By: Fiona Harper, Professor of Marine Biology & Terri Gotschall, Associate Professor and AI Librarian

Disciplinary Why Meets Methodological How:

Professor of Marine Biology Fiona Harper brought the disciplinary why: What makes species research meaningful and how does primary literature advance biology? AI Librarian Terri Gotschall supplied the methodological how: Where do we look, how do we vet, and how do we trace a claim to its source? Together, they modeled that inquiry is a team sport: the professor set the standards of evidence; the librarian equipped students with strategies to meet them.

Fiona’s story:

As an undergraduate studying marine biology in the last century (seriously), my Invertebrate Zoology professor gave us each the scientific name of an animal that we were responsible for researching. Mine was Hippopodius hippopus (and yes, I do remember that name to this day. It’s a deep-sea weirdo called a siphonophore.)

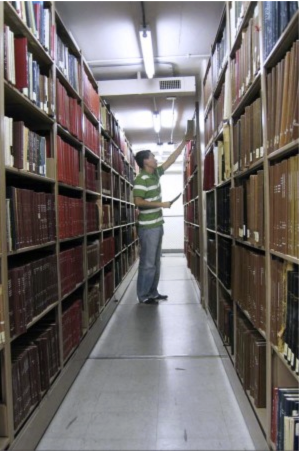

Quite honestly, it took me weeks just to figure out what my species WAS, never mind details about its biology and ecology. My first step was to actually go to the library—that physical building in the center of campus. This was in the days when Web of Science existed on CDs, so my next step was to check out a stack and then sit at a computer for several hours, looking up different keywords about my species. Next, with the complete reference in hand, I headed to the stacks of actual physical journals, organized by volume, and spent several more hours (even days), looking up the primary literature. By the end of this process, I knew about my species, but I also knew a lot about the process of research, what we now call information literacy. Though it challenged me a lot (perhaps because it challenged me?), this assignment was one of my favorite learning experiences.

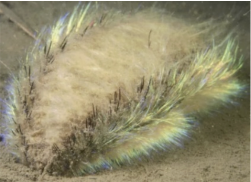

In the intervening decades, the internet has evolved into the font of information that enables my students to spend less than 15 seconds on the same task. While I delight in their happy realization that Aphrodite aculeata is a species of worm with so many spiky bristles its common name is “sea mouse”, it almost feels like they’re cheating (or being cheated?).

There are two ways I can react to how my assignment works now vs then: I can keep assigning it, knowing it is not as valuable an experience. Or I can integrate newer research tools, including how to ask better questions.

In August 2025, I arrived at the AI Course Redesign Institute (CRI) intent on making my favorite assignment “AI-proof.” I had a lot to learn. Facilitators asked us to feed our assignment to an AI and see what it produced in five minutes. The result was clarifying. AI could do enough to warrant changes but probing the tools exposed their limits: people-pleasing, hallucinations, and spotty access to paywalled scholarship.

My assignment requires at least six primary research articles on a species, published since 2010. AI couldn’t reliably meet that bar. It surfaced Wikipedia, off-topic or older papers, and sometimes citations that didn’t exist. A student not reading critically might miss those issues. That shifted my core question from “How do I block AI?” to “How do I ensure students verify what AI (and the web) provide?” The redesign now aims beyond learning about an animal; it teaches students to interrogate how they access, evaluate, and use information.

Terri’s Story:

As an undergrad, Fiona fell in love with research. Armed only with a species’ Latin name, she went to a physical building, searched through Web of Science CDs, tracked down journals in the stacks, and stitched together knowledge from primary papers. Today students don’t need to go to a physical building, and most journal articles will not be found in the stacks. They will be found 24/7 on any device with an internet connection, including the phone in their pocket. The way we seek information has changed, and it is changing again with AI. Fiona was using keyword searching while our students will be using natural language searching. Students have an abundance of easily accessible information that needs to be verified. By contrast, undergrad Fiona knew once she got to the article that it was the authoritative source.

Rather than continue to assign the assignment unchanged (and police tools), Fiona invited me, our Rollins AI Librarian, to help redesign the assignment with an information-literacy lens that takes the student through the research process, from “where would you start to look for information?” to “how do you know?”

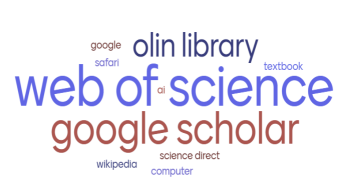

When students got their species, most did exactly what you’d expect: they Googled it and found a picture—orientation before investigation. I opened class with a poll: “Where do you want to start to find information?” They named ten paths—Web of Science (9), Google Scholar (5), Olin (3), AI (1), plus Google, Safari, ScienceDirect, textbook, Wikipedia. Access to information wasn’t the issue; sifting and evaluating were.

Fiona set two criteria: primary research and peer review. Those criteria don’t forbid the use of AI but require students to evaluate their information sources. Whether a lead came from Web of Science, the library’s catalog, or Copilot, students had to trace the claim to the original article and verify the journal’s review process. One student started in Copilot; it provided a reference to an article. The student then located the journal’s website, checked the peer-review policy, and confirmed the article’s status—an excellent use of time and judgment. My role? Make “how do you know?” the habit that outlasts any tool.

Would you like to invite Terri into one of your classes to help teach information literacy (with or without AI)? Please email tgotschall@rollins.edu

Would you like to join the Summer 2026 AI Course Redesign Institute? More info, including specific dates, forthcoming, but you can email Lucy Littler now to express your interest, crlittler@rollins.edu

Image sources:

The Joy of Stacks

https://www.thoughtco.com/sea-mouse-profile-2291398