Written by Wenxian Zhang

Since the sixteenth century, when Spaniards first arrived in St. Augustine, European colonization led to the troubling unsettlement of Native Americans, profoundly changing the faces of the American continent and the Florida peninsula. While both Florida and the Philippines remained Spanish colonies for centuries, there was no record of any Asians by the time Florida attained statehood in 1845. A few Asians began to arrive in Florida in the years after the Civil War, concentrating mainly in railroad construction, agriculture, laundry, restaurant, and grocery businesses. Their population grew very slowly until after World War II, when discriminatory immigration policies were finally lifted. The 1965 Immigration Reform Act, the openings of Walt Disney World and other tourist attractions, the end of the Vietnam War, and the thriving Sunbelt economy all brought many new immigrants to the southernmost state in America. Shaped by multiple waves of immigration and socioeconomic factors, Asian Americans are among the fastest-growing census groups in the Sunshine State. Like in other parts of the United States, Asian Americans’ experiences in Florida are rich and diverse, filled with fascinating stories of struggles and triumphs since their arrivals in the late nineteenth century. In celebration of Asian Pacific American Heritage Month, a few notable Asian Americans are highlighted here to pay tribute to the progress and contributions made by Asian Americans in the land of sunshine.

Lue Gim Gong, Florida’s Chinese American Citrus Wizard

Lue Gim Gong with his pet rooster March in DeLand, Florida (Image courtesy of Florida State Library & Archives).

Lue Gim Gong was a Chinese American horticulturist who made noteworthy contributions to the state’s citrus industry. Born in Taishan, Guangdong Province, Lue left China at age fifteen and immigrated to the United States in 1872. He first worked in a shoe shop in San Francisco and soon moved with a group of Chinese to another shoe factory in Massachusetts, where he learned English at a local Chinese Sunday School, joined the Baptist Church, and became a Christian. There he met Fanny Burlingame, a volunteer teacher who greatly influenced Lue’s life. Intrigued by the fresh intelligence of the young Chinese, she invited Lue to live in her house as an “adopted” son.[1] He spent much time working in Burlingame’s large garden and conservatory filled with exotic plants. He was familiar with plants since he had worked in the orange groves in his hometown, where his mother taught him how to cross-pollinate blossoms and graft stock.

When the family purchased an orange grove in Florida, Lue joined them in DeLand in 1886. The severe freezes in the 1890s greatly motivated him to work on developing a strain of orange that would resist frost. He crossed the Florida Harts Late orange with a variety from the Mediterranean region, and the result was a sweet, juicy fruit that could endure severe weather. Named the Lue Gim Gong Orange, it was described as probably “the hardiest of all sweet orange varieties now commonly cultivated in America. It is a noteworthy fruit because of the length of time the fruit may be held on the tree.”[2] For his achievement, the American Pomological Society awarded a Silver Wilder Medal to his orange in 1911, the first time such an award was made for citrus. Even though Lue was called the “Wizard of Citrus Growers” and the “Chinese Burbank of Florida,”[3] fame did not bring him fortune. As his name spread, thousands of visitors came to his grove, and he would give away free samples of his fruit and plants. Three years before his death, his mortgage became overdue, and a public fund drive was held to save his property. It took seventy-five years to finally honor Lue when he was recognized as a “Great Floridian” by the Florida Department of State, and a memorial garden was dedicated in his honor in DeLand on October 15, 1999.[4]

George Morikami, a Japanese Pioneer with the American Dream

George S. Morikami and his dog in Delray Beach (Courtesy of Florida Memory, Florida State Library & Archives).

George Morikami’s life was a classic story of immigrants, an ambitious young man who traveled to America to seek opportunity and make a better life for himself and a better world for others. At the turn of the twentieth century, Japanese were recruited to Florida for land development opportunities. George Morikami was one of the early settlers of the Yamato Colony in South Florida led by Jo Sakai. Arriving in 1906 through an indenture, Morikami did three years of hard labor at Yamato. However, when the agricultural business collapsed, he did not even have the promised money to return to Japan when his sponsor died of a typhoid epidemic. Morikami had no choice but to remain at Yamato and work as best he could. After first working for an American family for room and board plus $10 per month, he soon realized he had to learn English to survive and prosper in the U.S. In 1910, he began to attend the local elementary school at age 24 while working as a farm laborer. Though his formal education only lasted for one year, he was able to speak, read, and write rudimentary English. In the following year, he returned to Yamato, cleared a half-acre of land, and planted tomatoes with borrowed seeds, fertilizer, and tools. By the end of the season, he not only paid off his debts but also made a profit of $1,000. With this money, he began to buy land in the nearby areas, planted larger crops, and hired others to work on his field. In the boom years of the 1920s, Morikami also went into the mail-order wholesale business where his produce was shipped to Washington, California, and many other places.

Against all odds and through hard work and ingenuity, Morikami, the last survivor of the Yamato experiment, became a successful landowner in Florida. Although he lost much of his fortune during the depression era of the early 1930s, he was able to hold a large parcel of land in South Florida. When the United States entered the war with Japan in 1941, the War Department confiscated the remaining Japanese holdings in the area and used part of the land for a U.S. Army Air Force complex.[5] Since miscegenation laws of the time prevented Japanese from intermarrying with whites, Morikami remained single all his life. Finally, in 1967, Morikami sought to become a U.S. citizen at age 82. A man of simple tastes, toward the end he lived hermit-like in a mobile home on land he had purchased in the closing days of World War II, finding pleasure in his closeness to nature. To repay for the opportunity provided to him, he donated forty acres of land and $30,000 to the State of Florida for an agricultural experiment station, and another forty acres to Palm Beach County for a public park, which later became the Morikami Museum and Japanese Gardens at Delray Beach, a living memorial and tribute to the contributions made by Asian American pioneers in the Sunshine State.[6]

Edmond Joseph Gong, First Asian American Legislator in Florida

Florida legislative senator Edmond J. Gong (Image courtesy of Florida Memory, Florida State Library & Archives).

Edmond Joseph Gong is the son of Joe Fred Gong, one of the cofounders of Joe’s Market, and a shining example of the new generation of Asian Americans. In 1914, Joe Fred Gong immigrated from China as a teenager to join his father’s laundry store in Georgia. He first tried his luck in Miami but struggled in the laundry business in the mid-1920s. That is the time he befriended Joe Wing and seized a new business opportunity in the fast-growing region of the state. Due to racial segregation in the Jim Crow South, Blacks were not allowed to shop in white-owned stores, so they decided to open a grocery store located at N.W. Third Avenue and 10th Street in Overtown, an African American neighborhood where there was little competition.[7] Joe’s Market was truly a family business, opening seven days a week from early morning to late evening, averaging 14 hours each day. While the parents ran the store, kids were expected to help as soon as they were old enough, from stocking shelves and marking goods to checking out groceries. Although the grocery business was hard work with long hours and a low profit margin, it offered new immigrants an opportunity to make an honest living and sustained the growth of the Chinese community in South Florida.

Eddie Gong was born in Miami in 1930. As the only boy in the household, his parents had great hope for him. Like any other first generation of Chinese immigrants, Joe Gong toiled and saved for his children’s education and a brighter future. Although he did not have the chance to receive higher education, he worked hard to provide such opportunities for his children and did not expect them to run a laundry or grocery store when growing up. Eventually, all Gong’s five children graduated from college and became successful professionals. Of Eddie’s four sisters, two became doctors, one a pediatrician, the other a radiologist, and two of his nephews are attorneys. Growing up in Miami, Eddie and his sisters had to help with their father’s grocery business, and there was no Chinese language school for the siblings to learn their native language properly. Unlike his father, however, Eddie was eager and ready to assimilate into mainstream American life. When he was a high school junior in Miami, Eddie Gong demonstrated his leadership skills and was named the president of the Boys Forum of National Government in Washington, D.C., which was sponsored by the American Legion to give youth an opportunity to observe the functions of the federal government. On August 5, 1947, Eddie Gong along with 102 other teenagers visited the White House and was warmly received by President Harry S. Truman.

Five years later, Eddie Gong graduated from Harvard University cum laude and attended Harvard Law School and the University of Miami afterward. As a second-generation Chinese American, he quickly discarded the traditional way of thinking of his parents and fully embraced American individualism and culture. In 1955, he published an article endorsing interracial marriage in American Magazine. Titled “I Want to Marry an American Girl,” this essay stood in sharp contrast to the anti-miscegenation debacle of his grandfather’s and father’s generations a few decades earlier.[8] Gong was the first Asian American ever elected to the Florida State Legislature, serving in the House of Representatives from 1963 to 1967 and the State Senate from 1967 to 1973. He later became an assistant US attorney for the Southern District of Florida and a public policy consultant.

Nelson Ying, Nuclear Physicist, Entrepreneur, and Community Leader

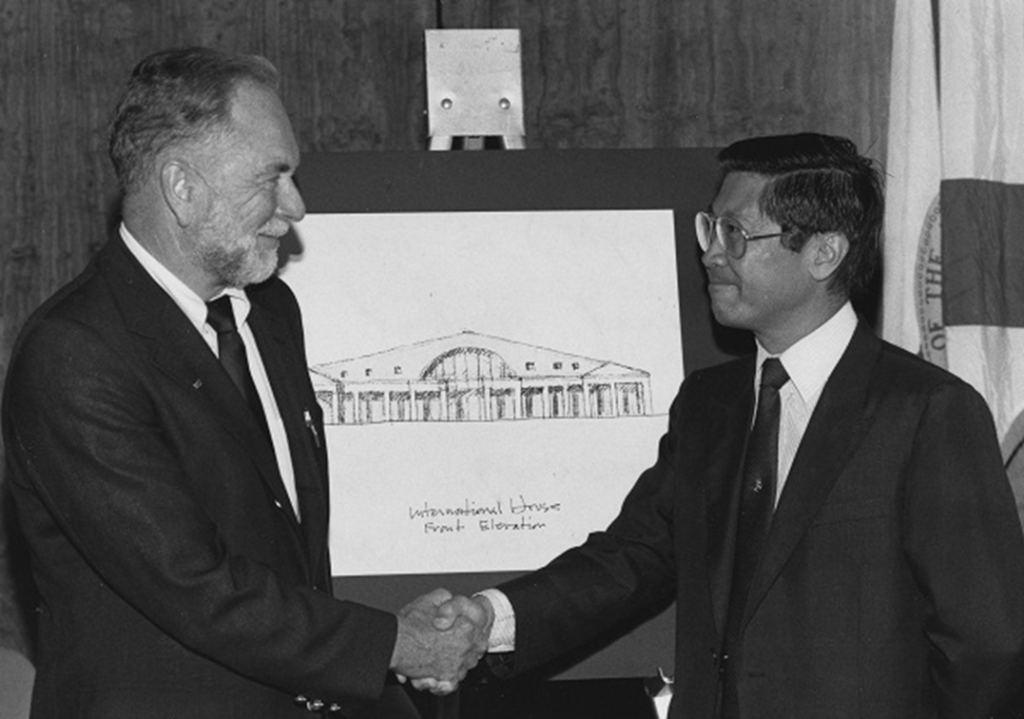

“Barbara Ying Center, Dr. Trevor Colbourn and Dr Nelson Ying” (1989). Special Collections and University Archives Exhibit Photographs. 23.

In 1955, Nelson Ying came to New York from Shanghai along with his parents, with only $600 in their pocket. After receiving his BS degree from the Polytechnic University in 1964, Ying continued his graduate studies at Adelphi University, earning a master’s and a PhD in Physics. First working as a NASA trainee and a captain in the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers, Ying later became a physics professor at the University of Central Florida, and then president and chief executive officer of the China Group, and of the Florida-based Quantum Nucleonics. With a strong belief in education and to inspire the science leaders of tomorrow, he created and sponsors the Dr. Nelson Ying Science Competition through the Orlando Science Center, where he serves on the Board of Trustees. The contest not only awards scholarships to aspiring students but also honors the referring science teachers and the school principals. As a trustee of the University of Central Florida Foundation, he financed the Barbara Ying International Center to commemorate his late wife and to improve the quality of student life on campus. In addition, Ying is a director of the Eastern States Buddhist Temple and a member of the Economic Development Commission of Mid-Florida. He also contributed to the construction of the new headquarters building for the Heart of Florida United Way, and the Patricia Ying Central Florida Distribution Center in Orlando.

Mimi McAndrews, First Asian American Woman Legislator in Florida

Democrat legislator Mimi K. McAndrews (Image courtesy of Florida Memory, Florida State Library & Archives).

Mimi McAndrews is the first Asian woman to serve in the Florida House of Representatives. Born and raised in Missouri, McAndrews is a Korean American who was adopted when she was two months old. After her brief marriage with a German Irish Caucasian failed, she moved to Florida and worked first as a salesclerk in a department store, and then as a receptionist at a Japanese steak house, where she met a Japanese chef who later became her second husband. Although she made efforts to be the perfect subservient little Japanese wife, that marriage did not last long either. McAndrews realized to be successful in her life, she needed to be more self-reliant and independent. Consequently, after receiving her bachelor’s degree from Florida Atlantic University in 1988, she enrolled at age 32 in the law school at Georgetown, where she was the president of the Asian Pacific American Law Students Association and became much more aware of her Asian American heritage. After graduation, she returned to Florida and ran successfully for the House of Representatives in 1992, becoming the first Asian woman in the state’s history of 150 years. After leaving the Florida legislature, McAndrews opened a consumer protection law firm in West Palm Beach and later became a CEO of a national safety council.

Stephanie Murphy, First Vietnamese American Woman in the U.S. Congress

Stephanie Murphy, U.S. representative for Florida’s 7th congressional district from 2017 to 2023. Official photo of the United States Congress (Public domain image)

Born in 1978 in Ho Chi Minh City, Stephanie Murphy left Vietnam with her family when she was six months old. After they were rescued by the U.S. Navy in the South China Sea, the family settled in Northern Virginia where she grew up. Murphy and her brother became the first generation in their family to attend college. With Pell Grants and student loans, she graduated from the College of William & Mary with a BA in economics in 2000. She then worked briefly as a strategy consultant for Deloitte Consulting in Washington, D.C., before enrolling at Georgetown University and earning her graduate degree from the School of Foreign Service in 2004. For the next four years, Murphy worked as a national security specialist in the U.S. Department of Defense, earning the Secretary of Defense Medal for Exceptional Civilian Service. After relocating to Florida, Murphy first worked as an executive of investment management at SunGate Capital and then taught business and entrepreneurship classes at Rollins during 2014-16.

The Pulse Night Club massacre in Orlando greatly motivated Murphy to go into public service. She ran as a moderate Democrat for Florida’s Seventh Congressional District, which consists of Seminole County and parts of northern Orange County, including downtown Orlando, Maitland, Winter Park, and the University of Central Florida. In the 2016 election, Murphy defeated the long-term Republican incumbent Rep. John Mica, becoming the first Vietnamese American woman and first Vietnamese American Democrat to be elected to Congress. While serving for three consecutive terms, Murphy was on the influential House Ways and Means Committee and the Armed Services Committee, as well as a member of the Blue Dog Coalition, the New Democrat Coalition, the Climate Solutions Caucus, and the Congressional Asian Pacific American Caucus. Reflecting upon her own immigration background and American experience, Murphy declared: “#IAmAnImmigrant & proud of it. Our nation’s diversity is its strength. Opportunity and freedom keep the American dream alive.”[9]

Ty Penserga, from High School Science Teacher to City Mayor

A Florida city commissioner and high school teacher, Ty Penserga has served as the mayor of Boynton Beach during 2022-25. Photo from Ty Penserga socials.

Ty Penserga is another Asian American public service professional in the Sunshine State. Born in the Philippines and immigrated to the United States as a young boy, he grew up in Palm Beach County. While attending Temple University, Penserga first demonstrated his passion for service. He was a senator in Temple’s Student Government and received the prestigious Diamond Award for his leadership, community service, and the creation of a longitudinal mentoring pipeline to uplift underprivileged teens in Philadelphia. After earning his BS in chemistry and biology, Penserga returned to Palm Beach County to teach high school sciences. He also attended Florida Atlantic University and received his master’s degree in biology and neuroscience. Originally intending to pursue a career in science but greatly motivated by the local politics in South Florida, Penserga decided to get into public service in his hometown of Boynton Beach instead. He ran and served as the District IV City Commissioner, Vice Mayor, and representative to Palm Beach County’s League of Cities and the Intergovernmental Forum. On March 8, 2022, Penserga defeated three other challengers to become the mayor of the third-most populous municipality in Palm Beach County. He is not only the first Asian American mayor in the history of Florida, but also the first openly LGBTQ-AAPI mayor elected in the state.[10]

Conclusion

Florida has been home to many notable Asian Americans, and the above featured are but a few more prominent Floridians of Asian descent in state history, who have played important roles in the development of the state across various fields, from agriculture, business and entrepreneurship, to education, healthcare, research and technology, community and cultural enrichment. Although the presence of Asians in Florida can be traced back to the Reconstruction era, for nearly a century their numbers remained low, and those early settlers had to endure not only economic hardship and cultural isolation, but also racial discrimination ingrained in the segregated South. Since the Civil Rights Movement and the immigration reform in the 1960s, along with the state’s overall population growth, Asian American communities began to form in large metropolitan areas such as Miami, Tampa, Orlando, Jacksonville, Tallahassee, and other parts of the state. In our global age of the twenty-first century, Asian Americans, with their rich and diverse ethnic and cultural heritages, have been making increasingly significant contributions to Florida’s economic development, cultural diversity, and international connections.

[1] Ruthanne Lum McCunn, “Lue Gim Gong: A Life Reclaimed.” Chinese America: History and Perspectives 3 (1989), 117-135.

[2] Harold Hume, The Cultivation of Citrus Fruits. New York: Macmillan, 1926.

[3] “Lue Gim Gong: The Citrus Wizard 1860 – 1925.” West Volusia Historical Society, DeLand, Florida, 1999.

[4] Great Floridians 2000. Tallahassee, Florida, Florida Department of State, 1999, https://files.floridados.gov/media/693491/great_floridians_pdf.pdf.

[5] Morikami Museum and Japanese Gardens, “The Yamato Colony: Bridging the Cultures of Japan and Florida.” Delray Beach, Florida, 2023, https://morikami.org/yamato-colony/.

[6] Morikami Museum and Japanese Gardens, “George Sukeji Morikami’s Legacy.” Delray Beach, Florida, 2023.

[7] Sam Jacobs, “Markets Kept Overtown Stocked.” in Bob Kearney ed., Mostly Sunny Days: A Miami Herald Solute to South Florida’s Heritage. Miami Herald Publishing, 1986, 129.

[8] Eddie Gong, “I Want to Marry an American Girl.” In Judy Yung, Gordon Chang, and Him Mark Lai eds., Chinese American Voices: From the Gold Rush to the Present, Berkeley: University of California Press, 2006, 240-246. https://doi.org/10.1525/9780520938328-042.

[9] “Great Immigrants, Great Americans: 2020 Great Immigrants Recipient.” Carnegie Corporation of New York, 2020, https://www.carnegie.org/awards/honoree/stephanie-murphy/.

[10] Jorge Milian, “Boynton Beach Election: Ty Penserga Trounces 3 Mayoral Challengers, Including Anti-mask Advocate.” Palm Beach Post, March 8, 2022, https://www.palmbeachpost.com/story/news/local/boynton/2022/03/08/boynton-beach-election-ty-penserga-first-lgbtq-mayor-city-history/9417950002/.