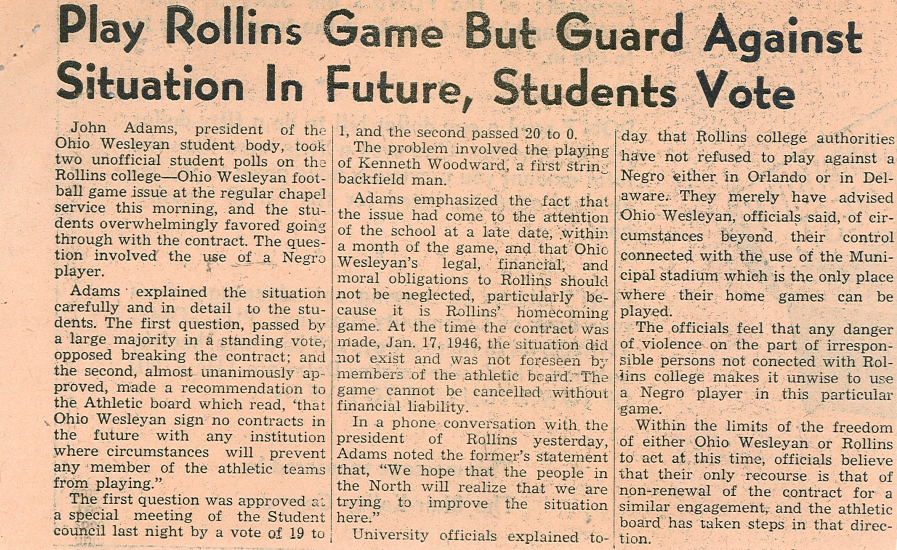

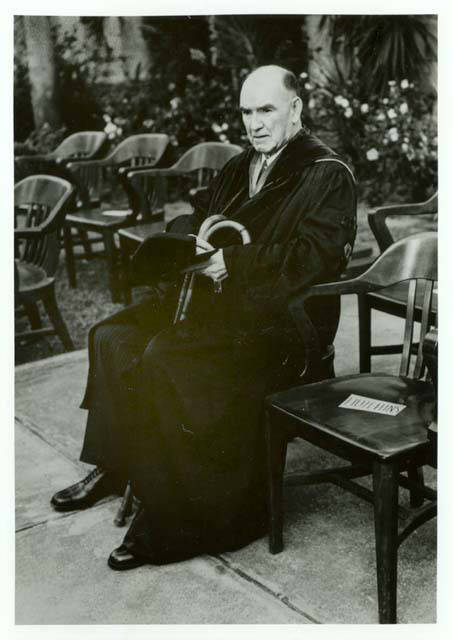

When the new school year began in 1947, President Hamilton Holt must have realized that his time as president was nearing its end. He had served for over twenty years, had guided the college successfully through the tumultuous years of the Great Depression and World War II. During that period, he had reconfigured the campus architectural landscape and transformed Rollins into a nationally recognized progressive, innovative institution. When he returned from New England for the 1947-1948 academic year, he found the college community more affectionate toward him than at any time in his presidency. But that good will rapidly dissipated when the Holt cancelled a football game between Rollins College and Ohio Wesleyan University. The reason for he cancellation: one of the players on the Ohio Wesleyan team was African American [Note to reader: Many details of the origins and development of the cancellation have been sufficiently covered in other essays, so in this piece I will include only those details necessary analysis. See: Endnote 1)

It was not the first time Holt faced a decision on race but this one proved to be a defining moment for the Rollins College. The Hurston play fell within segregationist conventions and the Bethune Cookman academic class incident remained quietly internal. But the cancellation of the football game received wide-spread public notice and thus threw a bright light on the dichotomy between the college’s professed beliefs about racial justice and its actual behavior. Moreover, the administration’s arguments for cancellation were based on rumors (one of Holt’s phrases was: “If rumors can be believed”) and unverified threats. As Dean of the College Arthur Enyart wrote the Ohio Wesleyan administration: “There might be [my emphasis] serious danger arising out of the situation [from] some die-hard “cracker” from the outlying districts…” The college lawyer told Dean Enyart Florida law forbid mixed participation in any educational function but Enyart was dubious as to “whether this law would stand up in our case…which I doubt and it need not here be considered. A more serious situation confronts us in public sentiment,” continued Enyart, and then he provided a whole list of the incidents that could happen ranging from racial slurs to a race riot to people getting hurt or even killed. Thus the administration constructed a worse case scenario based upon rumor and perceived dangers as justification for its decision to cancel. (1)

Holt must have sensed a growing discontent within the Rollins family concerning these rationalizations (or his own uneasiness with them) because immediately after the cancellation decision he gathered the faculty and students in Annie Russell Theatre so that, according to the Sandspur, he could “reveal the facts behind the cancellation and the reasons which impelled the board of trustees to act as they did.“ The president’s presentation, however, had the feel of an apologia or perhaps even a cri de coeur. In the end, it was a futile attempt to defend the indefensible. In the speech, Holt first tried to place the “race issue” in context. Historically, he said, the race issue has been “the most insoluble of all for it is founded not on reason or logic but prejudices, fears, suspicions-in fine emotions.” Holt followed this disquisition by reassuring every one of his own bona fides regarding race. “It must be obvious to you that by inheritance and whatever reasoning and ethical powers I posses I believe that a man should be judged as individual…and not by the race of which he is a member or the color of his skin.” Then he posed a question everyone must have been pondering: Given his “inheritance” and his own beliefs about race, why wasn’t he on “the firing line in this perplexing issue that has [often] confronted Rollins? Holt then attempted to provide an answer to that puzzling question:

After debating the long run versus the short run, it was perfectly obvious to us all as [the trustees] discussed this point, that Rollins, living in the Deep South as we do, was forced to risk misunderstanding and criticism in the North in order to take what we believed would be the better course to better relations between the white and black people in the South. If Rollins persisted in playing with [“a colored boy”] and taking the consequences we might lose—probably would lose—the good opinion of a certain section of the community. But even more important than these considerations is the fact that if we defied public opinion in any open way in the Deep South. It would precipitate a race crisis and when the crisis was over, no matter which way its was settled, it could not have materially hastened the coming of better relations between the races, but would more likely set them back—perhaps a long time. The loyalties Rollins and its ideal were not to precipitated a crisis that would promote bad race relations but to work quietly for better race relations, hoping and believing that time would be on our side. “(2) Similar reasoning and justifications had been used for generations, but, for reasons cited above, by the 1940s such rationalizations no longer sufficed because they left a large chasm between Holt’s oft-used expression of “Rollins Ideals” (and all that entailed) and the college’s behavior when those ideals were threatened. This schism could no longer be explained away by platitudes. Moreover, the incident was now in the glare of public view. It was being reported by both local and national news sources with such headlines as “Jim Crow Wins” at Rollins College. This situation led several members of the college community to remind the college of moral lapses in the president’s “explanations.” Professor of English Nathan Starr, supported by several other faculty members, sent a letter to the Sandspur where he warned against “heeding the voice of anti-liberal opinion in the community under the fear of violence (which in my opinion would not have materialized), Rollins has placed itself in a very compromising and constricting position. It is a heavy price to pay.” In an effort to create a more a specific policy on racial issues, Professor of Economics Royal France introduced a resolution at a faculty meeting that would have made clear the college’s position on racial justice. The resolution called for a set of principles that would guide the college when future racial issues arose. His motion failed to gather a majority faculty support. (3) Thus, the administration and the majority of the faculty seemed ready to consider the racial incident closed, but several students refused to let the matter rest. They firmly stepped in to instruct the college community on its moral responsibilities. Two students sent the president open letters, both published in the December 4, 1947 issue of the Sandspur, taking umbrage with Holt’s explanations for cancelling the game. One student placed the incident in a larger context: “In times like these when hate rides high and intolerance plagues the world, no institution of [higher] learning should compromise with any act contrary to the American Way.” (4) In a second open letter a student restated the college’s own published statement principles and then posed a question: When Rollins College says it “exists for the purpose perpetuating and advancing culture.” the student asked, “Is Rollins advancing culture by acquiescing to racial discrimination?” When Rollins says it is a democratic society that leads “its citizens to develop the means for making mature judgements.,” the student response was “Does an act of intolerance qualify Rollins to teach others to make mature judgements?” (5)

It was, however, a candid student editorial, written with great clarity, that cast the brightest light on how cancelling the game left serious doubt about the college’s claim that it stood for a moral liberal education. The editorial deserves to be quoted fully:

The time is past for discussing how right or wrong was the decision made by the trustees regarding the Ohio Wesleyan game; but it is not too late to discuss the fundamental issues that are raised by the decision. It is a time for facing squarely some disturbing moral questions. One of the main arguments on which the trustees based their decision is that a football game is a community affair.’ And so it is, to the extent that any such game is largely supported by members of the community. But it seems ridiculous that basic college policies, even about football, should be dictated by the community. After all, a college should be a center not only of learning but of leadership. Its members should be defenders of liberal action rather than mere followers of community reactionaries. To allow important policies to be determined by our environment is to sink into ineffectual romanticism and to avoid our intellectual responsibilities. And we must face those responsibilities, or face the fact that we can no longer call ourselves a liberal college.

But an even more pressing question raised by the whole affair is that of compromise. How much should we compromise; how far should we carry our principles? The decision made with regard to this game might well be construed as implying that compromise is to be preferred at all costs to overt action in a situation of this sort. Possibly this is true, in this particular case. But it is dangerous as a general thesis—for it is much easier to relax and avoid one issue after another than to decide on an action which may involve general unpleasantness or personal danger….We must not be blinded by the possibility of violence to the larger possibilities for good in a given situation. We must not sink into existence of “quiet desperation” and forget when to stop compromising. It is a dangerous thing to forget.

If this issue actually boils down to a fundamental conflict between idealism and realism, it is all too easy to see where the college stands. Our liberal principles, our high ideals…it becomes apparent that such visionary concepts must, at the first conflict, be sacrificed to expediency. Have we forgotten that ideals, to be worth anything, must be lived by and fought for; that they are worse than useless if the first clash shows them subservient to pragmatic realism? This is a center of higher education and for such a mistaken attitude we have not even the excuse of ignorance.(6)

In three paragraphs this student editorialist exposed the uncomfortable truths concerning not just the problem with the administration’s cancellation of the football game, but also the college’s standard approach to racial issues over the previous five decades. All those past administrations proudly promoted Rollins as a college guided by the noble ideals of a liberal education. Thus, when the administration, in the student editorialist’s phrase, sacrificed those ideals to the expediency of not disturbing the status quo, the college was particularly vulnerable to the charge of undisguised hypocrisy.

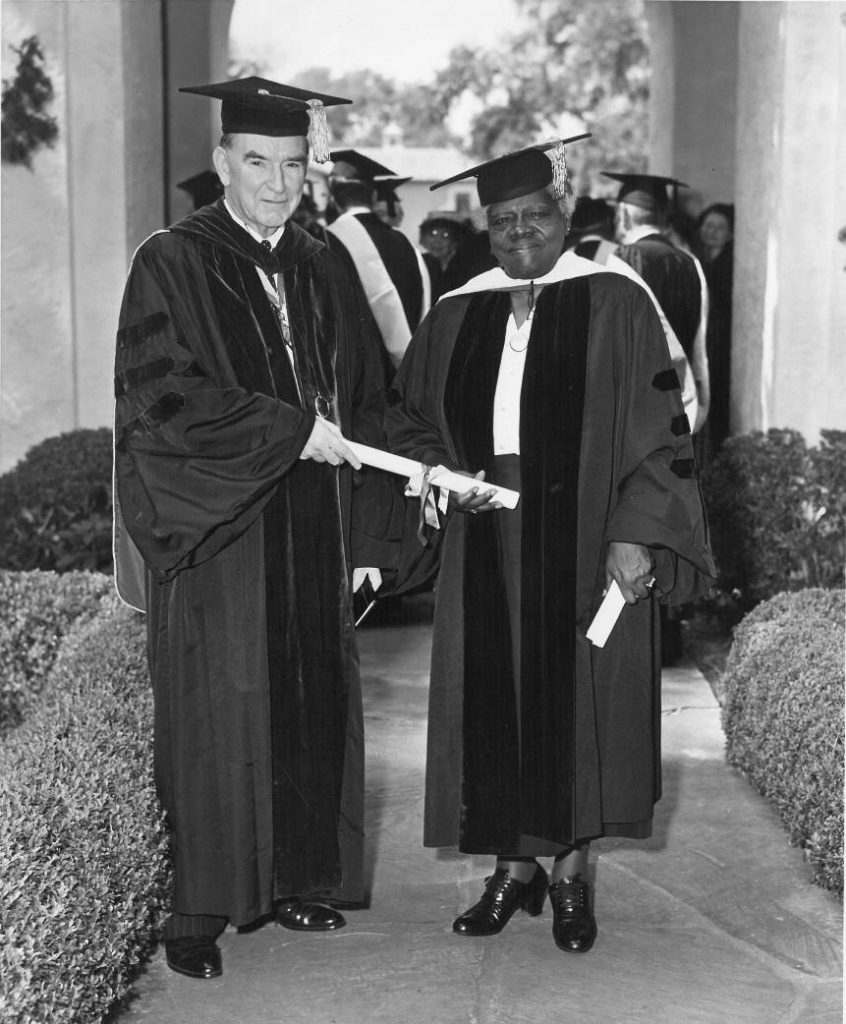

Holt later declared that the decision to cancel the game was completely contrary to his own liberal progressive inclinations and it left him humiliated and remorseful. “It was a sickening decision for me to make” he wrote a friend, “and it is quite possible that if we had gone ahead nothing would have happened.” He spent weeks apparently worrying about whether he had made the right or wrong decision, admitting at one time that he had probably made a mistake. He therefore began searching for a way to repair the damage or at least salve his own conscience. A few months after the Ohio Wesleyan incident, at the 1947 commencement, Holt awarded the Decoration of Honor to Susan Wesley, an African American woman who had served as a college housemaid at Cloverleaf dormitory for twenty-five years. The award was well deserved and was a thoughtful gesture on the part of the president but it was an internal award and Holt needed something more dramatic to widely broadcast that Rollins had the courage of its moral convictions. Holt thus decided to recognize the accomplishments of his good friend and colleague Mary Mcleod Bethune, president of Bethune Cookman College, the all-Black institution in Daytona.

By the 1940s, Mary Bethune had achieved recognition as one of the nation’s foremost female African American leaders. Her activism on behalf of African Americans was legendary, particularly in her opposition to Jim Crow. A champion of racial and gender equality, Bethune founded several women’s organizations and led voter registration drives, often enduring racial attacks, after women gained the vote in 1920.

Holt apparently made her acquaintance when he was involved with the NAACP and their friendship strengthen when Holt became president of Rollins. In 1931, at Holt’s invitation, Bethune delivered a speech in the Rollins chapel then located on the second floor of Knowles II Hall. Before a “large group of students she held spellbound,” Bethune proclaimed her opposition to “discrimination and segregation any kind.” After all, she continued, “the negro can no more help being a negro than you can being white. Let us turn the searchlight within and see what shall be done…There can be no divided democracy, no class government, no half-free county, under the constitution. Therefore, there can be no discrimination, no segregation, no separation of some citizens from the rights which belong to all. We must claim full equality in education, in the franchise, in economic opportunity, and full equality in the abundance of life” (7)

The two presidents continued their relationship in the years following her speech in 1931. For Holt, in both personal and professional terms, Mary Bethune was a perfect candidate for an award that, would, he hoped, plainly show Rollins as a college of racial tolerance. Holt’s invitation in December 1948 read as follows:

December 22, 1948

Dear Mrs. Bethune,

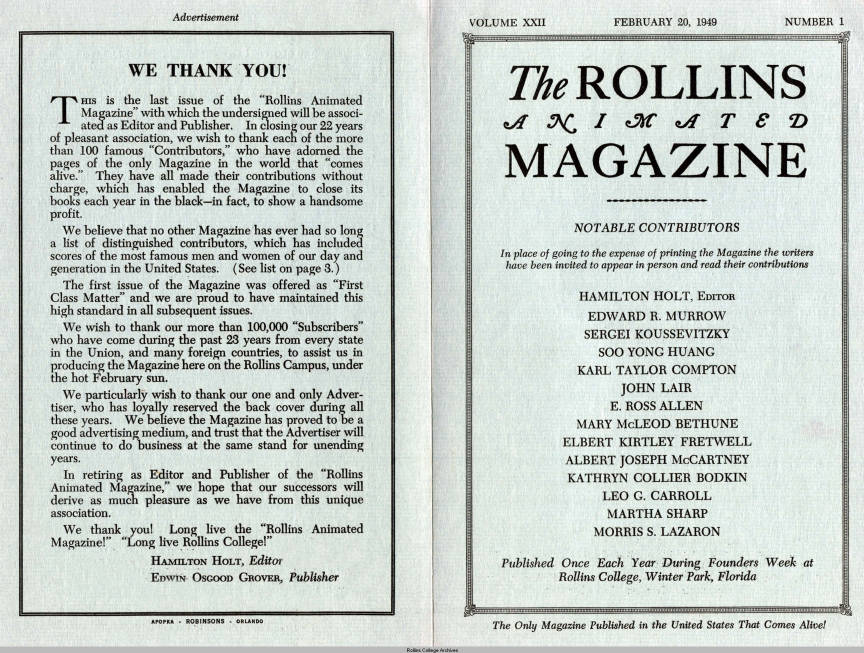

At a meeting of the Committee on Honorary Degrees just held I am authorized to invited you to be present on Friday morning, February 21, in Knowles Memorial Chapel and receive the honorary degree of Doctor of Humanities (LHD) I am very glad to invite you to be my guest at luncheon at one o’clock at my home on Sunday, the 20th, with the recipients of honorary degrees and those contributors of the so-called “Animated Magazine,” which is “published” on he campus at two-thirty immediately after the luncheon. There will be a dozen or more men and women of national reputation who will appear in person and read from their own writing or speeches, something from five minutes in length and I invite you to be among these contributors.

If you accept this invitation, as I sincerely hope you do, please keep this invitation in confidence until the day that the degrees are conferred, in accordance with academic custom.

Fraternally and Faithfully yours

[Signed, Hamilton Holt]

A few days later Bethune replied:

My dear Mr. Holt,

May I express my sincere gratitude for your gracious letter of December 22?

It is with a sense of pride, honor and deep humility that I accept your invitation to be with you on Monday Morning, February 21, 1949, to receive from historic Rollins College the Honorary Degree of Doctor of Humanities.

May I thank you also for you invitation to luncheon at you home on Sunday, February 20, at 1 o’clock. It will be a privilege to have this hour with you, the contributors to the Animated Magazine and the others who are to receive honorary degrees. I have followed, for many years, the unique presentation of the “Animated Magazine” on your campus. I accept, with enthusiasm, your invitation to make a contribution to the magazine . For

me, this is a dream come true.

Sincerely yours, Mary Bethune (8)

Given the racial situation in Central Florida in the late 1940s, an invitation to an African American woman to speak at such a public event as the Animated Magazine, then later to be awarded a honorary degree at all-college convocation, required no small amount of “valor.” As noted above, the Jim Crow system was still flourishing in Florida in 1949 and violence against African Americans continued unabated. In July of that year, the so-called Groveland Four were falsely accused of raping a seventeen year old white girl a few miles from Orlando. A mob killed one and the others were arrested, tried and convicted by an all-white jury. The Orlando Sentinel lent credibility to the arrests by printing on the front-page a drawing of four empty electric chairs under the headline, “No Compromise!.” Two years later, Lake County Sheriff Willis McCall gunned down two of the falsely accused men on an isolated stretch of road while he was transporting them from Raiford Prison to the Tavares courthouse. (9)

Yet, sitting there on the Animated Magazine stage constructed on Sandspur Field, on a sunny February morning, before a mostly all white audience of several hundred, sat President Mary McLeod Bethune among several distinguished white men (one was Edward R. Murrow). She spoke that day on the topic of Mahatma Gandhi, highlighting his non-violent confrontation against injustice. Gandhi, she proclaimed, was a “clarion call for minorities[telling them] that they have a power in them that they can learn to release, which transcends hate and greed.” (10)

The following day, in Knowles Memorial Chapel, she was awarded a degree of Doctor of Humanities. As Holt broadcast widely, she was the first African American to receive an honorary degree from an institution of higher learning in the South. In his presentation President Holt lauded her many accomplishments:

Mary McLeod Bethune,

I deem it one of the highest privileges that has come to me as President of Rollins College to do honor to you this morning. I am proud that Rollins, I am told, the first white college in the South to bestow an honorary degree on your race.

You have in your own person again demonstrated that from the humblest beginnings and through the most adverse circumstances it is still possible for one who has the will, the intelligence, the courage and the never-failing faith in God and in your fellowman to rise from the humblest cabin in the land to a place of honor and influence among the world’s eminent. In paying honor to you we show again our own faith in the land which made your career a reality. (11)

By all accounts, Bethune regarded the Rollins honor, from a man she admired and from a college she respected, as one of the most important moments in her professional life. She made certain the “Negro Press” was present at the event, one she claimed broke “all precedent in the South.” She wrote Holt that in her judgement to have the honor degree bestowed “in my own state gives me a humility that I cannot quite express.” The “entire Negro race [is] grateful to Rollins College…Your generous consideration was not given to Mary McLeod Bethune, but to the group she represents.” Holt wrote her that he had “received telegrams and letters of congratulations in regard to awarding you the honorary degree and I hope it will do some good along the line.” (12)

In a speech delivered at Bethune Cookman College after he retired, Holt told the audience that he had given honorary degrees “to Presidents of the United States, members of the Supreme Court, the Senate, the House of Representatives, the Cabinet and such men and women of national and international distinction as Thomas Edison, Jane Addams, Rabbi Wise, Greer Garson and many, many others. But none has given me more pride and satisfaction than the degree of Doctor of Humanities I had the honor of conferring a year ago on Mary McLeod Bethune.”(13) Undoubtedly, a large measure of Holt’s “pride and satisfaction” came from his sense (or hope) that the award resuscitated his and the college’s reputation so seriously damaged by the Ohio Wesleyan debacle. Whether or not that hope would come to fruition depended on how future presidents responded to the “Negro Problem.”

Assessment

How do we assess the almost seventy years of the college’s consistently ambivalent responses to the racial challenge it confronted during the era of segregation? One way is to view Hamilton Holt as not only as the inheritor of past presidential decisions on race, but also as one who was tested more often than the others during a period of dynamic change. Because he had frequently and publicly professed his personal opposition to the Jim Crow system and because the identity of the college changed significantly during his long presidency (over 20 years), more than previous presidents Holt sensed a special obligation to articulate the reasons guiding his decisions regarding race. In one sense, he followed his predecessors’s policies. He often, with good evidence, used Rollins’s location as a reason for inaction toward race—“public opinion in the South is such,” was Holt’s phrase. But Holt went much further in his apology for inaction. More than once he talked about a binary dilemma of loyalty to the college vs the responsibility to help solve the “Negro problem.” In a personal statement, he asked, somewhat meditatively, whether he had come to Rollins to facilitate social change or to help make Rollins a better college. Given that binary choice, he told one audience, his decision was “inevitable,” that is, that the welfare of the college came first. But this reasoning is misleading on several levels. Holt’s decision about racial issues discussed above waa all about Rollins’s values versus the local segregation system. However much those values jarred agains segregation, any push back from the college would have had little influence on the larger, so-called Negro problem. More importantly, it could be and was argued that confronting rather than ignoring racial discrimination would make Rollins a “better college,” able to loudly proclaim its adherence to its stated values. Little wonder students and faculty left the Annie Russell meeting a bit perplexed by Holt’s speech.

From another but related perspective, Holt’s attitude toward Rollins and racial justice was deeply embedded in his ideological view of the “Negro Problem” which assumed a gradualist approach to racial issues. Gradualists like Holt were liberals who publicly opposed segregation but argued that changes should come gradually and in small increments. This gradualist viewpoint was well articulated in a 1947 statement by nine presidents of prestigious Southern universities and colleges, one of whom was Hamilton Holt. They took issue with a section of the 1946 Commission on Higher Education report which recommended the immediate end to school segregation. “It would be unwise and impractical,” the presidents warned, “to end the segregation of white and negro children that exists in the schools and colleges of the South by any kind of government edict. This problem should be solved by the Southern people themselves and cannot be done overnight.”(14) Holt articulated his own version of gradualism when he told Rollins students, “our loyalties to Rollins and its ideals were not to precipitate a crisis that might and probably would promote bad race relations, but to work quietly for better race relations, hoping and believing that time would be on our side.”

What Martin Luther King called “the tranquilizing drug of gradualism,” has a long racial history in the United States, beginning with the theory of the gradual abolition of slavery through the gradual end of segregation. It continues even today with those who support the Black Lives Matter movement but are uncomfortable with its demands for immediate changes. Gradualist racial theory contains troublesome moral problems which liberals (such as Hamilton Holt) chose to look past. If all citizens have equal rights, it is morally indefensible to argue that the enjoyment of those rights should be postponed so as not to disturb the status quo. Justice delayed is justice denied, observed William Gladstone. “Wait,” said Martin Luther King, means “Never.” So when Holt suggested waiting “quietly for better race relations,” he not only discounted the reality of Southern unyielding determination to preserve the Jim Crow system, but he turned a blind eye to the moral ramifications of that statement.

A second problem with the belief in racial gradualism concerns the degree to which those who advocate it become complicit in the very system they condemn. By preventing African Americans the enjoyment of seeing Hurston’s play, by denying Bethune Cookman students the opportunity to observe a class at Rollins and by refusing to play to the football game because of OWU’s African American player, meant Rollins College, in effect, became an unintentional participant in the segregation system. Despite all the denials of complicity, the fact remained, when successive administrations succumbed to local pressure and refused to confront local racial prejudices, they made the college appear to be fellow travelers with white supremacy segregationists.

Thus, over the years, Rollins presidents left a legacy of racial inertia that became a standard pattern of behavior. Five years after Holt retired the Supreme Court issued the Brown desegregation decision, which meant that ensuing Rollins administrations would not face the kind of racial decisions that had confounded the college for the previous seven decades. But still they hesitated. Hugh McKean (1951-1969), who was president at the time of the Brown decision, was undoubtedly swayed by previous decades of racially complacent administrations. Rather than acting proactively, he moved cautiously and so did his immediate successors. Two decades after the 1954 Brown desegregation decision Rollins still remained a mostly white institution. It would take several more years before administrations began enrolling a meaningful number of African American students, the consequences of a history of racial timidity and equivocation.

ENDNOTES

1. Wenxian Zhang, et. al., “Race and Sports in the Florida Sun: The Ohio Wesley Football Game of 1947.” Phylon, 56 (2019), 59-81. On November 22, the Rollins Trusties issued a public statement making the claim that “in the best interests of racial relations, they are unwilling to take action which might interfere with the good progress now being made in Florida, and especially in the local community. Rollins, therefore, has decided to cancel the game.”

What racial progress? Segregation was still deeply imbedded in the area’s social life. African Americans were still robbed of their dignity, still prevented from voting and still subject to mob violence and lynching. Had Rollins leaders come to the point of willful blindness to prevailing racial injustice of the segregation system or did they know but decided to set aside actual conditions in order to justify their decision? In either the case, the trustees could not avoid the charge of moral obtuseness. “Statement of the Board of Trustees, Rollins College.” Rollins College Archives

2. “.Remarks by Hamilton Holt at the Annie Russell Theatre. Rollins College Archives. Quoted in Sandspur, December 4, 1947.

3. Sandspur, December 4, 1947

4. Apparently the student was referring to the post-World War II Holocaust revelations). Sandspur, December 4, 1947.

5. Sandspur, December 4, 1947.

6., Ibid.

7. “Negro Woman Holds Chapel Spellbound” Sandspur, March 11, 1931.

8. Letters in Rollins Archives.

9. On the Sentinel article see Orlando Weekly May 29, 2019. The now classic study of the Groveland Four is Gilbert King, Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New America. 2013

10. “Tribute to Mahatma Gandhi.” Copy of speech in Rollins Archives.

11. Copy in Holt Papers.

13. Bethune to Holt, February 22,1949; Holt to Bethune, February 25, 1929. Holt Papers

14. Address at Bethune Cookman College. March 17, 1950. Holt Papers.

15. See Rollins College Center For Racial Justice and Inclusion website