Written and edited by Rachel Walton and Emma McAdoo

This is part two of a two-part blog post written and edited by Librarian Rachel Walton and Olin Library student worker, Emma McAdoo. It is inspired and informed by the Women at Rollins historical exhibit. All research and writing for the Women at Rollins exhibit was conducted by a team of seven student curators as a part of Dr. Claire Strom’s Fall 2024 Public History class. They are listed here as coauthors and collaborators: Kayleigh Calaway, Faith Chaney, Aislinn Gara Grady, Brynna McDonald, Reilly Merritt, Arianna Pazmino, and Justin Perez. Finally, the College Archives team was essential in researching and creating the exhibit. All sources and images, if not attributed otherwise, come from the Archives’ rich collections.

As we turn our attention to the experiences of women in higher education, we see that many of the nation-wide movements and feminist causes we’ve already explored are reflected in the local context of Rollins College. Women have been a part of Rollins since before its inception and have been key to the College’s success in many ways over the eras. Let us explore the historical microcosm of Rollins to (a) learn how women’s rights and sexism were at play in our own backyard over the years and (b) celebrate the female leaders who pushed us forward and challenged the status quo for the benefit of all.

College Policies and Culture

Established as a frontier school in 1885, Rollins needed women both as students and as faculty in order to run and stay open. Rollins’ first graduates were women and the campus’ student body has always been majority female, especially during wartime when young men were drafted into the service. Today, 55% of the faculty and 61% of students are female. Furthermore, many campus leaders and donors over the years were powerful women who saw value in the liberal arts tradition and wanted to make their mark on higher education. These women were particularly devoted to improving and creating new spaces on campus for the Rollins community, and we continue to benefit from their generosity today. Despite women being essential to the college’s existence and prosperity, historical records show that women at Rollins consistently encountered discrimination and sexism both in the realm of college policies and in general campus culture.

Traditional American attitudes and conservative thought about women’s place in society strongly influenced the college’s earliest policies, often in ways that negatively impacted women. For example, dorm policies instituted early curfews and policed the movements of female students in public spaces well into the 1980s. Such restrictions never applied to male students. Likewise, uniform policies also reflected traditional gender roles by highlighting “desirable” feminine qualities such as modesty, cleanliness, and ladylikeness. While some of these archaic college policies were a detriment to female students’ experiences in the modern era, the absence of policies also fostered discrimination in some areas of women’s lives on campus.

Photo of three female Rollins students in front of Orlando Hall in the late 1950s.

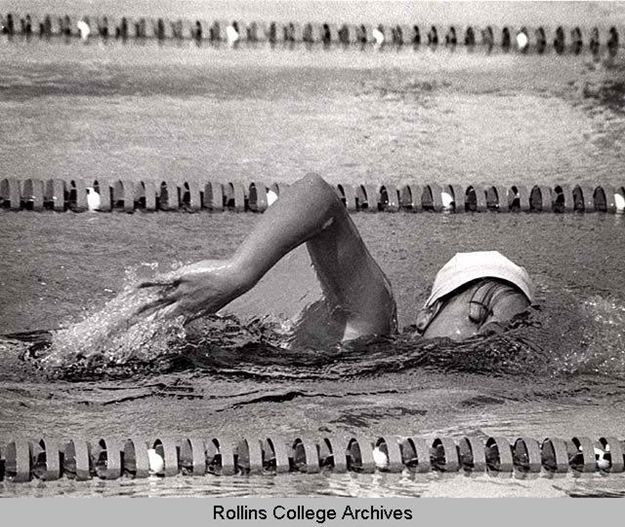

Women’s sports did not receive adequate funding at the college until the implementation of Title IX in 1972, which aimed to equalize the treatment of women at US universities and colleges. The main focus of Title IX was athletics, as women’s sports were seriously underfunded on campuses across the country compared to male sports. Rollins College was no different. Title IX improved the situation for women’s athletes at Rollins, allowing them to gain access to more resources and combat poor treatment and discrimination in comparison to their male counterparts. However, some inequities, like less-than-adequate facilities or lack of team promotion, remain an issue according to current female student athletes and coaches.

Wendy Clark, member of the Rollins College Women’s Swim Team. Photo taken in 1974, just two years after Title IX took effect in higher education.

Additionally, the lack of a maternity policy until 2008 placed female staff and faculty in a problematic position when trying to build a family. Dr. Fiona Harper advocated for a maternity policy in 2008, with help from other faculty and staff as no document of that kind existed yet at the College. A lack of a maternity policy exemplified the role that gender norms play in higher education and underscored the systemic challenges women face when trying to balance academic careers with motherhood. The 2008 maternity policy gave female faculty six weeks of paid leave, which was an improvement, but it only applied to one parent. If two Rollins faculty had a child, only one could use the policy. In 2021, the maternity policies at Rollins were updated and renamed parental leave policies. Both faculty parents are now granted a leave from teaching during the semester of a baby’s birth with pay, while staff receive six weeks of paid leave.

While campus policies were a critical component of the female experience at Rollins, other aspects of campus life had more to do with social norms and college culture of the day. One example of this was the Miss Rollins Pageant, which debuted in 1958; this competition was monumental in defining gender dynamics on campus. This first pageant consisted of 14 undergraduate women, each picked to represent various on-campus organizations, specifically sororities. Several contestants were selected by fraternities, representing the organization under the title of “sweetheart.” The contest began with a swimsuit competition, followed by a fashion show of designer clothing. The winner of the 1958 Miss Rollins beauty contest was Tanya Graef, a freshman student nominated by the fraternity, Sigma Nu. Tanya ended up withdrawing from Rollins after her win to pursue a modeling career and soon after married a Rollins classmate. Each year, the Miss Rollins pageant winners’ names were added to the Tiedtke Cup, named for Mr. Tiedtke due to his donations to the event. By 1967, the process of judging for the pageant began to shift from beauty into one that also considered the intellect and character of the women involved. While the 1958 pageant was based on beauty first and foremost, judges of the 1971 contest stated the guidelines for their judgment were based on “amiability, congeniality, self-confidence, appearance, and poise.”

The Tiedtke Cup was awarded to the Miss Rollins pageant winner every year between 1958 and 1971. It resides in the College Archives.

Nonetheless, fashion remained the core of the event, with each woman modeling a casual outfit, a cocktail dress, and a one-piece swimsuit. Gradually, excitement for the pageant turned to disinterest or, for some, disgust. As second wave feminism took hold across the nation and our campus, the pageant was met with increasing opposition from those who decried its exclusion of men and non-Greek life organizations as well as its inherent objectification of the young women involved. An article in the 1971 Sandspur questioned whether the pageant would continue, and indeed it did not.

In 1971 there were fifteen contestants for Miss Rollins. When the scores were tallied, Andrea Boissy was the second runner up, Lynn Seabury the first runner up, and Barbara Postell the winner. This was the last year that the pageant took place.

Barbara Postell was the 13th and final Miss Rollins winner in 1971, who was also a freshman at the time of her win. An economics major and avid performer at the Annie Russell Theatre, Postell had modeled throughout childhood. Although she already boasted of a successful modeling career, working with Vogue and Harper’s Bazaar in New York and gaining praise in the New York Times, Postell returned to Rollins after her summer modeling work to complete her economics degree. It may be that by the 1970s, the culture around women’s education had shifted; college women like Barbara seemed to prioritize their education and college experience over other opportunities in ways that previous generations of women had not.

Female Firsts: Early Women Trailblazers

Rollins College owes much of its success to early female figures, whose dedication and resilience carved a path for future generations. Lucy Cross turned her idea for a college in Florida into a reality, and Rollins was born. Students Clara Guild and Ida May Missildine were the first women to graduate from Rollins, excelling in subjects that men traditionally dominated. These women laid a strong foundation for future female scholars and challenged the academic norms of their time. Similarly, faculty members, such as Grace Livingston and alumna Frances Gonzales, demonstrated female leadership in academics and advocated boldly for themselves and their students.

Known as the “Mother of Rollins College,” Lucy Cross was a pioneer in Florida’s higher education. In 1879 she founded the Daytona Institute to provide an eight-month curriculum for local and visiting children in what was then the frontier Florida. Her dedication to the advancement of education drove her to push for another institution, one focused on college education for new generations. This passion project became a reality the following year when the Congregational Church was so impressed with Ms. Cross that they took a leap of faith and supported the idea. The church assigned Cross to a committee of all male church leaders who were tasked with finding a location for the new school. A donation from businessman A.W. Rollins (after whom the institution would be named) and other wealthy elites in the central Florida area secured Winter Park, Florida as the home of what would soon be Rollins College. The college was incorporated in April of 1885 and classes started in November of the same year, welcoming young men and women alike.

Lucy Cross, 1839-1927. The black and white version of this image is from Rollins College Archives and Special Collection; however, the colorized version of the photograph is courtesy of Winter Park Magazine.

Clara Louise Guild enrolled as a charter student on November 4, 1885. And though she faced challenges with her studies due to her limited prior education in some subjects, Clara persevered through the demanding classical curriculum. She dedicated herself to mastering subjects like Greek, geometry, physics, and botany. Clara became a part of Rollins’ first senior class in May 1890 alongside another female student – Ida May Missildine – establishing a legacy of female academic excellence at the college in its earliest moments. In 1898, Clara Louise Guild returned to Rollins earning a Master of Arts and founding the Rollins Alumni Association. She went on to serve as the association’s first president and established a tradition of alumni connection and community. On Rollins College’s 50th anniversary in 1935, she was awarded the Rollins Decoration of Honor.

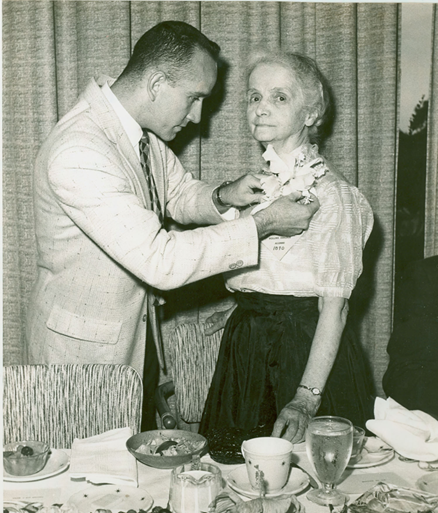

Ida May Missildine enrolled in Rollins in 1887, driven by her passion for music. She became one of the College’s first students to study piano and voice. Ida’s legacy is especially significant, as she made history just three years later, graduating in 1890 alongside Clara Guild as one of Rollins College’s first graduates. After earning her A.B. degree, Ida chose to stay at Rollins as an assistant piano instructor, passing on her musical expertise to future generations and enriching the college’s musical community. In 1957, she too was awarded the Rollins Decoration of Honor during Reunion Weekend.

Ida May Missildine receiving her Decoration of Honor, 1957.

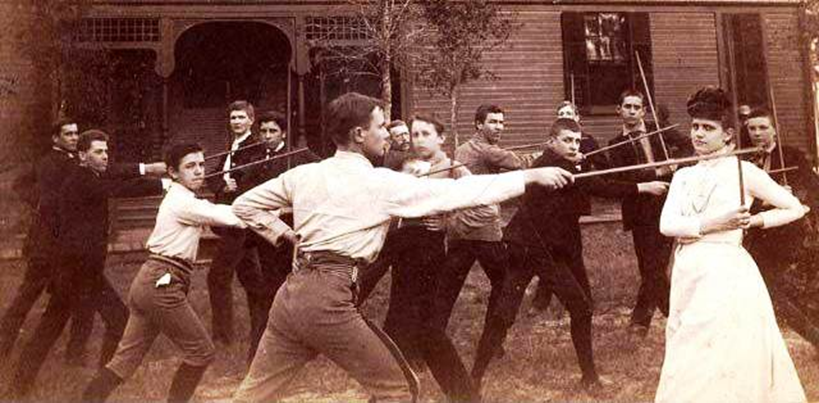

Grace Livingston (later known as Grace Livingston Hill) was one of the first female faculty at Rollins, serving from 1889 until 1891. She taught calisthenics and gymnastics and in the 1890s, this included “club swinging, fencing, free work, wand, dumb-bell and hoop exercises,” as well as basketball and “Greek posture” class. In one memorable early faculty meeting Grace had to push for a change in the rules regarding female gym uniforms, which were outdated and hard to workout in. She proposed a modest yet practical outfit, consisting of dark blue serge suits, high-neck blouses, and a divided skirt, which allowed freedom of movement while maintaining propriety. Despite initial resistance from the faculty, who were hesitant about the “bloomer” style and wanted to separate the sexes for class due to concerns of propriety, Grace passionately defended the uniform’s modesty and appropriateness, even demonstrating it herself in front of the group. Ultimately, her persistence led to approval by the College President, marking a significant step forward in women’s athletic apparel at Rollins. After her years at Rollins, Livingston became most known as a popular novelist, but she remained in touch with friends from her teaching days and sent autographed copies of her books to the College library.

Miss Grace Livingston teaching fencing to Rollins students, circa 1890.

Known affectionately as Fanny, Frances Gonzales was one of Rollins College’s first international students, arriving from Cuba in the late 1890s with her sister Trinidad, following their brothers Eulogio and Jacinto. Their family fled Cuba due to the chaos leading up to the Spanish-American War. Fanny had a notable academic journey at Rollins. She studied as a Special Art Student (1897–1899), attended the Rollins Business School (1900–1901), and continued in the Preparatory School until 1902, paving the way for future international students. In 1916, Fanny returned to Rollins College as a Spanish teacher, strengthening the connection between the institution and its dedication to growing Hispanic heritage on campus.

The Women Who “Built” Rollins: Female Leaders in Campus Philanthropy and Fundraising

Female philanthropists have had a significant impact on Rollins College, donating money toward many of the campus’ most iconic buildings. Mary Louise Bok Zimbalist, Frances Knowles Warren, Jeannette Genius McKean, and Kathleen W. Rollins are just some of the key donors that have developed and improved our beautiful campus through ambitious building projects. In addition, Rollins’ first female president, Rita Bornstein, was deeply dedicated to not just campus expansion and growth but also to campus-wide advocacy around issues of equity and inclusion.

Mary Louise Bok Zimbalist, born in 1876, contributed significantly to Rollins, including the construction of the Annie Russell Theatre, named after her friend and famous actress. Zimbalist funded the theater to ensure Russell could continue her work in Florida, where she directed Romeo and Juliet and performed the plays In a Balcony and The Thirteenth Chair. The theater, which opened in 1932 under President Hamilton Holt’s leadership, remains central to student education today and is a beloved spot of campus. Frances Knowles Warren, another wealthy benefactor of the College, made notable contributions to campus buildings, including a $162,805 donation for the construction of Knowles Memorial Chapel, which she dedicated to her father — a founder, benefactor, and college trustee. The chapel was dedicated the same year as the Annie Russell Theater, 1932, and the two buildings stood as gems on campus, especially in the wake of the Great Depression when so many colleges lost funding or closed. Warren also gave more than $120,000 for the Warren Administration Building in 1946, which still stands.

President Hamilton Holt with Frances Knowles Warren at the groundbreaking ceremony for the Warren Administration building on February 8, 1946.

Jeannette Genius McKean — a philanthropist, artist, and first lady to President Hugh F. McKean (1951 to 1969) — was also instrumental in Rollins’ development, particularly the area of art and design. In 1942, she founded the Charles Hosmer Morse Museum, named after her grandfather. The museum, still in operation today, has one of the most extensive collections of Tiffany glass in the world. Jeannette would also help furnish Elizabeth Hall, named after her mother Elizabeth Morse Genius in 1945.

Edyth Bassler Bush, a former actress and playwright from Chicago, married businessman Archibald Granville Bush and retired from acting to focus on writing plays. She wrote La Gamine, which was performed at Rollins in 1956 to benefit Winter Park Hospital. Archibald made a significant impact on Rollins, donating $800,000 to fund the Bush Science Center, which opened in 1969 one year after his death. After the passing of her husband, Edyth donated an additional $615,000 to complete the building and also endowed a chair of mathematics. Her legacy continues today through her charitable foundation and the Edyth Bush Institute for Philanthropy and Nonprofit Leadership at Rollins, established in 2015.

Kathleen W. Rollins, a 1975 graduate of Rollins who went into the telecommunications sector, donated $10 million in 2018 to establish Kathleen W. Rollins Hall, a campus center and student hub with special focus on student career readiness and advancement. She also endowed the recently created Women in Finance program (2019), aiming to support women’s careers in the finance sector and open new doors for them upon graduation.

Aside from these larger donations, other women have also impacted the college landscape in critical ways over the years. Harriet Cornell’s philanthropy has left a lasting impact on Rollins College, with her name gracing the Harriet W. Cornell Fine Arts Museum (now the home of the Rollins Museum of Art), the Cornell Art Center, and more. “Mother of Rollins” Lucy Cross, donated $5,000 toward the $50,000 Lucy Cross Hall of Science in 1925. Later in the 1930s, Virginia Huntington Robie, a prominent local designer, contributed furnishings and her interior design expertise to the furnishing of Pugsley and Mayflower Halls. Philanthropist and feminist Hattie M. Strong donated $60,000 to fund Strong Hall, a women’s dormitory, in 1939 and another $125,000 supported Corrin Hall in 1947.

And women continue to shape the landscape of Rollins today. Virginia Nelson ‘55 helped fund the Virgina Nelson Rose Garden – a cherished spot in front of the Knowles Memorial Chapel and Annie Russell Theatre. Upon her death in 1992, Nelson’s daughters, who both attended Rollins, donated $10 million to the school, one of the largest donations in the college history. In addition, because Nelson was an avid supporter of the music program, the Rollins Music Building is named in her honor. More recently, in 2022, Sally K. Albrecht ’76 – a well-known choral composer and conductor – donated $1 million toward the construction of a new state-of-the-art studio theatre as part of the Tiedtke Theatre & Dance Centre complex.

President Rita Borenstein in her office at Rollins College, date unknown. Twenty years after retiring from Rollins, Bornstein passed away at the age of 88, following a long battle with Parkinson’s disease. Despite her condition, she remained headstrong and positive in her later years and stayed active within the campus community.

It was not until over a century after its founding that the college had its first female president. Rita Bornstein, also the first Jewish president at Rollins, transformed the institution during her 14-year tenure (1990 to 2004) by overseeing major campus expansions and significantly raising the college’s academic profile. As a visionary, Bornstein led the most ambitious fundraising campaign in Rollins’ history, securing $160.2 million to support academic programs, scholarships, faculty, and facilities. Her efforts significantly strengthened the college’s financial health, with the endowment more than quintupling. Additionally, Bornstein’s tenure saw the fully funded addition, expansion, or renovation of 25 campus facilities, marking the largest building boom at Rollins since the 1960s.

A trailblazer in education and a fierce advocate for Title IX, President Bornstein also played a crucial role in ensuring compliance with this critical legislation. Her leadership brought greater awareness to the challenges faced by female students, faculty, and staff, fostering an inclusive and safe environment. Importantly, Bornstein championed innovation by introducing programs in film studies, international business, and sustainable development, as well as establishing the Rollins College Conference Plan for first-year students to support their transition into college life.

Advocates for Sexuality, Women, and Gender Studies at Rollins

In the 1970s, the Women’s Liberation Movement sparked transformative discussions across the United States. These conversations resonated strongly on college campuses which served as outspoken hubs for young people’s social activism throughout the 1960s and 70s. In a 1971 article for the Sandspur titled “Women’s Lib Hits Rollins,” student Karin West argued passionately that women’s rights deserved equal recognition to men’s. Her words directly challenged the pervasive “MRS. Degree” fallacy — the assumption that female college students were more focused on finding husbands than advancing their careers through their education.

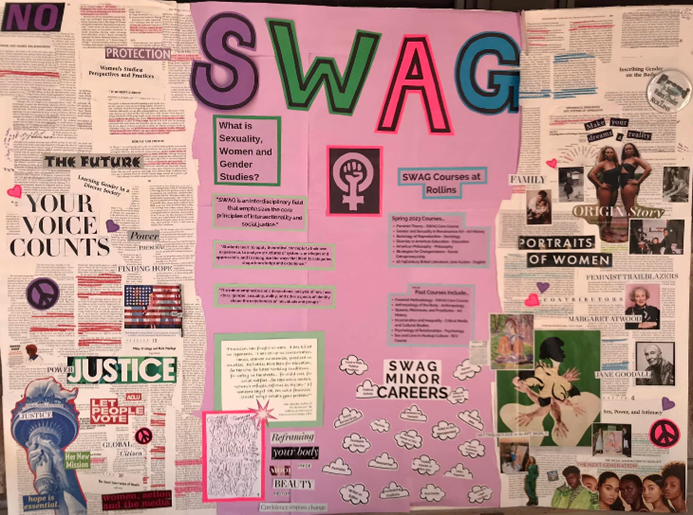

By 1974, a Women’s Studies program was offered at Rollins through the Adult Continuing Education Program, but it was not until 1981 that Sexuality, Women, and Gender Studies (SWAG) courses was officially added to the general curriculum offerings. The program’s addition was led by Dr. Rosemary Keefe Curb, a professor and department chair of English Literature.

Image of Professor Rosemary Keefe Curb in 1985 when her book Lesbian Nuns was published. This image was printed in an article from the Tampa Tribune discussing Curb’s book, which garnered much attention from media outlets.

Before her career as a professor, Keefe spent eight years as a Dominican nun in Wisconsin. In 1965, she left the convent, citing its oppressive nature, and pursued a Ph.D. in English Literature with a focus on feminist theatre. During this period, she also came out as a lesbian. Joining Rollins in 1979, she quickly became a prominent advocate for women’s rights, pushing for gender equity in academia. Her courses on feminist and lesbian theater gained wide respect, and in 1985, she published Lesbian Nuns: Breaking Silence, a groundbreaking book exploring sexuality within convent life. The celebrated book is part of Olin Library’s Fiat Lux collection, and it earned Keefe and her coauthor a spot on the very popular Gay Byrne’s “Late Late Show” in September of 1985.

Image Courtesy of the Rollins College SWAG Facebook Page. Uploaded in February of 2023.

Today, students at Rollins can earn a minor in SWAG. One student, alumna Hannah Cody, who graduated as the class of 2016 Valedictorian, designed her own interdisciplinary Gender Studies major. Her senior thesis, “Through the Grapevine: A Mixed-Methods Analysis of Rape and Retaliation on a College Campus” evaluated the social dynamics surrounding rape and sexual assault allegations, and the fear of retaliation amongst survivors at Rollins College. After going on to work at UNICEF as a child rights and business advocacy consultant, Cody completed a master’s degree in public administration and human rights at Columbia University in 2021. Since then she has worked with companies as an expert in international labor standards and as a sustainability project specialist.

Female Student and Alumna Activism

From pushing for campus integration and advocating for the needs of Black students on campus to pioneering new DEI initiatives, Rollins’ female student leaders and alumni have made a lasting impact on our community.

Marion Galbraith Merrill ’38 was an active leader at Rollins while a student. She was a member of the Student Council, the Social Service Committee, and the Interracial Club. Following her graduation, she served briefly as an executive assistant at the college. Merrill was also an activist and advocate for racial equality. She attended Martin Luther King’s “I Have a Dream,” speech at the National Mall in 1963 and later marched with him to Montgomery, Alabama in support of the Civil Rights movement. In 1964, Marion, as an alumna, tried to pressure Rollins administrators to take the steps needed to integrate Rollins’ student body. In a letter to Dean Hanna, Ms. Merrill threatened that she was in touch with the Head of the U.S. Commission on Civil Rights and would report on the school’s inaction if matters did not change. In 1965, Rollins enrolled its first Black students and in 1970 the college matriculated its first Black graduates.

Twenty Black Student Union (BSU) members pose for their student organization’s yearbook photo in Spring of 1973. This is the first BSU photo ever included in the Tomokan yearbook. BSU President Kristia Jackson stands on the far left.

Krisita Jackson ‘73 was an Economics major and the first elected president of Rollins’ Black Student Union (BSU). As president, Jackson emphasized the importance of integration into campus life and community building. She worked closely with the Office of Admissions to increase Black student enrollment and initiated a very successful Black Awareness Week, securing $2,500 in funding from the college to host campus-wide events. In an interview, Jackson recounted the lively student government meeting where the BSU proposed the Black Awareness Week budget, during which members of the Kappa Alpha fraternity in attendance displayed the Confederate flag. Despite their dissent, Jackson noted that the opposition “did not prevail.” Black Awareness week featured a variety of events, including talks by famous civil rights leader Jesse Jackson as well as Alcee L. Hastings, a prominent Florida lawyer and political leader. These events drew attention from the Orlando community, sparking newspaper headlines like “Rollins’ Blacks Aim to Break Student Apathy,” and “Rollins Celebrates Diversity Week.” Later on in the 1990s Black Awareness Week morphed into a cultural celebration called Africana Fest.

Erica Mungin ‘24, was the first Black and Filipina female president of Student Government Association (SGA) at Rollins. During her term, Mungin focused on advancing and improving Rollins’ newly drafted DEI policy. Her administration also reintroduced the Homecoming tradition, in an effort to raise school spirit and camaraderie among students. And, in the same spirit as Black Awareness week and Africana fest, Mungin’s administration launched a new campus event — The Cultural Festival. The goal was to celebrate and acknowledge the many diverse backgrounds represented by students across our campus. Erica earned a dual degree in Philosophy and Political Science. She is also a passionate and skilled photographer. Currently Erica is exploring graduate programs to further her expertise and impact in her field.

Looking Back, Looking Ahead

Its title inspired by Senator Elizabeth Warren’s 2017 refusal to be silenced in the Senate, the children’s book “She Persisted” was written by Chelsea Clinton and illustrated by Alexandra Boiger. It celebrates thirteen American women across history who persevered in the face of adversity. The book’s core message is about determination, courage, and standing up for what’s right, encouraging young readers—especially girls—to chase their dreams despite challenges.

The legacies of women in the fields of education, advocacy, philanthropy, and beyond have all left an indelible mark at Rollins, showing how women have been necessary for the college’s success from the beginning. Their achievements, which we try to celebrate here in a small way, set a standard of excellence and innovation that inspires us. By learning from their stories and supporting the women around us, we can continue our journey toward equality in our own spaces today.

As we look back on the remarkable progress women have made in our country over the past century—from securing the right to vote to breaking barriers in education, politics, and the workforce—we see that every step forward has required persistence. The hard-fought victories in women’s rights have shaped the opportunities we have today, but they also serve as a reminder of the work still ahead. Let the banner of “Nevertheless, She Persisted” be a call to action for us all.