From its founding in 1885, Rollins has been a coeducational institution of higher learning. Setting itself aside from other colleges in the United States which were typically male-only institutions, with the exception of few female-only schools, Rollins welcomed both genders on campus and provided academic opportunities geared towards the interests of each group. Since Rollins was coeducational from the beginning, it is important to note and analyze the different opportunities created for women at the college and how this type of curriculum is still relevant.

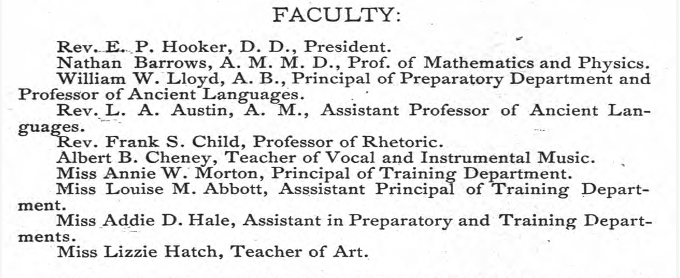

In addition to female students being on campus, women were also among the first professors to teach at Rollins in the early years. Notably, in the 1886-1887 academic year, four of the nine faculty members in the Preparatory Department listed were women, including Annie Morton, Louise Abbott, Addie Hale, and Lizzie Hatch.[1] Due to the fact that Rollins was located in what was considered rural and remote in the 1880s, the college had limited access to well-qualified professors compared to other institutions in the Northeast, where were more well-known and prestigious. However, this actually worked to the advantage of women in the academic field who were looking to gain experience in a collegiate setting, as Rollins provided them with this rare opportunity.

Eva Root, a professor of Science at Rollins (1890-1897), exemplified the college’s progressive stance on women in higher education. Root was a highly qualified candidate for her role at Rollins as she had a Master of Arts degree and was well versed in multiple languages, including Latin and French.[2] Root’s background in STEM was a rarity for women in the nineteenth century. Her experiential method of teaching did not go unnoticed, as one student remembered her for her practical application of science in the classroom, going above and beyond the typical classroom standard of recitation.[3] Root offered hands-on experiences for her students to make the class as engaging as possible, which oftentimes meant getting out of the physical classroom. Here, Root leads an astronomy class in 1890, showing her students what can be seen through the lens of the telescope.

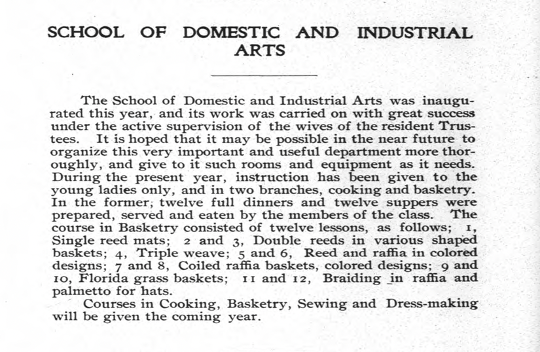

In addition to Rollins’ offering of STEM courses, Rollins provided other academic opportunities specifically for its female students. At this time in the early twentieth century, women were focused on being homemakers, wives, and mothers. The first signs of female-oriented programs are shown in the 1902 Academic Catalogue, as Rollins offered a School of Domestic and Industrial Arts. While Domestic Arts may not be seen as progressive today in that it did not help women enter the professional sphere, it instilled in these young female students the practical skills they were most likely going to need as future homemakers. This regiment of courses geared toward female students included classes such as cooking, “bakestry,” sewing, and dressmaking and were designed for “young ladies only.” These courses were supervised by the wives of the resident Trustees at Rollins.[4] In the cooking branch of the program, the students were to prepare “twelve full dinners and twelve suppers” which were then eaten by the members of the class. The purpose of this program was to prepare young women for the roles they would obtain in society, mainly in the domestic sphere.

The School of Domestic and Industrial Arts as seen in the 1902-1903 Rollins College Catalogue. https://scholarship.rollins.edu/catalogs_liberalarts/113/

Soon after the school ended their Domestic Arts department, Rollins began offering a two-year intensive Home Economics program for women to train and take classes geared towards domestic management. This program offered women the opportunity to pursue an applied degree, not typically associated with a liberal arts school. The program was particularly crucial after the United States entered World War I in 1917. As described in the 1918-1919 Rollins Academic Catalogue, “Training in Home Economics, always useful and desirable, is especially important at this time because of war conditions.” The Home Economics program had courses in Chemistry, Household Management, Marketing, Bacteriology, Dietetics, and Physiology, to name a few. This level of advanced coursework was unheard of for women’s curriculum at the time, as it incorporated scientific and mathematical elements in its workload. Furthermore, these courses differed from Rollins’ previous Domestic Arts department in their strong incorporation of STEM-based learning objectives. As women’s’ professional needs changed in society, the Rollins curriculum had to adjust, as well.

https://www.jstor.org/stable/community.38481965

During the 1940s as the United States entered World War II, many male students at Rollins were away, enlisted in the war effort. Throughout this tumultuous decade, women participation in typically male-dominated fields of study, such as Science, increased. In 1941, the Rollins Astronomy class was featured in the Winter Park Herald newspaper for their innovative class meetings outside at dark to examine the night sky. In this photo, most of the students present are females, an oddity for an Astronomy class. One of the professors here is a female too — Dr. Phyllis Hutchings. She is seen pointing out the various constellations appearing in the nighttime sky. This photo, when compared to the earlier photo of Eva Root’s class, holds many similarities. Both photos convey how Rollins remained committed to a practical education philosophy; the point of class is to apply what was learned in class, rather than just simply memorizing facts. At this same time in the 1940s, the Rollins Science Department experienced a major cut in the number of majors, due to the large portion of male students gone for the war. In the 1944 Tomokan, the yearbook also acknowledges the college’s contribution in the training of Army technicians through their Chemistry and Mathematics programs, and that they remain committed to producing more men and women able to aid in the warfront.[5]

Rollins’ involvement in the war effort contributed in more ways than one. In the 1940s, Rollins had the Civil Aeronautic Authority Program (CAAP). The purpose of this government sponsored program was to train pilots, especially in the time of the impending war looming on the United States’ horizon. Rollins’ lush campus and ideal climate made them the prime location to host the government flying program. By the end of the 1941 academic year, the college trained over one hundred pilots, and students flew over 3,000 hours without a single mishap. It was also noted that CAAP would have allowed up to ten percent of participants to be female students. [6] Overall, this program effectively equipped students with the technical training necessary to practice STEM related skills, while also contributing to their country in a desperate time of need. At the end of 1943, Florida was home to about one hundred seventy air force bases.[7]

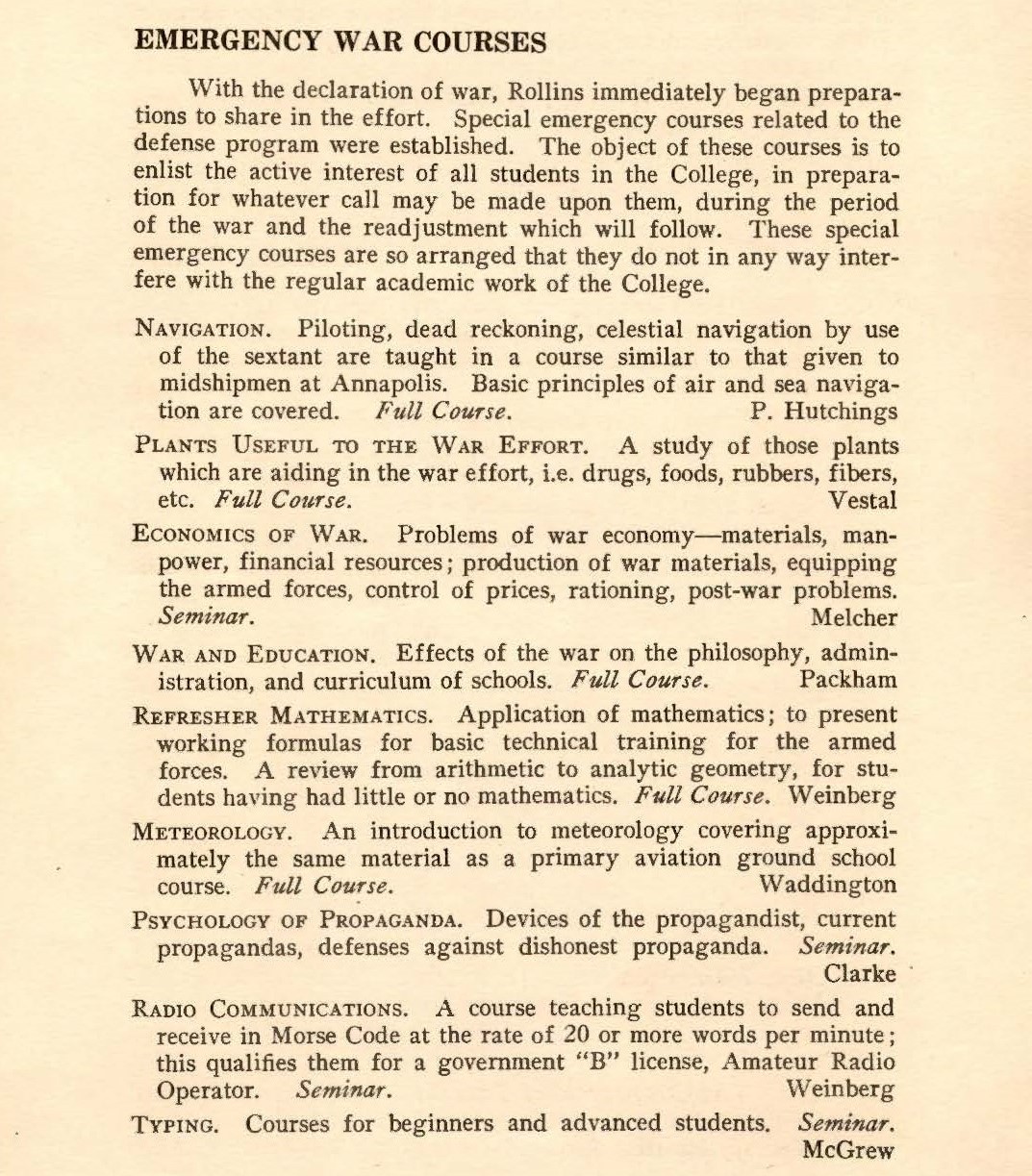

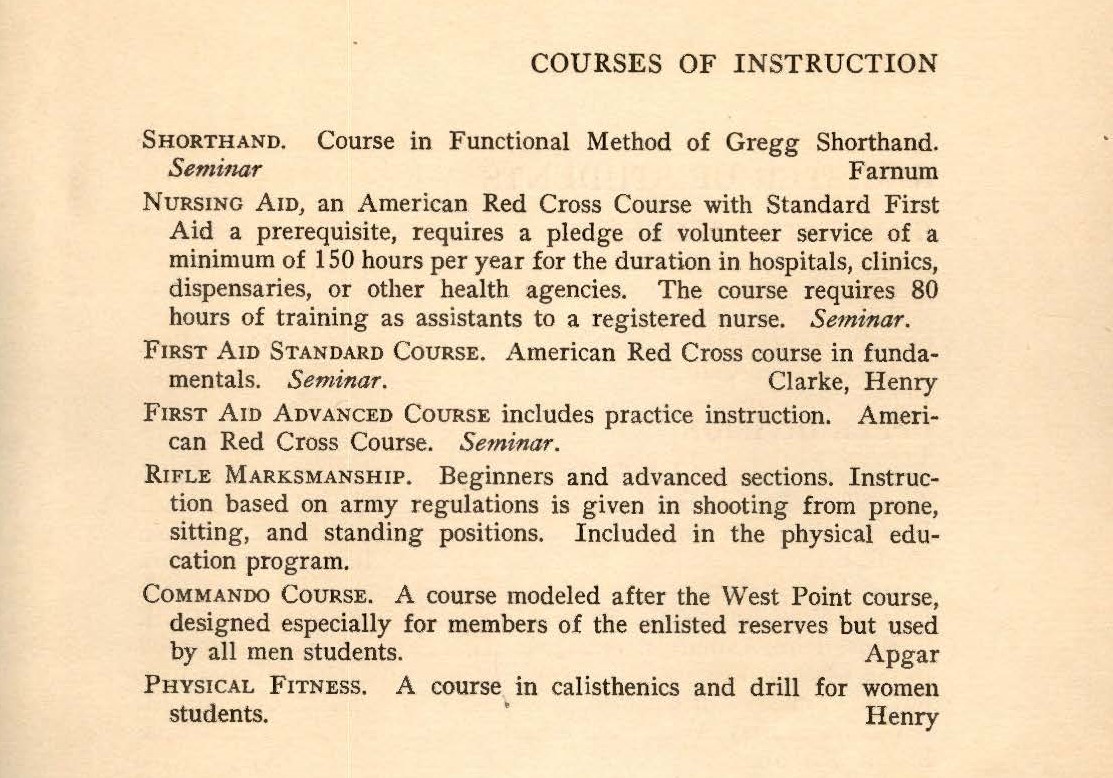

Rollins’ commitment to training students for the war was extended through a set of 16 courses added to the 1942 curriculum that were designated “Emergency War Courses.” Some of the courses in the defense program included Navigation, Economics of War, Meteorology, Radio Communications, Psychology of Propaganda, Typing, Nursing Aid, and more. Despite all of these war classes geared toward men, there was a greater ratio of female graduates in 1942 and registered students.[8]

Continuing into the 1950s, specific courses for women at Rollins focused on preparing them for household tasks and duties. In 1951, Rollins offered a one-hour seminar course titled, “Everyday Finance for Women.” According to the curriculum guide, the class was “designed to help women with their special problems of finance.”[9] While there are no specifications as to what the course entailed, it can be imagined that women were taught how to manage household budgets for their families. Like the Home Economics program from the earlier half of the twentieth century, a finance class for women served as an important outlet for teaching necessary domestic management skills for future housewives.

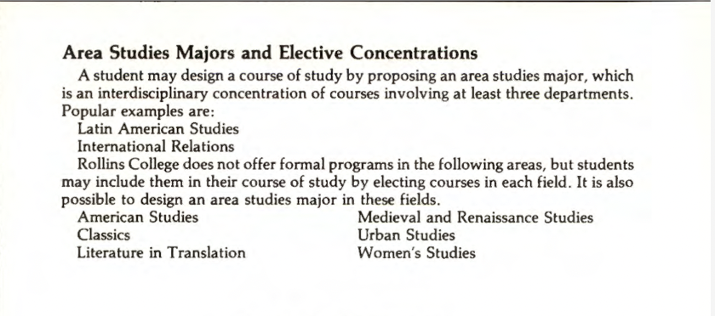

Transitioning into the 1960s and 1970s, the United States began undergoing a new stage in women’s liberation with the rise of the second wave of feminism. Coinciding with the changing culture and attitudes towards gender equality, Rollins included a women’s studies program in the curriculum for their Continuing Education School as soon as 1974.[10] Rollins later added Women’s Studies as a program of study to the general curriculum in 1981. While the College did not offer formal courses on the topic, some of the electives that counted towards that track included The Family, Sociology of Women, Sex and Gender Roles, and Intimacy and the Future of Marriage.[11] This inclusion of the Women’s Studies program gave new opportunities for women to engage in courses that address their history and examine how race, gender, ability, and class shape the experiences of individuals and groups.[12] Today, the program has broadened into the study of Sexuality, Women, and Gender (SWAG). SWAG has now evolved into a minor, rooted in recognizing social injustices and intersectionality, that educates students on how to address these societal issues.

The first time Women’s Studies was formally listed as a major in the Rollins College Catalogue of 1981-1982. https://scholarship.rollins.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1048&context=catalogs_liberalarts

Today Rollins also offers the chance for female students to explore opportunities in the world of business, as well as other majors. Through the “Women in Finance” program, female students are able to explore special summer internships, participate in independent studies, receive advanced Excel training through the Office of Business Advising, and benefit from mentoring with faculty in the Crummer Graduate School of Business. The Women in Finance program aims to prepare women to fulfill jobs in finance post-graduation, as women currently only hold 18 percent of these jobs in the workforce and are therefore still very underrepresented.[13]

Rollins continues to strive for gender equality both inside and outside of the classroom. As the social climate of the United States is ever changing, the Rollins curriculum will fluctuate and adapt accordingly. The College’s humble offerings in sewing and baking at the turn of the century have dramatically evolved, with women now having a special part in the college’s prestigious and popular business program. As the role of women in higher education is an relatively understudied concept in our nation’s history, it is imperative to continue to advocate for and protect and values of gender equality and the opportunities for women teachers and learners on the Rollins campus.

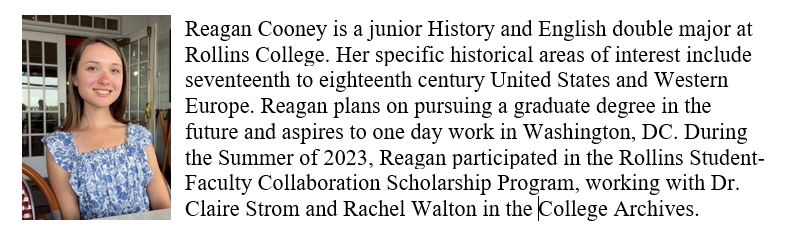

About the Author:

[1] Catalogue, 1886-1887, Rollins College Course Catalogues, Rollins College Scholarship Online, https://scholarship.rollins.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1161&context=catalogs_liberalarts.

[2] Eva Josephine Root biography, https://lib.rollins.edu/olin/oldsite/archives/golden/Root.htm

[3] Jack C. Lane, “Liberal Arts on the Florida Frontier: The Founding of Rollins College, 1885-1890.” The Florida Historical Quarterly 59, no. 2 (1980): 144–64. http://www.jstor.org/stable/30146100.

[4] Catalogue, 1902-1903.

[5] Tomokan yearbook (1944): 96. https://scholarship.rollins.edu/tomokan/73/.

[6] “Rollins Flying Program 1941,” https://www.jstor.org/stable/community.38481701

[7] Claire Strom, “Controlling Veneral Disease in Orlando during World War II.” The Florida Historical Quarterly 91, no. 1 (2012): 86–117.

[8] Catalogue, 1942-1943.

[9] Catalogue, 1951-1953.

[10] “Pamphlet for Division of Continuing Education,” Rollins College Archives and special Collections, Olin Library, Rollins College, Winter Park, FL.

[11] Catalogue, 1981-1982.

[12] “Sexuality, Women’s, and Gender Studies,” Rollins College, accessed April 21, 2023, https://www.rollins.edu/sexuality-womens-gender-studies/.

[13] “Women in Finance Program,” Rollins College, accessed April 21, 2023, https://www.rollins.edu/academics/women-in-finance/.