One of the particular strengths of the CFAM collection I have been delighted to discover is in the medium of etching, one of the primary modes of printmaking used by artists since the Renaissance. To make an etching, a very smooth copper plate is coated with an even layer of wax. The etcher then uses a specialized needle to scrape away the parts of the plate she wants printed. When the plate is ready it is submerged in a bath of acid, which will eat away at, or “bite,” the plate only where the lines have been drawn. The printmaker then cleans the plate, rolls ink onto it, wipes off the excess, and then uses a special press to transfer the ink from the lines onto a piece of paper. The printmaker can then make further refinements by reapplying the wax and repeating the whole process.

Though it takes practice and skill to master etching, the physical process itself is as easy as drawing with a pencil on paper and allows the artist a great deal of freedom in creating lines and shading, and is particularly well-suited to representing outdoor scenes.1 Etching was incredibly popular among Old Masters, and artists—perhaps most notable among them Rembrandt—used it to make money and circulate their artworks to wider publics. It had fallen somewhat out of favor by the middle of the nineteenth century, however, having been displaced by wood engraving, lithography, and photography.2

132 x 207 mm, Gift of Anthony Capodilup and Sandra M. Sommer, 2016.50

It was around this time that artists on both sides of the Atlantic, particularly in France, Britain, and the United States, began to rediscover the medium, which they saw as allowing for a greater freedom of artistic expression than merely mechanical reproductive processes like photography.3 One of the key figures in this revival was the American expatriate James McNeill Whistler, who brought his etching plates directly into the field, using them as he would pen and paper to capture the transient effects of light and water in his explorations of his beloved Thames.4 CFAM owns two of his Thames etchings, both produced in 1879, at a moment when he was in financial distress after years of lavish spending and a financially disastrous libel lawsuit he had pursued against the critic John Ruskin.5 These prints, which show the last of the old wooden bridges on the Thames, had a strong nostalgic appeal for Londoners, and helped Whistler recover his financial bearings. At the same time, works like Little Putney Bridge are prime examples of Whistler’s atmospheric aesthetic. This print, in particular, gives much of its space over to the river itself, which Whistler has represented with a relatively small number of bold, economical lines. His butterfly monogram, visible in the lower right, asserts his artistic presence in—and mastery over—the scene.

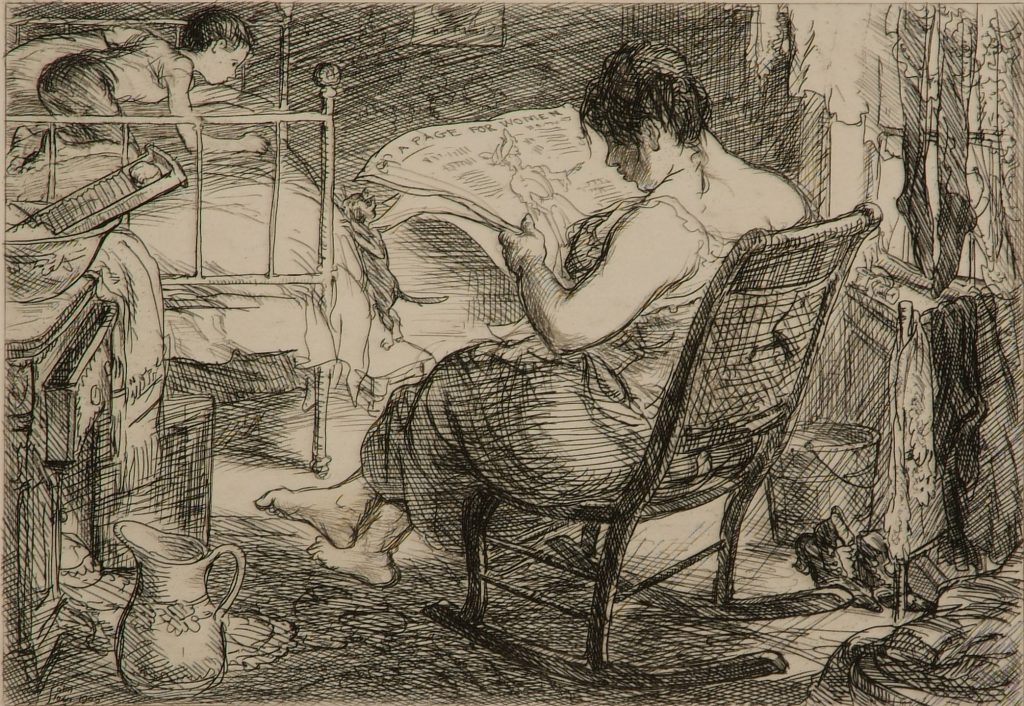

Etching continued to be popular throughout the end of the nineteenth century and the beginning of the twentieth, and CFAM holds a number of important etchings by American artists. To end this blog post, I would like to examine one of my favorites, John Sloan’s 1905 etching The Women’s Page, part of his New York City Life series, which showed scenes of everyday life—mostly in his working-class Manhattan neighborhood. Etching was appealing to Sloan and his colleagues in the Ashcan School for the same reasons it had first appealed to Whistler: it was a handmade, artist-focused medium with a robust history that also allowed for relatively fast production.6 Yet Sloan’s interior scene looks nothing like Whistler’s landscape, indicating just how different the two artists approached the medium. Whistler was the aesthete par excellence, emphasizing the pure pictorial qualities of his subjects. Sloan, on the other hand, came from the world of commercial newspaper illustration, and was interested in depicting the lives of everyday New Yorkers.7 The Women’s Page shows a woman enjoying a respite from her day while her young son plays with the cat on her bed. I like it because it eschews the idealized depictions of femininity that had been so common in the history of art in favor of something that feels more truthful.8 Plus, it’s a masterclass of the medium, alternating dense crosshatching with areas of pure white paper to not so much outline forms as building them up. It’s quite a contrast with Whistler’s sparse linework, and the comparison of the two works shows all the possibilities of etching as a medium.

1Shannon Vittoria, “Nature and Nostalgia in the Art of Mary Nimmo Moran (1842-1899)” (Doctoral Dissertation, New York, NY, Graduate Center, City University of New York, 2016), 106.

2Vittoria, 108.

3Vittoria, 112.

4Margaret F MacDonald et al., An American in London: Whistler and the Thames, 2013, 16.

5For more on the Whistler-Ruskin trial, one of the most celebrated incidents in the history of modern art, see Linda Merrill, A Pot of Paint : Whistler v. Ruskin (Washington : Smithsonian Institution Press in association with the Freer Gallery of Art, Smithsonian Institution, 1992), http://archive.org/details/potofpaintwhistl00merr.

6Michael Lobel, John Sloan: Drawing on Illustration (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2014), 51.

7For an in-depth overview of the influence of Sloan’s illustration on his work as a printmaker and painter, see Lobel, John Sloan.

8For an excellent analysis of this print in the context of such idealized depictions, in particular the illustrations of Charles Dana Gibson, see John Fagg, “Clutter and Matter in John Sloan’s Graphic Art: Clutter and Matter in John Sloan’s Graphic Art,” American Art 29, no. 3 (2015): 28–57, https://doi.org/10.1086/684919.