Written by Wenxian Zhang

Throughout human history, civic activism has been a major force that drives social changes in our world. Contrary to the stereotype of the elitist ivory tower, Rollins as a liberal arts institution has a rich history of social activism. Over the years, besides vigorous pursuit of knowledge and intellectual engagement, Rollins faculty, staff, students, and alumni have been contributing members of society who seek to make a difference in local and global communities.

Taking a Stand to Defend the Freedom of Inquiry

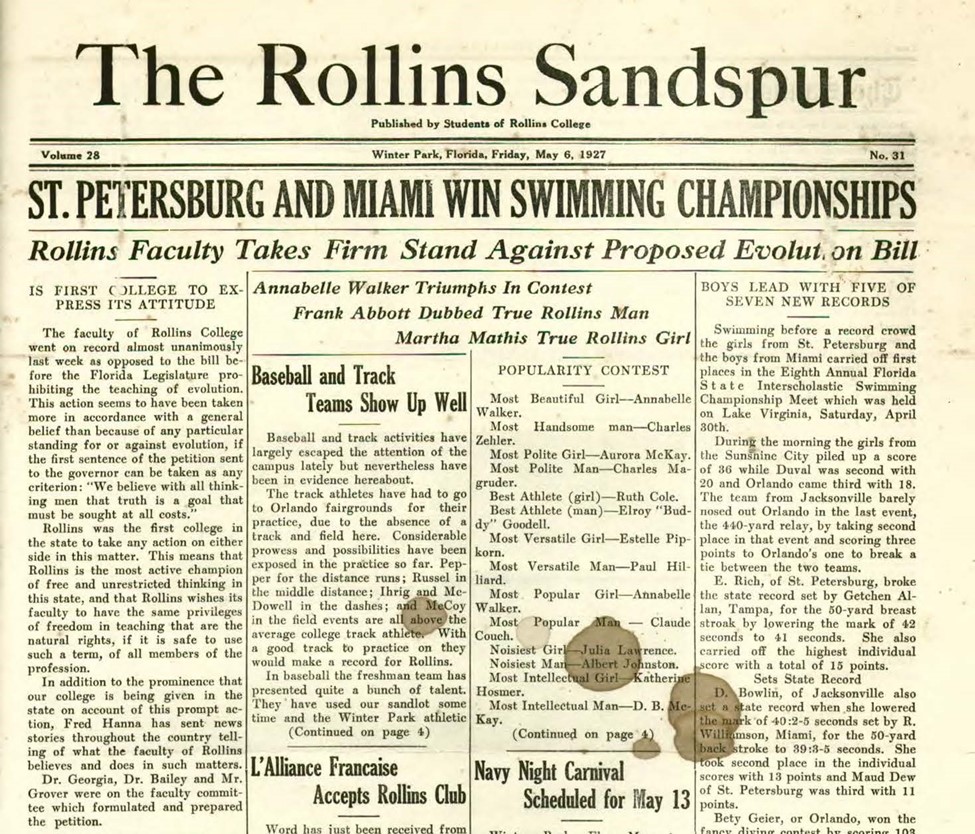

In the early twentieth century, one of the notable cases of social activism at Rollins was the official protest by faculty against the proposed anti-evolution legislation in Florida. Known as “a year of monkey war,” the 1927 state legislative session saw an ardent group of conservative legislators push for the passage of new laws to eliminate the teaching of evolution in the classroom and to establish close surveillance over textbook selection at educational institutions.[1] As the Florida House began its deliberation on the anti-evolution bill, Rollins faculty members took a strong stand to defend a fundamental principle — freedom of inquiry and teaching, or academic freedom. They addressed an open letter to Governor John W. Martin and members of the state legislature declaring:

“We believe with all thinking men that truth is a goal that must be sought at all costs. We believe that the purpose of both religion and science is to seek the truth… We believe that any school or educational institution that is not seeking the truth is disloyal to its ideals and failing in its duty to its students… We believe that freedom of teaching is as essential to human welfare as freedom of conscience, freedom of speech and freedom of assembly, which are guaranteed by the Constitution of the United Sates. We the undersigned, therefore, respectfully petition the legislature of the State of Florida not to enact any law that limit the seeking or the teaching of truth in science or in any other realm of thought. You shall know the truth and the truth shall make your free.”[2]

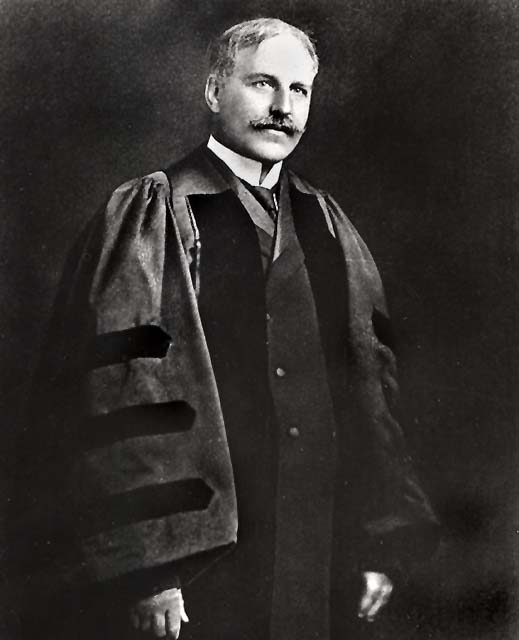

According to the New York Times, the Rollins petition constituted “the first official protest from any school, college or university in Florida against the Anti-Evolution bill now before the legislature.”[3] Inspired by faculty action, President Hamilton Holt also issued a public statement wherein he revealed that he had refused a large endowment when the intended donor demanded that evolution not be made a part of the college curriculum.[4] He explained, “A college that limits its own freedom is a propaganda institution by choice. A college that is required to limit its freedom is a propaganda institution by compulsion… I consider it the duty of those entrusted with the education of youth, in a crisis of this kind, is to not to take an easy and safe course of silence but to make public their convictions. I deem it an honor to be associated with a faculty whose members take these views.”[5] In the end, despite the approval of the Florida House by a vote of 67 to 24, a strong opposition from a coalition of scientists, journalists, and educators resulted in the drafted anti-evolution legislation being soundly defeated in the Education Committee of the State Senate.[6]

Combating Racial Segregation in the Jim Crow South

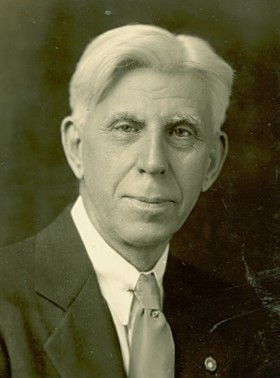

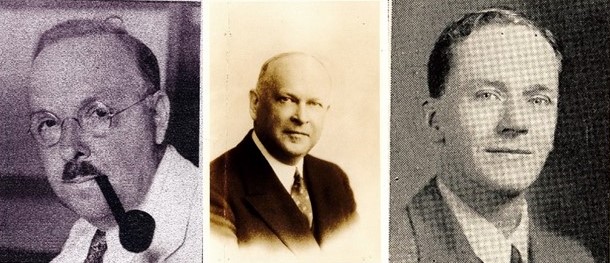

In the late nineteenth century, because of the “Separate but Equal” doctrine, the Florida legislature had passed laws to ensure racial segregation in the state’s education systems. Accordingly, Rollins was founded and operated as a segregated, white-only school. However, throughout the era of segregation, certain brave members of Rollins academic community fought against the racial discriminations in the Jim Crow South. Being the only college in the greater Orlando area since the late nineteenth century, Rollins provided social, political, and financial supports to the education of Black youth in Central Florida in various ways. Founded in 1899, the Robert Hungerford Normal and Industrial School of Eatonville, Florida was a vocational training program for African Americans, only a few miles from Rollins’ campus. Rollins instructors and Presidents were active advocates for the school’s funding and success. Nathalie Lord, an early Rollins staff member, served on the Hungerford Board of Trustees for many years. Presidents William Blackman and George Morgan Ward, and Treasurer William O’Neal also lent their strong endorsements for “the uplift and betterment of the Colored People,” and later in history President Hamilton Holt vowed to put Hungerford “under our academic wing.”[7]

A few notable supporters of Hungerford School at Rollins: Nathalie Lord, William Blackman, William O’Neal, George Morgan Ward, and Hamilton Holt.

At a meeting in 1932, Rollins’ Hungerford School Committee discussed the various needs and fund-raising efforts for Hungerford. The Committee also expressed concern about the “good deal of opposition by west coast counties to the repeal of the law making it a minimal offense for a white person to teach in a negro school.”[8] Then with the assistance of the American Civil Liberties Union, Professor Edwin Clarke, of the Rollins Sociology Department, volunteered to be arrested to contest the segregation law in Florida court. However, out of fear of racial violence from local KKK members, Hungerford was reluctant to be a part of such a blatant legal challenge.[9] Soon after, the Hungerford School Committee was expanded into the Rollins Race Relations Committee, which sought to improve relationships between African American and White residents in Central Florida. After the brutal lynching of Claude Neal in Marianna, Florida, the Committee drew up strong resolutions to condemn the racially motivated crime. Signed by Hamilton Holt, four deans, and 450 students, faculty, and staff members, the letter was sent to national media outlets like President Roosevelt, Governor Sholtz, Florida congressmen, and Orange County legislators.[10]

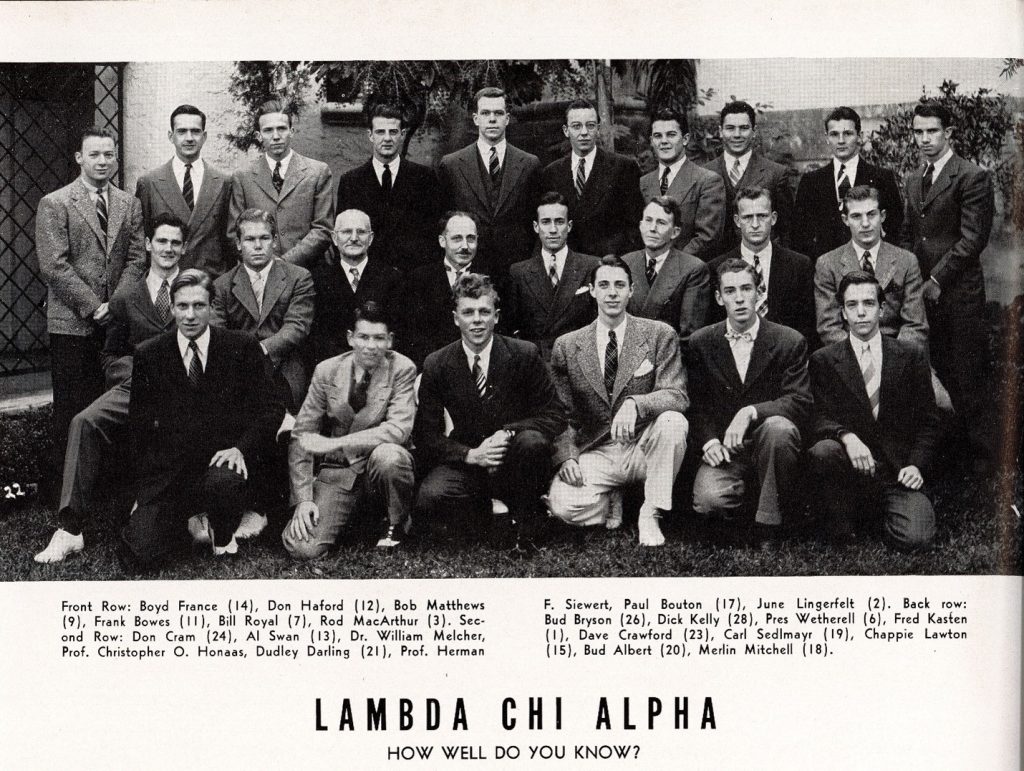

Rollins cherishes its historical link with Zora Neale Hurston, proud daughter of Eatonville, Florida and famed African American author and anthropologist. In the 1930s, Hurston dedicated two of her novels to Rollins professors: Edwin Grover, Professor of Books who helped her literary career with manuscript recommendations, and Robert Wunsch, Professor of Theatre who facilitated two African American folklore performances inspired by Hurston at Rollins in 1933 and 1934.[11] Royal France, Professor of Economics at Rollins, also had a friendship with Hurston. She once had dinner and spent a night at France’s home, causing quite a kerfuffle in the conservative Winter Park community.[12] A lawyer by training, France joined the Rollins faculty in 1929. With years of business experience, he sympathized with the struggles of working-class people. As an idealist and social activist, France supported the causes of those persecuted in America including minority groups. Serving as president of the Florida Socialist Party, he was an outspoken opponent of the segregation system and of police brutality against African Americans.

In the summer of 1939, France’s son, H. Boyd France ’41, and Boyd’s friend, J. Roderick MacArthur ‘42, were arrested in the African American neighborhood of Parramore for violating the Florida vagrancy laws, the state statutes designed to enforce the separation in the Jim Crow South. France bravely fought the Orlando Police Department for their discriminatory measures and civil right violations. He confronted Orlando Chief of Police William H. Smith, and filed a grievance with Attorney General Frank Murphy, in which he claimed that the vagrancy ordinance violated the Bill of Rights, and demanded the U.S. Justice Department to investigate.[13] Unfortunately, the newly created Civil Rights Unit had no legal authority to redress his complaint.[14] Despite the setback, France remained unwavering in his support for civil liberty and justice and devoted his life to defending those wrongly accused in the Red Scare crusade of the early 1950s. Meanwhile, this confrontation with law enforcement in the segregated South likely had a profound impact on Rollins student J. Roderick MacArthur. After having a successful business career, he established the J. Roderick MacArthur Foundation and the MacArthur Justice Center to support civil rights and civil liberty causes in the United States. In 1984, for his outstanding work supporting human rights causes, the American Civil Liberties Union presented MacArthur the Roger Baldwin Award.[15]

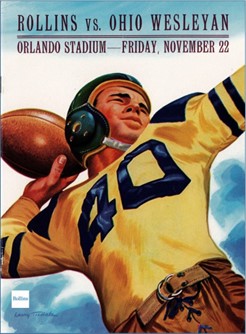

In the following decade there was another defining moment in college history in terms of race relations — the Rollins-Wesleyan football game of 1947. As noted earlier, Rollins faculty and students supported progressive race relations long before other members of the Winter Park community. The 1947 scheduled homecoming football game between Rollins College and Ohio Wesleyan University (OWU) set Rollins’ racial progressivism on a direct collision course with the overwhelming white supremacy in segregated Central Florida. Since state law still prohibited mixed participation in any educational programs, a so-called gentlemen’s agreement allowed white southern leaders in higher education to maintain the color line on college athletic fields. In November 1947, upon learning that the OWU team included an African American freshman player and out of fear that potential violence by local Klan members would set back social progress in the South, President Holt decided to cancel the event despite his own more progressive view of race relations.[16]

Stepping forward at the Time of the Crises

Although Holt claimed that his decision was in the best interest of Rollins and its ideals “not to precipitate a crisis that might and probably would promote bad race relations,”[17] many students and faculty members stood up firmly to voice their opposition to his decision. The Sandspur staff issued an editorial strongly condemning Holt’s edict: “To allow important policies to be determined by our environment is to sink into ineffectual romanticism and to avoid our intellectual responsibilities. And we must face those responsibilities, or face the fact that we can no longer call ourselves a liberal college… We must not be blinded by the possibility of violence to the larger possibilities for good in a given situation. We must not sink into existences of quiet desperation, and forget when to stop compromising.”[18]

Among multiple open letters of protest to the decision was one written by Martin Dibner ’48, a veteran student of WWII. After posting a series of questions to Holt, Dibner proclaimed: “We talk modestly of fair play and the spirit of the thing. The same spirit that carried White man and Black alike to war, where shrapnel never heard of race prejudice… In times like these, when hate rides high and intolerance plagues the world, no institution of learning should compromise.”[19] Deeply moved by community responses from Dibner and many others, Holt soon felt remorse about his decision and began to take actions that he felt could correct his misstep. Specifically, in 1948, Holt awarded the Rollins Decoration of Honor to Susan Wesley, a long-time and beloved African American housemaid for the Rollins women’s dorms. In 1949, before his retirement, Holt gave an honorary Doctor of Humanities degree to Mary McLeod Bethune, the famed African American educator and civil right leader.[20]

Rollins had its fair share of political turmoil over the years. One such incident was what has become known as “The Rice Affair” of 1933. After a successful Curriculum Conference led by famed American philosopher and educational reformer John Dewey in 1931, many were drawn to Rollins because of its rising reputation as a national leader in progressive experimentation. As one of the original “Golden Personalities,” John Rice was a Classics professor hired by President Holt in 1930. A brilliant academic, Rice was a very controversial instructor who often held class discussions on “sex, religion, [and] unconventional living” instead of teaching Greek and Latin.[21] His open hostility toward Greek life and religious groups also upset members of the college community and other residents of Winter Park. However, when Holt decided to fire Rice, his termination generated an upheaval. A number of the students, including campus leaders such as George Barber, editor of the Sandspur, and Nathaniel French, president of the student body, reacted strongly against Rice’s dismissal.[22] While they may not agree with the radical positions held by Rice, a group of faculty and students were very concerned on how the matter was handled by Holt and viewed the Rice dismissal as a serious setback for innovative education. Students and faculty debated the topic in the classrooms and held community forums where they openly criticized President Holt. Professor Alan Tory even gave a speech entitled “The Faith that Rebels” in the Knowles Memorial Chapel, where he spoke of the need to struggle against authoritarian decisions.[23]

Throughout the crisis, a small group of faculty members refused to make a loyalty pledge to Holt when this was demanded by the President. Notable among them was Ralph Lounsbury, Holt’s Yale classmate and a well-respected faculty leader on campus. As a friend, Lounsbury passionately pleaded his case to Holt: “I have gone and shall doubtless continue to go upon the supposition that loyalty does not call for mere subserviency or for clothing an honest expression of opinion. College professors who are willing to surrender lightly the thing which is very fundamental to their profession–namely their mental integrity–are not apt to be of any value to Rollins.”[24] Though a socially progressive liberal, in the case of the Rice Affair Holt used an iron fist to tout shared balances of power like faculty governance, faculty-administration collaboration, and consensus building.[25] In the end, eight faculty members were dismissed or resigned, making up almost one-fourth of the faculty at that time. Furthermore, Rollins was censured by the American Association of University Professors for violating AAUP principles for academic freedom and tenure.[26] Ultimately, the faculty that left Rollins would establish Black Mountain College in North Carolina, starting a new chapter of experimental learning in the history of American education.

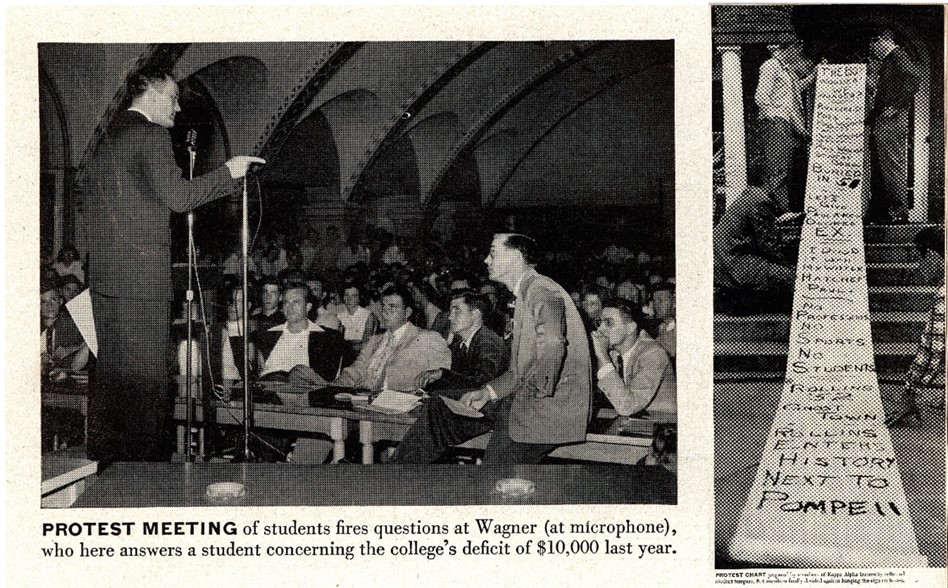

The Wagner Affair was another watershed moment in the Rollins history. After the 25-year tenure of the Hamilton Holt administration, Paul Wagner was named the ninth president of Rollins in 1949. A former executive at Bell & Howell Corporation and an innovator in audio-visual education, Wagner was a young, dynamic individual, a “Boy Wonder” as depicted by Collier’s magazine.[27] With a strong belief that emerging instructional technologies would enable more efficient learning, Wagner was determined to make Rollins a national model in audio-visual education. However, his approach was resisted by many faculty and students, who saw it as impersonal and a departure from Holt’s legacy of individualized education. More significantly, with his background in business, Wagner tended to view the College as an enterprise rather than a community of learners. After he became president, Wagner first eliminated the costly football program. Then after the outbreak of the Korean War, he developed a doomsday view on American higher education. In March 1951, when Rollins was projected to run into a serious deficit with at least 30% decline in enrollment in the coming academic year, Wagner, with the support of the Board of Trustees, terminated a group of nineteen professors and four adjunct instructors, which amounted to one-third of the total faculty, many of them long-serving, tenured members of the College.[28]

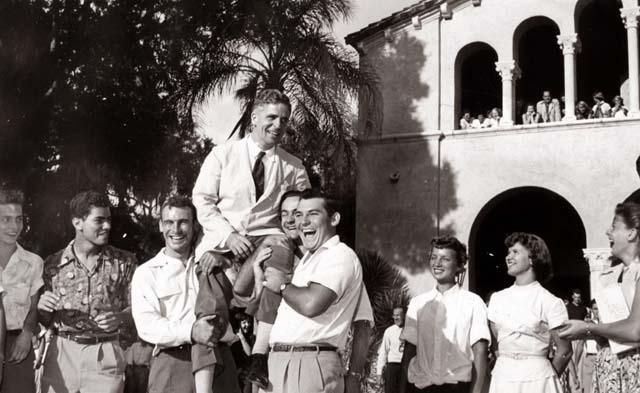

Members of the Rollins community again stepped forward in a moment of the crisis. The massive dismissals threw the campus into turmoil. Students and faculty held various meetings, marches, and demonstrations demanding explanations and an alternative course of action from Wagner. Shocked by his pronouncement, people felt Wagner’s unilateral decision defied the cherished value of the democratic community at the core of the Rollins tradition. At a meeting on Sunday, March 11, 1951, faculty passed a unanimous motion demanding “the president right here and now rescind the dismissals and begin work with the faculty and students on alternative proposals.”[29] However, with the confidence that he would have the support from the Board of Trustees, Wagner stood firm. His stubbornness united faculty and students into a solid front of opposition, which eventually led to a non-confidence resolution for Wagner’s leadership. As Professor Nathan Starr bravely proclaimed: “The faculty feels that the present situation within the college has been handled improperly and could have been avoided. Our confidence in the presidential leadership has been irreparably damaged.”[30] Meanwhile, a student committee began meeting with their faculty counterpart and called meetings almost daily in the Student Center. Through its weekly editorials, the Sandspur passionately expressed student attitudes of the emergency situation, accusing Wagner of breaking his promise and of taking Rollins “down the rocky road of ruin.”[31] Finally, on May 10, 1951, a majority of the students walked out of classes and refused to return until Wagner resigned. The unified actions by students and faculty finally convinced the Board to reverse course, and instead elect Hugh McKean as acting president of the College three days later. When he emerged from an all-college meeting held in the Annie Russell Theatre, the students spontaneously lifted Hugh McKean on their shoulders and walked with him through the campus shouting cheers of victory.

Advocating for the Integration, Belonging, and Diversity

Fred McFeely Rogers ’51 ’74H, the creator and celebrated host of the children’s television program Mister Rogers’ Neighborhood, is one of Rollins’ most beloved alumni. After transferring to Rollins from Dartmouth in 1948, Fred Rogers excelled academically and graduated with distinction, earning a degree in music composition in 1951. While studying at Rollins, Fred Rogers developed progressive viewpoints on race relations in America and was involved in philanthropic work to make a difference in the local community.[32] A recognized student leader at Rollins, Fred Rogers served as chair of the Rollins Inter-Faith and Race Relations Committee. Under his leadership, this Rollins student group collected and sorted books for the historically black Eatonville community, raised funds for the DePugh Nursing Home for African Americans on the West Side of Winter Park, partnered with a local electric company to have new lighting installed at the Hannibal Square Library, hosted a Thanksgiving party for dozens of African American kids, made Christmas presents for local needy families, attended a cultural program at Bethune-Cookman College (an HBCU in Daytona Beach), and organized the 7th annual interfaith event featuring the Hungerford School Choir in the Annie Russell Theatre.[33]

While many like Fred Rogers worked diligently to improve race relations, the social focus of American education began to shift. As the growing calls for equal access to education began to have impact, progressive Americans began to advocate for the full integration of the education system in the South. Finally in 1954, the U.S. Supreme Court ruled that “separate educational facilities are inherently unequal,” and therefore violated the Fourteenth Amendment of the U.S. Constitution.[34] Despite the unanimous court ruling, many conservatives, holding on to the notion of the idyllic “Old South” and their way of living, vehemently resisted the integration. It was not until the passage of the Civil Rights Act in 1964 that the rest of the segregated schools in the American South began to integrate. Rollins was one of them, and one alumna played a key role in the process, in addition to many others who worked tirelessly towards the goal of inclusion.

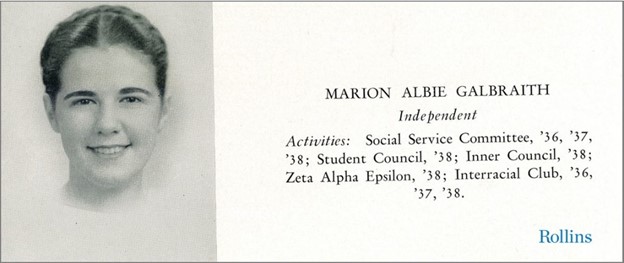

Marion Galbraith Merrill (1914-2012) ’38 was a member of the Student Council, the Social Service Committee, and the Interracial Club while a student at Rollins.[35] She served briefly as an executive assistant of the College before moving away with her husband to work as a research assistant in the Washington D.C. region. A social justice advocate, Merrill was active in the Civil Rights Movement. She attended the “I Have a Dream” rally in front of the Lincoln Memorial and marched with Martin Luther King Jr. to Montgomery, Alabama.[36] In 1964, frustrated by the lack of social progress of her alma mater, she wrote a letter to the school administration demanding that Rollins take concrete steps to integrate its student body.[37] In a letter to Alfred J. Hanna, Merrill threatened that she was in communication with the U.S. Commission on Civil Rights and would report on the school’s inaction if matters did not resolve in timely fashion.[38] Facing the real risk of losing federal grant funding, in his rely to Merrill, President Hugh McKean hastily pointed out that the Rollins admission policies and process were not to be discussed with outside parties, but race played no role in the acceptance of any applicants.[39] Finally, in the fall of 1964, Rollins enrolled John Mark Cox, Jr., the first African American student in the college’s history.

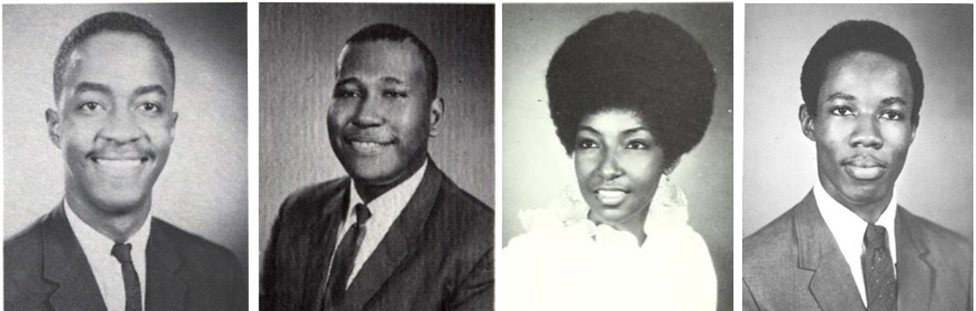

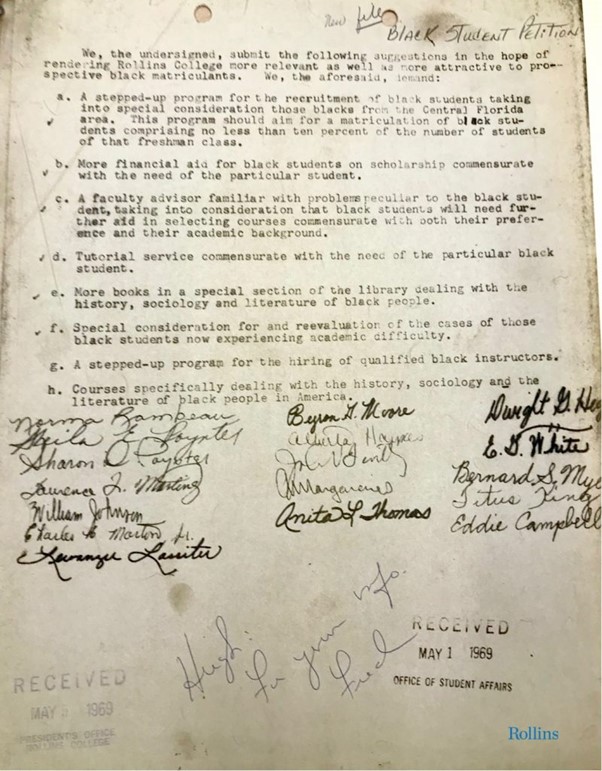

In 1965, Della Dunn became the first African American female enrolled at Rollins, and she was followed by William Johnson, Lewanzer Lassiter, Branda MoMillon, and Bernard Myers in 1966. The enrollment of Black students increased to nine in 1967, fifteen in 1968, twenty in 1969, and by 1970 Rollins had its first Black graduates.[40] Despite the gradual increase in numbers, these trailblazing students still had to face the legacy of a segregated school and deal with ever present underlying racist attitudes. While a few struggled and remained silent, many of these students became active on campus and spoke out about their experience and share their journey with the student newspaper Sandspur and Rollins Alumni Record. In 1969, “in the hope of rendering Rollins College more relevant as well as more attractive to prospective black matriculant,” seventeen students signed a public petition that recommended:

- A stepped-up program for the recruitment of Black students,

- More financial aid for Black student scholarship,

- Recruitment of qualified Black professors,

- Courses in history, sociology, and literature related to African American experiences,

- And an increase in library collections of the same subject areas.[41]

This open letter brought some positive changes. For example, in 1971, Eleanor Mitchell Thomas of Political Science became the first African American faculty member in the college history; during the same year, Alzo J. Reddick was appointed the first Black administrator at Rollins.[42]

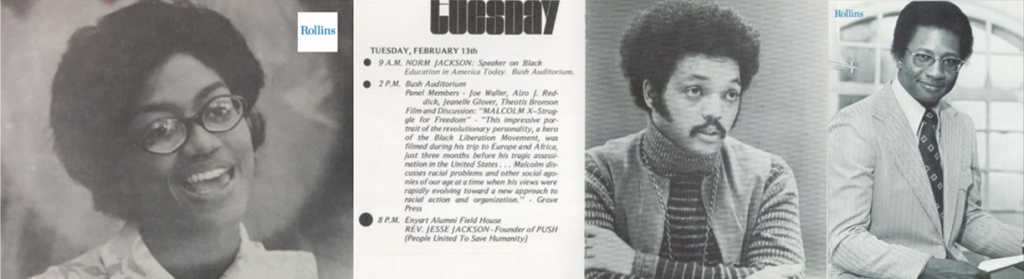

To change institutional culture, African American students organized the Black Student Union (BSU) and launched the annual tradition of Black Awareness Week in the early 1970s. According to its Charter, the BSU was established to “create a relevant social and academic atmosphere for Black students, foster a unity between Black students on campus and the surrounding community, plan programs and activities emphasizing the cultural achievement of Black people, and provide Black students with positive symbols and values that are essential to the development of the whole individual.”[43] Since its founding, the BSU has played an active role in promoting the awareness, understanding, appreciation, and development of multiculturalism at Rollins. Its signature annual program was Black Awareness Week, and in 1973 Reverend Jesse Jackson was a keynote speaker.[44] By featuring Black speakers, artists, and musicians, as well as cultural events such as films, food, fashion, and worship, Black Awareness Week was designed to not only promote pride in African American heritage, but also enlighten the larger Rollins community, facilitate congenial race relations, and provide a platform for the free exchange of ideas.[45]

Fighting for Equality, Freedom of Expression, and Social Justice

With monumental efforts by devoted students, faculty, staff, and administrators, Rollins began to develop into a more diverse community of learners. However, prejudice still persisted in many ways in the area of gender equality. A co-educational institution since 1885, Rollins has traditionally enrolled more women than man. In fact, the first graduating class consisted of only two female students. Nonetheless, with its location in the conservative South, Rollins always had much stricter regulations for female students than for their male counterparts. Rollins women were expected to “be a lady at all times.”[46] However, as time passed more women began to advocate for gender equality. When only females were required to remain on campus during the four-day Fiesta weekend, women students raised the question of fairness to the administration and strongly objected the college policy.[47] Sandspur also began to run stories of gender-based injustice at Rollins, especially after the passage of the Title IX Amendments of 1972. For instance, the open letter written by Patricia Loret de Mola ’78 provided multiple examples of sex-based discriminations on campus and called for wider campus support in the “fight for equality.”[48]

Muriel Fox attended Rollins during 1944-46, where she studied under progressive professors such as Royal France and Nathan Starr and worked for both the Rollins Sandspur and Flamingo. After her college education, Fox pursued a career as a professional writer. However, when she was told that one of the largest public relation firms did not hire women writers, she decided to change the business climate for women.[49] To counter discriminations against women everywhere, Fox and other feminist leaders co-founded the National Organization for Women (NOW) in 1966, now the largest feminist organization in the United States. In 1967, she also wrote an essay for the Rollins Alumni Record enthusiastically advocating for the “full equality for women in truly equal partnership with men.”[50] With endeavors by Fox and many others, the Women’s Liberation Movement started to take root at Rollins.[51] In 1974, Rollins began to offer women’s study courses in the School of Continual Education. By the early 1980s, under the leadership of Professor Rosemary Curb, and with the establishment of the Rollins Organization for Women (ROW), Rollins finally adopted a gender-equity policy, and the Women’s Studies Program became an integral part of the college curriculum.[52]

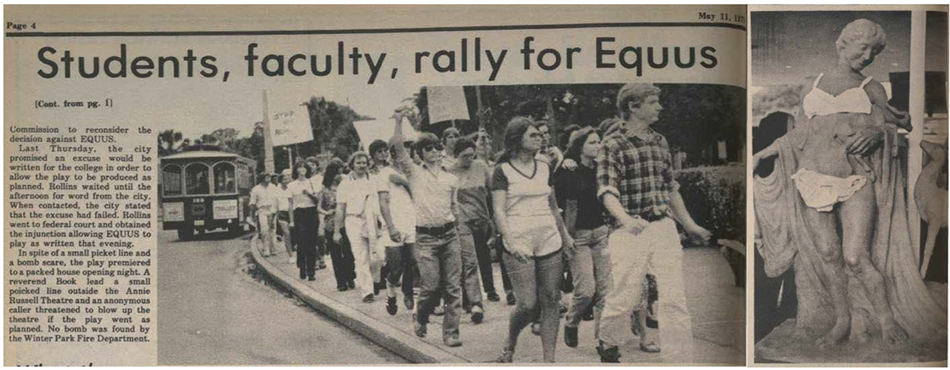

Another high-profile and protested controversy on campus was the first performance of Equus. In May 1979, after some community members learned that the upcoming Rollins play, Equus, would contain a few minutes of nudity on the stage of the Annie Russell Theatre, eighteen residents made complains to the Winter Park Police Department. According to Sec. 62-121 of Code of Ordinance of the City of Winter Park (Code 1960, § 18-14): “It should be unlawful for any person within the corporate limits of the city to be found in a state of nudity.”[53] City officials threatened to arrest the play director and student actors if Rollins did not back down and cancel the production.[54] However, even with the potential danger and possibility of criminal persecution, students and faculty took a stand to protect the freedom of expression guaranteed by the U.S. of Constitution.

On May 3, 1979, at a public forum where over 400 students and faculty members gathered, Dr. Arnold Wettstein, Dean of Knowles Memorial Chapel, proclaimed that Rollins would not back down and allow the city commission to govern how Equus should be portrayed. After the rally, a large group of students and faculty marched to Park Avenue. Led by Margaret Peg O’Keefe, Theatre Arts major ’81, they put a bra on top of the nude statue in front of the City Hall to highlight the hypocrisy and absurdity of the incident. Two students, Jody K. Kielbasa ’80 and Robert Klein ’79, presented a public petition to Winter Park City Manager David Harden.[55] Meanwhile, on the same afternoon, President Thaddeous Seymour had to seek an emergency injunction in the federal court to ensure the inaugural show would take place in the evening.[56] Despite a bomb scare and a picket line from some local community members, on the opening night, May 3, 1979, the play premiered successfully to a packed audience.

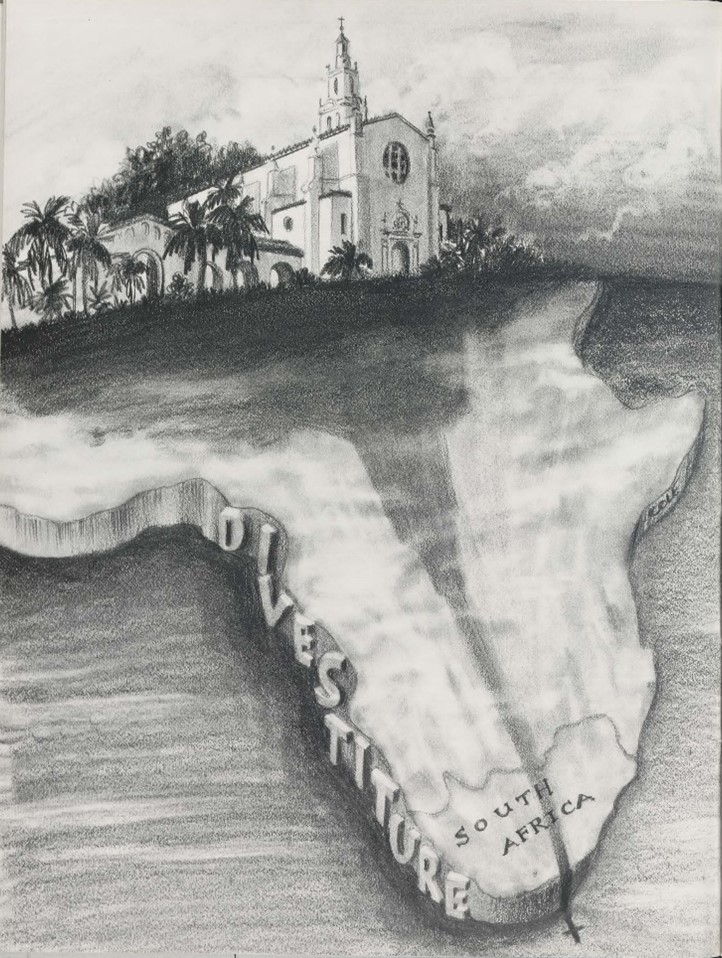

Striving to be global citizens and responsible leaders, Rollins students have fought against discriminations both near and far. One such a notable case was the student-led anti-apartheid rally held in the Mills lawn in 1985. First implemented in the 1940s, apartheid was a legacy system of institutionalized racial segregation that still remained in South Africa in the mid-1980s. As the College geared up its efforts for the centennial celebration, a group of socially conscious and politically active students decided to take a strong stand to condemn the racial discrimination of apartheid on the other side of the world. Specifically, they requested that Rollins divest from corporations that did not honor the Sullivan Principles. Introduced by Rev. Leon Sullivan, an African American minister and a member of the Board of General Motors, the Sullivan Principles consisted of six distinct ideas that signatories were supposed to work towards non-segregation, equal employment practices, equal pay, employee education, support for Black management, and social programs.

In the 1980s, the issue of investment in South Africa was big on all campuses. In his 2009 oral history interview, President Emeritus Seymour recalled his experience of facing student demonstrations while holding the Board of Trustees meeting on November 1, 1985. “The most vigorous protests were campuses where they would build shanties out of corrugated cardboard. The students would live in them and had signs and so forth. And our students did that here in front of Mills, and Mills of course is where the trustees were meeting. So, the Friday before our Centennial, we had shanties—I’m not very proud of this—shanties in front of Mills. We had our trustees walking by them, being aware of the concern of students. And the agenda item was whether Rollins would adopt the Sullivan Principles.”[57] While the board members were unanimous in their oppositions to racism and apartheid, they were divided on how to better respond. After some “painful discussions” and a passionate plea from President Seymour, the Board of Trustees finally passed a resolution of divestiture of investments in corporations not signing the Sullivan Principles.[58]

Conclusion

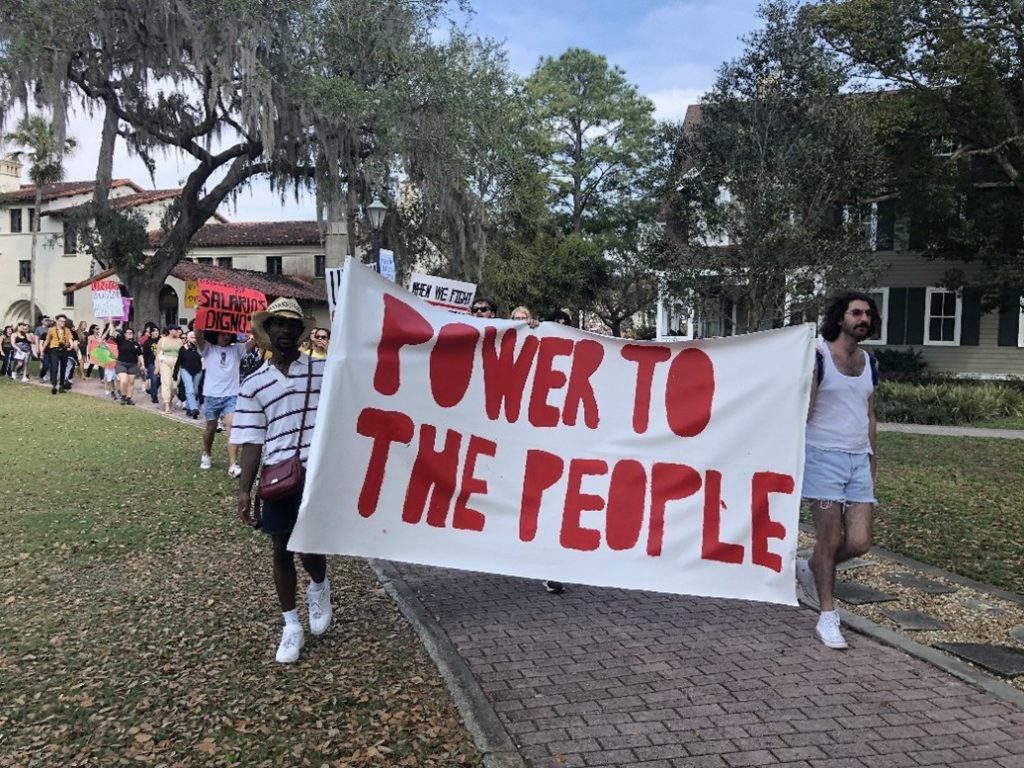

This article only summarizes a few notable cases of political activism at Rollins in the twentieth century. Readers should know that, in addition to the events outlined here, there were multiple war protests at Rollins over the years, some of which were recently highlighted in a student essay.[59] It should also be noted that a great deal of student civil rights endeavors may never make it to the official institutional history, as they were not well documented and did note become a part of campus records. Indeed, there are undoubtedly many such moments which are still yet to be explored. More significantly, this history is still being written as we speak. Echoing the College’s mission of liberal arts education and its promise of global citizenship and responsible leadership, the current institutional priorities surrounding DEIB initiatives and those related to the global United Nations Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) are two more recent examples of the bridge between the academy and social activism at Rollins.

Be the Change you want to see in the world. Throughout college history, frustrated by injustice and wrong doings, unwilling to accept compromise, and refusing to remain silent, many brave people – students, alumni, faculty, and administrators alike — have taken a stand to make a difference. They have spoken out against all forms of discrimination, organized protests to denounce the immorality of racial segregation, and held sit-ins and peaceful assemblies to condemn unfair laws, policies, and regulations. And there is still much to be done today in opposing systemic racism, defending our constitutional rights, fighting for women’s’ equality, protecting our environment, or promoting diversity and inclusion. Through continued diligent efforts, a group of socially conscious faculty, staff, students, and alumni are taking the lead in making Rollins a better place for our current and future community of learners.

[1] Mary Duncan France. “‘A Year of Monkey War’: The Anti-Evolution Campaign and the Florida Legislature.” The Florida Historical Quarterly 54, no. 2 (1975): 156–77. http://www.jstor.org/stable/30147335.

[2] “Protest in Florida on Anti-Darwin Bill: President Holt and Faculty of Rollins College Send Plea to Governor and Legislature. For Freedom of Teaching Pending Act Forbids Contradicting Biblical Story of Creation — Must Seek the Truth, Holt Declares.” New York Times, April 30, 1927, 3. http://ezproxy.rollins.edu:2048/login?url=https://www.proquest.com/historical-newspapers/protest-florida-on-anti-darwin-bill/docview/104157012/se-2?accountid=13584.

[3] Ibid.

[4] Warren Kuehl, Hamilton Holt: Internationalist, Journalist, Educator (Gainesville, FL: University of Florida Press, 1960), 223-25.

[5] “Dr. Holt Makes Strong Plea for Free Thought.” “Rollins Faculty Takes Firm Stand Against Proposed Evolution Bill: Is First College to Express Its Attitude.” Rollins Sandspur, May 6, 1927. https://stars.library.ucf.edu/cfm-sandspur/2566.

[6] “Anti-Evolution Bill Is Passed by House in Florida, 67 to 24.” New York Times, May 19, 1927, 1; France, 1975, 169.

[7] Wenxian Zhang, “Learning by Doing in the Segregated South: The Robert Hungerford Normal and Industrial School for African Americans in Central Florida.” Phylon: The Clark Atlanta University Review of Race and Culture 60:1 (summer 2023), 63-90. https://scholarship.rollins.edu/as_facpub/264/.

[8] Orpha Hodson, “Hungerford School Committee Minutes, May 19, 1932.” Florida Vertical Files, Rollins College Archives, Winter Park, Florida.

[9] Sprague, Miriam. 1932. “Hungerford School Committee Minutes, October 29, 1932.” Florida Vertical Files, Rollins College Archives, Winter Park, Florida.

[10] Edwin L. Clarke, Rollins Sociological News 2:1 (1934). Florida Vertical Files, Rollins College Archives, Winter Park, Florida.

[11] Maurice J. O’Sullivan, Jr., and Jack C. Lane, “Zora Neale Hurston at Rollins College,” in Steve Glassman and Kathryn Lee Seidel (eds.), Zora in Florida (Gainesville, FL: University Press of Florida, 1991), 130-145.

[12] Royal France, My Native Grounds (New York: Cameron, 1957), 75. https://scholarship.rollins.edu/as_facpub/115/.

[13] Jack C. Lane, “The Case of the ‘Embryo Artist’ and Vagrancy Laws in Segregated Orlando, 1939.” eFHQ https://chdr.cah.ucf.edu/efhq/lane.html.

[14] John Rogge to Royal France, August 4, 1939. 45E Royal Wilbur France Faculty File, Rollins College Archives, Winter Park, Florida.

[15] Kathleen Teltsch, “J. Roderick Macarthur Is Dead; Encouraged Awards for ‘Genius.’” New York Times, December 16, 1984, 44.

[16] Wenxian Zhang, Raja Rahim and Julian Chambliss, “Race and Sport in the Florida Sun: The Rollins/Ohio Wesleyan Football Game of 1947.” Phylon 56:2 (2019): 59-81.

[17] “Remarks by Hamilton Holt at the Annie Russell Theatre.” November 28, 1947. Rollins College Archives, Winter Park, Florida.

[18] “Editorial.” Sandspur 52:9 (December 4, 1947), 2. https://stars.library.ucf.edu/cfm-sandspur/795.

[19] Martin Dibner, “An Open Letter to Dr. Hamilton Holt.” Sandspur 52:9, 2. (December 4, 1947), 2. https://stars.library.ucf.edu/cfm-sandspur/795.

[20] Wenxian Zhang, Raja Rahim and Julian Chambliss, “Race and Sport in the Florida Sun: The Rollins/Ohio Wesleyan Football Game of 1947.” Phylon (1960-) 56, no. 2 (2019): 59-81.

[21] “Rollins College versus The American Association of University Professors “Part II: The Grounds for Dismissal, An Analysis of the Evidence.” Rollins College Bulletin 2: no. 29 (December 1933).

[22] Jack C. Lane, “Chapter 06: A College in Crisis (The Rice Affair) 1933.” Rollins College: A Centennial History (Winter Park, FL: Rollins College, 2017). http://scholarship.rollins.edu/mnscpts/6.

[23] Ibid.

[24] Lounsbury to Holt, March 16, 1933. Rollins College Archives, Winter Park, Florida.

[25] Randy Noles and Ed Gfeller, “Talent for Tumult.” Winter Park Magazine (Summer 2016), https://winterparkmag.com/2016/06/21/talent-for-tumult/.

[26] Lane, Rollins College: A Centennial History, Ch. 6, 22; American Association of University Professors, “Report on Rollins College.” Bulletin of the AAUP 19:7 (November 1933), 429.

[27] Hartzell Spence, “Education’s Boy Wonder.” Collier’s Magazine (January 13, 1951).

[28] Jack C. Lane, “Chapter 08: A Legacy of the Holt Era (The Wagner Affair), 1949-1952.” Rollins College: A Centennial History (Winter Park, FL: Rollins College, 2017). http://scholarship.rollins.edu/mnscpts/4.

[29] Ibid.

[30] Randy Noles, “The Wagner Affair.” Winter Park Magazine (Spring 2017), https://winterparkmag.com/2017/04/10/the-wagner-affair/.

[31] “Editorial: Rocky Road to Ruin.” Rollins Sandspur 55:20 (April 6, 1951), 2. https://stars.library.ucf.edu/cfm-sandspur/881.

[32] Chantel Tattoli, “The Radical Mister Rogers.” The Paris Review, December 3, 2019. https://www.theparisreview.org/blog/2019/12/03/the-radical-mr-rogers/.

[33] Fred Rogers, “Report for 1950-51.” Rollins College Archives, Winter Park, Florida. https://www.jstor.org/stable/community.39301225.

[34] Brown v. Board of Education, 347 U.S. 483. https://supreme.justia.com/cases/federal/us/347/483/.

[35] The Tomokan Yearbook 1938 (Winter Park, FL: Rollins College). https://scholarship.rollins.edu/tomokan/78.

[36] Marion (Galbraith) Merrill St. Johnsbury Academy Class of 1933. https://www.nekg-vt.com/files/stj/obits/Academy/193x/Marion-Merrill.php.

[37] Rachel Walton, “Pathway to Diversity: The History of Race Relations at Rollins: A Brief Overview from the Archives, Part Two (1951-Present).” From the Rollins Archives, https://blogs.rollins.edu/libraryarchives/2021/02/26/pathway-to-diversity-the-history-of-race-relations-at-rollins-a-brief-overview-from-the-archives-part-two-1951-present/.

[38] Merrill, Marion Galbraith. Alumni Files. Rollins College Archives, Winter Park, Florida.

[39] President Hugh McKean to Mrs. Horace S. Merrill, February 1, 1965. Rollins College Archives, Winter Park, Florida.

[40] Tony Layng, “Black Students at Rollins.” Rollins College Alumni Record (1970:2), https://www.jstor.org/stable/community.38481960.

[41] “Rollins’ Policy Regarding African Americans and Minorities in the 1960s and 1970s.” Pathway to Diversity: Rollins Digital Collections, https://www.jstor.org/stable/community.38482020.

[42] “A Talk with Eleanor Thomas.” Sandspur: Rollins College Weekly Magazine 78:4 (October 25, 1971). https://stars.library.ucf.edu/cfm-sandspur/1404.

[43] Constitution of the Black Student Union of Rollins College, Article I, Section II, 1970-1971. Rollins College Archives, Winter Park, Florida. https://www.jstor.org/stable/community.39301370.

[44] “Black Awareness Week Program, 1973.” Pathway to Diversity: Rollins Digital Collections, https://www.jstor.org/stable/community.39301325.

[45] “BSU Open Meeting Flyer, 1972.” Rollins Digital Collections, https://www.jstor.org/stable/community.39301371.

[46] Darla Moore, “Be a Lady at All Times: Rules for Rollins Women, 1961-62.” From the Rollins Archives, https://blogs.rollins.edu/libraryarchives/2012/10/08/be-a-lady-at-all-times-rules-for-rollins-women-1961-1962/.

[47] Ibid.

[48] Pat Loret de Mola, “Women Need ‘a Fair Chance.’” Sandspur 85:12 (May 11, 1979), 3. https://stars.library.ucf.edu/cfm-sandspur/1538.

[49] Muriel Fox and Wenxian Zhang, “Interview with Ms. Muriel Fox: Rollins Alumni, Executive Vice President of Carl Byoir and Associates, & Co-Founder of NOW” (2010). Rollins Oral Histories. https://scholarship.rollins.edu/oralhist/7.

[50] Muriel Fox Aronson ’48, “A Fair Shake for the Fair Sex.” Rollins Alumni Record (October 1967), 6-7. https://scholarship.rollins.edu/magazine/227/.

[51] Karin Kest, “Women’s Lib Hits Rollins.” Sandspur 77:16 (February 19, 1971), 2-3. https://stars.library.ucf.edu/cfm-sandspur/1392.

[52] Mickayla Grasse-Stockman, “The Origins and Evolution of Women’s Studies at Rollins College, 1980-2000.” From the Rollins Archives, https://blogs.rollins.edu/libraryarchives/2021/06/09/the-origins-and-evolution-of-womens-studies-at-rollins-college-1980-2000/.

[53] “The Ordinance.” Sandspur 85:12 (May 11, 1979), 4. https://stars.library.ucf.edu/cfm-sandspur/1538.

[54] “Mary Ann Campbell, “No Nude Acting, Winter Park Says.” Sentinel Star, May 1, 1979, 1.

[55] “Equus Premieres as Planned!” Sandspur 85:12 (May 11, 1979), 1-2, 4. https://stars.library.ucf.edu/cfm-sandspur/1538.

[56] Thaddeus Seymour and Wenxian Zhang, “Oral History Interviews with Dr. Thaddeus Seymour, May 25 and June 1, 2005.” Rollins Oral Histories. 26. https://scholarship.rollins.edu/oralhist/26.

[57] Thaddeus Seymour, Wenxian Zhang, Julian Chambliss, and Denise Cummings, “Oral History Interview with President Emeritus Thaddeus Seymour, January 30, 2009.” Rollins Oral Histories. 37. https://scholarship.rollins.edu/oralhist/37.

[58] Bill Wood, “Divestiture: Rollins Takes a Stand.” Rollins Alumni Record (Spring 1986), 2-4, https://scholarship.rollins.edu/magazine/298.

[59] Liam Taylor King, “‘Fiat Pax:’ Peace, War, and Protest at Rollins, 1938–2003.” From the Rollins Archives, https://blogs.rollins.edu/libraryarchives/2023/09/26/fiat-pax-peace-war-and-protest-at-rollins-1938-2003/.