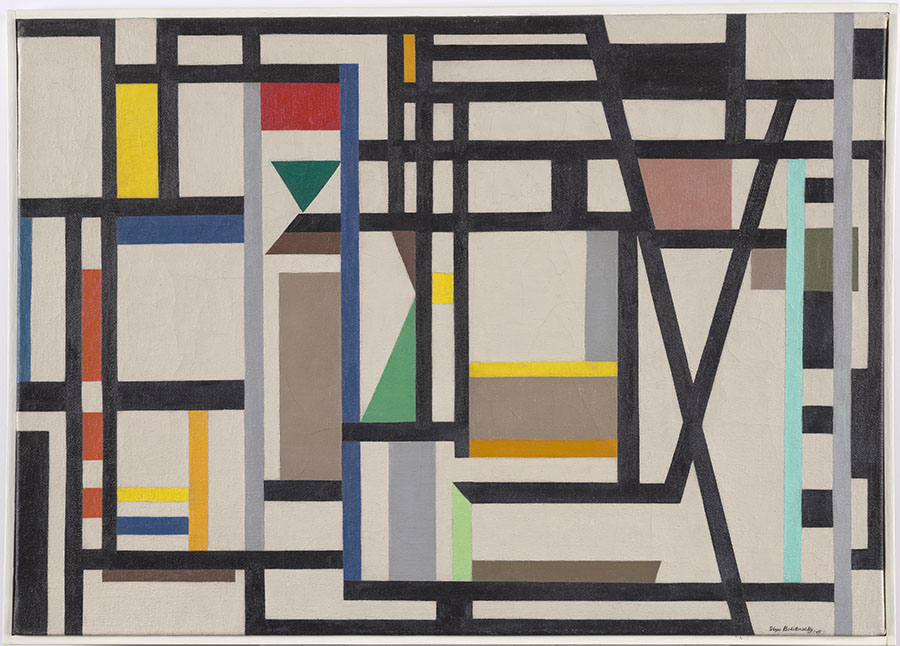

Recently, while conducting research on the painter Elizabeth Murray (herself worthy of a future blog post), I came across an interesting anecdote. In 1994 Kirk Varnedoe, the Museum of Modern Art’s Chief Curator of Painting, asked Murray to curate an exhibition from MoMA’s extensive permanent collection. Reflecting on the experience, Murray marveled at the sheer quantity of works in that collection that had fallen nearly out of historical memory, remarking “…what I didn’t know I’d get out if it when I started…was how fast people come and go. How fast they are forgotten. The men too. There were hundreds of [Pavel] Tchelitchews; hundreds of works by Ilya Bolotowsky.”1 This quote immediately made me think of CFAM’s own work by Bolotowsky, characteristically entitled Abstraction, which I researched earlier this year. Indeed, Murray’s words made me think of one of the most interesting themes that has emerged during my year working on this project: the ways in which changing artistic tastes have worked to obscure the often-complex history of American modernism.

Most readers will probably be familiar with what is often regarded as the canonical story of modernism. It’s a story that the Museum of Modern Art itself had much to do with establishing. In this story, Paris is the center of the modern art world from the birth of Impressionism to World War II, when the disjunction caused by the war and Nazi atrocities, as well as the new cultural and economic role assumed by the United States, caused the art world’s center of gravity to shift to New York. In New York, a group of American painters—exemplified by Willem de Kooning—adapted certain aspects of European avant-garde painting with a quintessentially swaggering, American individualism, to create Abstract Expressionism. The lithograph Two Women, part of the CFAM collection, exemplifies de Kooning’s slashing, even brutal gesture, the way in which he seems to insist upon the image’s existence as a record of his own body’s movements. In recent decades scholars have been reconsidering this narrative, exploring the ways in which it leaves out other figures, including those who were influential or popular in their own time but, for various reasons, were not appealing to critics and collectors of later generations. Ilya Bolotowsky was one such figure, as was his colleague George L. K. Morris.2

In one sense, the two men could not have been more different. Bolotowsky was born to Russian Jewish parents in St. Petersburg, immigrating with his family to the United States in 1923, part of a great wave of Russians of Jewish descent fleeing the country.3 Morris, on the other hand, counted as ancestors Lewis Morris, a signer of the Declaration of Independence; Gouveurneur Morris, who wrote the Preamble to the Constitution; and New York’s Schermerhorn family. He was wealthy, urbane, and patrician, unlike the working-class Bolotowsky.4 What brought the two men together, however, was a fierce commitment to abstract art. Indeed, in 1936 they became two of the co-founders of the group known as American Abstract Artists, founded to promote abstraction in the face of the dominance of Regionalism and other figurative styles in the New York art world.5

A look at the two artists’ works gives a sense of which European modernisms they favored. Morris was heavily influenced by Fernand Léger, with whom he briefly studied in 1929-30.6 From Léger Morris gained an appreciation for the brightly colored, hard-edged Synthetic Cubism the French master had codified during the 1920s. Bolotowsky, meanwhile, was heavily influenced by Piet Mondrian, a fellow recent émigré from Europe to the United States.7 For both men, abstraction was sharp, intellectual, and heavily reliant on the examples posed by the ongoing European tradition. By contrast, works like those by de Kooning are freer, looser, speaking more to the painter’s individual personality. It was this latter sort of work that would come to dominate the story of American abstraction. Though Morris, Bolotowsky, and the other artists of the AAA had tireless advocated for non-objective art, they would soon be eclipsed by wilder, younger men.8 One of the major forces in that process was the legendary art critic Clement Greenberg, whom Morris had preceded as the art critic at the influential Partisan Review. Greenberg argued that the European-derived abstraction of artists like Morris and Boltowsky was moribund, and that the new school—represented by de Kooning, Jackson Pollock, and Arshille Gorky—was reviving the Cubist tradition through the re-introduction of painterliness and emotional content.9 The rest of the art world—including, it turns out, the Museum of Modern Art—agreed. For her part, in reflecting on this realization, Elizabeth Murray remarked, “Most of all, you just see—you’re a speck. It’s interesting and humbling.”10

1 Elizabeth Murray quoted in Robert Storr and Elizabeth Murray, Elizabeth Murray (New York: Museum of Modern Art : Distributed in the United States and Canada by D.A.P./Distributed Art Publishers, 2005), 18.

2 Avis Berman, Hollis Taggart Galleries, and Fla.) Naples Museum of Art (Naples, Order and Intuition: American Abstraction from the Patty & Jay Baker Naples Museum of Art, 1913-1954 : 18 September to 25 October 2008 (New York, NY: Hollis Taggart Galleries, 2008); Debra Bricker Balken et al., eds., The Park Avenue Cubists: Gallatin, Morris, Frelinghuysen, and Shaw (New York : Aldershot, England: Grey Art Gallery, New York University ; Ashgate, 2002); Berman, Hollis Taggart Galleries, and Naples Museum of Art (Naples, Order and Intuition.

3 Berman, Hollis Taggart Galleries, and Naples Museum of Art (Naples, Order and Intuition, 11.

4 Balken et al., The Park Avenue Cubists, 8.

5 Berman, Hollis Taggart Galleries, and Naples Museum of Art (Naples, Order and Intuition, 36.

6 Balken et al., The Park Avenue Cubists, 47.

7 Berman, Hollis Taggart Galleries, and Naples Museum of Art (Naples, Order and Intuition, 110.

8 Berman, Hollis Taggart Galleries, and Naples Museum of Art (Naples, 35.

9 Balken et al., The Park Avenue Cubists, 23–25.

10Murray quoted in Storr and Murray, Elizabeth Murray, 18.