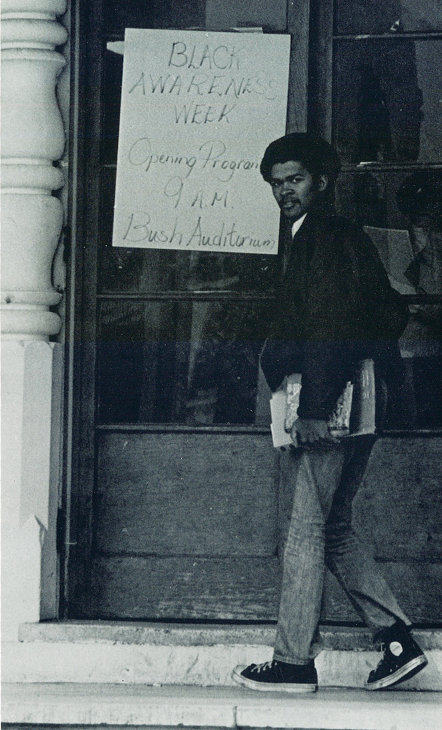

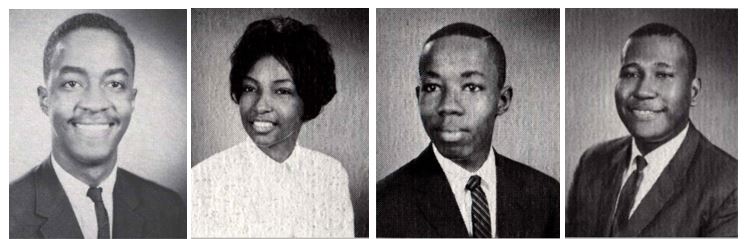

Rollins College officially desegregated when it welcomed its first African American student in 1964, John Cox (pictured further down the page). This year marked the beginning of a longer, and undoubtedly difficult, journey for black students at Rollins to find spaces they felt welcome on campus, enjoyed as full-time residents, and excelled as leaders.

Looking back, it is clear that some of these safe and familiar spaces included: the chapel (Knowles Memorial Chapel), the theater (Annie Russell Theater), the gymnasium (Alfond Sports Center), a few residence halls (for example, Ward Hall), campus green spaces (like Mills Lawn), the bookstore (Rice Family Bookstore), and of course, the classroom. African American students also seemed to “find their anchor” (to use a common, more current Rollins slogan) through various student organizations on campus such as Residential Life, Greek Life, the newly-formed Black Student Union, and performing arts groups like the Rollins Players.

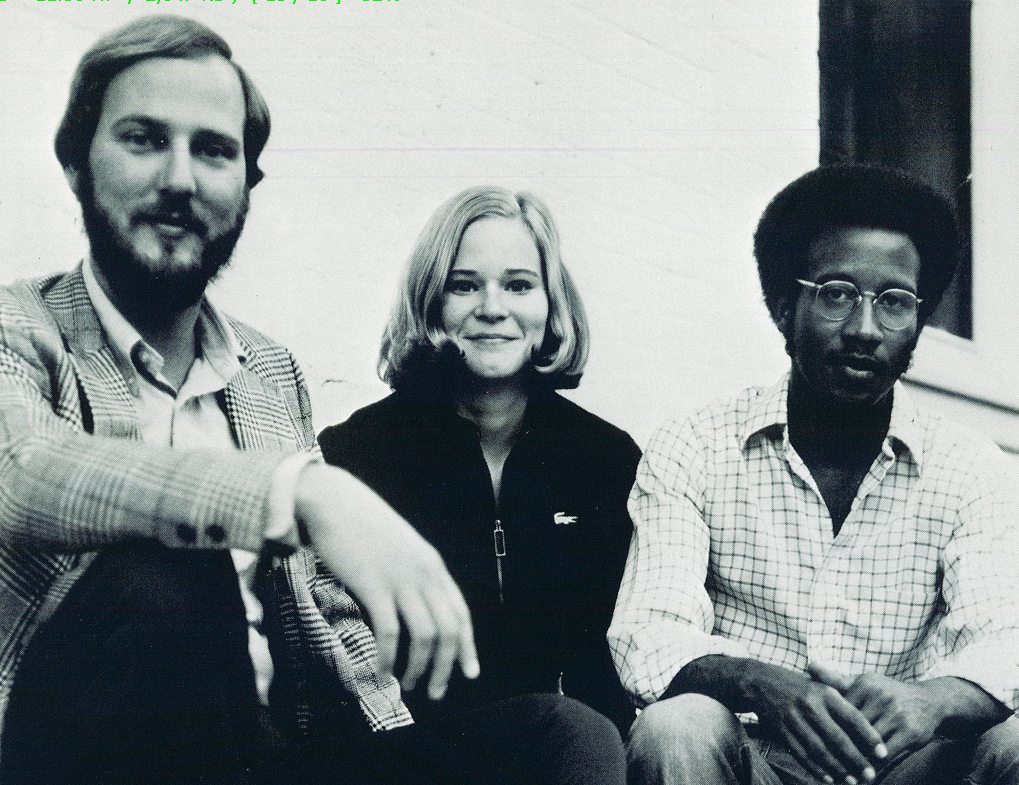

Early black students at Rollins explored these campus spaces and groups as individuals with unique backgrounds and circumstances, and like Rollins students today, they learned and grew alongside fellow students with similar interests and passions. However, these students made friends, experienced hardship and stress, did their schoolwork, and created their “home away from home” for four years on a campus that had never had an African American graduate. How this historical reality affected these students personally is very hard to say by just examining the archival record.

Early black students at Rollins explored these campus spaces and groups as individuals with unique backgrounds and circumstances, and like Rollins students today, they learned and grew alongside fellow students with similar interests and passions. However, these students made friends, experienced hardship and stress, did their schoolwork, and created their “home away from home” for four years on a campus that had never had an African American graduate. How this historical reality affected these students personally is very hard to say by just examining the archival record.

Lewanzer Lassiter, Bernard Myers, and William Johnson were the first black graduates of Rollins in 1970.

In the decades before 1970, Rollins had two campus buildings open to non-white community members including the Recreation Hall built in 1926 and Knowles Memorial Chapel dedicated in 1932. Importantly, for many decades before integration of the student body, Rollins employed black staff members and maintained close connections with leading black educational institutions in the state, like Bethune-Cookman University and the Hungerford Vocational School of Eatonville. While that scenario may have been a rarity in the Jim Crow Era, it is perhaps even more surprising to learn that some Rollins administrators were open to hosting and supporting the local African American community and its cultural events as early as the 1930s. This was made evident by Hamilton Holt’s decision in 1933 to allow the now-famous author and playwright, Zora Neale Hurston, to put on one of her first plays, From Sun to Sun, on campus grounds. The play was held in the Recreation Hall on the edge of campus with an all-black cast who performed for a white-only audience.

These snapshots of integrated Rollins buildings and spaces over the last century, and the people that experienced these realities, help to complicate Rollins’ involvement with campus and community race relations, especially in the historical context of a southern and racially divided town like Winter Park.

— Erin McFee (Class of 2019)