Written by Ryleigh Burke ’23

Edits and Images by Rachel Walton and Liam Taylor King

In honor of Pride Month, this blog post is published in partnership with the LGBTQ Museum of Central Florida. The mission of the LGBTQ History Museum of Central Florida, Inc. is to collect, preserve and exhibit the history of the Gay, Lesbian, Bisexual, and Transgender community members in Central Florida. Rollins College Archives is proud to partner with this organization to share the underdocumented but still critical history of the AIDS Crisis as it was experienced by our own Central Florida community in the 1980s.

Find the Museum’s virtual timelines, exhibits, and histories at http://www.floridalgbtqmuseum.org/. Below is the LGBTQ History Museum logo and a picture of museum supporters and board members at the 2022 Orlando Pride Parade.

The National and Local Aids Crisis

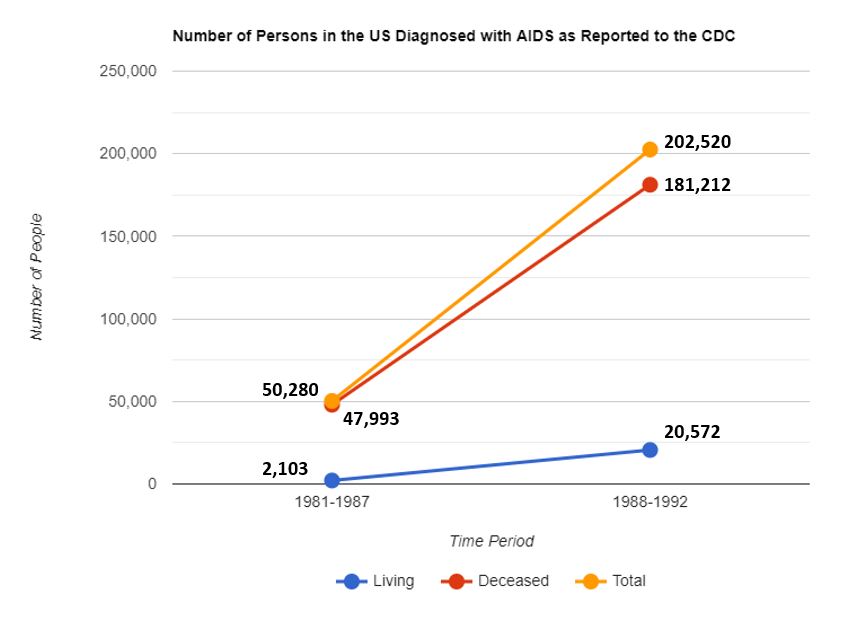

In 1980 and 1981, doctors in New York, Los Angeles, and San Francisco noticed a new form of illness that affected and killed young healthy men. A cause could not be found by medical professionals, but it was clear that the men who died from the illness suffered from the same disease. It was thus named as Human Immunodeficiency Virus (HIV), which if left untreated could develop into Acquired Immune Disease Syndrome (AIDS). No cure for AIDS and HIV could be found, and the disease spread rapidly. By 1986 there were more than 38,000 cases of AIDS reported from 85 different countries around the globe.1 A nearly exponential infection trajectory continued in the United States throughout the 1980s, eventually peaking in the 1990s.2 In fact, by 1993 AIDS had become the leading cause of death among persons between twenty-five and forty-four years of age in the United States, accounting for approximately two percent of all deaths in the country.3

Fig. 1., This data was presented in the following publication from the Center for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC): “HIV and AIDS — United States, 1981– 2000,” Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report 50 (21): 430-434, June 1, 2001. https://www.cdc.gov/mmwr/preview/mmwrhtml/mm5021a2.htm

Like most large communities in the United States, Central Florida was deeply impacted and challenged by the AIDS crisis. Between the late 1980s and early 1990s, the dramatic increase in the rate of infection and the resulting death toll was truly staggering. While in 1983 there were 236 confirmed AIDS cases in the City of Orlando, within a decade (by the Winter of 1993) there were 2,291 reported AIDS-related deaths in Central Florida and thousands of other people affected in terms of HIV and AIDS diagnoses. Due to this dramatic climb in AIDS related deaths, the city was declared a disaster zone, resulting in Orlando receiving three million dollars in federal funding for AIDS treatment, research, and counseling.4

Importantly, an AIDS diagnosis caused both mental and physical suffering for patient; the mental suffering stemmed from the depression and anxiety of having AIDS, and the physical suffering came from the bodily pain and eventual death that followed the AIDS diagnosis. Beyond these was the the terrible, isolating social stigma wrought by an AIDS diagnosis. AIDS was initially associated with marginalized groups, especially gay men, which caused a national backlash against the LGBTQ community. It’s clear that Central Florida citizens responded to the AIDS crisis by trying to understand the disease so they could better support those infected. However, the LGBTQ community was deeply hurt by the experience and those who still remember this moment can speak to the loss and trauma.

The Suffering Caused by HIV and AIDS

HIV and AIDS infected people in different ways. For example, people affected by drug addictions became infected with HIV and AIDS through sharing needles, those who needed blood transfusions, and also a mother could transmit the disease to her infant. Mostly, HIV and AIDS infected gay men through sex. By 1985, Orange County Florida reported ten cases in January in which nine people died of AIDS. The medical director of the Orange County Health Department, Dr. Betty Vaugh, reported that although Orange County experienced death through AIDS, it “certainly [did] not have the problem that larger cities such as Miami [had].”5 The number of cases was reasonable with the size of Orange County. Still, the fear in the community caused people to reject and cast out gay men in an already homophobic society.

By 1989, Florida ranked number three in the country for AIDS cases with an estimate of 8,000 cases.6 Getting a positive HIV/AIDS test result was like a death sentence in the 1980s. Many men committed suicide to prevent themselves from dying.7 However, health professionals such as Bobby Davis, director of the testing site in the Gainesville Alachua County Health Department, urged young men not to not take matters into their own hands after a positive test.8 In fact, some men who did receive a positive AIDS test did not experience symptoms or had them in a delayed timeframe. By 1987, sources say that a positive test did not mean the patient would die immediately from the disease.9

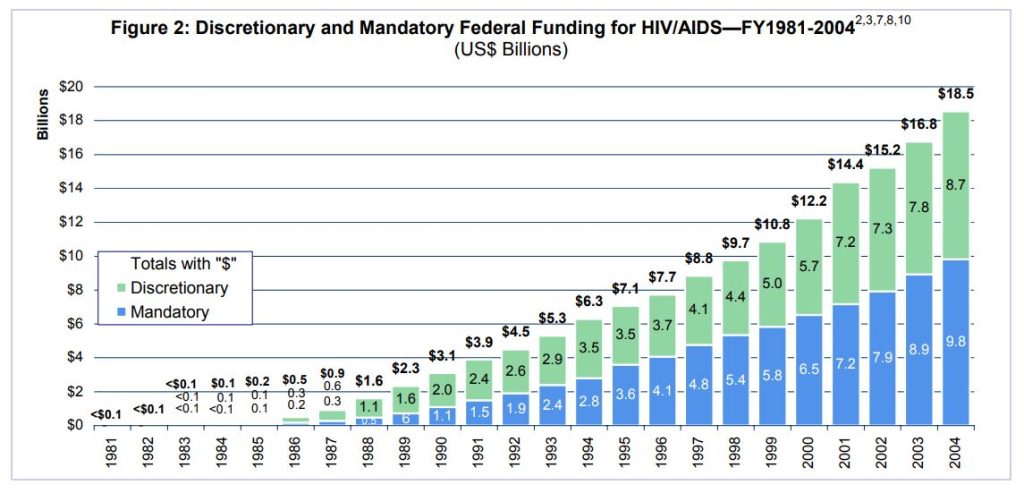

Fig. 2., This data was presented in the following publication from the Henry J. Kaiser Family Foundation website: Jennifer Kates and Todd Summers, Trends in the U.S. Government Funding for HIV/AIDS: Fiscal Years 1981-2004, (The Henry J. Kaiser Family Foundation, 2004), pages 1-2.

The National Response vs. the Central Florida Response

In 1984, President Ronald Reagan frequently dismissed and rejected homosexuality in America, going as far as defining sex as “the means by which husband and wife participate with God in the creation of a new human life.”10 The rise of the AIDS pandemic allowed some people to justify their homophobia by claiming the disease was a punishment from God. The U.S government provided limited resources for HIV and AIDS research and care from 1981 to 1983. When AIDS was first discovered in the United States in 1981, only a few hundred thousand dollars was provided by the government.11 AIDS disproportionately affected gay and bisexual men, which caused a misperception that the disease could not infect heterosexuals. However, in 1987 there was a spike in cases of AIDS and HIV, and further testing from AIDS clinics made it clear that heterosexuals could be infected through pregnancy, experimenting with their sex lives/sexuality, and needles. Government spending increased to over $300 million thereafter (see Fig. 2 above).12

Government reaction in Central Florida was similar to that of the national government. Willard Frederick was mayor of Orlando in 1981. Extant ordinances in the City of Orlando left no protections for its gay community. Like much of the rest of the United States, Orlando’s laws enabled any business owner to refuse service to someone based on their sexuality. Moreover, gay relationships were not afforded the legal status of marriage. Jim Welch, president of Gay Community Services of Central Florida and managing editor of the gay magazine New Direction, interviewed Mayor Frederick regarding the future of Orlando and its gay members. Frederick claimed that as mayor, he would “defend the rights of any citizen to live in this community free from illegal harassment because of a personal preference.”13 However, when Welch questioned Frederick about passing a city ordinance that would place a ban on discrimination based on sexual orientation, Frederick did not think it was a necessity, saying he believed there was “no history of systemic persecution of any group in this community.”14 Frederick’s response seemed ignorant of the 1977 Miami-Dade controversy involving such a non-discrimination ordinance, a case which famously launched Anita Bryant’s “Save Our Children” campaign.15

Like the national government, the local Central Florida government could not ignore the AIDS crisis as the number of infected people rose in the mid-1980s. Across the region in these years, more than nineteen clinics popped up to help handle the AIDS crisis in Brevard, Polk, Volusia, and Orange County where over twenty-thousand people were tested.16 Despite the overwhelming fear and stigma surrounding AIDS, health care providers working in these clinics provided special care for patients living with the disease. By 1986, these clinics testing for HIV and AIDS prioritized anonymity throughout the process to protect patients. The procedure for getting tested also allowed individuals to receive counseling before their appointment, sign in under a special number to protect their identity, receive positive or negative test results within a two week time period, and all were eligible for extended counseling afterwards if results turned out to be positive. The counseling component of the testing was important to health care providers because it also was an opportunity to educate those carrying the virus how to not spread AIDS.17

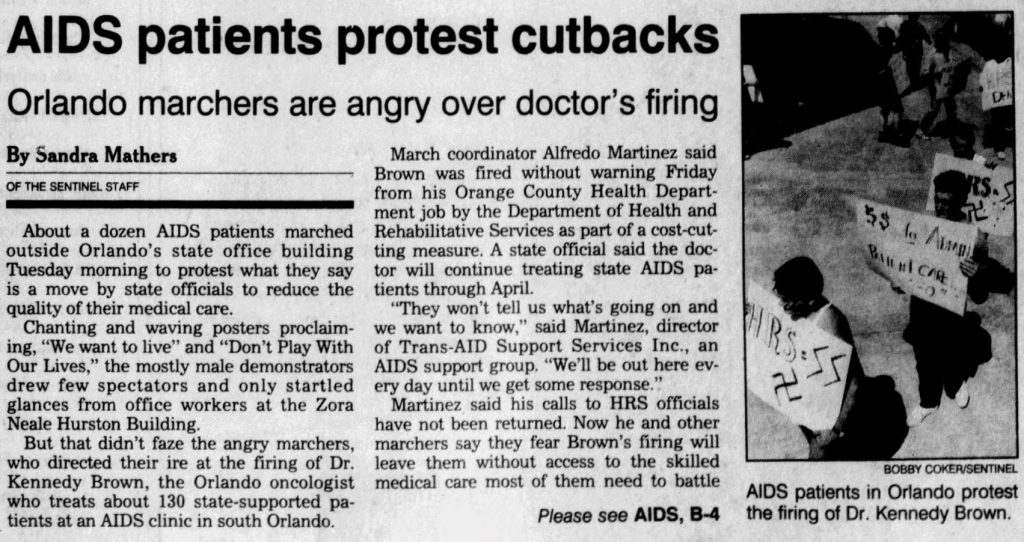

Fig. 3., AIDS patients in Orlando hosting protests for the firing of Dr. Brown, Orlando Sentinel, 1990.

Though the government provided these clinical services free of charge, activists and those closest to the AIDS crisis felt as though the local government took one step forward and two steps back when it came to the care for the LGBTQ community. By 1989, the health board deemed that if someone in the medical field could treat an AIDS patient but refused to, they would be denied a Florida medical license and would no longer be able to practice medicine.18 While this seemed a positive development, the local government seemed to take a step back a year later in 1990 when the Department of Health and Rehabilitative Services fired oncologist, Dr. Kennedy Brown, from his job at the Orange County Health Department. Dr. Brown was fired by the department rather expediently to apparently cut costs; however, this caused an uproar in Central Florida since Dr. Brown treated over one hundred and thirty patients at an AIDS clinic in Orlando and was a cherished resource for the LGBTQ community.19 Seeing the health department terminate an individual with such a vital role in the Orlando AIDS community significantly compromised the faith that the LGBT community had in the system to diagnose and treat the AIDS crisis.

More Knowledge and Community Outreach

Part of what brought the Central Florida community together during the AIDS and HIV crisis was the growing medical and public knowledge of the disease. However, in the early days, fear caused by uncertainty and misinformation drove the community apart, and a stigma was placed on homosexuality since AIDS noticeably affected homosexual men in these years.20 At first, many believed HIV and AIDS could only affect homosexuals. This was quickly proven false as positive AIDS tests in heterosexuals increased. By 1989, Florida ranked second among the states for the number of AIDS cases in heterosexuals.21 That same year, nationally 4% of AIDS cases came from heterosexual contact, however in Florida, 14% of the 7,900 AIDS cases came from straight couples.22

Fig. 4., U.S. Surgeon General, C. Everett Koop, appearing before Congress, 1989.

The more HIV and AIDS spread, the more people needed to learn about the disease. Health officials such as the AIDS program coordinator for Central Florida, William Buckley, encouraged and taught what he perceived as the safest solution to not getting HIV and AIDS: no sex, monogamous relationships, and “a poor third choice” being condoms.23 By 1986, it became clear that the dangers of AIDS needed to be taught in the school system either as part of their biology and science courses, or as apart of children’s sex education. Parents, teachers, and members of the school board in Orange County debated over when children should be taught about the diseases. U.S Surgeon General C. Everett Koop urged educators to introduce AIDS curriculum beginning in elementary schools. Orange County superintendent, James Schott, disagreed with the surgeon general and decided that middle school would be a better time to teach children about HIV and AIDS. Chairwoman of the Orange County School Board, Irish Tapley, agreed with Schott’s opinion to educate children about AIDS when they reach middle school.24

It was a controversial subject due to the backlash that could stem from people who were generally against sex education in public schools. Opponents of sex education wanted abstinence to be the only prevention taught in public schools, but the Surgeon General’s plans would involve lessons about using condoms as preventatives. Surgeon General Koop wanted to spread awareness of the disease and was openly concerned about the amount of people who “placed conservative ideology far above saving human lives.”25 Jim Dawson, coordinator of health and physical education for Seminole County schools, understood the potential backlash Orange County schools could face from opponents of sex education saying “If you get into the use of condoms…then they [those opposed to sex education] would say you’re not telling them it’s wrong to do in the first place.”26 Though there was a mixed response on how AIDS was taught in public schools, members of the school board and members of the Central Florida community recognized the importance of educating youth about HIV and AIDS.

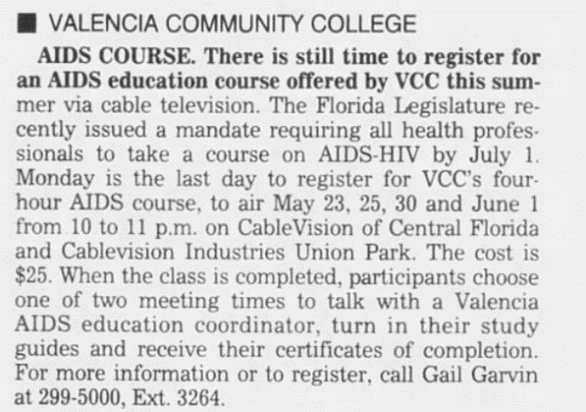

Fig. 5., Ad for a four-hour AIDS course at Valencia Community College, Orlando Sentinel, May 1989.

The discussion of AIDS in the classroom went beyond elementary and middle schoolers. By 1989, local schools in Central Florida posted ads in the newspapers regarding different class courses that taught medical students about AIDS. Classes, such as the ones provided by Valencia Community College, were offered due to new requirements placed on those working in the medical community. The Florida Legislator made it mandatory for all medical professionals to study HIV and AIDS in order to properly treat those with the disease.27 The mandate followed the 1988 Florida Omnibus AIDS Act. Through this act, a person could not receive HIV testing without their consent and could not be discriminated against by medical workers if they were HIV or AIDS positive.28

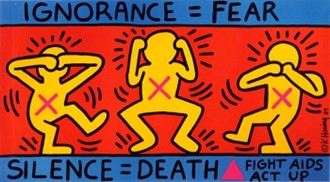

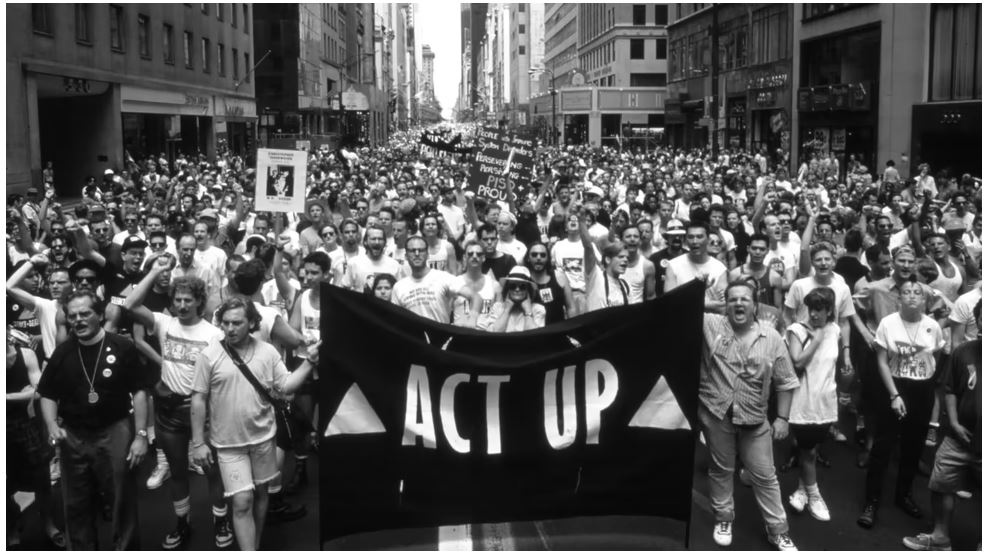

By 1986, the public became more educated on HIV and AIDS through a combination of public school sex education, professional training, media attention, and public protests. Local citizens were beginning to realize the lack of effort politicians and government officials put into fighting the AIDS crisis and resented mislabeling the crisis as “the gay plague.”29 Citizens reacted in a variety of ways. Some Americans got involved with ACT UP (an activist group that stands for the AIDS Coalition to Unleash Power). Founded in New York City and active in cities all over the U.S., the group ACT UP made headlines for protesting about and advocating for greater action surrounding AIDS patient rights. Its mission was to educate others and create a voice for the LGBTQ community. Protestors marched in the streets holding signs “No Business as Usual” and signs with a pink triangle with the words “Silence = Death” written underneath.30 The goal was to get attention to the AIDS crisis and to destigmatize homosexuality.

Fig. 6., The famous “SILENCE = DEATH” AIDS protest art from activist group ACT U (Art by Keith Haring).

Fig. 7., ACT UP group at the New York City Pride March in 1989 (Photograph by T. L. Litt).

Members in the Orlando community also participated in World AIDS Day, when people came together for the fight against AIDS, offered support those with the disease, and mourned those lost to it. Members of the gay community wrote poems describing their relationship to HIV and AIDS, and others contributed by donating to charities for AIDS. Church congregations and local colleges such as Rollins took part in world AIDS day by tolling their bell towers 15 times in 1995.31 The theme in that year was “Shared Rights, Shared Responsibility,” signifying the right for a member of the gay community to receive medical treatment and the responsibility of the community to protect themselves and others from potential infection.

Parliament House, a gay resort on Orange Blossom Trail, contributed support to the LGBTQ community during the AIDS pandemic in Orange County. Bought by Michael Hodge and Bill Miller in 1975, the Parliament House became a cherished gay venue with a bar and nightclub, and it was also a safe haven for members of the LGBTQ community who felt they could be themselves without hiding their chosen lifestyle or identity. According to a performer and customer at the Parliament House, Michael Wanzie, co-owner Miller did not want the resort to be published in papers or magazines as he felt it put them at risk for potential homophobia from the greater public.32

When AIDS started to show up in the Central Florida community, Parliament House felt its effect. Former manager, Bill Lape, recalls losing many customers he considered friends, and estimated that he was going to “at least one funeral a week” due to the many AIDS-related deaths experienced by the Orlando community. Vicki Bebout, a bartender at the resort, claimed she had to quit counting how many Parliament House attendees died from AIDS when she got to 130 deaths.33 Owners Miller and Hodge wanted to help those in the community suffering from the disease. With the help of customers, Miller and Hodge raised money, and created AID Orlando. Money was raised in order to help pay for people’s medical bills, groceries, and even rent and electric bills since those with the disease were often too sick to work.34 Various plays and drag shows were held at the fundraisers to help raise money, and if there was not enough money raised, Miller and Hodge would go into their personal funds to help those in need. Parliament House was a place that made members of the LGBTQ community feel safe, and it helped spread awareness of the impact of the AIDS pandemic.

Fig. 8., Brochure of the Parliament House Motor Inn, late 1970s.

Fig. 9., Frontal view of Parliament House the year of its grand opening, 1975.

Fig. 10., Parliament House owners, Bill Miller and Michael Hodge, 1975.

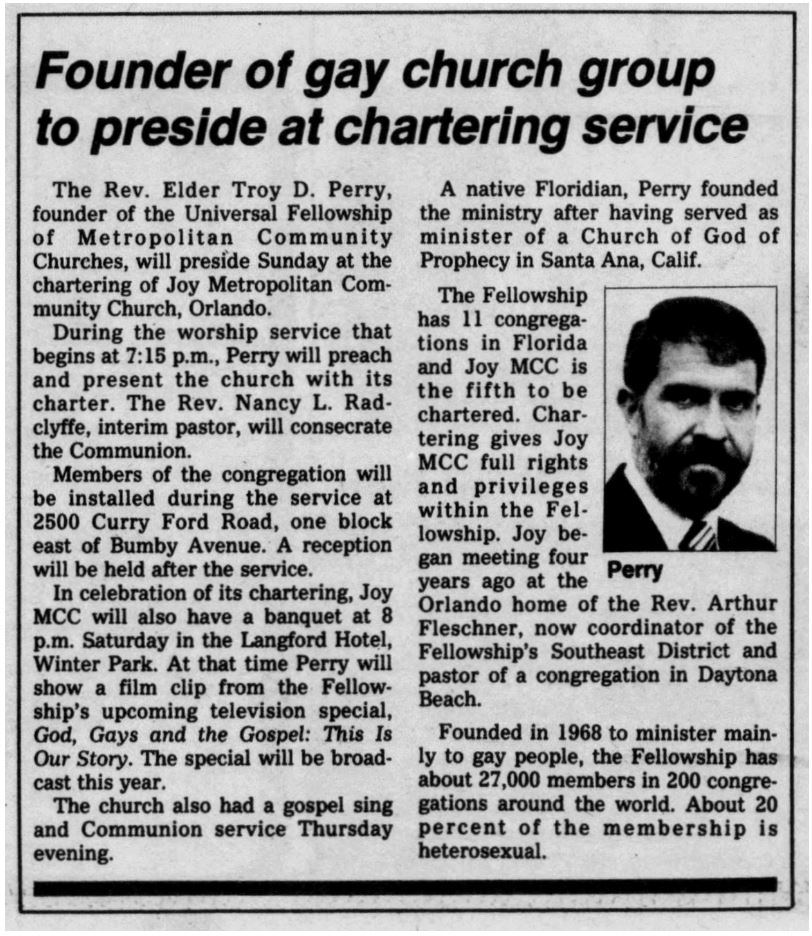

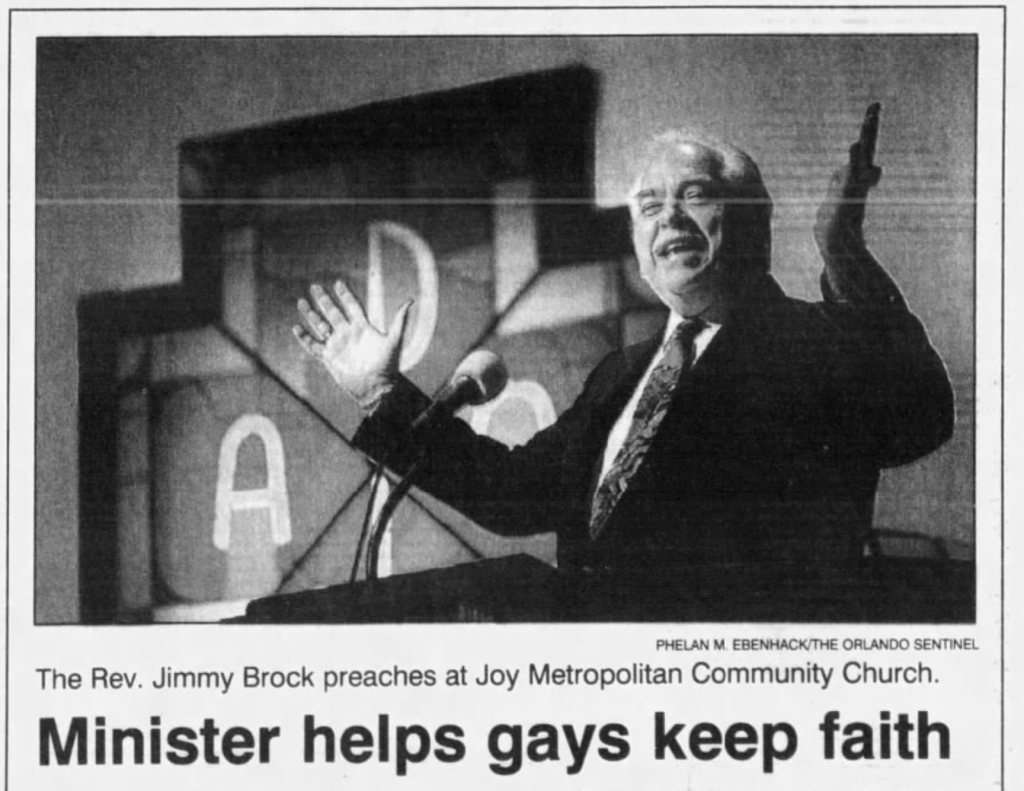

Joy Metropolitan Community Church (Joy MCC) also became a safe space for queer men and women. The national church was founded in 1968 by Reverend Elder Troy D. Perry, who was also founder of the Universal Fellowship of Metropolitan Community. The Joy MCC in Orlando started meeting together as early as 1979. It 1983 it became the fifth MCC to be chartered out of eleven total congregations. This means that Joy MCC had full Fellowship privileges such as having a large space to worship and receiving funds. The church primarily served as a place of worship to the LGBTQ community, and 80% of its members were homosexual in 1983.35 Reverend Jimmy Brock, a gay minister at Joy, claimed that members of the LGBTQ felt like outcasts in other churches which also made them feel like they had no connection to God. Joy did the opposite, and even celebrated holy unions for gay couples when gay marriage was outlawed.36 By 1986, Joy MCC took part in a nation-wide vigil for more than 50 hours in honor of AIDS victims. The vigil allowed people to pray for those suffering from HIV and AIDS, as well as spread attention to the public regarding the AIDS pandemic.37 Members of the church suffered from the disease, and by 1995 one third (100 men) of the congregation died due to AIDS. 38 To further support victims of the AIDS pandemic, Joy MCC raised money and started an AIDS ministry where people could receive counselling through the church.

Fig. 11., Article about Rev. Elder Troy D. Perry, Founder of Joy MCC, Orlando Sentinel, March 1983.

Fig. 12., Article headline about Rev. Jimmy Brock, leader of Orlando’s Joy MCC, Orlando Sentinel, April 1995.

Those Affected by the AIDS Crisis

The rest of this blog post is dedicated to individuals who contributed to AIDS awareness and advocacy in Central Florida. Some of these individuals also passed away as the result of AIDS. This tribute offers a small memorial to their extraordinary efforts and their meaningful contributions to the LGBTQ and greater Orlando community.

Fig. 13., Michael Leroy Thompson, AIDS relief donor and AIDS victim.

Michael Leroy Thompson died on January 20, 1994, due to complications from AIDS at the age of 36. He was an important pillar in the Central Florida community as he raised thousands of dollars for AIDS donations to benefit those affected and their families. He raised those donations using his passion for entertainment and produced a “Voice…A Time to Listen.”39 He combined his passion of activism and performance to help those suffering from the AIDS pandemic.

Fig. 14., Ron Kimber, AIDS victim.

Ron Kimber died of lymphoma caused by HIV-AIDS at age 23 on February 13, 1987. Kimber lived in Winter Park and was said to be happy, easy going, and extraverted. He found love with his partner Michael Wanzie, who supported Kimber after his father disowned him for coming out. Kimber did not speak to his family until he laid in his deathbed, but in his final moments he extended forgiveness to them.40

Fig. 15., Charlene White, activist and caregiver who supported the fight against AIDS.

Charlene White died in July of 2002 and was an activist and founder of the Serenity House Pediatric AIDS Foundation. She and her husband became the first foster parents for children with HIV and AIDS in Central Florida. Charlene and her husband adopted six children, and most of her children were born through women who tested positive for HIV. Through her work, she created safe spaces for children born from HIV and AIDS-positive mothers, as well as helped to destigmatize the fears people had surrounding the spread of HIV and AIDS.41

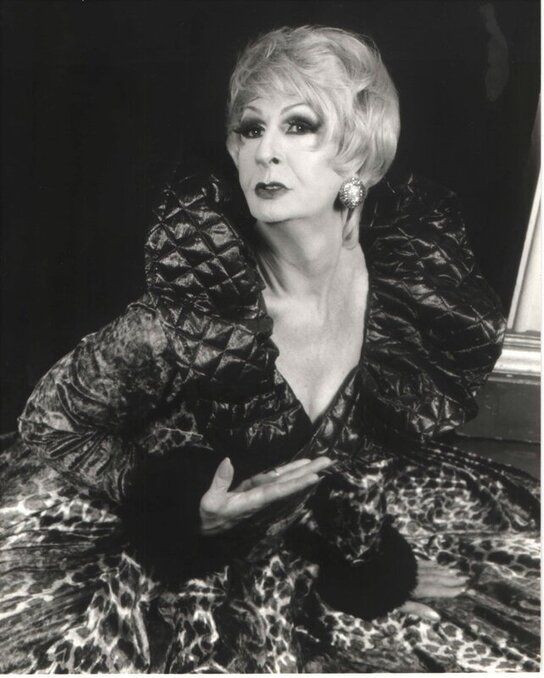

Fig. 16., Paul Michael Wegman, AKA: Miss P, beloved performer, educator, and activist who fundraised for AIDS patients and fought a personal battle with AIDS.

Paul Michael Wegman was a well-known performer and activist in Central Florida. He worked at the Parliament House as a drag queen — known as Miss P — throughout the 1980s and 1990s and was highly requested by customers. Through his work in drag, Wegman was able to raise money for multiple AIDS charities such as AID Orlando. He also worked for Valencia Community College as a professor before he died in August 2004 due to complications from AIDS.42

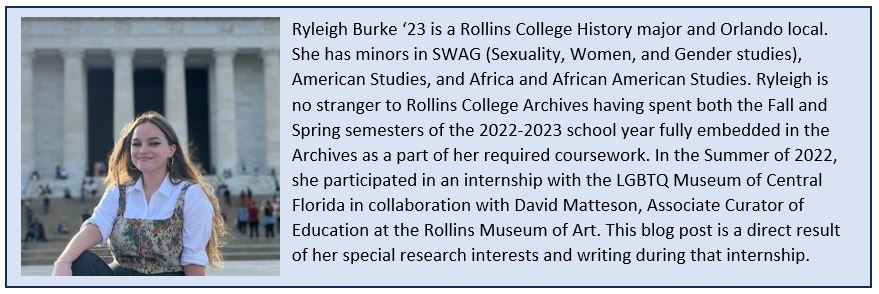

About the Author: Ryleigh Burke

Ryleigh can be contacted at mburke@rollins.edu or via her LinkedIn.

1. University of California San Francisco Timeline, “40 Years of Aids,” by Lisa Cisneros. https://www.ucsf.edu/news/2021/06/420686/40-years-aids-timeline-epidemic

2. John D’Emilio, Intimate Matters: A History of Sexuality in America, (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2013), 354.

3. Weeks, Andrew. A Legacy of Community and Mourning: AIDS & HIV in Central Florida, 1983-1993 (2020). Pages 40-41. https://stars.library.ucf.edu/etd2020/149/

4. Weeks, Andrew. A Legacy of Community and Mourning, 2020.

5. Jeff Kunerth, “Myths aside, it’s everybody’s problem,” Orlando Sentinel, January 29, 1985.

6. Harold Lipvendahl, “AIDS message falls short,” Orlando Sentinel, November 27, 1989.

7. Pelton M at al. “Rates and risk factors for suicidal ideation, suicide attempts and suicide deaths in persons with HIV: a systematic review and meta-analysis.” General Psychiatry, 34:e100247, April 2021. http://www.doi.org/10.1136/gpsych-2020-100247

8. Diane Hubbard Burns, “’AIDS test’ is agonizing choice for all,” Orlando Sentinel, July 19, 1987.

9. Diane Hubbard Burns, “’AIDS test’ is agonizing choice for all.”

10. John D’Emilio, Intimate Matters, page 345.

11. Jennifer Kates and Todd Summers. Trends in the U.S. Government Funding for HIV/AIDS: Fiscal Years 1981-2004. The Henry J. Kaiser Family Foundation, 2004, pages 1-2.

12. Diane Hubbard Burns, “’AIDS test’ is agonizing choice for all.”

13. Harry Straight, “No gay week disappoints Orlando group leader,” Orlando Sentinel, June 17, 1983.

14. Harry Straight, “No gay week disappoints Orlando….”

15. Gillian Frank, “The Civil Rights of Parents: Race and Conservative Politics in Anita Bryant’s Campaign against Gay Rights in 1970s Florida,” Journal of the History of Sexuality 22, no. 1 (January 2013): 126-60.

16. Diane Hubbard Burns, “’AIDS test’ is agonizing choice for all.”

17. Diane Hubbard Burns, “’AIDS test’ is agonizing choice for all.”

18. Judith Nygren, “Board decries refusing AIDS treatment,” Orlando Sentinel, June 15,1989.

19. Sandra Mathers, “AIDS patients protest cutbacks,” Orlando Sentinel, April 18, 1990.

20. Neal King, “HIV/AIDS and Education: Lessons from the 1980s and the Gay Male Community in the United States,” United Nations: https://www.un.org/en/chronicle/article/hivaids-and-education-lessons-1980s-and-gay-male-community-united-states.

21. Harold Lipvendahl, “AIDS message falls short.”

22. Michele Cohen, “Florida tops average in heterosexual AIDS,” South Florida Sun Sentinel, June 25, 1989.

23. Diane Hubbard Burns, “’AIDS test’ is agonizing choice for all.”

24. Diane Hubbard Burns, “When should schools tell about AIDS,” Orlando Sentinel, October 29, 1986.

25. Holcomb B. Noble, “C. Everette Koop, Forceful U.S. Surgeon General, Dies at 96,” The New York Times, February 25, 2013.

26. Diane Hubbard Burns, “When should schools tell about AIDS.”

27. “Education Notebook,” Orlando Sentinel, May 14, 1989.

28. Jack P. Hartog and Gary Robinson, “Florida’s Omnibus AIDS Act: A Brief Legal Guide for Health Care Professionals,” Florida Health, August 2013.

29. Ruel, Erin, and Richard T. Campbell. “Homophobia and HIV/AIDS: Attitude Change in the Face of an Epidemic.” Social Forces 84, no. 4 (2006): 2175.

30. Han Powell, “Queer Nightlife, Joyous Resistance, and the Legacy of ACT UP,” the Columbia Center for Oral History Research blog: http://oralhistory.columbia.edu/blog-posts/People/queer-nightlife-joyous-resistance-and-the-legacy-of-act-up

31. Mark I. Pinsky, “More than 150 regional bells to mark toll of AIDS in past 15 years,” Orlando Sentinel, November 27, 1995.

32. David Bain and Michael Wanzie, 40 Years of the Parliament House, directed by David Bain (July 27, 2015): https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=pV7jKjWtZuA.

33. David Bain and Michael Wanzie, 40 Years of the Parliament House.

34. David Bain and Michael Wanzie, 40 Years of the Parliament House.

35. John Gholdston, “Founder of gay church group to preside at chartering service,” Orlando Sentinel, March 11, 1983.

36. J. Russell White, “Minister helps gays keep faith,” Orlando Sentinel, April 9, 1995.

37. Jay Hamburg, “200 Hold candlelight vigil for AIDS victims,” Orlando Sentinel, September 7, 1986.

38. J. Russell White, “Minister helps gays keep faith.”

39. “Memorial: Michael Leroy Thompson,” LGBTQ History Museum of Central Florida – Digital Archive: https://floridalgbtqmuseum.omeka.net/files/show/13022.

40. “Ron Kimber,” LGBTQ History Museum of Central Florida, Digital Archive: https://floridalgbtqmuseum.omeka.net/files/show/12951.

41. “Charlene White” (Obituary), Orlando Sentinel, July 7, 2002.

42. “Miss P: An Exhibition of the Life of Paul Wegman, Central Florida’s Drag and Theatrical Icon,” LGBTQ Museum of Central Florida, Digital Exhibit: https://paulwegman-missp.weebly.com/.