This student-researched article about this history of peace protests at Rollins College in the face of war is authored by Liam Taylor King and posted in honor of International Peace Day – September 21, 2023.

Rollins College, at eighty acres, comprises a speck of the United States. Yet, as one of Florida’s oldest colleges, founded in 1885, Rollins has borne witness to national change on a massive scale. During highly influential conflicts in the past century—the Second World War, the Vietnam War, and the Iraq War—students, faculty, and staff spoke out and advocated for peace. In all three conflicts, protestors validated their actions through the College’s liberal arts mission, yet each protest developed for itself a unique set of tactics to suit the respective moment’s unique needs. This long history of students grappling with great ideas embodies a time-honored means of implementing the “global citizenship” and “responsible leadership” which our mission demands of us.

Second World War

Even a conflict as total and world-changing as the Second World War sparked domestic protest. Indeed, while there was a massive push for the U.S. to join the war following the bombing of Pearl Harbor in 1941, a large corps of anti-war organizations expressed the necessity of peace. The principal peace activist at Rollins during the World War II period was the college’s president, Hamilton Holt (1925–1949). Holt had a shifting relationship with pacifism throughout the early twentieth century. At times he endorsed a conventional brand of pacifism which entailed an end to all war. At other times he endorsed a radical self-constructed ideology of “world policing,” in which a worldwide air force used military action to prevent the escalation of conflict.[1] In 1938, before the U.S. entry into the war in 1941, Holt began the Fall semester with a convocation of “solemn protest,” an expression of the Rollins community’s unanimity for “race and religious justice.”[2] Moreover, in the same semester Holt erected a monument to peace outside of Lyman Hall. The monument showed a German artillery shell with the invocation:

Pause, passerby and hang your head in shame.

This engine of destruction, torture, and death symbolizes the prostitution of the inventor, the avarice of the manufacturer, the blood-guilt of the statesman, the savagery of the soldier, the perverted patriotism of the citizen, the debasement of the human race.

That it can be employed as an instrument in defense of liberty, justice, and right, in nowise invalidates the truth of the words here graven.

–Hamilton Holt

A seemingly unshakeable pacifist, Holt’s unshaking stance against war was, however, shaken—and it was not the first time. Twenty years earlier, Holt had a moment of uncertainty following the outbreak of the First World War in 1914—partly a pacifist, partly a nationalist, his ideas were muddled and ill-formed. Now, at the onset of the Second World War, Holt eagerly stepped into the war effort. He chaired “the Florida Committee to Defend America by Aiding the Allies,” he fundraised to put cash directly in the hands of the Finnish government, and took advantage of the moment to re-insist on his plans for a world police.[3]

Ultimately, the peace movement at Rollins during the Second World War was far more spiritual than effective. A source of elegant quotations, but not a source of strong, unyielding protest against war. About thirty years later, only the opposite can be said about the student response to U.S involvement in Vietnam.

Vietnam Conflict

The United States government began supporting the anti-communist faction of South Vietnam as early as 1955. However, the massive student resistance for which the conflict is infamous did not arise until around 1965. The expansion of backlash matched the expansion of the war. In 1960 the U.S. government had placed 900 servicemembers in Vietnam, by the end of 1965 the number had grown to 184,300.[4] Both presidents John F. Kennedy (1961–1963) Lyndon B. Johnson (1963–1969) ramped up U.S. military presence in Vietnam, and by 1964 the nation was approaching a tipping point. To field the soldiers necessary for the massive scale of the war effort, the U.S. government instituted a policy of conscription in 1964. Protests against the draft began in 1965, and the scale of protest grew as the draft came to demand more and more young men.[5] Seeing as the people forced to enlist in the U.S. military during this period were entirely young men, college campuses became epicenters of draft resistance, and by 1967, “the draft had become a generational obsession.”[6] Historian Charles DeBenedetti characterized the antiwar movement as equally antiwar and anti-status quo.[7] With so much discontent surrounding them, the upcoming generation eagerly intermixed radical political values into popular culture.

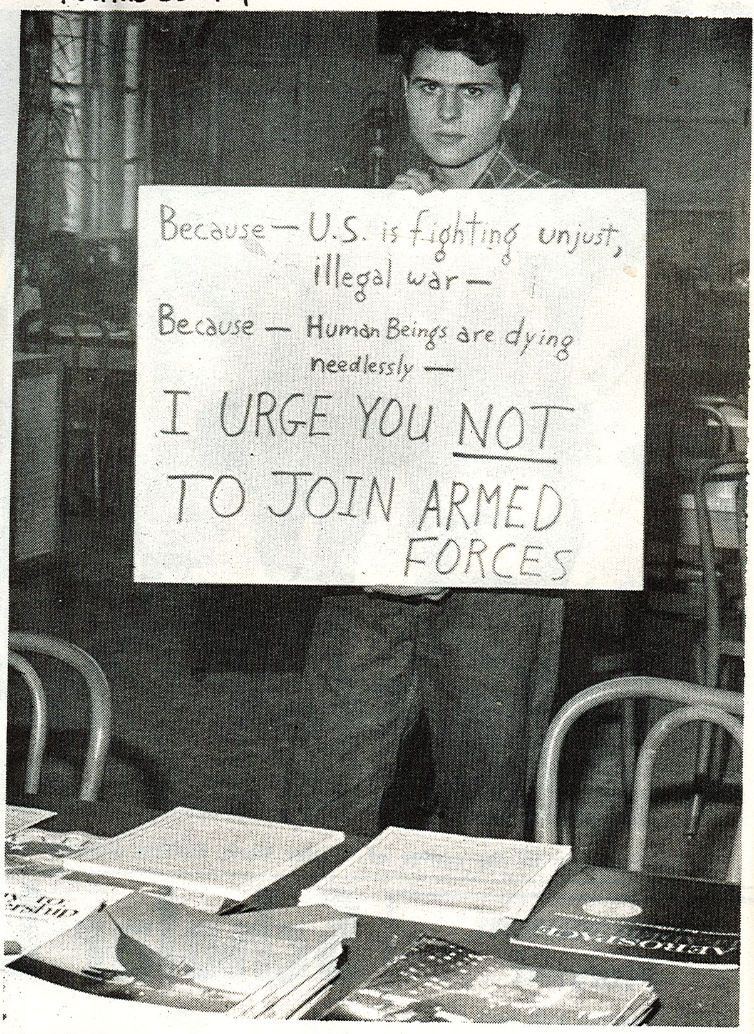

Though the Vietnam War was not the first conflict to spark significant student discomfort, it was emblematic of a shift from a culture of silence to a culture of a grassroots, democratic action culture. [8] At Rollins, this culture shift affected both faculty and staff. Resistance to the Vietnam War on campus relied on a substantial mixture of both student-based protest and institutional protest. Students and faculty alike published articles in the Sandspur condemning the war. In October 1967, Donald James ‘70 approached a recruiting table in the Student Center behind which three U.S. Air Force recruiters sat, stood behind them, and held up a sign which read, “Because—U.S. is fighting unjust illegal war; Because—Human beings are dying needlessly; I URGE YOU NOT TO JOIN ARMED FORCES.”[9]

This sparked a slurry of Sandspur polemics, many accusing James of communism or disloyalty. One such polemic, though, came to James’ defense—authored by Dr. Jack C. Lane. In a letter to the editor Dr. Lane wrote, “for the first time since I came here I saw a Rollins student, despite the scorn heaped upon him, concerned enough to commit himself to something really important.”[10] These individual showings of discontent precede a larger movement against the war.

As public discontent with the war grew, students and faculty collaborated on higher scale protests. In 1969, at least five faculty members and untold numbers of students from both UCF (then called Florida Technological University) and Rollins gathered on Mills Lawn to protest the Vietnam War. Marching two-and-a-half miles around Winter Park, they sang “all we are saying is give peace a chance.”[11] The Sandspur article which captured the moment concluded, “Rollins has just had its first demonstration. Yes, even Rollins.”[12]

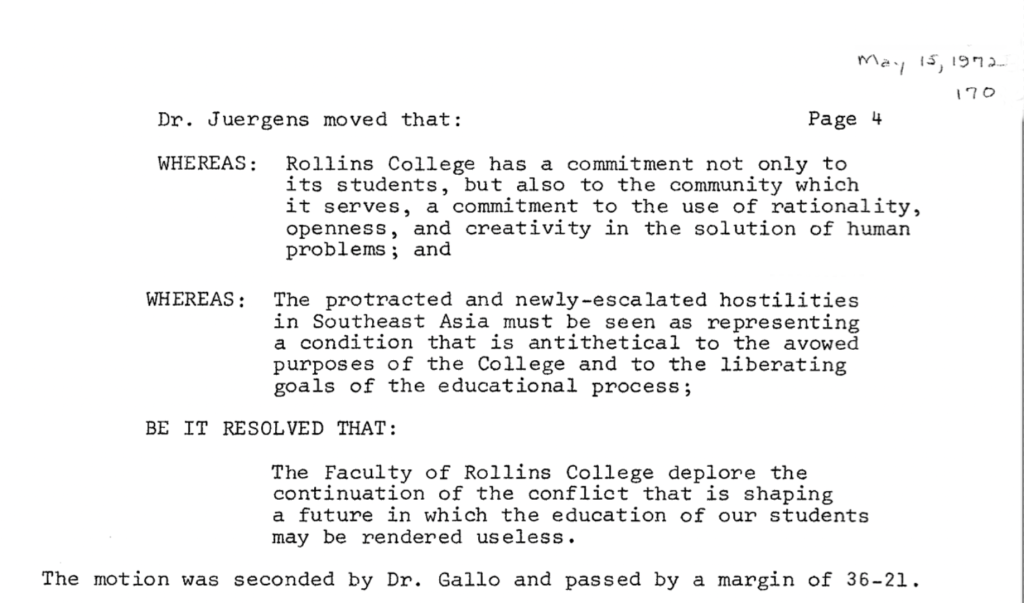

In 1972, the Rollins faculty adopted a resolution condemning “the continuation of the conflict that is shaping a future in which the education of our students may be rendered useless.”[13] Institutional protest like this was necessary to sustain the peace movement from 1965 to 1973. Absent their faculty allies, outraged students would have simply graduated and taken the movement with them. Despite this, it seems undeniable that the students formed the body of the movement. A 1972 memo from History Professor Fred W. Hicks to then-President Jack Critchfield (1969–1978) reported one hundred and twenty students joined by eight to ten faculty members at an anti-Vietnam “rap session.”[14] The strength of the Vietnam protest movement at Rollins was attributable to the collaboration of faculty and students toward the application of Rollins’ liberal arts values to national issues. Such an application would be attempted again, forty years later and in a new millennium, at the outset of war in Iraq.

Iraq War (2003)

The 2003 Iraq War was not the first time the United States military took aim at Iraq, but it was a particularly volatile source for public protest at the beginning of the twenty-first century. Protestors objected to the questionable motives behind the war and the high degree of transnational violence which came to characterize the period. Protestors also challenged the reactionary character of the Bush Administration. While student protests sparked off during the Iraq War, just as they had in the Vietnam War, the scale and nature of these protests were different. The scale of Iraq protest was not significantly smaller than that four decades prior but the scale of pro-war sentiment was significantly higher. On April 2, 2003, a coalition of one hundred and thirty faculty members, students, and staff walked out of classes to protest the Iraq War.[15] The event seemed to mirror the Vietnam protest of 1969 in many ways. Protestors sat in the same grass on the same lawn and listened to the passionate speeches of students and faculty. As for the nature of protest, the principal difference was the degree to which the college administration attempted to quiet student activism.

Where the Rollins faculty had previously ratified a resolution condemning the Vietnam War, the entire Rollins community was now far more divided. A student’s mass email to the campus on March 18, 2003—just two days before the official beginning of the conflict—was a fount for a high degree of public discourse. The email’s author, Nicole Elaine Gilpin ‘03, quoted a strongly anti-war speech to U.S. Senate by Senator Robert Byrd and demanded, “Please don’t keep your head in the sand about this, regardless of what position you take.”[16] Most responses to Gilpin’s email have been lost to time, but for a few.

Through the responses which were preserved, glimpses of other responses can be seen. Some complained of email spam, others of insufficient patriotism, and still others supported the email. One of the most prescient quotations from the surviving responses emerged from Barbara Carson, professor of English, who added:

It strikes me that not only is a discussion like the one going on permissible in this educational environment; it is absolutely necessary. It is, in fact, a duty for us as teachers. If we are silent, I think, we’re betraying our trust. A college’s very existence is premised on the idea that ideas are not to be feared, that what’s really scary is the unthinking acceptance of the ideas of others.

I’m grateful to all those who’ve spoken today. I say, let the ideas flow; let them collide; let’s acknowledge the complexity of the issues we’re facing. Let’s be humble before that complexity, and let’s be open to learning.

And–of course–let’s be respectful of differences and of human feelings, knowing that good, decent, patriotic people can be found on all sides of these controversial issues.[17]

It was clear, however, that campus opinion about peace during the Iraq War was highly divided. In addition to the anti-war rhetoric already mentioned, there were also obvious defenders of armed conflict on campus who used language invoking patriotic nationalism, fears about national security, and general political support for the Bush administration. Examination of the media and other press outlets at this time indicate that there was widespread misinformation about both the Bush administration’s purpose in invading Iraq and the reasons for staying involved in the Middle East arena. Rollins’ relative lack of response to the Iraq War at an institutional level, in comparison to the more unified anti-war actions of the 1970s, may reflect this confusion and also could be emblematic of changes to campus culture by the 2000s. These shifts obviously reflect larger national shifts in popular culture and politics in a post 9/11 America.

The changing nature of student peace protest throughout the history of Rollins shows us the changing nature of Rollins as a place and as a community. Where history is so often written in the narrative of war, this article attempts to write Rollins history in the narrative of peace. Past students and faculty believed the liberal arts were inseparable from peace, and it is the opinion of the author that our narrative of Rollins history must likewise become inseparable from those same values.

Liam Taylor King ’24 is a senior History major at Rollins College. Since July 2023, Liam has served as a Ginsburg Fellow, endeavoring to forge a more diverse, equitable, and inclusive community in Central Florida through educational interventions outside of traditional classrooms. Liam also serves on the Board of Directors of the LGBTQ History Museum of Central Florida and is currently working on a thesis about the queer history of Orlando. Personally, Liam is passionate about Joan Didion’s writings, vintage fashion, and underground music. He plans to pursue graduate school after graduation.

[1] Warren F. Kuehl, Hamilton Holt (Gainesville: University Press of Florida, 1960), 89–106.

[2] “The Convocation of Solemn Protest,” 20J Holt, Hamilton Aclm: Protest Convocation, Hamilton Holt Collection, Rollins College Archives, Olin Library, Rollins College, Winter Park, FL (hereafter RCA); Hamilton Holt, “Holt Urges Students Attend Protest Broadcast,” Sandspur, December 7, 1938.

[3] Kuehl, Hamilton Holt, 249–50.

[4] George Donelson Moss, Vietnam: An American Ordeal 7th ed. (New York: Routledge, 2021), 443.

[5] Moss, Vietnam: An American Ordeal, 242–43.

[6] Moss, Vietnam: An American Ordeal, 242–43.

[7] Charles DeBenedetti, An American Ordeal (Syracuse, NY: Syracuse University Press, 1990), 1-5.

[8] E. M. Schreiber, “Opposition to Vietnam War Among American Students,” British Journal of Sociology 24, no. 3 (1973): 294.

[9] The Sandspur, October 20, 1967.

[10] Jack C. Lane, The Sandspur, October 20, 1967.

[11] “Give Peace A Chance,” The Sandspur, October 17, 1969.

[12] “Give Peace A Chance,” The Sandspur, October 17, 1969.

[13] “Minutes, College of Arts & Sciences Faculty Meeting, May 15, 1972,” Rollins Scholarship Online, May 15, 1972, https://scholarship.rollins.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1297&context=as_fac/.

[14] Memo from Fred W. Hicks to Jack Critchfield, April 15, 1972, Folder: Vietnam War, RCA.

[15] John Culverhouse, “Walking Out for Peace,” The Sandspur, April 4, 2003.

[16] The speech quoted was delivered February 12, 2003 and can be accessed here; Mass email from Nicole Elaine Gilpin, March 18, 2003, Box: 40G World War I World War II Irac War Vietnam War Afghanistan, Folder: 40E War- Iraq 2003, RCA;

[17] Mass email from Barbara Carson, March 19, 2003, Box: 40G World War I World War II Irac War Vietnam War Afghanistan, Folder: 40E War- Iraq 2003, RCA.

1 thought on “‘Fiat Pax:’ Peace, War, and Protest at Rollins, 1938–2003”