Written by Liam Taylor King

Southern liberal arts colleges like Rollins were indelibly shaped by whiteness.

Rollins and other liberal arts colleges in this period were strictly populated by model white students and cultivated a conception of the liberal arts that was dogmatically white. As evidenced by the difficulty of early Black Rollins students in the social sphere, the campus itself was socially white. Rollins did not place an institutional priority on diversity until the 1970s and did not develop any Black Studies program until the 1980s. Ultimately, the development of Black Studies at Rollins involved a coordinated partnership between students and faculty and depended on a significant change in the institution’s understanding of the liberal arts.

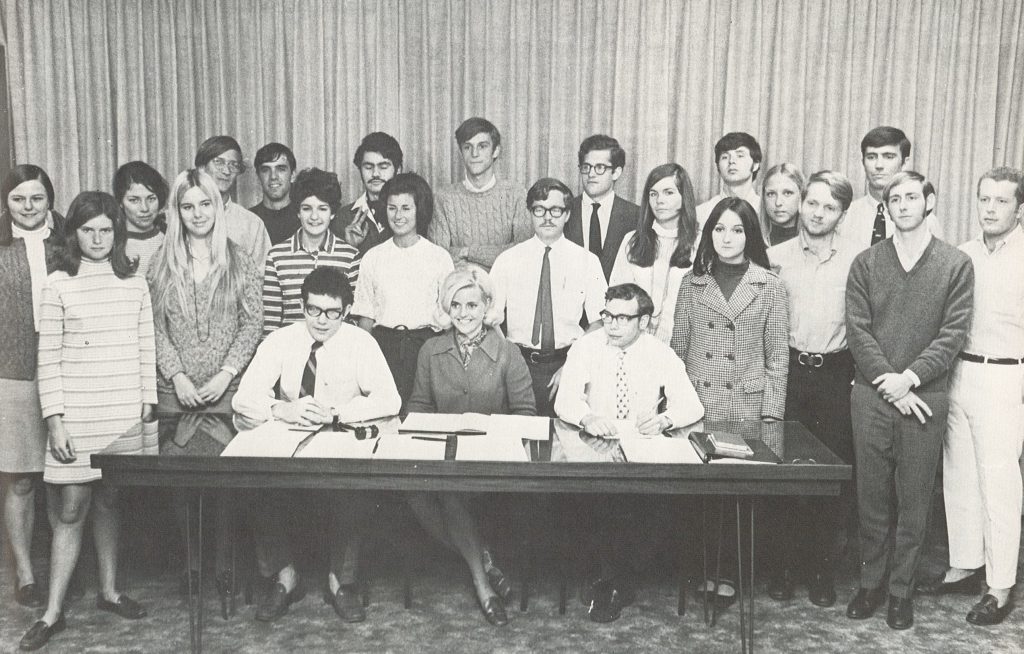

Early student efforts to get Black subjects and scholars into Rollins’ curricula began in 1969. In February 1969, Rollins freshman Gil Klein—a white student—attended the National Student Association “Conference on the University and Racism” in Atlanta, Georgia on behalf of the Rollins student government.1 Klein reported for the Sandspur, “It has become quite apparent that many students [at Rollins], perhaps even a majority, have little knowledge of what the unrest is all about and what the actual background of the Negro revolution is … It therefore appears to be quite necessary for Rollins to create a small black studies program. … These courses should be taught by a Negro professor.”2 What Klein did not report in his article, though, was that the 1969 “Conference on the University and Racism” was host to a major Black student protest. Tired of institutional racism within National Student Association, as well as in response to the revelation that the organization was CIA-funded, Black conference attendees published a resolution condemning the National Student Association and founded an organization of their own—the Student Organization for Black Unity.3 That Klein omitted this detail revealed him to be no fierce radical. Instead, Klein might be considered a moderate. His membership in the Student Government indicated an underlying respect for institutionalism. One of the first voices, then, for Black studies at Rollins was not a Black Panther but a white moderate.

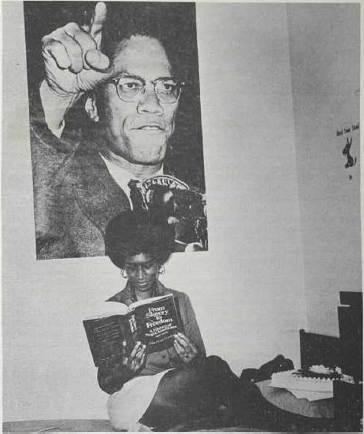

The next major student voice to call for Black studies at Rollins was Theda James. The March 13, 1972 issue of The Sandspur was devoted entirely to Black students at Rollins and contained an article by James—then a sophomore—entitled, “The Role of Black Studies in Education.” James’ perspective was far more radical than Klein’s, and she saw a purpose to Black Studies education far different than what Klein envisioned. Where Klein saw a “small Black Studies program” as primarily benefitting the ignorant and naïve white students of Rollins, James saw the critical function of Black Studies that “Black folks may at last have the opportunity to reveal to the world the ‘true nature’ of the Black experience (i.e., what it means to be Black in a white racist society.)” James also believed a Black Studies curriculum would allow Black students to understand the “pathological conditions of white Americans.” James’ proposal for a Black Studies curriculum carries a single significant demand, shared by Klein: that the professors for Black Studies at Rollins be Black. In response to the concept of white professors teaching Black Studies courses, James wrote, “My sentiments on this question are absolutely negative—no—nah!!!”

In the later history of the Black Studies program at Rollins, the race of faculty becomes an interesting site of change over time. Concluding her article, James did ultimately conclude a third purpose for a Black Studies curriculum at Rollins: “It will perhaps serve to enlighten confused naïve white students.”4

At this time in Rollins’ history, Black voices on campus were remarkably few. The first Black student to attend Rollins college, John Mark Cox, Jr., enrolled in 1964, and five years later the Rollins Black Student Union was founded.5 The social atmosphere of Rollins was by no means integrated by the 1970s, however. In 1977 two Rollins students published a comment in the Sandspur which read, “In 1965 Rollins first opened its doors to Black students, and over the past twelve years Rollins has done nothing much greater than opened its doors.”6 It was in this milieu that the struggle for Black Studies curricula which occurred at Rollins thus took shape, organized by Black students who felt themselves socially excluded.

The presidency of Jack Critchfield from 1969 to 1978 was wrought with budgetary crisis.7 Indicative of the country’s financial stress, Sandspur articles ran U.S. Department of Energy public service announcements advising students to conserve fuel.8 Nevertheless, student-led efforts to establish a Black Studies persisted. In 1974, Roxwell Robinson, then-President of BSU, sent a letter to President Critchfield requesting the assurance of “at least three Black Culture courses in an academic year,” including “at least two literature courses and at least one history course.”9 Robinson’s concern was that the College would cut Black Studies courses as a budgetary maneuver. Critchfield was unable to make such a promise, stating that “it is my intent to continue Black Culture in the future” but that “if economic conditions become so disasterous [sic] that many actions that are currently not contemplated become necessary, the entire curriculum offerings would have to be evaluated accordingly.”10 Critchfield’s unwillingness to make Black Studies a protected priority of the college indicated both the severity of Rollins’ economic uncertainty as well as an institutional mission which neglected to prioritize the social identities of Rollins students.

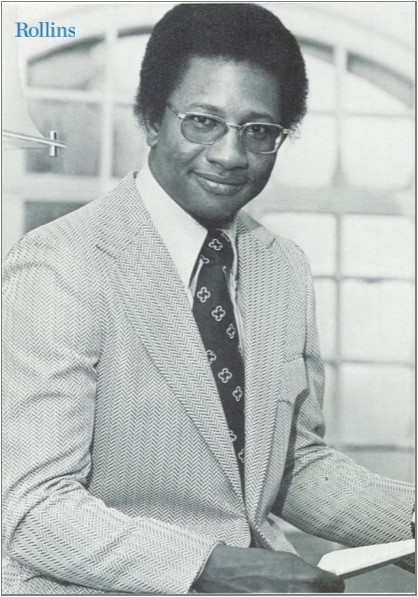

Critchfield’s presidency thus struggled to deliver on demands for institutional change. The primarily white faculty could hardly be said to be capable of teaching Black Studies in the manner envisioned by James (or even Klein for that matter). But for one figure, the Critchfield era could not be said to have made any significant contribution to Rollins’ pathway of diversity. This figure, who radically impacted the course of racial diversity at Rollins, was Alzo Reddick. Reddick began at Rollins in 1971, teaching in the history department (at that time “history and public affairs”) and serving as Assistant Dean of Student Affairs.11 Reddick authored a memorandum in May 1972 on the Southern Regional Educational Board Conference on Minority Students which he had attended. Therein Reddick made two recommendations: first, that Rollins continue recruiting equals amounts of minority students from junior colleges as from secondary schools; and second, that “attempts be made to create as comfortable an atmosphere as possible for minority students.”12 In the fall semester of 1977, Reddick taught “H271: Afro-American History,” for which the course description read in part, “The course endeavors to read Afro-American history from a Black perspective rather than from outside Black America.”13 At long last, Rollins had a single course in Black Studies taught by a Black professor. But in 1977, Jack Critchfield announced his resignation, and the era that followed proved monumental for Black Studies and diversity at Rollins.

With the appointment of President Thaddeus Seymour in 1978, Rollins’ campus became the site of a battlefield for the liberal arts. In fact, Seymour spent much of his first year as President drumming up esprit for liberal education. In 1979, the Rollins faculty ratified a new set of institutional mission statements. Importantly, amid various platitudinal statements on liberal education, an emphasis on diversity shone through. The text read, “The educational experience at a college is enriched when the student body is diversified culturally, economically, racially and by interests and talents.”14

Two articles published in the Sandspur in 1978 demonstrated the new campus vim. The first was published in May 1978 by professor of English Alan Nordstrom, entitled “Liberal Arts Concerned with Quality.” In it, Dr. Nordstrom expressed a perspective on the liberal arts which took aim at the developing trend of livelihood-focused instruction for undergraduates. Nordstrom wrote, “The central concern of a liberal education is with the quality of one’s life, not with the source of one’s livelihood.”15 Nordstrom’s article can also be read as an indictment of the just-ended Critchfield presidency, in which a new major in Business quickly grew to swamp most other disciplines.16

At the beginning of the fall 1978 semester, in fact, Rollins Dean of Education Daniel DeNicola gave an address which stated “there is only one profound motivation for education: to become a better person.”17 In response, student Jim Pendergast doubled down on Nordstrom’s original point: “Clearly, if we are to accept that as one definition of the liberal arts mission, then administrators must give serious and thorough consideration to the usefulleness [sic] of professionally or vocationally oriented majors here at Rollins.”18

Not long after Seymour’s presidency began, the zeal for classical liberal arts had not yet died. History professor Dr. Jack C. Lane in 1983 described Rollins and similar schools as “anachornisms,” wherein “what students really want … is a course of study that, with a little effort, will guarantee them an affluent existence in the life after Rollins.”19 Lane continued, “I’ve got news for them. There are no such courses, not even in business studies, where so many of them seem to be drifting.”20 In 1987, Lane authored an article in which he stated plainly, “many of the problems that have arisen at the college in the past decade can be traced directly or indirectly to the atrophy of community.”21 Rollins, Lane argued, was beset by “atomization,” which pervaded its curriculum in the form of academic minors. This particular article was penned only months after the implementation of a Black Studies minor at Rollins in May 1987.22 Not to suggest that Lane opposed a Black studies curricular—his other writings indicate the opposite—but he did clearly oppose the tendency of this new era in Rollins’ history to compartmentalize the liberal arts. Under Lane’s perspective, if the college wanted to prioritize diversity and inclusion, it should do so holistically.

The contest of educational ideologies at Rollins in fact signaled a rejection of contemporary trend. Rollins’ radical emphasis on the liberal arts in the 1980s marked a departure from practical forms of education which become national vogue in the 1980s. During this period, there was significant development of “skill-based” education in colleges and universities.23 Sociologist Stanley Aronowitz connected the increase in “practical” programs of higher education to the broader rise of neo-conservatism in U.S. politics.24 The fact that Rollins was engaged in the struggle for increased liberal arts, and the fact that the liberal arts ultimately carried the day, indicated institutional conviction and a willingness to reject contemporary trends.25 These two qualities would become necessary in the development of Rollins’ Black Studies curriculum.

One intriguing incident to occur at the very beginning of Seymour’s presidency which illustrates the new liberal educational ideology involved a school performance of Equus, a play in which a man loves a horse. In May 1979, the Rollins Theatre Department became the target of ire among the Winter Park and Orlando populations due to a scene in which two actors—one male, one female—appeared on stage completely nude. Outrage against the performance began with John Butler Book, a local fundamentalist Church of Christ preacher.26 Eventually the City of Winter Park itself attempted to enjoin the performance on account of a city ordinance which forbid “any person within the corporate limits of the city to be found in a state of nudity, or in a dress not belonging to his sex, or in an indecent exposure of his person.”27 Students rallied with fervor against the city’s action, especially after the play’s director, John Storer, was arrested on campus by an “armed, uniformed police officer.”28 Though Seymour opposed what the incident meant for freedom of expression on campus, he condemned students who became disorderly in their protest. Seymour said, “When somebody looks me in the eye, I want to say Rollins obeyed the law. I’ve spent too much of my life protecting orderly change.”29 Ultimately, the play was permitted to go on uninhibited by the City of Winter Park, and prosecutors eventually dropped the charges.30 The incident thus perfectly encapsulated Seymour’s presidential philosophy: institute liberal ideals while maintaining a moderate image.

A vast array of changes made under Seymour’s tenure demonstrate, at least superficially, the college’s doubling down on the liberal arts. In 1982, Rollins course catalogs now included the cognomens “a liberal arts college” beneath the school’s name. In the same year, the college changed the language in which diplomas were written from English to Latin. This presented the novel problem of how to properly parse “Winter Park” into Latin. Though it was generally agreed that there was no perfect translation, the college settled on hiberni viridarii, “pleasure-garden of winter.”31 Likewise, the Bachelor of Arts degree (B.A.) became the Artium Baccalaureus (A.B.).32 Latin became a symbol of this return to the liberal arts, with Rollins establishing a new Classics department in 1983.33 Additionally, in 1983, Rollins completed suspended its Business major, which was not only a symbolic gesture of returning to the idealized liberal arts embodied in faculty Sandspur columns, but a practical measure taken in response to the department’s organizational instability.34

On May 13, 1987, the Rollins College faculty approved a minor in “African/Afro-American Studies,” to be directed by Richard A. Lima, professor of French.35 In the fall of 1988, only one of three core courses for the minor was taught by a Black professor: Dr. Deidre Crumbley, visiting professor of anthropology.36 Interestingly, this new minor was added in the same year as another minor, in Irish Studies, which received much greater institutional support on account of the semester-in-Ireland program operated by Rollins.37 Just a few years earlier, Rollins had approved another interdisciplinary minor in Women’s Studies.38 This new smattering of minors represented the new liberal arts at Rollins—one in which discipline specification was not only permitted but encouraged, and interdisciplinarianism reigned supreme.

During the 1990s at Rollins, the Black Studies program was renamed to “African/African- American Studies” and found a new head in Manuel Vargas, professor of Anthropology. Of the four core courses for the minor in 1998, three were taught by Vargas, one, HIS247: Race in American History, was taught by white professor Gary Williams.39 In the late 1990s, it was impossible for a Rollins student to take a course in Black studies without having a Black instructor. This situation did not persist, however. From 2001 until 2022 with the hiring of Visiting Professor Dr. Ja’Nya Jenoch, students could feasibly complete the Africa/African-American Studies minor having never once interacted with a Black professor.40

In these post-Seymour years, Rollins once again drifted in educational ideology. In 1995, the cognomens was once again altered, this time to read “a comprehensive liberal arts college.”41 The ideal of “comprehensive” liberal arts could be read to mean “practical” liberal arts. Rollins had departed from the high-minded ideals of the Seymour period in favor of more grounded educational principles.

The history of Rollins College cannot be painted in broad strokes. As a predominantly white institution, it cannot be said to have made great strides in diversity since 1964, when the first Black student was admitted. Yet, it cannot also be said that the college has remained stagnant for the past fifty years. Ultimately, the story of the Black Studies program is the story of the college itself: one of effort and error, wherein the path to justice has never been clear. A historical study, then, of this period reveals what policies worked and what policies failed; this history gives insight to the destinations where certain paths lead as the college continues to evolve its mission and shift its values. The development of a Black Studies curriculum at Rollins coincided with a significant shift in the institution’s understanding of the liberal arts, and represented a powerful student-faculty coalition to cultivate diversity on the Rollins campus.

About the Author: Liam Taylor King is a Rollins college student majoring in History with a minor in Africa/African-American Studies. Liam is a member of the Bonner Leaders program at Rollins, wherein he has volunteered over five-hundred hours at the Holocaust Memorial Resource and Education Center. Liam is currently working on an honors thesis investigating queer histories local to Winter Park and Rollins. Outside of history, Liam is passionate about poetry. After Rollins, Liam hopes to attend law school and become an attorney.

1 Gil Klein, “Colleges Deal With Racism,” Sandspur, March 14, 1969; Tomokan 1969 (Winter Park: Rollins College), 82, 203.

2 Gil Klein, “Colleges Deal With Racism,” Sandspur, March 14, 1969.

3 Richard D. Benson II, “Black Student-Worker Revolution and Reparations: The National Association of Black Students, 1969-1972,” Phylon 54:1 (Summer 2017): 64.

4 Theda James, “The Role of Black Studies in Education,” Sandspur, March 13, 1972, 9.

5 Rachel Walton, “Pathway to Diversity – The History of Race Relations at Rollins: A Brief Overview from the Archives, Part Two (1951-Present),” From the Rollins Archives, Rollins College, February 26, 2021, https://blogs.rollins.edu/libraryarchives/2021/02/26/pathway-to-diversity-the-history-of-race-relations-at-rollins-a- brief-overview-from-the-archives-part-two-1951-present/.

6 Johnnie Williams and Gigi Morgan, “Students Comment on The Black Perspective,” Sandspur, November 4, 1977.

7 Jack Lane, Rollins College Centennial History: A Story of Perseverance 1885-1985 (Orlando: Story Farm, 2017), 176.

8 See Sandspur, May 11, 1977, 12.

9 Roxwell Robinson to Jack Critchfield, November 21, 1974, Rollins Digital Collections, accessed December 6, 2022, https://archives.rollins.edu/digital/collection/diversity/id/114/rec/51.

10 Jack Critchfield to Roxwell Robinson, November 26, 1974, Rollins Digital Collections, accessed December 6, 2022, https://archives.rollins.edu/digital/collection/diversity/id/113/rec/51.

11 Rollins College, Catalog Volume LXVI, 1971 (Winter Park: Rollins, 1971), 112.

12 Alzo J. Reddick, “Memorandum: Southern Regional Educational Board Conference on Minority Students,” Folder 1, Box 12, Black Student Union, Rollins College Archives & Special Collections, Olin Library, Winter Park, Florida (hereafter RCA).

13 Rollins College, Catalog Volume LXXI, 1977-79 (Winter Park: Rollins, 1977), 109.

14 “Some Propositions Regarding the Institutional Mission of Rollins College,” Rollins College Faculty Minutes 1987-88 1988-89, bound volume, RCA.

15 Alan Nordstrom, “Liberal Arts Concerned with Quality,” Sandspur, May 24, 1978, 4.

16 Nordstrom, “Liberal Arts Concerned with Quality.”

17 Jim Pendergast, “Definition of ‘Liberal Arts’ Determines Curriculum,” Sandspur, October 27, 1978, 2.

18 Pendergast, “Definition of ‘Liberal Arts’ Determines Curriculum,” 2.

19 Jack C. Lane, “Liberal Education,” Sandspur, December 13, 1983, 8.

20 Lane, “Liberal Education,” 8.

21 Jack C. Lane, “The Eclipse of Community at Rollins College: Some Consequences,” Sandspur 96:3 (1987): 10.

22 “Minutes, College of Arts & Sciences Faculty Meeting, May 13, 1987,” Folder 9, Box 9, Faculty Bylaws & Minutes, RCA.

23 Stanley Aronowitz, “Politics and Higher Education in the 1980’s,” The Journal of Education 162:3 (1980): 40-49.

24 Aronowitz, “Politics and Higher Education in the 1980’s,” 47.

25 This is not to say, of course, that Rollins was some progressive oasis during an otherwise conservative era. In fact, in the 1988 U.S. presidential election, a mock election of 281 Rollins voters revealed 71.9% of students favored Bush/Quayle over Dukakis/Bentsen, a percentage which weighed far more conservative than the national final of 53%. “Results of the Rollins Pulse/SGA Mock Election,” Rollins Pulse, October 26, 1988.

26 Randy Noles, “Naked Truth,” Winter Park Magazine (Spring 2020).

27 Listed as Sec. 18-14 in Winter Park Ordinances in Sharon Lacey, “Equus: Needless Controversy,” Sandspur, May 11, 1979; intriguingly, the U.S. Supreme Court had already decided in Miller v. California, 413 U.S. 15 (1973) that literary or artistic nudity was protected under the First Amendment, and thus the city was fighting a losing battle.

28 Noles, “Naked Truth.”

29 Lacey, “Equus: Needless Controversy.”

30 Noles, “Naked Truth.”

31 Laura Ost, “Latin Diploma Presents a Classic Problem,” Rollins Alumni Record 63:1 (February 1985): 23.

32 Ost, “Latin Diploma Presents a Classic Problem,” 23.

33 Arts & Sciences Faculty, “Minutes, College of Arts & Sciences Faculty Meeting, April 29, 1986,” Rollins Scholarship Online, April 29, 1986, https://scholarship.rollins.edu/as_fac/200/.

34 Arts & Sciences Faculty, “Minutes, College of Arts & Sciences Faculty Meeting, October 13, 1980,” Rollins Scholarship Online, October 13, 1980, https://scholarship.rollins.edu/as_fac/230/.

35 “Minutes, College of Arts & Sciences Faculty Meeting, May 13, 1987,” Folder 9, Box 9, Faculty Bylaws & Minutes, RCA.

36 Rollins College, Catalogue Volume LXXVII, 1988 (Winter Park: Rollins, 1988), 65.

37 Arts & Sciences Faculty, “Minutes, College of Arts & Sciences Faculty Meeting, May 13, 1987,” Rollins Scholarship Online, May 13, 1987, http://scholarship.rollins.edu/as_fac/214.

38 Arts & Sciences Faculty, “Minutes, College of Arts & Sciences Faculty Meeting, March 29, 1981,” Rollins Scholarship Online, March 29, 1981, https://scholarship.rollins.edu/as_fac/172/.

39 Rollins College, Catalog Volume LXXXVII, 1998 (Winter Park: Rollins, 1998).

40 See Rollins College, Catalog 2008, 2008, https://scholarship.rollins.edu/catalogs_liberalarts/169/.

41 Rollins College, Catalogue Volume LXXXV, 1995 (Winter Park: Rollins, 1994).