By: Wenxian Zhang

Susan Tyler Gladwin (1873-1952), an early Rollins graduate who received her A.B. in 1899, was one of the American teachers who went to Southeast Asia in 1901 to help establish a public education system during the American colonial period in the Philippines. Known as Thomasites because they embarked on the cross-Pacific journey from San Francisco to Manila aboard the U.S. Army Transport ship Thomas, this group of men and women is considered a precursor to the U.S. Peace Corps, representing one of the first large-scale volunteer efforts to bring American culture and values to another country through education at the turn of the twentieth century.

Susan T. Gladwin was born on July 19, 1873, in Higganum, Connecticut, the fourth child of Stephen Nelson Gladwin and Abby Maria Reed.1 After the death of her two brothers, young Susan moved to Melrose, Florida, along with her parents, and later the family settled in Titusville, Florida. In 1891, Gladwin enrolled in Rollins at age 18. Four years later, she graduated from Rollins Academy and became a sophomore at Rollins College. Throughout her college years, Susan remained active in student life. She was the president of Friends in Council, an early student organization in the college’s history.2 In addition to being the critic of the Delphic Society, a literary society and the first student organization at Rollins, she was also the associate editor of the Rollins Sandspur, the oldest continuously running student newspaper in Florida.3 Her two-page story “A Southern Home” was published in the December 20, 1897, issue of the Sandspur.4 On May 24, 1899, after completing her senior thesis “Some Records of our Indian Policy,” Gladwin graduated from Rollins with a Bachelor of Arts degree.5 She soon began to teach in Merritt’s Island school system, about twenty miles from her hometown of Titusville, Florida. A year into her teaching work, an unexpected opportunity arose that profoundly changed Susan’s life and career path.

After the conclusion of the Spanish-American War of 1898, along with Puerto Rico and Guam, the Philippines became a U.S. colony, marking the end of several centuries of Spanish dominance in the Americas, Asia, and the Pacific. To continue the educational work started by the US Army in the Philippines, President William McKinley appointed William Howard Taft as the head of a new commission. On January 21, 1901, the Taft Commission passed Education Act No. 74, which established the Department of Public Instruction with a mission of establishing a public school system throughout the islands.6 Consequently, the Taft Commission authorized the deployment of 1,000 educators from the U.S. to the Philippines to promote Americanization through English, reading, writing, and other subjects, including manual trades, arts, and athletics. A call for applications was quickly issued, and many young American college graduates were eager to join the new educational adventure in Southeast Asia. Gladwin did not even apply herself. However, with the right credentials, she was recommended by Dr. Elijah Clarence Hills, Professor of Modern Language and Dean of the Faculty at Rollins, to his friend Fred W. Atkinson, first General Superintendent of Public Instruction in the Philippines, and was soon accepted into the program.7

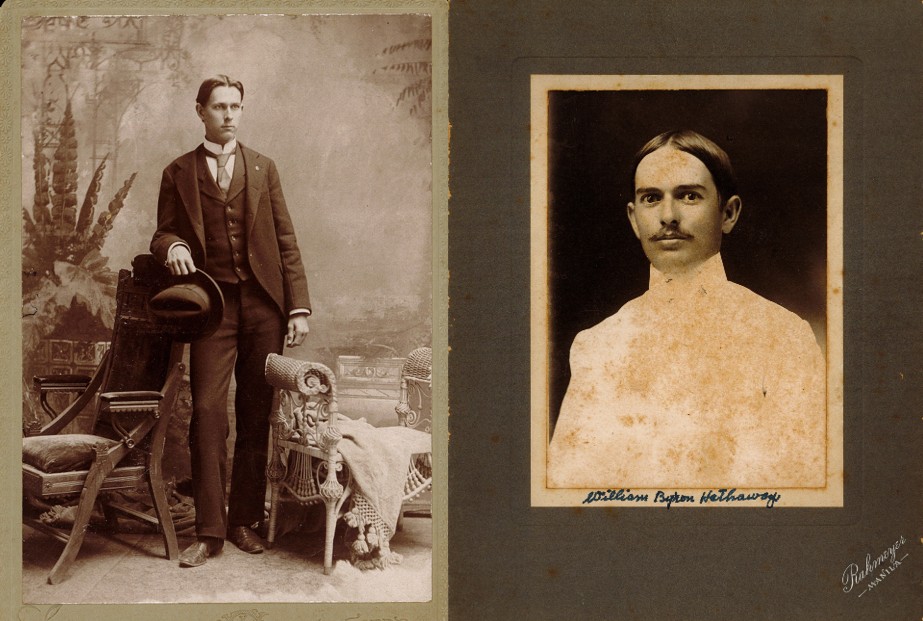

In the Rollins College Archives there is Gladwin’s unpublished typewritten manuscript Letters from the Philippines: 1901-1904 (Rollins Collection G463 G5 1904), which contains 200 letters that Susan wrote to her parents and diary entries she kept for herself while teaching in the Philippines over the three-year period, including 46 letters in 1901, 74 in 1902, 57 in 1903, and 23 in 1904. Since Gladwin never married in life, she remained close to her parents until they passed away, and her keen observations and detailed recordkeeping have made this manuscript a rich primary source material that vividly documents the educational adventures of some young American teachers in the Philippines in the early twentieth century. Her extensive writings reflect not only the progress made in school classrooms and the friendships developed with other Thomasites and local Filipinos, but also the hardship endured living in the tropical climate, as well as firsthand accounts of local cultural celebrations, racial tensions, and civil unrest in the Philippines under the new American colonial power at the turn of the century. Gladwin’s travel writing started with a letter dated June 15, 1901, from the Division of Insular Affairs of the War Department in Washington, D.C., notifying her that she had been accepted as a teacher in the Philippines. Then another letter of July 1, 1901, from the quartermaster of the U.S. Army instructed her to travel from Titusville, Florida, via sleeping train to San Francisco to catch the Special Teacher’s Transport scheduled to sail on July 23, 1901. Aboard USAT Thomas were 346 men and 180 women, representing 193 colleges and universities from 43 states, including Harvard, Yale, Cornell, University of Chicago, University of Michigan, and University of California.8 Besides Susan Gladwin, Louis Atwater Lyman, Rollins Class of 1899, was also aboard the ship. According to the records kept in the National Archives, as an English teacher, Gladwin’s annual salary was $900 in 1902 and 1903, and $1,080 in 1904.9 In comparison, Louis Lyman earned $1,000 as a teacher in 1902 and $1,400 as executive bureau clerk in 1903; however, he only stayed in the Philippines for one year and resigned from the program on August 19, 1902.10 In addition, another Rollins graduate also participated in the teaching program in the Philippines. William B. Hathaway was appointed on October 4, 1901, and sailed on Thomas on October 16, 1901. He made $1,180 in 1902, $1,000 in 1903, and resigned on June 13, 1903.11 While teaching in the Philippines, Hathaway published a dozen letters about his experiences in Southeast Asia in the New Smyrna Breeze from January 1902 to March 1903.12

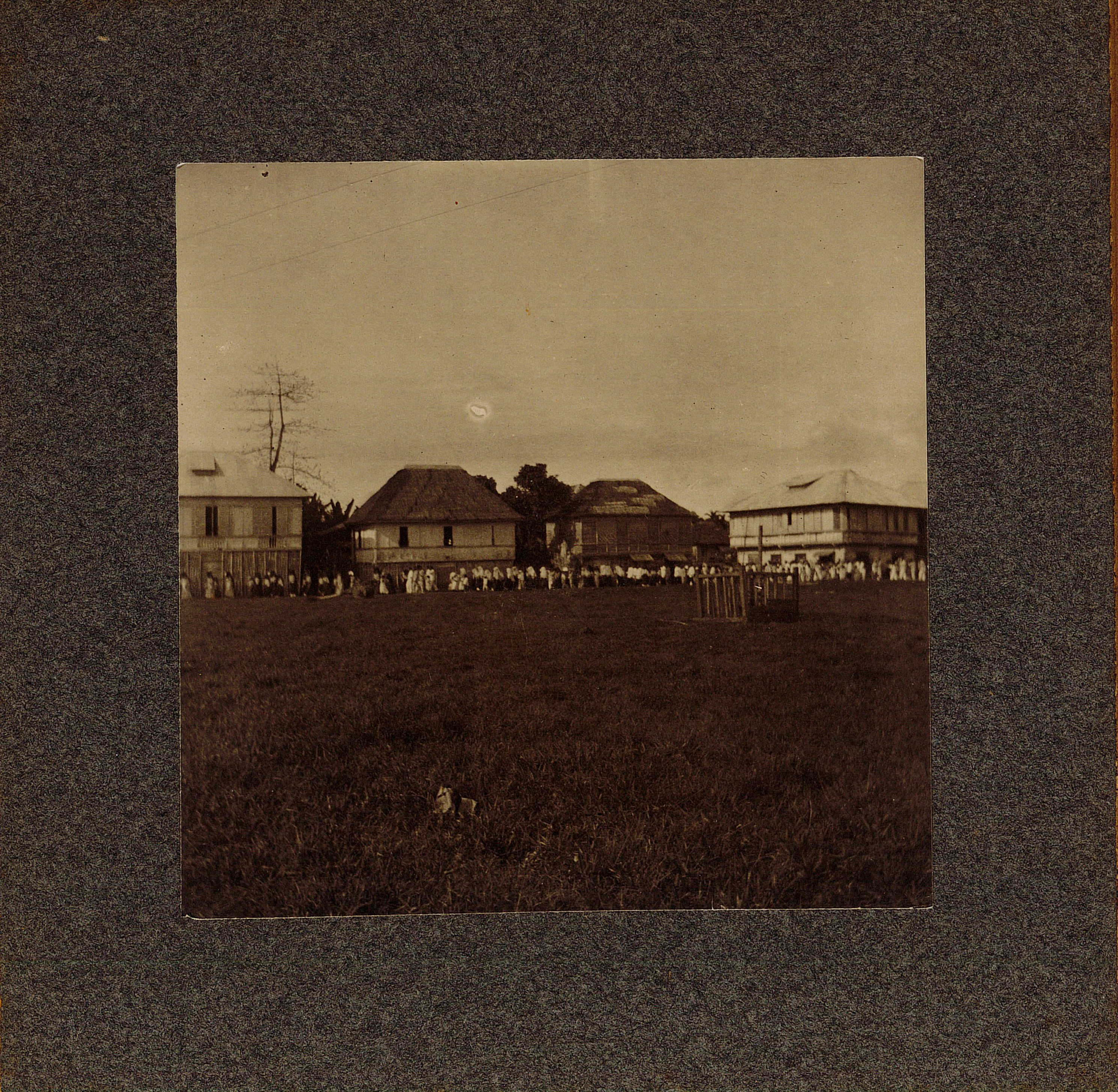

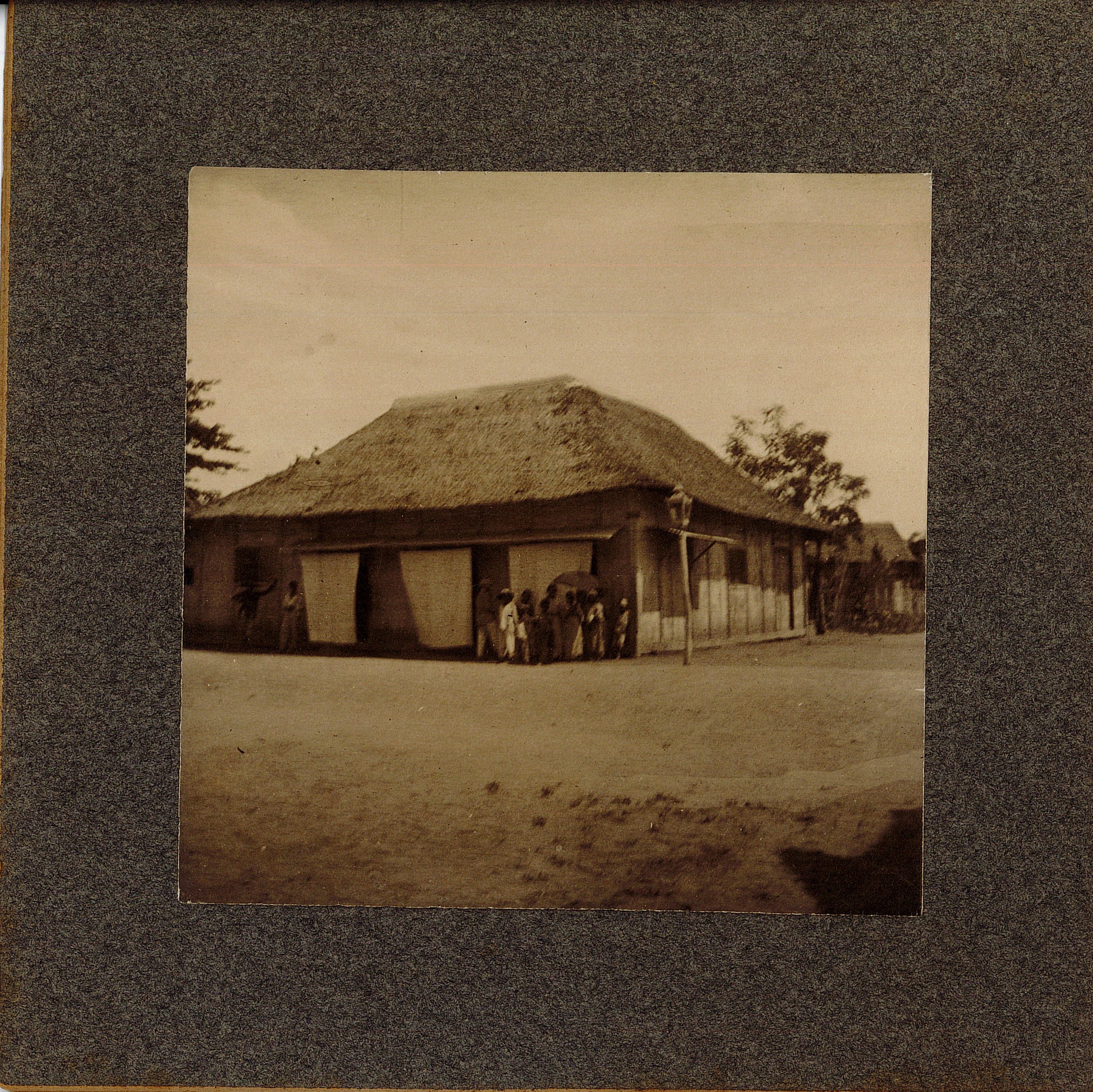

Along with the rest of the Thomasites, Gladwin and Lyman sailed out of San Francisco on July 23, 1901. At Pier 12 on the wharf waving goodbye to them was another former Rollins student, Henry B. Mowbray, who was transferred to the Pacific School of Religion in Berkeley, California, in 1900. Finally, after stopping in Honolulu on August 2, USAT Thomas reached Manila on August 21, 1901. After a two-day quarantine and disembarking on August 23, all Thomasites were reminded that they were “teachers of English and not missionaries,” serving as representatives of American values “by manner and morals we may be an example.”13 Gladwin soon received her assignment, but due to logistic challenges, it took her several more weeks to travel to Leyte, an island province in the Philippines’ Eastern Visayas region, to start teaching in fall 1901. Her school in Carigara enrolled 350 children with five Filipino teachers, three men and two women. Though her primary subject was English, she also taught geography, history, and arithmetic. Gladwin’s main responsibility was 200 girls in school, and based on her observation, these “dark-skinned, black-eyed creatures are anxious to learn.”14 However, her enthusiasm was soon dampened. In her writing dated January 20, 1902, she noted, “The work is terribly discouraging at times. Just now it seems as if my girls were learning nothing…”15 She was also frustrated by the poor condition of the schoolhouse. One day while teaching, she stepped on a loose board on the classroom floor and nearly went down. At the end of her first school year in the Philippines, Gladwin got a summer post in a normal school in Palo, Leyte, in May 1902, and then a new teaching appointment in Tanauan, Batangas, in August 1902. She noted that in her classroom there were a dozen desks, but 53 little tots were “so delighted to sit in them if only a short time to write their lessons.”16 Her situation finally improved when she was assigned to another public school in Palo, Leyte, in January 1903.

For a girl growing up in America, life in the Philippines presented its challenges of living in the tropical climate. In a letter to her parents dated October 21, 1901, Gladwin described an eye-opening experience of witnessing an immense, foot-long lizard swallowing a 7- or 8-inch-long centipede in her room.17 In another letter on Ash Wednesday, February 12, 1902, she noted, “Two things I should hate to do here, to die and to be buried here, and to be married. Neither of which I should do if it can be avoided.”18 After an 18-year-old girl died of consumption, she wrote in her diary that “I am beginning to think of home and the scent of orange blossoms.”19 A few days later, she recorded another startling incident of a peeping Tom and attempted thief right by her bedroom window.20 To cope with stress, she paid 50 cents in pesos for a pet monkey, but the real reprieve came from her East Asian trip of 1903. Instead of teaching in a summer school as in the previous year, Gladwin first visited the British colony of Hong Kong on May 10 and afterwards toured the Shanghai Bund. She then went sightseeing in Nagasaki on May 12, Kobe on May 18, and Tokyo on May 25, 1903. After her China-Japan excursion, Susan came back to Palo, Leyte, on July 26, 1903, revitalized, and when the new school year started on August 3, 1903, she had 55 students in her class in a public school with 221 children enrolled.

Diseases and mental health were also constant challenges faced by all Thomasites. Even before the group reached the Philippines, Gladwin’s cabin server from Memphis, Tennessee, aboard USAT Thomas died of typhoid or malarial fever on August 18, 1901. Upon arrival, many American teachers also experienced dysentery and horrible cramps.21 In September 1902, B. M. Sullivan, a graduate of Erskine College from South Carolina, was sent home due to tuberculosis.22 Mary Bynum from Mississippi was also sent home for health reasons, as were the McClellan sisters.23 In her letters, there were multiple references to cholera and dengue fever, and Gladwin caught dengue three times in five months. However, by taking dengue powder she bought from a drugstore in Manila, Susan was able to overcome the viral infection passed by mosquitoes and managed to stay on teaching.24 In addition, in her writings, she also described several experiences of living through earthquakes in the Philippines.

Gladwin’s letters and diaries also actively reflect the larger social and political situations and civil unrest of the new American colony in Southeast Asia at the beginning of the twentieth century. In her diary, she recorded a surprise attack by a band of 150 knife-waving bolo men on September 28, 1901, in which a group of soldiers were killed in Balangiga, six miles from her residence.25 In October 1901, due to military operations to suppress the insurrection on Samar, Gladwin and her American colleague had to evacuate from their teaching posts in Tacloban.26 In the guerrilla warfare where occasional gunfire was heard, she described how one naval officer was boloed by rebels hidden on shore.27 When Joseph R. Nedeau, a young inspector attached to the Maccabee Scouts, was killed in action, the US Army had to borrow an American flag and Gladwin’s prayer book to give a proper military funeral in Carigara.28 More dreadfully, in August 1902, three American teachers from McClellan, New York, were tragically murdered and a fourth one tortured in Cebu, in the Central Visayas region of the Philippines, a couple of whom Gladwin knew intimately.29 In her letter of November 30, 1902, she also described troubles with “ladrones,” who according to Susan were “murders and robberies all through the islands.”30 After some Americans were captured and murdered, the civil government passed stringent laws that forced local Filipinos living in the mountains to relocate into towns and offered rewards for the information and arrest of outlaws. Then on November 23, 1902, the Post Office in Tacloban was robbed, leading to the loss of $27,000 in soldiers’ salary payments.31 Gladwin also noted that some U.S. transports had carried out illegal smuggling activities, and the desertion of two American officers, who joined a group of 35 Filipino pirates in Misamis, Mindanao.32 In addition, an American deserter allegedly led a band of 12 rebels with guns in raiding Capucan, four miles away from Carigara where Gladwin resided and taught.33

Similarly, besides social tensions, Gladwin’s travel writings also recorded the rich traditions and cultural practices in the Philippines. Since the archipelago had served as a Spanish colony for several centuries, upon arrival, Susan quickly noticed the European influence and the presence of Mexicans in the Philippines. While passing through Luneta, one of Manila’s most iconic landmarks, she observed seven or eight cockfights and many Filipinos with roosters under their arms going to and from cockpits.34 She also witnessed several other cockfights in Malabon, where fast and furious bidding went to 1,500 pesos and up per game.35 For entertainment, Gladwin enjoyed a circus performance given by Filipinos during the holiday break of 1901-02; but attending a wedding party turned out to be a richer cultural learning experience for Susan, who was invited by her student to her sister’s marriage ceremony, which she described in detail to her parents.36 Some of Gladwin’s Filipino students later became her good friends in the Philippines; one of them, Aproniana Tomista, even followed Susan’s steps and became a teacher of English in Carigara.37 In early February 1902, Gladwin also observed how local Chinese celebrated the lunar new year and participated in another elaborate nuptial that mixed Visayan and Spanish cultural conventions.38 In addition, she was thoroughly impressed by Filipinos’ passion for fiesta celebrations, which typically started with large gatherings in the city plaza before sunset, and included long lines of floats and parades of bands and cheerful choruses.39 Moreover, during her teaching years in Southeast Asia, Gladwin developed close friendships with Alice M. Hollister of Michigan and W. W. Marquardt of Ohio, both fellow teachers assigned to Tanauan, Leyte. She helped with their marriage ceremony in Palo, Leyte, on December 26, 1902, and witnessed the birth of their first baby boy named Hollister.40 The Marquardts actually stayed in the Philippines for the next forty years until the outbreak of World War II in 1941.41

After two years living in the archipelago, Gladwin also sensed a rising resentment among locals toward Americans in the Philippines. “There is some force at work among the people, all anti-American. We see it here too. There is an entirely different attitude toward us since we came back.”42 She noted that, like people in other parts of the world, some well-to-do families sent their children to private schools. “So many of my girls are at work in the semester. The better class or the wealthy families do not send their girls to public school.”43 Many of those private schools in the Philippines were run by Catholic churches, which Gladwin did not hold in high regard. “Most of these padres have been trained by the Spanish priests and Friars. They an immoral lot most of them. Some have their women and children living with them in the conventos patterning after the Spanish priests, not very good examples for the people.”44 Not helping the matter was the fact that Filipino teachers only made a fraction of what American teachers earned in compensation. In 1903, while Susan received a $15 raise in monthly pay, native teachers were paid eight pesos or four dollars total.45 Exhausted and homesick, after teaching in Palo for the fall 1903 semester, Gladwin received her last teaching appointment in the Philippines, when she was appointed as matron with two prep classes in a newly opened local high school in January 1904, a post she held until her sailing from Manila to New York on June 17, 1904.46

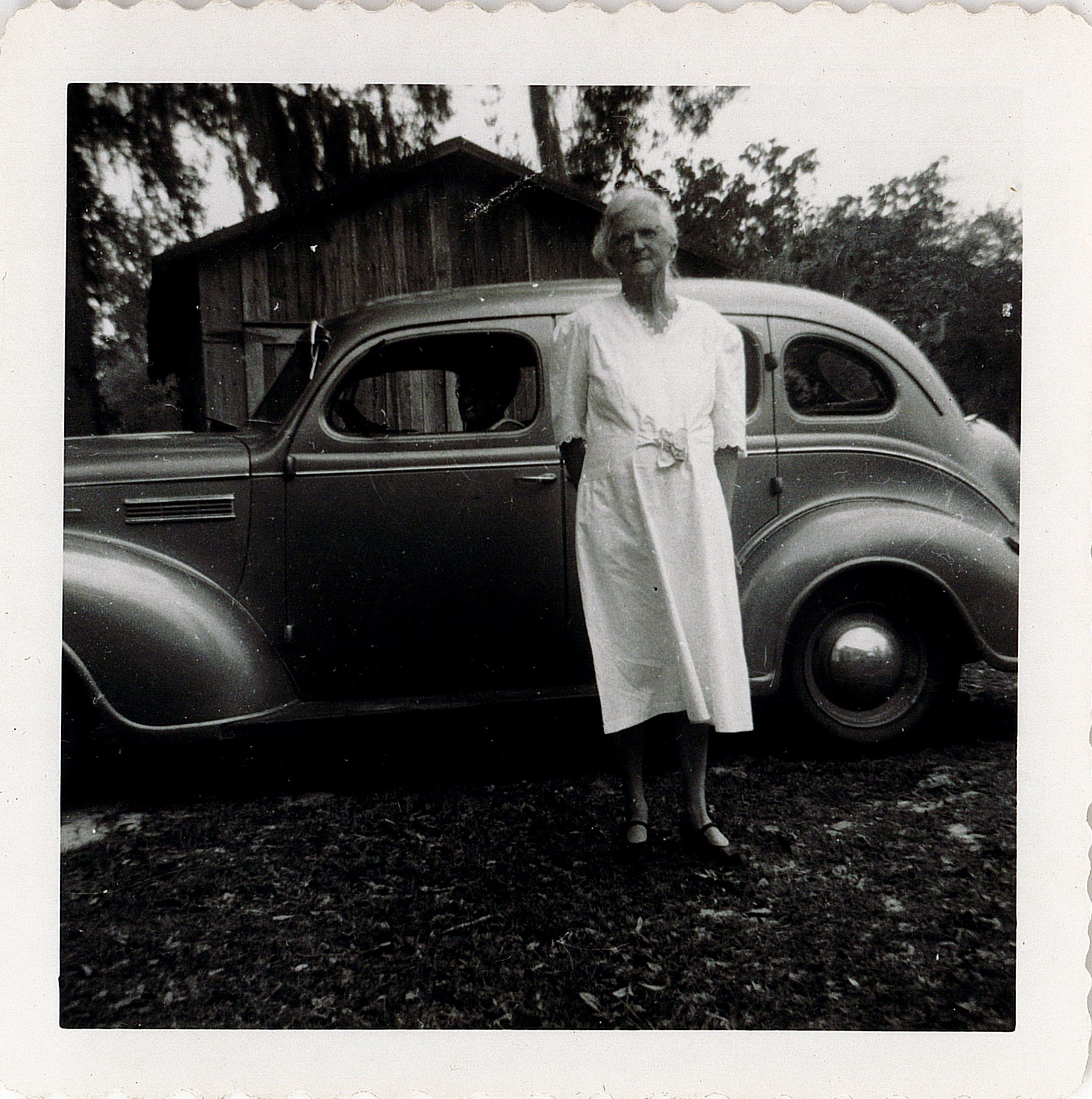

Upon returning from the Philippines, Gladwin resumed her education career in America. After a short, one-year stint teaching in Central Mercedes, Cuba, she served as a public-school teacher for multiple years in Florida, including at Fort Pierce High School. In 1915, she returned to Rollins to teach Spanish while serving as director of the Sub-Preparatory Department of the College. She served as a Spanish instructor while also teaching science and history in the Rollins Academy until her retirement in 1927. Throughout her life, she remained interested in the Philippines. On March 18, 1916, she wrote an article to introduce members of the Rollins academic community to the business development of the archipelago in Southeast Asia.47 After her retirement in Hawthorne, Florida, Susan maintained regular contact with the Rollins Alumni Office and regularly gave support to her alma mater in the 1930s and 1940s. On June 22, 1952, at age 78, Gladwin passed away in Fort Pierce and was later buried in Titusville, Florida. Four years later, to preserve and honor the works of her aunt, Susan Gladwin’s niece Margaret Enns donated her Letters from the Philippines 1901-1904 to the Rollins College Archives & Special Collections at Olin Library.

Endnotes

- “Susan Tyler Gladwin, Bleecker/Wisdom Family Tree.” Ancestry Library. ↩︎

- “Friends in Council,” Rollins Sandspur, December 22, 1896. http://stars.library.ucf.edu/cfm-sandspur/2332. ↩︎

- Rollins Tomokan 1917, Rollins College, Winter Park, Florida. https://scholarship.rollins.edu/tomokan/12/. ↩︎

- Susan Gladwin, “A Southern Home,” Rollins Sandspur, December 20, 1897, 2-3. ↩︎

- “Commencement Exercises for the Year 1899 Brought to a Close. Bright Outlook for the Coming Session.” Florida Times-Union and Citizen, May 26, 1899, 2. ↩︎

- Act No. 74: An Act Establishing a Department of Public Instruction in the Philippine Islands… January 21, 1901. Supreme Court E-Library, https://elibrary.judiciary.gov.ph/thebookshelf/showdocs/28/15605. ↩︎

- Susan Gladwin, “Jacksonville, Fla., July 16, 1901.” Letters from the Philippines 1901-1904, 7. Rollins College Archives, Winter Park, Florida. ↩︎

- Jonathan Zimmerman, Innocents Abroad: American Teachers in the American Century. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2006; Patrick M. Kirkwood, “‘Michigan Men’ in the Philippines and the Limits of Self-Determination in the Progressive Era,” The Michigan Historical Review 40:2 (2014): 63–86. doi:10.1353/mhr.2014.0039. ↩︎

- “National Archives and Records Service to A. J. Hanna, August 10, 1961.” 45E Susan Gladwin Alumna File, Rollins College Archives, Winter Park, Florida. ↩︎

- Ibid. ↩︎

- Ibid. ↩︎

- William Byron Hathaway, “Letters from Manila,” New Smyrna Breeze, January 10, 1902, to March 1903. 45E William Hathaway Alumni File, Rollins College Archives, Winter Park, Florida. ↩︎

- Gladwin, “Manila, P. I., September 1, 1901.” Letters from the Philippines 1901-1904, 33; “Manila, P. I., August 27, 1901,” 30. ↩︎

- Gladwin, “Carigara, Leyte, October 21, 1901.” Letters from the Philippines 1901-1904, 55. [15] Gladwin, “January 20, 1902.” Letters from the Philippines 1901-1904, 85. ↩︎

- Gladwin, “January 20, 1902.” Letters from the Philippines 1901-1904, 85. ↩︎

- Gladwin, “Tanauan, Leyte, P.I., August 24, 1902.” Letters from the Philippines 1901-1904, 150. ↩︎

- Gladwin, “Carigara, Leyte, October 21, 1901.” Letters from the Philippines 1901-1904, 56. [18] Gladwin, “February 12, 1902, Ash Wednesday.” Letters from the Philippines 1901-1904, 96. [19] Gladwin, “February 20, 1902.” Letters from the Philippines 1901-1904, 98. ↩︎

- Gladwin, “February 12, 1902, Ash Wednesday.” Letters from the Philippines 1901-1904, 96. ↩︎

- Gladwin, “February 20, 1902.” Letters from the Philippines 1901-1904, 98. ↩︎

- Gladwin, “March 2, 1902.” Letters from the Philippines 1901-1904, 104. ↩︎

- Gladwin, “Manila, P. I., August 30, 1901.” Letters from the Philippines 1901-1904, 30. ↩︎

- Gladwin, “September 14, 1902.” Letters from the Philippines 1901-1904, 155. ↩︎

- Gladwin, “Carigara, Leyte, March 16, 1902.” Letters from the Philippines 1901-1904, 107. ↩︎

- Gladwin, “Palo, Leyte, January 11, 1903.” Letters from the Philippines 1901-1904, 179. ↩︎

- Gladwin, “Sunday, September 29, 1901.” Letters from the Philippines 1901-1904, 46. ↩︎

- Gladwin, “Sunday, October 28, 1901.” Letters from the Philippines 1901-1904, 61. ↩︎

- Gladwin, “Carigara, Leyte, November 17, 1901.” Letters from the Philippines 1901-1904, 57. ↩︎

- Gladwin, “Sunday, April 13, 1902.” Letters from the Philippines 1901-1904, 116. ↩︎

- Gladwin, “Tanauan, Leyte, P. I., August 31, 1902.” Letters from the Philippines 1901-1904, 152. ↩︎

- Gladwin, “Tanauan, November 30, 1902.” Letters from the Philippines 1901-1904, 170. ↩︎

- Ibid., 171. ↩︎

- Gladwin, “October 4, 1903.” Letters from the Philippines 1901-1904, 230. ↩︎

- Gladwin, “Carigara, January 17, 1902.” Letters from the Philippines 1901-1904, 82. ↩︎

- Gladwin, “Manila, P. I., August 27, 1901.” Letters from the Philippines 1901-1904, 29. ↩︎

- Gladwin, “Manila, P. I., September 13, 1901.” Letters from the Philippines 1901-1904, 38. ↩︎

- Gladwin, “February 1, 1902.” Letters from the Philippines 1901-1904, 87-88. ↩︎

- Ibid., 89. ↩︎

- Gladwin, “February 8 & 10, 1902.” Letters from the Philippines 1901-1904, 92-93. ↩︎

- Gladwin, “Carigara, Leyte. March 30, Easter Sunday, 1902.” Letters from the Philippines 1901-1904, 111-112. ↩︎

- [40] Gladwin, “Palo, Leyte, December 26, 1902.” Letters from the Philippines 1901-1904, 176-178. ↩︎

- Elisabeth M. Hittreim, Teaching Empire: Native Americans, Filipinos, and US Imperial Education, 1879-1918. Lawrence: University of Kansas, 2019, 225. ↩︎

- Gladwin, “August 16, 1903.” Letters from the Philippines 1901-1904, 222-223. ↩︎

- Gladwin, “Carigara, Leyte. February 11, 1902.” Letters from the Philippines 1901-1904, 94. [44] Gladwin, “August 16, 1903.” Letters from the Philippines 1901-1904, 223. ↩︎

- Gladwin, “August 16, 1903.” Letters from the Philippines 1901-1904, 223. ↩︎

- Gladwin, “August 30, 1903.” Letters from the Philippines 1901-1904, 225; “November 15, 1903,” 233. ↩︎

- Gladwin, “January 31, 1904.” Letters from the Philippines 1901-1904, 240; “Manila, P. I. June 17, 1904,” 254. ↩︎

- Susan Gladwin, “Industries of the Philippines,” Rollins Sandspur, March 18, 1916, 3 & 5. https://stars.library.ucf.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=3373&context=cfm-sandspur. ↩︎