Wenxian Zhang

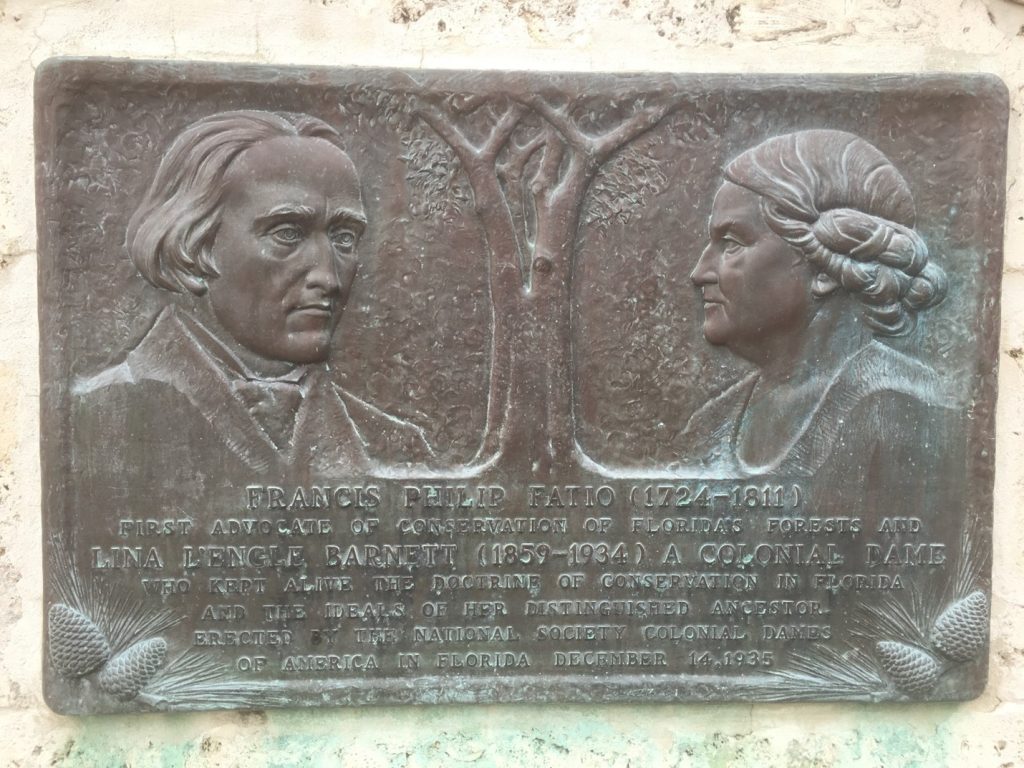

In the nearly ninety years since its dedication, the coquina garden bench has been a popular student gathering spot at Rollins College. Coquina is a rare form of limestone composed of the shell fragments of ancient mollusks and other marine remains; and since the first Spanish colonial period, coquina has been used for masonry work along Florida Atlantic coast. Designed by Leno Lazzari, the garden seat came with a bronze plaque noting “Francis Philip Fatio (1724-1811), first advocate of conservation of Florida’s forests, and Lina L’Engle Barnett (1859-1934), a colonial dame who kept alive the doctrine of conservation in Florida and the ideals of her distinguished ancestor. Erected by the National Society, Colonial Dames of America in Florida, December 14, 1935.” Originally located next to the Annie Russell Theatre, this bench with the memorial marker was first moved closer to a student dormitory, then relocated at the back of the Mills Memorial Center before its restoration near the Knowles Memorial Chapel in December 2023.

Francis Philip Fatio: A Pioneer Planter and Slave Owner in Colonial Florida

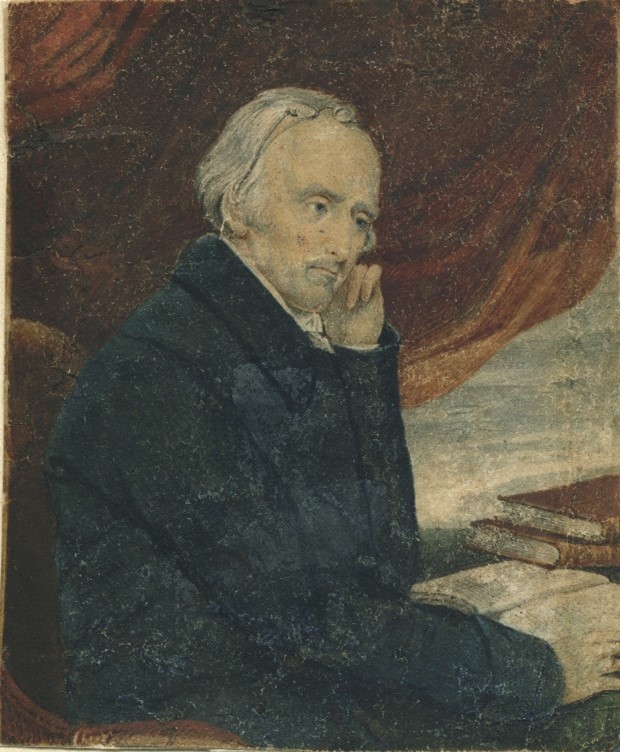

Born in Vevey, Switzerland, on August 6, 1724, to an aristocrat family of Italian and Swiss heritages, Francis Philip Fatio received his education from the University of Geneva.[1] However, instead of pursuing a legal career as his parents John David Fatio and Pauline Muller hoped, Fatio became a lieutenant in the Swiss Guard and fought in the War of Austrian Succession in the 1740s. While stationed in Nice, France, he met Marie Madeleine Crispell of Sardinia and after their marriage in 1748, the Fatios purchased property near Nice and began to grow sweet orange, lime, olive, and other fruit trees and vineyards.[2] During 1759-1771, Fatio joined his brother Michael to become a merchant in London. With the conclusion of the Seven Years’ War in 1763, Spain ceded Florida to Great Britain in exchange for control of Havana, Cuba. Sensing new business opportunities, Fatio formed a partnership with others to secure a British crown grant of 10,000 acres in the newly acquired East Florida colony and in 1771, he charted a ship loaded with fine European wines, china, glass, silver, furniture, and an extensive library and sailed from England for North America.[3]

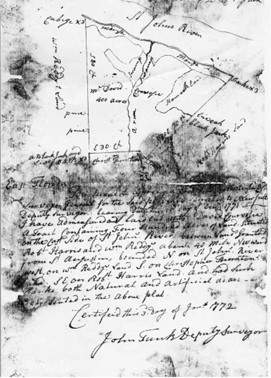

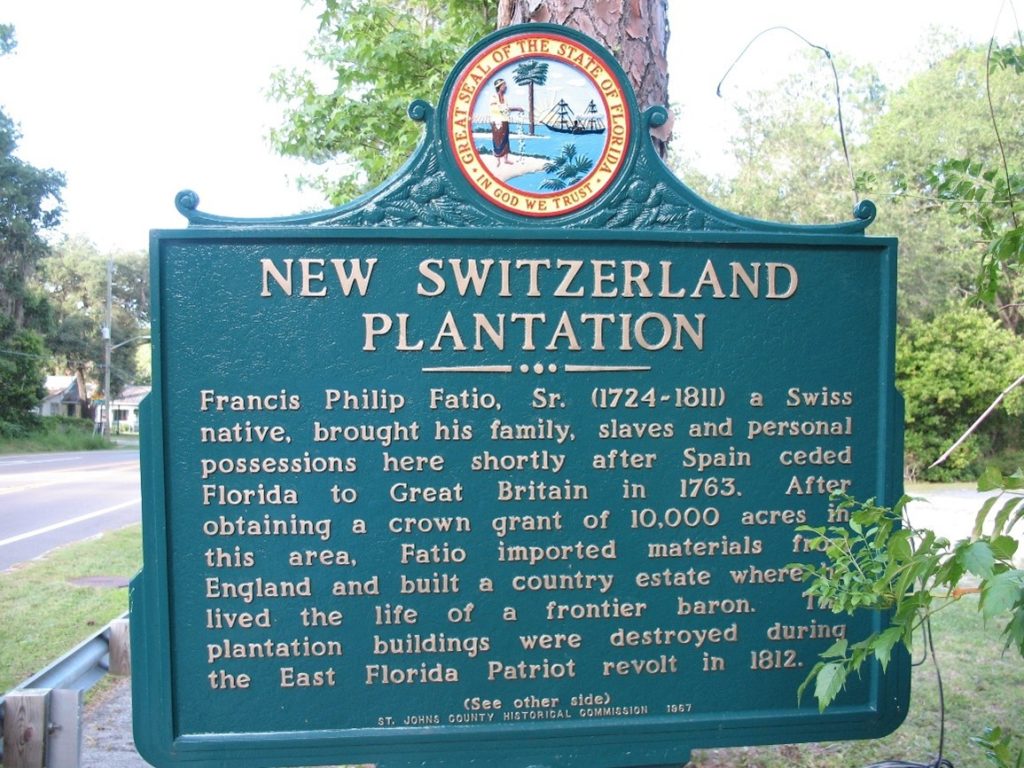

Arriving in St. Augustine along with his wife and five children, Fatio brought a large stone bayfront house for his family, and then quickly set up plantations and lived the life of a frontier baron in Florida.[4] His New Castle Plantation, located south of the St. Johns River, specialized in growing indigo, which produced a blue dye in demand by the textile industry. In 1774, during his explorations of the southern colonies of British North America, acclaimed American naturalist and writer William Bartram described visiting Fatio and his New Castle Plantation. According to Bartram, Fatio “has a very large Indigo Plantation, on a high Hill on Et. side of the River. This very civil gentleman showed me his improvements. his Garden is very neat & contains a greater variety than any other in the Coliny, he has a variety of European Grapes imported from the Streight, Olives, Figs, Pomegranates, Filberts, Oranges, Lemons, a variety of garden flowers, from Europe &c.”[5] Fatio had another plantation named Nice, but his New Switzerland Plantation, on the east bank of the St. Johns River thirty miles north of St. Augustine, was the largest of all with 10,000 acres; it soon became one of the most prominent plantations of colonial Florida.[6] As one of the leading citizens with sufficient means in British East Florida, Fatio also benefited from merchandise trade across the Atlantic and “kept a vessel constantly plying between the New and Old Worlds, carrying the products of the one and bringing back comforts and luxuries from the other.”[7] At New Switzerland, Fatio constructed a large country house with materials imported from England for his family when they were not in St. Augustine. Called El Palacio by Spaniards, with piazzas, balconies, and festival rooms, the two-story house measured 30 by 40 feet became the primary residence for Fatio. New Switzerland also had a dwelling for overseers, a covered house for carriages, a warehouse, workshops for carpenters and blacksmiths, corn and fowl houses, a turpentine shed, a hospital for his laborers, and the slave quarters of multiple cabins.[8]

Since their arrival, Fatio and his descendants experienced turbulent times and lived through multiple “changes of political allegiance” from the British colonial period (1763-1783) and the second Spanish period (1783-1821) to American territory (1822-1845) and statehood (1845-).[9] Native people also had endured these changing European powers at same time. When the Europeans first arrived in Florida in the early sixteenth century, the indigenous people who lived along the St. Johns River in east-central and northeast Florida were known as the Timucuans. However, when Florida was turned over to the British, there were almost no Florida natives left, having died from European diseases or tribal conflicts. The last Timucuans may have moved to Cuba along with the departing Spaniards in 1763.[10] By taking advantage of British policy of converting land once held by Native Americans into private property, Fatio, a shrewd businessman, quickly grew his New Switzerland into a thriving plantation in colonial Florida.[11] .

During the American Revolution, while Florida remained loyal to the British crown, Fatio rendered his services to British forces and was given a staff position in Charleston, South Carolina.[12] At the end of the war, the British retained East Florida, which Fatio believed was an important asset, valuable for its fertile interior and abundance of trees.[13] In 1782, Fatio penned a lengthy report, significant for its commentaries on forest conservation as well as for its emotional appeal, entitled “Considerations on the Importance of the Province of East Florida to the Empire (on the supposition that it will be deprived of its Southern Colonies) by its Situation, its produce in Naval Stores, Ship lumber, & the Asylum it may afford the Wretched & Distressed Loyalists.”[14] In this report on the considerations of East Florida dated December 14, 1782, Fatio argued that “proper Provincial Laws should be made to prevent setting on fire the Pine bearing Lands, to regulate the Boxing of Trees for Turpentine, to prohibit the extirpating the young saplings and to fix the number of Trees that should always remain on every acre.”[15] For his foresight on the strategic importance of Florida and his first call for tree preservation, Fatio has been called “the father of forest conservation in Florida.”[16]

Politically conservative and deeply invested in Florida, unlike other British settlers who chose to leave when the peninsula was returned to Spanish control in 1783, Fatio stayed behind and aligned himself with Spanish colonial government until his death in 1811. The second Spanish rule (1783-1821) was a chaotic period in Florida history. With only limited military presence in St. Augustine and Pensacola but few new settlers, the Spanish authorities had no effective control on the region but relied on supports from large plantation owners such as Fatio, “who was held in such high consideration that his influence was little less than that of the governor; that all classes looked up to him and applied to him for advice in every matter of importance…”[17] Accordingly, Fatio became a wealthy “baron” haughty enough to challenge even Spanish military and government officials.[18] Throughout his four decades of living in the new continent, Fatio not only collaborated with both British and Spanish authorities and helped take over land once occupied by Native Americans, but also played a key role on the rise of the “disruptive plantation economy” in colonial Florida.[19]

Slavery was an essential part of the plantation economy in the American South, and Fatio was a direct beneficiary of slave labor, a common practice of large colonial plantation owners in Florida. In 1766, with a 500-acre land grant, even William Bartram had six enslaved African Americans during his brief, unsuccessful attempt to run a plantation at Little Florence Cove along the St. Johns.[20] In that historical context, Fatio was operating as many others did in Florida. When setting up his New Switzerland in 1774, Fatio and his partners spent £2,430 for eighteen enslaved Africans and put them to work clearing high ground, erecting fences, harvesting timbers, and constructing buildings.[21] After the British ceded Florida back to Spain under the Treaty of Paris, Fatio bought out shares owned by his business partners and “held a public auction of personal property they held in common, including fifty slaves sold in family units for a net price of £1,686. Among the men sold were sawyers, squarers, field laborers, and a cooper (the latter sold for £71 Sterling). A cook, a young female house servant, and several field hands were among the women sold.”[22] In his 1801 Census Return, Fatio listed eighteen white members of his family, one free person of mixed race, four free African Americans, and eighty-six enslaved people, totaling 109 “souls” in his care.[23] Moreover, he had 58 heads of cattle, 14 horses, 150 sheep, and 60 pigs, and owned five houses in St. Augustine, two houses in the country, two store houses, five work sheds, two horse barns, and 27 cabins for African American slaves, a total of 43 buildings to be maintained.[24] In addition, records noted that some enslaved African Americans also escaped from Fatio’s plantation.[25] A prominent case was Luis Fatio Pacheco, son of a skilled slave carpenter in New Switzerland. After running away, Pacheco lived among Seminoles in North-central Florida and was a survivor of the Second Seminole War in the early nineteenth century.[26]

As a large plantation owner and operator eagerly building up his wealth and power, Fatio held prejudiced views toward Native Americans, specifically members of the Creek tribes who came into Florida in the late 1700s, later becoming known as Seminoles. When describing the best lands that remained unsettled, he complained about “the frequent Eruptions of those Wild Indians,” calling them “Scum,” “Vagabonds and Outlaws.”[27] Competing for same natural resources during the second colonial period, planters like Fatio often clashed with Creeks and Seminoles, who also faced aggressive pressures from the north pushed by Anglo-American colonists for their resettlement. On August 13, 1812, one year after his death, Fatio’s New Swaziland plantation was sacked, and his El Palacio looted and burned by a band of Creeks.[28]

Fatio’s legacy today is that of a visionary who saw the need to preserve Florida’s forestry resources more than a century before others joined this cause. “He was a man of vision and business acumen, and he was convinced that Florida had a future, if its natural resources were properly developed and conserved.”[29] When he first argued for conservation in Florida, it was largely in his business interest as a plantation owner and manager of the colonial era, but Fatio foresaw that Florida’s forests were under threat long before anyone was worried about natural resources getting depleted.

Lina L’Engle Barnett: A Colonial Dame and Conservation Advocate

Fatio’s rich family stories are a vibrant part of the Florida history. All his five children – Louis, Francis Jr., Louisa, Sophia, and Philip – reached adulthood and their children lived through the British and Spanish colonial rules and the U.S. territory period and statehood. The Fatio family survived the 1812 Creek attack, and their descendants continued to build wealth and influence for generations in Florida.[30] While Louis took care family business overseas in Sardinia and Philip served in the Spanish diplomatic missions in Philadelphia and New Orleans, Francis Jr. stayed home to help his father’s business in Florida. His son, Francis Joseph Fatio, subsequently served as city alderman and mayor of St. Augustine in the 1820s. Fatio’s elder daughter Louisa wed British army officer Colonel John Hallowes, and his younger daughter Sophia married Captain George Fleming, who operated his own plantation, Hibernia, across the St. Johns River from New Switzerland with 32 slaves.[31] Their grandson, Francis Philip Fleming, later served as the 15th governor of Florida from 1889 to 1893 and was the president of the Florida Historical Society from 1906 until his death in 1908.[32]

Carolina Hallowes (Lina) L’Engle was a great-great granddaughter of Francis Philip Fatio Sr. Born in December 1859 at an army post in Texas, her father was William Johnson L’Engle, a surgeon in the United States Army.[33] Growing up in Florida but receiving her education in Virginia, she married Bion Hall Barnett at the St. John’s Episcopal Church of Jacksonville on April 30, 1880. Carolina H. L’Engle became Lina L’Engle Barnett and began to advocate women’s causes, participating in social service groups such as the YWCA, the Woman’s Life Saving Corps, the Woman’s Club of Jacksonville, and the Traveler’s Aid International. She was also a member of the Colonial Dames of Florida and the Daughters of American Revolutions, groups that celebrate their hereditary ties to early U.S. history.[34]

As vice president of the Colonial Dames of Florida and chairman of the Conversation Committee, Barnett pursued her passion in preservation, which eventually extended from history to the pristine natural resources in Florida. Barnett became an ardent advocate for the conservation of Florida forests, and often spoke out on the importance of sustainability, warning about the dangers of forest fires and tree over-harvesting without replanting. According to Minerva P. Jennings, 11th president of the Colonial Dames of Florida, “Her latter years were devoted almost exclusively to accumulating information on this important subject [forest conservation in Florida], and to passing it on, whenever possible, to organizations and individuals. She was interested in the trees of Florida not only because of their beauty, and their value to the landscape, but because of their great economic value to the State, as a protection to the soil, and as the sources of lumber and naval store – distinct financial assets.”[35]

Coquina Garden Bench at Rollins

After the death of Lina Barnett in 1934, the Colonial Dames of Florida erected a historical marker to honor her dedication for Florida conservation and in memory of the life of her great-great grandfather Francis P. Fatio of colonial era. One of Barnett’s children was Madeleine Camp of Jacksonville, a key member of the Colonial Dames of Florida in the 1930s. She shared the same French heritage in the Huguenot Society with the mother of Alfred Jackson Hanna ’17 ’45H, an accomplished Florida history scholar and chair of the History Department at Rollins.[36] Through this personal connection and their shared passion for Florida history, the Colonial Dames of Florida presented the coquina garden seat with bronze plaque for the 50th anniversary celebration on the founding of Rollins College. “The Colonial Dames of Florida, with the gracious cooperation of Rollins College, as a tribute to the fine work in History which this superb Institution of Higher Culture is offering, and in recognition of its semicentennial, are erecting this memorial to Francis Philip Fatio and his equally distinguished great-great granddaughter, because of his pioneer work for conservation, and her unremitting endeavor to further the cause.”[37] On Saturday, December 14, 1935, a ceremony was held in the Knowles Memorial Chapel. Presided over by Hanna, the event opened with the Rollins College Choir singing “God Save the King,” followed by salute to the American flag, speeches on the Fatio family heritages, and brief profiles of Francis P. Fatio and Lina L. Barnett. After the bench presentation by Jennings and unveiling of the memorial by Camp and other Fatio descendants, the gift was accepted by President Hamilton Holt. The ceremony continued with a prayer by Dean Charles A. Campbell of Knowles Memorial Chapel and “the Star-Spangled Banner” by Rollins Choir, and finally concluded with a reception in the chapel gardens.[38]

The Fatio/Barnett garden seat was originally located at the back of the Annie Russell Theatre. However, it had to be taken down shortly after due to inappropriate installation in 1935. After the Colonial Dames of Florida raised objections, the bench was moved next to the courtyard of Mayflower Hall, a Rollins women’s dormitory built in 1930 that had a connection with the colonial history of the nation.[39] After the Mills Memorial Library was renovated in the 1980s, the bench was moved to the back the building at the center of the campus, facing the College Dinning Hall and the Cornell Student Center for the next 30 years. In 2018, it was taken down once again to make room for the renovation of the Mills Memorial Center into Kathleen W. Rollins Hall. However, during the disassembling process the coquina bench fell into pieces and had to be put into storage; and it took five years for a stonemason to repair the damage and reassemble the bench for its reappearance on campus. On December 1, 2023, 88 years after its initial dedication, with the presence of Betty Elmore Gilleland, a great-great granddaughter of Susan Fatio L’Engle (granddaughter of Francis P. Fatio), the coquina garden bench was rededicated in the Knowles Memorial Chapel Garden, just a few yards away from its original location at the back of the Annie Russell Theatre.

In spring 2024, through his senior capstone project, Liam King ’24 conducted historical research with special focus on Francis P. Fatio as a slave owner and plantation operator during colonial Florida. When the bench was originally presented in 1935, Jennings did not made any reference to Fatio’s enslaved African Americans, but vaguely noted that “he proceeded to the St. Johns River, and settled three plantations, built houses for himself and his numerous operatives and employees, and commenced the cultivation of indigo, the extraction of turpentine, the planting of orange groves and his raising of sheep.”[40] As a part of Locating Slavery Legacies in the American South, King raised the critical question on the appropriateness of the historical maker on Rollins campus, a liberal arts institution dedicated to educating students for global citizenship and responsible leadership.[41] Today, the coquina garden seat along with the memorial plaque is not only a tribute to efforts made by Barnett in forest conservation, but also a spot for members of the Rollins academic community to reflect upon Fatio’s roles in the development of Florida and a dark chapter in Florida history.

Acknowledgement

Author gratefully acknowledges the constructive review provided by Dr. Leslie Poole of Environmental Studies.

[1] Susan L’Engle, Notes of My Family and Recollections of My Early Life (New York, 1888), 5.

[2] William Scott Willis, “A Swiss Settler in East Florida: A Letter of Francis Philip Fatio,” Florida Historical Quarterly 64:2 (1985), 174-188.

[3] Ibid, 175.

[4] Susan L’Engle, 10.

[5] William Bartram, “Travels in Georgia and Florida, 1773-74: A Report to Dr. John Fothergill,” Transactions of the American Philosophical Society 33:2 (1943), 145.

[6] George Lansing Taylor Jr., “New Switzerland Plantation Marker, St. Johns County, FL” (2010). George Lansing Taylor Collection Main Gallery, 5068. https://digitalcommons.unf.edu/historical_architecture_main/5068.

[7] Susan L’Engle, 10.

[8] “New Switzerland,” Florida History Online, University of North Florida, December 18, 2020, https://history.domains.unf.edu/floridahistoryonline/?s=New+Switzerland+.

[9] Walter C. Hartridge, “The Fatio Family: A Book Review,” Florida Historical Quarterly 31:2 (1952), 142.

[10] Jerald Milanich, “Florida’s Indians: Past and Present,” Explore Magazine 3:2 (Fall 1998), https://research.ufl.edu/publications/explore/v03n2/indians.html.

[11] Nancy O. Gallman, “Reconstituting Power in an American Borderland: Political Change in Colonial East Florida.” Florida Historical Quarterly 94:2 (2015): 169–191.

[12] Susan L’Engle, 11.

[13] Nancy Gallman, 170.

[14] Francis Philip Fatio to Major John Morrison, “Considerations on the Importance of the Province of East Florida to the British Empire (on the supposition that it will be deprived of its Southern Colonies), By its Situation, its produce in Naval Stores, Ship Lumber, & the Asylum it may afford to the Wretched & Distressed Loyalists,” December 14, 1782, Francis Philip Fatio, Florida Vertical Files, Rollins College Archives, Winter Park, Florida.

[15] Ibid.

[16] “Lover of Trees Honored Dec. 14: Rollins to Dedicate Plaque to Fatio,” Sunday Sentinel Star, Dec. 1, 1935, 9.

[17] Susan L’Engle, 17.

[18] Susan Parker, “I Am Neither Your Subject Nor Your Subordinate,” El Escribano: The St. Augustine Journal of History 25 (1988), 43–60.

[19] Susan R. Parker, “Success Through Diversification: Francis Philip Fatio’s New Switzerland Plantation,” in Colonial Plantations and Economy in Florida, ed. Jane Landers (Gainesville: University Press of Florida, 2000), 69-82; Nancy Gallman, 169-191; Susan Parker (1988), 43–60.

[20] “William Bartram’s Plantation,” The Historical Marker Database, https://www.hmdb.org/m.asp?m=48683.

[21] “New Switzerland,” 2020.

[22] Ibid.

[23] William Willis, 187.

[24] Ibid.

[25] Susan Parker (1988), 59; (2000), 79.

[26] George Klos, “Blacks and the Seminole Removal Debate, 1821-1835.” Florida Historical Quarterly 68:1 (1989): 55–78; Alcione M. Amos, “The Life of Luis Fatio Pacheco: Last Survivor of Dade’s Battle.” Pamphlet Series 1:1 (2006). Seminole Wars Foundation, Inc.: 6. https://seminolewars.org/wp-content/uploads/2018/05/Life-of-Luis-Pacheco.pdf.

[27] Francis Philip Fatio to Major John Morrison, 1782.

[28] Susan L’Engle, 28.

[29] Minerva P. Jennings, “Francis Philip Fatio,” Presentation of Coquina Garden Seat with Bronze Plaque in Memory of Francis Philip Fatio (1724-1811) Father of Conservation in Florida and His Equally Distinguished Great-Great-Granddaughter, Lina L’Engle Barnett (1859-1934) to Rollins College, by The National Society, Colonial Dames of America in the State of Florida, 14 December 1935. Fatio Garden Seat, 05C Buildings and Grounds, Rollins College Archives, Winter Park, Florida.

[30] Susan Parker (2000), 71.

[31] Margaret Seton Fleming Biddle, Hibernia: The Unreturning Tide (New York: Vantage Press, 1974).

[32] Walter C. Hartridge, 143.

[33] Minerva P. Jennings, “Lina L’Engle Barnett,” 1935.

[34] Ibid.

[35] Minerva P. Jennings, “Lina L’Engle Barnett,” 1935.

[36] “Fatio, Francis Philip Correspondence,” 05 Buildings & Grounds, Rollins College Archives, Winter Park, Florida.

[37] Presentation of Coquina Garden Seat with Bronze Plaque, 1935.

[38] “Fatio Honored at Rollins: Colonial Dames Dedicate Bench,” Orlando Evening Star, December 15, 1935, 12; “Fatio, Barnett Are Give Honor: Dedication of Coquina Seat Held December 14,” Rollins Sandspur, December 18, 1935, 1, https://stars.library.ucf.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1444&context=cfm-sandspur.

[39] Wenxian Zhang, “Mayflower Hall,” Rollins Architecture: A Profile of Current and Historical Buildings (Winter Park, FL, Rollins College, 2009), 56.

[40] Minerva P. Jennings, “Francis Philip Fatio,” 1935.

[41] Claire Strom and Rachel Walton, “Uncovering Connections to Slavery on a Florida Campus,” Legacies of American Slavery: An Initiative of the Council of Independent Colleges, August 29, 22024, https://legaciesofslavery.net/2024/08/29/uncovering-connections-to-slavery-on-a-florida-campus/.