by Prof. Rachel Walton

As a follow up to the Archives’ previous blog post highlighting the history of race relations at Rollins from the time of its founding to the middle of the twentieth century, this piece picks up at the start of the Civil Rights Movement and examines the experiences of Black students, faculty, and others in the community from the moment of integration to the present day. It is important to acknowledge the range and variety of these experiences and to offer a transparent history of what were undoubtedly challenging times for many members of our campus and city.

Those who have conducted research in the archives know that it is not unusual to encounter disturbing or upsetting realities in the archival record. However, our code of professional ethics as archivists urges us to protect, not prevent, access to such materials.[1] Furthermore, we are called upon to archive the broadest range of experiences possible within the bounds of the documentary record, in order to ensure that a multiplicity of viewpoints can be considered and to provide a mechanism for societal accountability and collective memory.[2] These histories, though sometimes painful, are incredibly meaningful to those who lived them and those who inherit them today. This is one of the many reasons we feel it is critical to share the history of race relations as told by the materials in our small College Archives, and we invite the Rollins community and the public to interact with those artifacts both online and in person.

Integration in the South and at Rollins

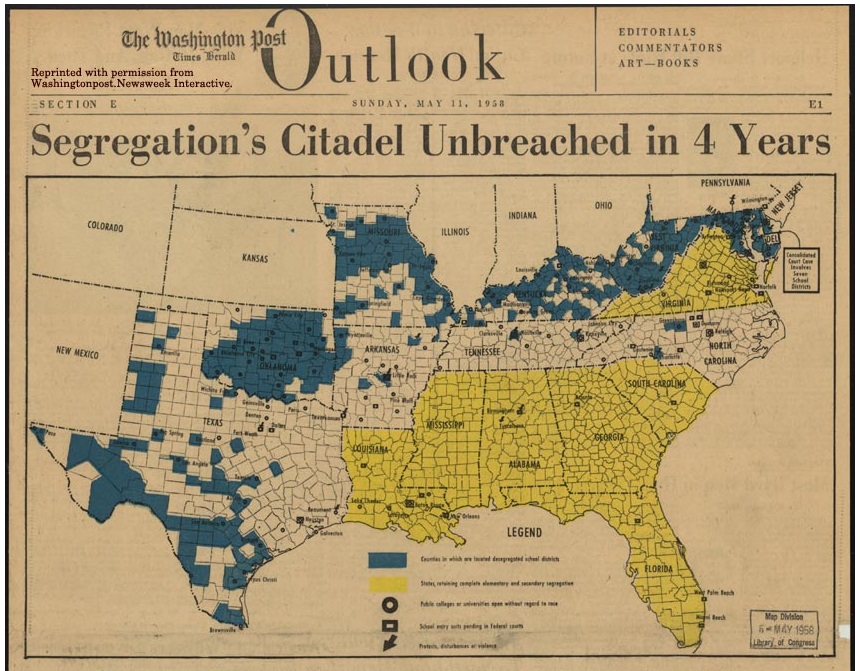

School integration has been a long-fought and hard struggle in the United States. Social justice advocates were working to integrate schools as early as the 1930s. In 1936 the NAACP launched a campaign, led by the Legal Defense and Education Fund (LDF) legal team, to compel the desegregation of southern colleges and universities. Not until 1954, nearly two decades later, would the landmark Supreme Court case Brown v. Board of Education outlaw segregation in schools. However, the vast majority of segregated schools were not integrated until many years later. In 1958, the Washington Post mapped the seven southern states (VA, SC, GA, AL, FL, MI, LA) that continued to maintain segregated school systems, including Florida, labeling them together “Segregation’s Citadel.”[3]

“Segregation’s Citadel Unbreached in 4 Years,” Washington Observer, Sunday, May 11, 1958. Newspaper map. Geography and Map Division, Library of Congress (140). Copyright 1958, Washington Post. https://www.loc.gov/exhibits/brown/brown-aftermath.html#obj140

In 1964, the Civil Rights Act prohibited colleges and universities from discriminating based upon age, sex, race, or religion. Furthermore, to incentivize southern “hold-out” schools, Title VI of The Civil Rights Act stipulated that only institutions with open admissions policies were eligible for federal grant dollars. Beyond the threat of losing federal financial aid, by the 1960s historically white southern colleges like Rollins were starting to feel other major pressures, both internal and external, to start admitting Black students.

For example, outspoken social activist, lawyer, and Rollins economics professor, Royal Wilbur France, was constantly agitating and stirring the pot around race at faculty meetings and in the direct presence of college administrators during his twenty-three years as a faculty member (1929-1952). Known for his history of protest participation and arrests, France was heralded in his obituary as a “crusader for civil liberties.” He eventually left academia, preferring to “devote his time to cases involving the constitutional rights of minority groups” and went on to serve on the executive board of the Emergency Civil Liberties Committee.[4]

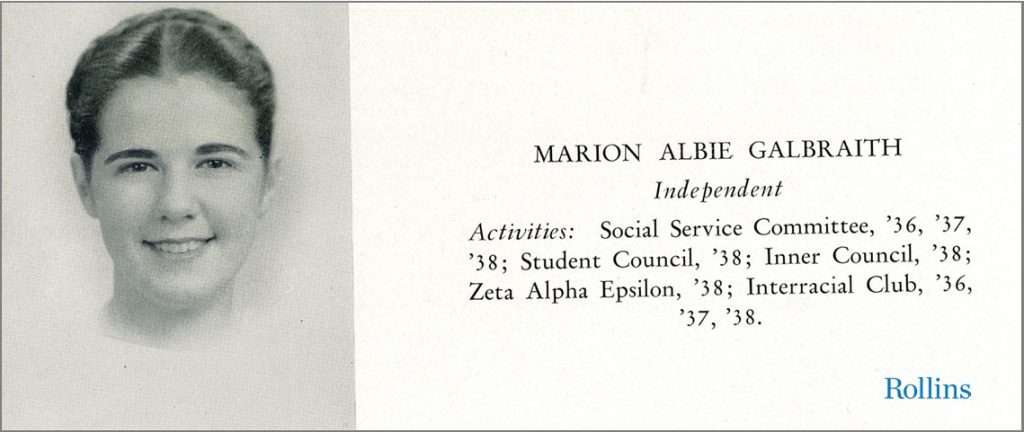

Marion Albie Galbraith ’38, pictured in the 1938 Tomokan yearbook as a senior. Marion Albie Galbraith studied pre-med at Rollins and was an active member of Student Council and the Interracial Club as a student.

In 1964, Rollins alumna Marion Galbraith Merrill tried to apply outside pressure on Rollins administrators and compel them to take the steps needed to integrate Rollins’ student body. In a letter to Dean Alfred “A. J.” Hanna, Ms. Merrill threatened that she was in touch with the Head of the U.S. Commission on Civil Rights and would report on the school’s inaction if matters did not change. Rollins administrators quickly disregarded the claims made by Merrill in their reply, stating that the College’s process of admitting students was not to be discussed and that racial background played no role in the acceptance of an applicant.[5] Despite the evasive response from the higher-ups, Rollins enrolled its first African American student in 1964.

Rollins’ First African American Students

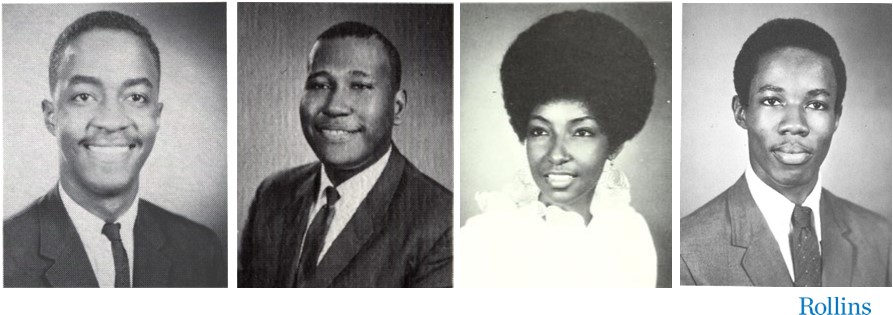

From left to right: Tomokan yearbook photos of John Cox, William Johnson, Lewanzer Lassiter, and Bernard Myers.

In Fall 1964, John Mark Cox Jr. entered Rollins as its first African American student. He was joined the following year by freshman Della Dunn. While John and Della did not complete their degrees at Rollins, they led the way for many others who would follow in their footsteps.[6] Lewanzer Lassiter, Bernard Myers, and William Johnson began as freshmen in 1966, and they were also the first African American graduates of Rollins in 1970. The archival records make it very clear that many of the first Black students at Rollins in the late 1960s and early 1970s were not just acclimating and adjusting, they were leaders and major contributors to co-curricular and other campus spaces.

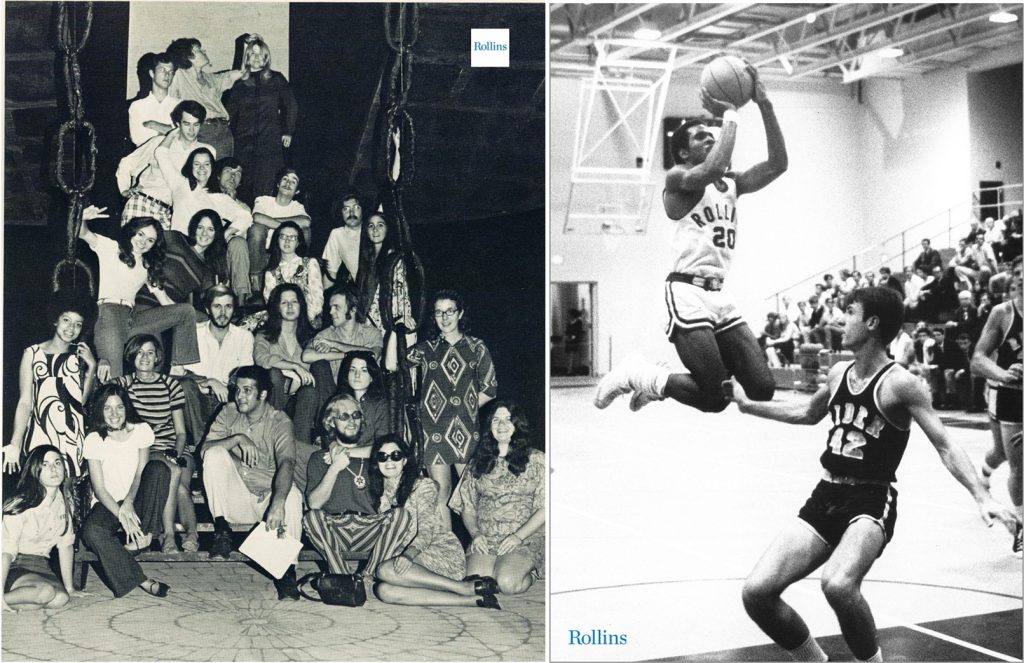

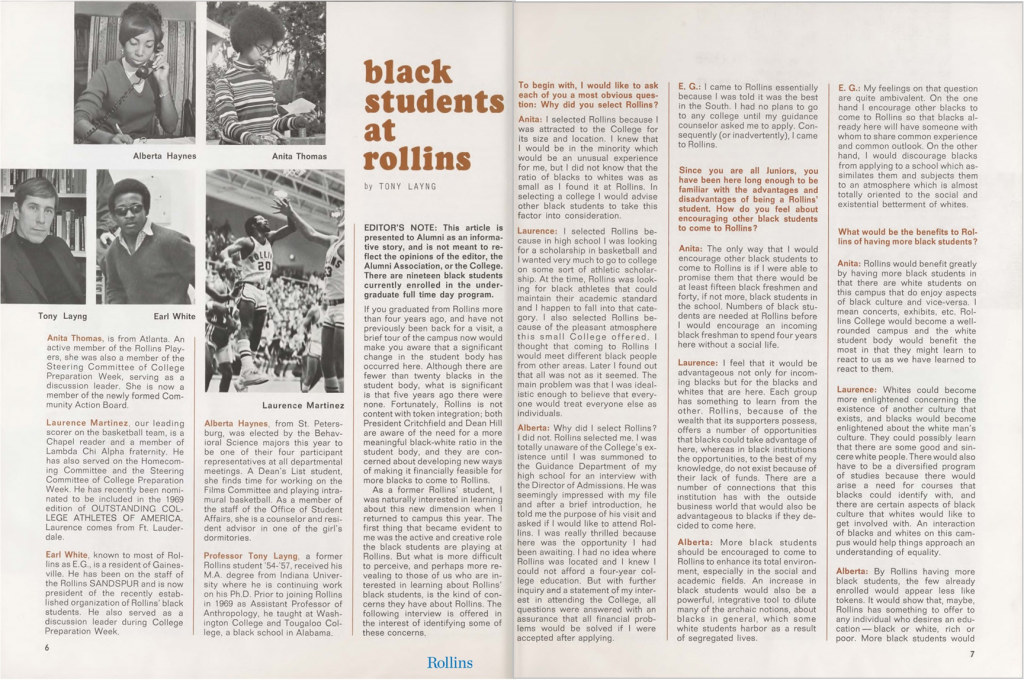

Bernie Myers ‘70 was involved in Rollins’ new soccer program and also served as the student manager for the men’s basketball team. Anita Thomas ‘73 was an active member of the Rollins Players drama group, as well as the campus Community Action Board. Laurence “Larry” Martinez ‘72 was a leading scorer on the men’s basketball team and a member of the Lambda Chi Alpha fraternity. Chuck Morton ’72 was a stand-out two-sport athlete in both basketball and baseball and a frequent performer at student social functions. Reggie Brock ‘73 was a star on the men’s tennis team and an RA for a men’s dorm in his senior year. Likewise, Alberta Haynes ‘71 was an RA for a women’s dorm on campus, as well as an outspoken member of the Office of Student Affairs team. Earl “E. G.” White ‘71 was a writer for the Sandspur student newspaper and a president of the newly formed Black Student Union (BSU), as was Krisita Jackson ’73, who stayed on the Dean’s List while still serving an active role in both the BSU and Student Government.

Anita Thomas ‘73 (pictured far left) with the Rollins Players theater group in the 1971-1972 Tomokan yearbook. In the photo on the right, Laurence “Larry” Martinez ’72 takes a jump shot over his defender. This was Martinez’s sophomore year at Rollins and his second year on the basketball team, 1968-1969.

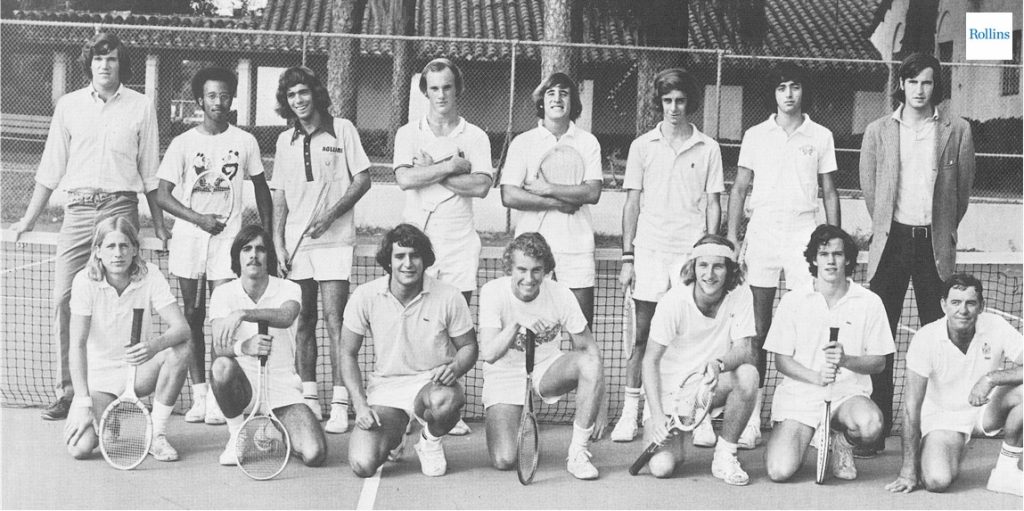

Reggie Brock ’73 (standing, second from the left) pictured with the men’s tennis team, Tomokan yearbook photo, (1973): https://www.jstor.org/stable/community.39301359.

A Petition to the Administration

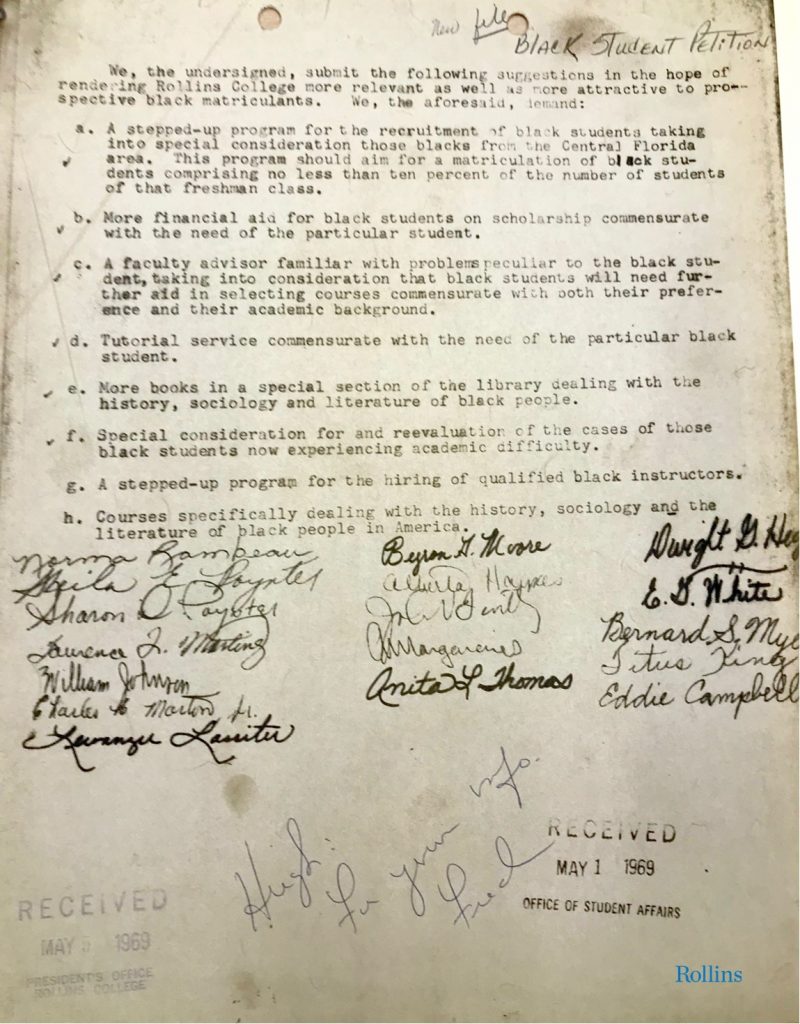

In 1969 seventeen of Rollins’ first Black students boldly signed a petition addressed to Rollins administrators advocating for major structural improvements across both campus and curricula, which they felt, if implemented, would improve the overall Black student experience.[7]

Signed Student Petition to College Administrators, 1969. Signed by (in alpha order): Campbell, Eddie; Hayes, Alberta; Higgs, Dwight G.; Johnson, William; King, Titus; Lassiter, Lawanzer; Margeronis, Stacy; Martinez, Laurence; Meyers, Bernard; Moore, Byron; Morton, Charles; Poynter, Shannon; Poynter, Shiela; Rambeau, Norma; Thomas, Anita; Twitty, John; White, E. G.: https://www.jstor.org/stable/community.38482020

These requests included:

- A stepped-up program for the recruitment of Black students;

- More financial aid for Black students on scholarship;

- A faculty advisor familiar with problems peculiar to Black students;

- Tutorial services commensurate with the needs of Black students;

- More books in the library dealing with the history, sociology, and literature of Black people;

- Special consideration for and re-evaluation of Black students experiencing academic difficulty;

- A program for the hiring of qualified Black instructors;

- Courses specifically dealing with the history, sociology, and literature of Black people.[8]

The archival record shows some attempts by the College to address these issues in the 1970s as well as continued advocacy work by Black students themselves, spearheaded mainly by the vocal and dedicated members of the Rollins BSU. These requests provide a great deal of insight into the early struggles of these first Black students at Rollins and point to their own collective vision for what they hoped Rollins could be for future students of color.

The Early Black Student Experience at Rollins

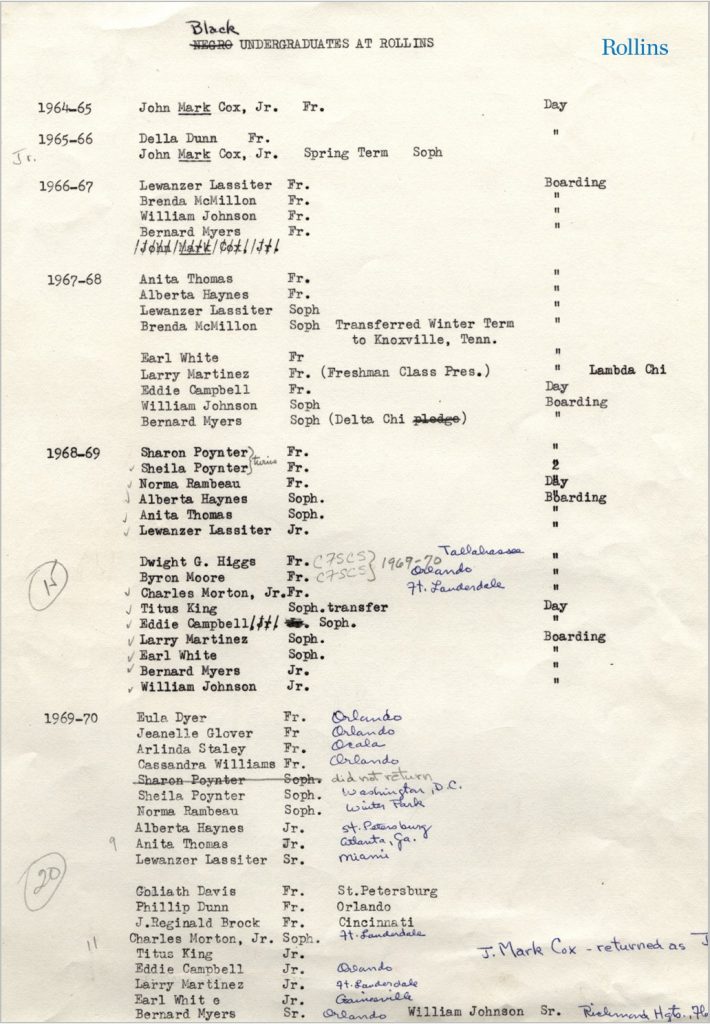

The number of African Americans admitted to Rollins increased steadily through 1970. You can see from the student records document below and in the corresponding chart that there were ten times as many African American students (20) at Rollins in the 1969-1970 academic year compared to the 1965-1966 school year (2).[9] This may have been due to the College’s active recruitment of Black freshmen on both athletic and academic scholarships. Student reflections confirm this in many cases. For example, Laurence Martinez explained his choice to be at Rollins thusly: “Rollins was looking for Black athletes that could maintain their academic standard and I happen to fall into that category.”[10] Alberta Haynes also revealed that she didn’t choose Rollins, but rather Rollins chose her: “I was totally unaware of the College’s existence until I was summoned to the Guidance Department of my high school for an interview with the Director of Admissions. He was impressed with my file… and of course I was thrilled because this was the opportunity I had been awaiting.”[11]

| Academic Year | # of Enrolled African American Students |

| 1964-1965 | 1 |

| 1965-1966 | 2 |

| 1966-1967 | 4 |

| 1967-1968 | 9 |

| 1968-1969 | 15 |

| 1969-1970 | 20 |

“Black Undergraduates at Rollins,” registration document, 1970: https://www.jstor.org/stable/community.38481960. A list (and corresponding chart showing the number) of Black students attending Rollins between the academic year 1964-1965 and 1969-1970.

However, we should not draw a straight line between an improvement in the number of Black students at Rollins and the quality of their overall college experience. These students dealt with a continuation of underlying racist attitudes that had been a part of Rollins and the larger community of Winter Park for many decades. As trailblazers they were quite aware of their impact on campus life as well as the legacy they left for future generations. Perhaps this is why they were not silent about their experiences, both positive and negative. These students participated in interviews, contributed to a special issue of the Sandspur student newspaper, organized and chartered the BSU, and established the annual tradition of Black Awareness Week at Rollins.

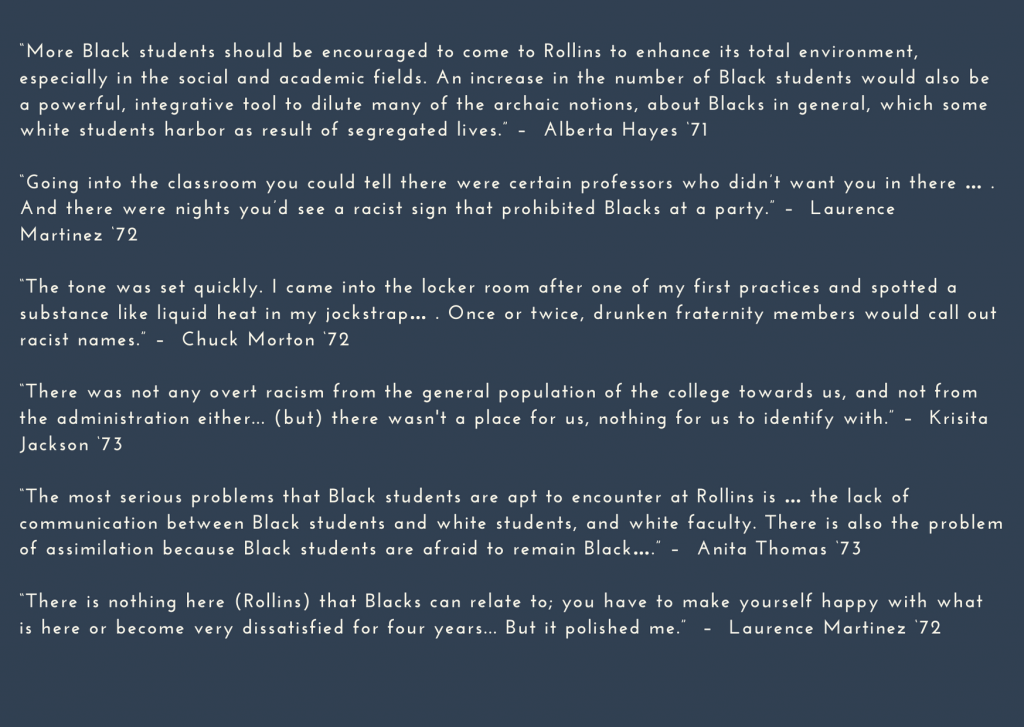

In 1970, Professor Tony Layng, a former student and then a Rollins anthropology professor, interviewed several of the college’s first African American students for a write-up in the Rollins College Alumni Record. Layng did not shy away from the tough issues. He asked questions like “What do you consider to be the most serious problems that Black students encounter at Rollins?” and “How do you feel about encouraging other Black students to come to Rollins?”[12] In addition, during recent years, students and faculty at Rollins have also conducted similar oral history interviews about what life was like for these first early students at Rollins. Below are some quotes from these various interviews.[13]

Prof. Layng’s article, “Black Students at Rollins,” was published in the February 1970 issue of The Rollins College Alumni Record. See https://www.jstor.org/stable/community.38481960.

Taken together these reflections show that their experiences were not all the same. They saw and experienced a variety of different challenges including harassment, isolation, assimilation, general dissatisfaction, and even the obstacle of trying to educate white students about Black life and culture. Some, like Laurence Martinez, would not set foot on campus again for decades due to the trauma he experienced (and yet he recognized that the experiences “polished him” as a person). Others like Krisita Jackson would be active advocates of the college throughout their life, viewing the four years of time at Rollins as productive and enjoyable.

The Black Student Union

Many of the students interviewed by Layng found community in the Rollins Black Student Union (BSU). While it was officially chartered in the Spring of 1972, the BSU was active as an unofficial group years before that; in fact, the organization’s Constitution and Bylaws were drawn up in the 1970-1971 school year. The group first appeared photographed for the Tomokan yearbook in 1973, with its members posed on the front steps of the Knowles Memorial Chapel.

Rollins Black Student Union, Tomokan Yearbook (1972-1973): https://www.jstor.org/stable/community.39301363. President Krisita Jackson ‘73 is standing on the far left of the photo at the bottom of the stairs.

The first elected BSU President was junior, economics major Krisita Jackson ‘73. The group met in regularly scheduled meetings in the Alumni House and had a total of 20 members in its first official year.

BSU established four primary goals at the time of its charter:

- Create a relevant social and academic atmosphere for Black students;

- Foster a unity between Black students on campus and the surrounding community;

- Provide Black students with positive symbols and values that are essential to the development of the whole individual;

- Plan programs and activities emphasizing the cultural achievement of Black people.[14]

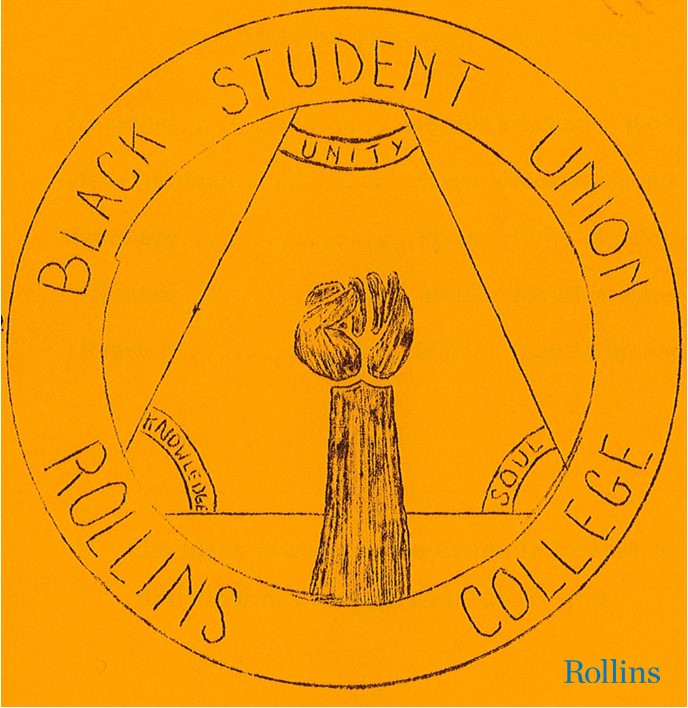

Archival records show that BSU members were not only passionate advocates of equality on campus, they were also deeply aware of the national social and political landscape surrounding racial justice. In fact, the raised fist symbol of the Black Power movement was the organization’s first adopted logo, appearing on the BSU’s first members directory in 1972.

Front cover of the Black Student Union Directory, 1972. Box: 12, Black Student Union. Student Organizations and Histories. Rollins College Archives & Special Collections, Winter Park, FL.

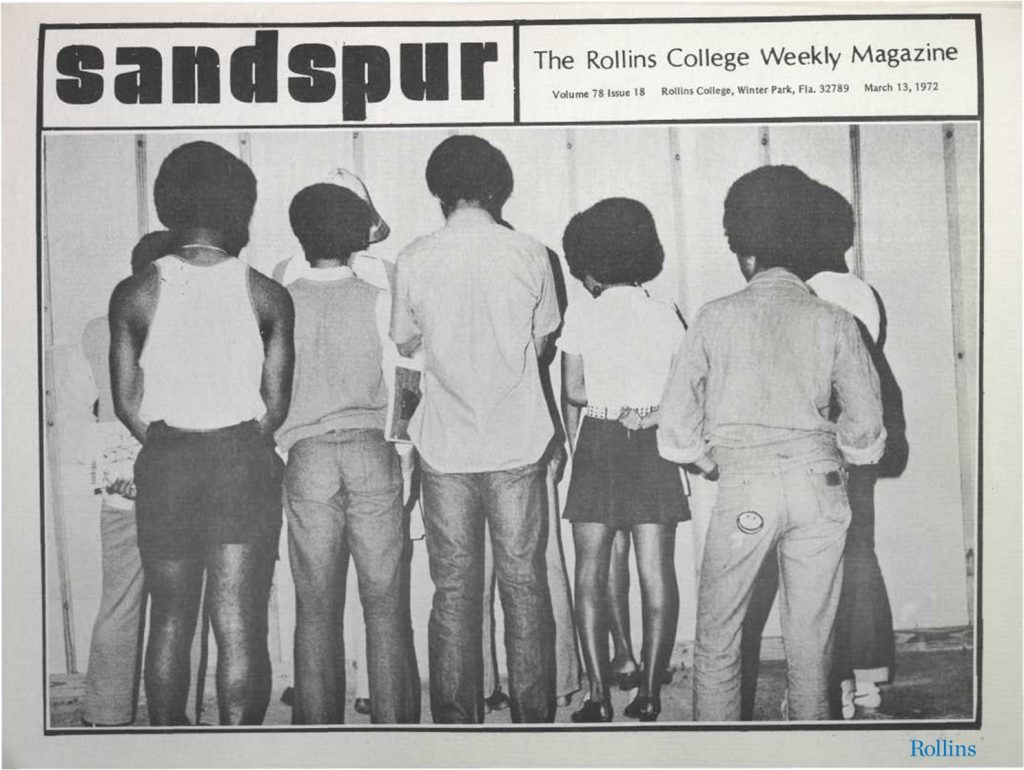

True to its established goals, the BSU immediately began active outreach and advocacy work, quickly becoming a visible student group on campus. The March issue of the 1972 Sandspur was devoted almost entirely to the voices of BSU members. Editors were very intentional about this choice, explaining the issue’s theme and intent on its final page:

The intention was to give the BSU members an opportunity to speak out about the problems they see…. Many times, the problems and dilemmas Black students realize are overlooked by the white members of this community. Some call it racism, some call it unawareness, and some call it ignorance. Perhaps, what the Black students say here [within this issue], can help us to overcome these inadequacies…. No matter what the response – good or bad – at least an affirmative step has been taken… .[15]

Rollins College Sandspur, Vol. 78, No.18, March 13, 1972 (cover page): https://stars.library.ucf.edu/cfm-sandspur/1418/.

Within this unprecedented issue, Cassandra Williams ’73 wrote about the aims of a recent campus demonstration at the student union involving Black students.[16] Jeanelle Glover ‘73 elaborated about the challenge of “Pseudo-Liberalism” at and beyond Rollins.[17] Theotis Bronson ‘73, Byron Moore ‘72, and Chuck Morton ‘72 tackled a variety of political issues emerging from the Civil Rights Movement, including but not limited to, busing as a part of (un)equal educational experiences for Black students.[18] Goliath Davis ‘73 wrote about the role of Black teachers and students in higher education settings, and Theda James ‘74 wrote about the place of Black Studies as an academic discipline in college classrooms.[19] Krisita Jackson ‘73 offered a book review of two texts that she believed could help white students better interact with and relate to their Black peers.[20] Finally, Dwight Higgs ’73 offered a creative, personal piece about his own experience of marginalization likening himself to “a bottle of frustration.”[21]

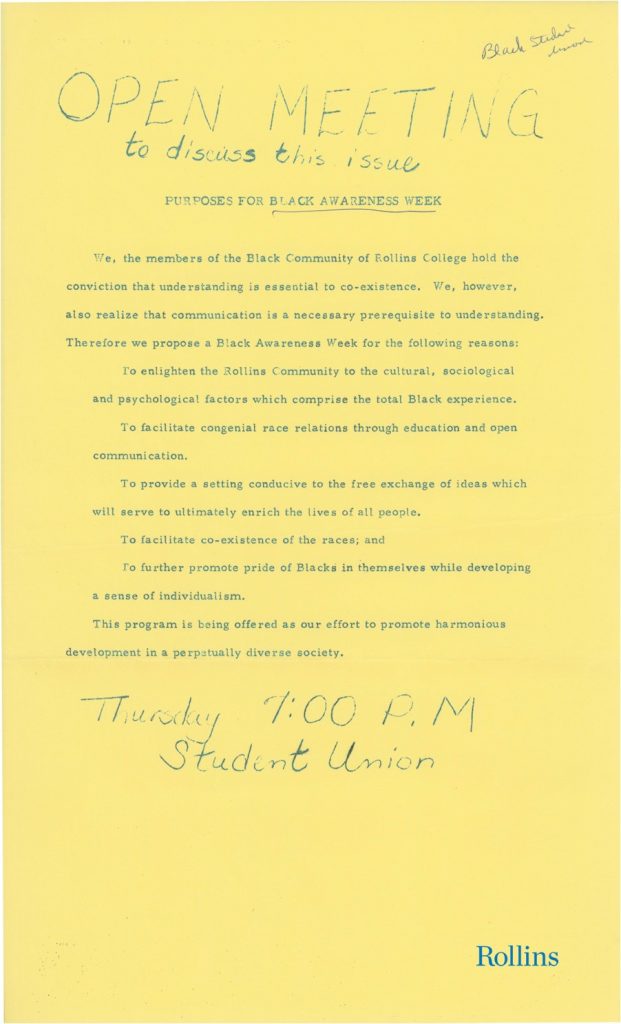

Going beyond just words, the BSU was devoted to public campus programming. It hosted its first Black Awareness Week in February of 1973. The event was intended to foster harmony and diversity amongst the study body, and more specifically to accomplish the following aims:

- to enlighten the Rollins community;

- to facilitate congenial race relations;

- to provide a setting conducive to the free exchange of ideas;

- to facilitate coexistence of the races; and

- to promote pride of Blacks in themselves while developing a sense of individualism.[22]

“Purposes for Black Awareness Week.” Black Student Union Flyer for Open Meeting, 1972: https://www.jstor.org/stable/community.39301371. The flyer invites the Rollins community to attend an open discussion meeting about the reasons for Black Awareness Week planned programming.

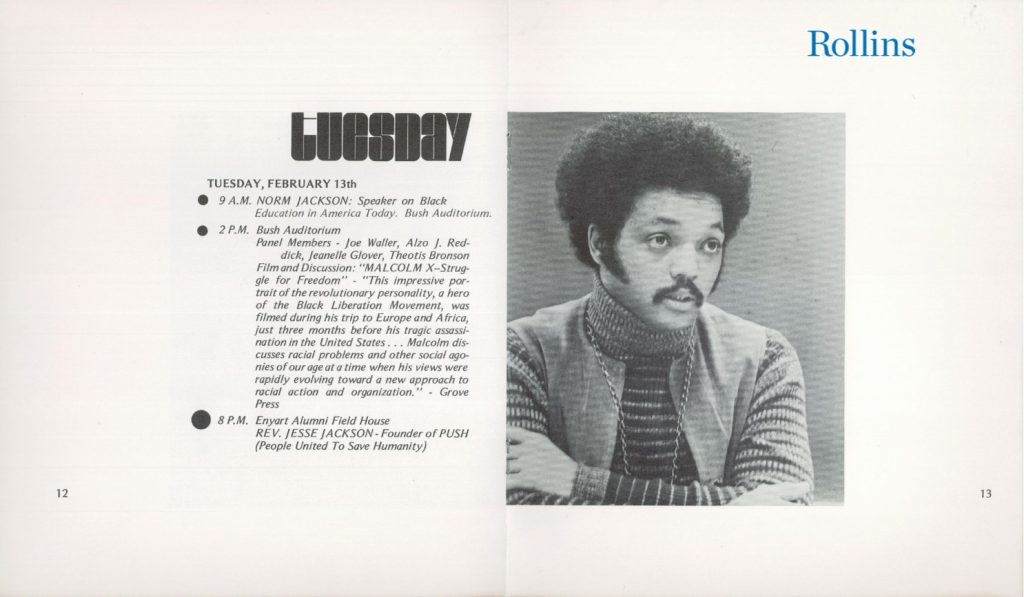

It seems the BSU had substantial support from the College administration for this event, in terms of financial and other planning resources. Records show that the college allocated $2,500 to the BSU for the funding of related Black Awareness Week expenses. In a more recent interview, BSU president Krisita Jackson stressed the fact that this was a truly huge sum the College ended up contributing to the inaugural event’s programing.[23] The 1973 Black Awareness Week included presentations from noted Black leaders such as Reverend Jesse Jackson, artistic demonstrations in various creative forms, and public talks dedicated to fostering an open conversation about race in America.[24] While the event was initially met with a mixed reception by the white student population, it was crucial in laying the foundations by which the BSU and the event itself could grow over time. Following the first Black Awareness Celebration, numerous other events were held annually by the BSU, and Black Awareness Week remained an ongoing program throughout the seventies and eighties at Rollins.

“Tuesday, February 13th (Events).” Black Awareness Week Program. February 12-17, 1973 (pages 12 and 13): https://archives.rollins.edu/digital/collection/diversity/id/82/rec/9. Box: 12, Black Student Union. Student Organizations and Histories. Rollins College Archives & Special Collections, Winter Park, FL.

Early Black Faculty and Administrators at Rollins

Part of the call to administrators in the 1969 student petition was a request for the hiring of qualified Black instructors. In addition, students hoped for more books and courses dealing with the history and literature of Black people and access to an advisor who was familiar with problems peculiar to Black students. Accordingly, the college made a major effort in future years as it moved to better support its Black students.

Professor Eleanor Mitchell Thomas, pictured in the Rollins College Sandspur, Vol. 78, No. 4, October 25, 1971 (page 5): https://stars.library.ucf.edu/cfm-sandspur/1404/.

Eleanor Mitchell Thomas, hired in 1971, was the first Black faculty member at Rollins. She was an Orlando native with an advanced degree from Johns Hopkins University who came to Rollins by way of Prairie View A&M College in Texas. Eleanor taught political science courses with a strong international focus – International Relations, Developing Nations, and Comparative Government – and in a 1971 interview with The Sandspur, she explained that the main objective in all her courses was to “break down the stereotypes and preconceived notions we have in the country about the rest of the world.”[25] Mitchell also led a study abroad course to Africa in the Summer of 1972, traveling with students through Senegal, Liberia, Ivory Coast, Ghana, and Nigeria. This unique curriculum was intended to infuse diversity into the curriculum. After two years of teaching at Rollins, Mitchell would move on to launch a highly successful legal career, becoming the first Black woman to hold the position of Assistant General Counsel in Florida’s Supreme Court.

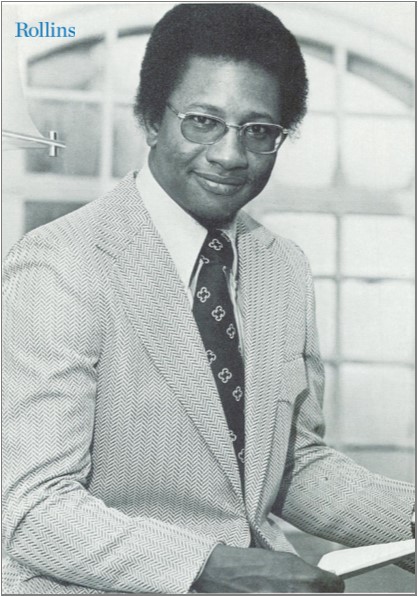

Alzo Reddick, pictured in the 1974 Tomokan yearbook (Photo: Rollins College Archives)

Alzo J. Reddick was the first Black administrator at Rollins College, hired, like Eleanor, in 1971. He was also a local, graduating from Orlando’s own Jones High School. After attending Paul Quinn College in Waco, Texas, on a football scholarship, he spent two years in the Army before becoming a high school teacher in Winter Park. In fact, Reddick was the first Black male to teach at Winter Park High School, just down the street from Rollins. Reddick transitioned into the role of Assistant Dean of Student Affairs during a critical time in the college’s history, and along with that role came a litany of other duties — traveling and interviewing for the admissions office, teaching as an adjunct professor in the History Department teaching African American History topics classes, and serving as a “problem solver” for students with scholastic and other co-curricular issues. In particular, Reddick was essential in the mentoring and supporting of Rollins’ first cohorts of Black students, who faced unusual and overwhelming challenges at a majority white college.[26] In an interview with The Sandspur, Reddick explained that most Black students felt an intense “isolation,” so his goal in taking on this unique role was to “help bring about more interaction between Black and white students for their mutual benefit. Both groups offer great opportunities for the other to learn about different cultural backgrounds and lifestyles….” [27] Reddick was also very involved with the Black Student Union and its annual programming; he served on the Black Awareness Week planning committee and presented guest speaker at events.

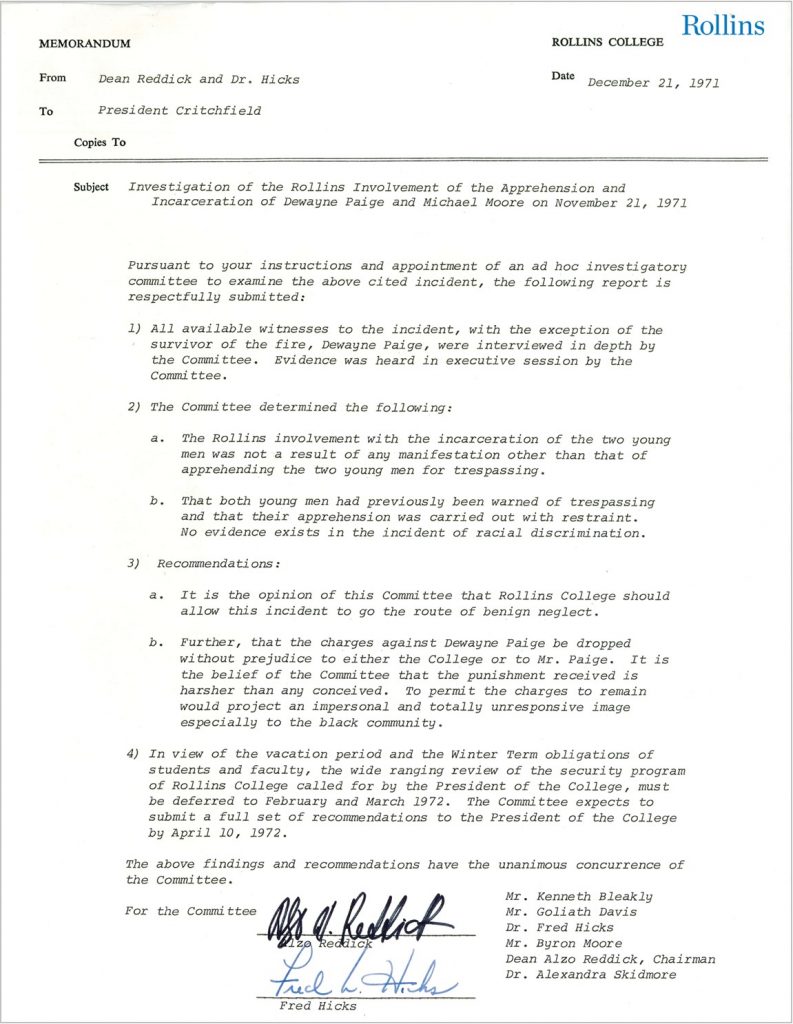

Steadily, Reddick would move up in the ranks at Rollins over the course of more than ten years. However, in his first year as an administrator he took on an especially difficult task – Reddick was called upon to lead an internal investigation of the college after a routine campus arrest turned into a tragedy. On the evening of November 21, 1971, two young Black men were arrested on the Rollins campus after reports of a robbery at Pugsley Hall. Dewayne Paige and Michael Moore of Winter Park were accused of loitering on the campus, and were (wrongly) suspected of being the perpetrators of recent break-ins. After being questioned by Campus Security, the two men were arrested and taken to the Winter Park Jail on charges of trespassing. The following day, a fire broke out in the inmate cell block of the jail, which resulted in the tragic death of Michael Moore. Reddick led a committee of faculty, staff, and students comprised of both white and Black individuals, and launched a full investigation in the aftermath of the fire. The Committee reported to administrators their unanimous findings that December – their inquiries confirmed that the arrest of the two men was simply the apprehension of two trespassers, who had been previously warned to remain off campus, and that the College should opt for the route of “benign neglect” over addressing any concerns of racial targeting. Dewayne Page was not interviewed at that time, but the Committee suggested that all charges against him be dropped, and they eventually were.

“Investigation of the Rollins Involvement of the Apprehension and Incarceration of Dewayne Paige and Michael Moore on November 21, 1971.” Memorandum from Dean Reddick and Dr. Fred Hicks to President Jack Critchfield on December 21, 1971. Rollins College, Winter Park, FL.

In the 1970s, Reddick served as Minority Affairs Coordinator, Director of Minority Affairs, and then Affirmative Action and Equal Opportunity Officer at Rollins. The College then appointed him Director of Affirmative Action and Diversity Programs in 1979. Reddick would later move on to become Orange County’s first Black Representative, the first Black legislator elected to the legislature to ever pass two constitutional amendments, and would hold elected office in the Florida House of Representative for eighteen consecutive years (1982-2000). Coming from Winter Park High School, where he says he experienced a lot of discrimination and inequity, Reddick describes his time at Rollins as “most productive,” and says he felt well respected by the rest of the faculty. He remains a local fixture in higher education, especially at nearby UCF, where he led the Soldiers to Scholars program.[28]

Continued Campuswide Efforts for Diversity and Inclusion

Recent decades have shown the college’s continued commitment to solving some the diversity and inclusivity problems pointed out by Rollins’ first Black students in 1969. Leaders on campus (faculty, staff, students, administrators) have made ongoing efforts to infuse academics, campus programming, and the general college environment with racially diverse subject matter, particularly for topics surrounding Black history and culture.

The Africa and African American Studies (AAAS) Program was created in 1986, when members of the Anthropology and Modern Language departments pushed to create an academic minor focusing on the impact of Africa and African-American culture on the western experience. AAAS is still an active program on campus today, offering a highly interdisciplinary model for student learning about Black Studies topics. Even more recently, in 2014, the Center for Inclusion and Campus Involvement was established at Rollins, through the merger of the Office of Multicultural Affairs (OMA) and the Office of Student Involvement and Leadership (OSIL), to foster further awareness, advocacy, and community for Rollins’ increasingly diverse student body.

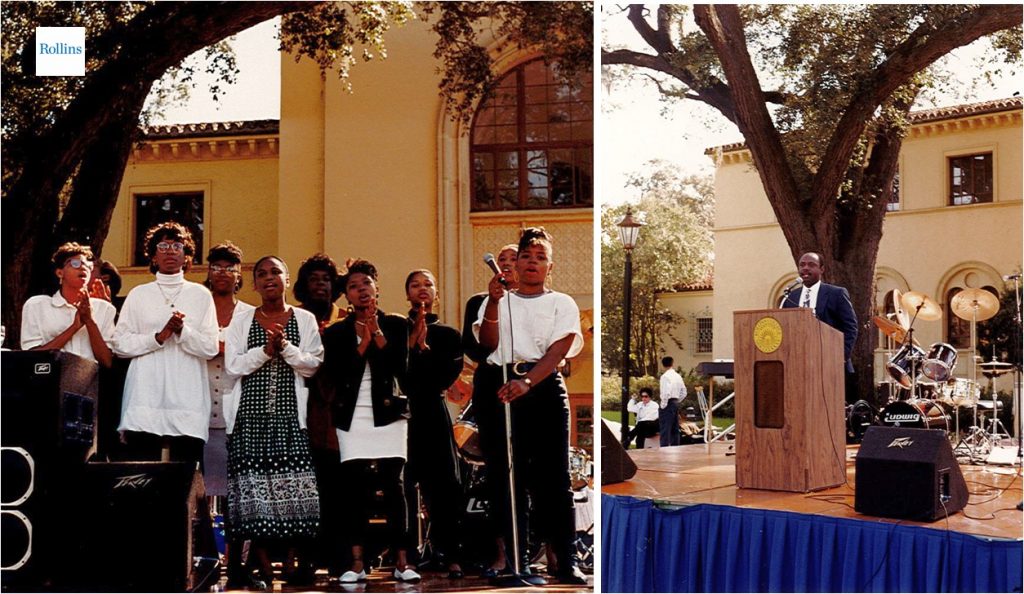

Rollins has a history of participating in several kinds of Black history and culture celebration programming over the years. The long-lived and popular Black Awareness Week of the 1970s and 1980s transitioned to a new model in the Spring of 1991 for a multi-day event called Africana Fest, which would run for several years in the 1990s. The program was intended to emphasize African cultural celebrations and honor Black heritage through a series of performances, events, and talks on campus. Again, Anthropology faculty were very involved in this work, particularly Anthropology Professor Deidre Crumbley, as was the Black Student Union. As the coordinator of Africa and African American Studies at Rollins College, Crumbley described the aims of 1991 event as “an experience which immerses participants in the music, dance, drama, cuisine, visual arts, crafts, literature, and religious experiences of people of African descent.”[29]

Student performers and a speaker at the first Africana Fest, 1991. Both photos can be located at: Folder 28, “Africana Fest,” Cabinet 1, Drawer 1, Photographical Collection, Rollins College Archives & Special Collections, Winter Park, FL.

In the eighties, Rollins was the only school in the Orlando area to formally celebrate Martin Luther King Jr. Day as an official holiday. Since 1990 the College has been deeply involved with the highly popular and well attended Zora! Festival, in collaboration with the nearby Association to Preserve the Eatonville Community, Inc. (P.E.C.). The Zora Festival is a multi-day, community arts and humanities event hosted in Eatonville, Florida. Traditionally, some type of festival event programming is held on Rollins’ campus and/or involves collaboration with Rollins faculty, staff, and/or students. In 2021, Rollins President Grant Cornwell co-hosted a conversation with author Isabel Wilkerson about critical race theory.

The 29th Annual Zora Neale Hurston Festival of the Arts and Humanities (2018), The Communities Conference Program, Entrance, Rollins College, Winter Park, FL: https://scholarship.rollins.edu/communities_conference/3/.

Furthermore, the campus community has also chosen to honor outstanding Black individuals, living and past, in its somewhat unusual campus memorial structure – the Walk of Fame. Most Rollins students encounter the Walk of Fame, a stone-lined walkway encircling the central lawn space at the heart of campus, on a daily basis. However, few know whose names are enshrined in these rocks. The Walk of Fame was the brainchild of former Rollins President Hamilton Holt ‘49H.[30] Created in 1929 from a set of twenty stones, the current Walk of Fame consists of more than 500 stones. However, until the 1980s, only one of those stones honored the life of a famous African American figure; Booker T. Washington was added to the collection of stones sometime in the 1930s. Most of the stones currently in the Walk of Fame honoring African American individuals were added after 1980 (see the list below).

| Year the Stone was Added | Name(s) of Honoree(s) |

| 1983 | Martin Luther King Jr. |

| 1985 | Mary McLeod Bethune |

| 1987 | Zora Neale Hurston |

| 1994 | Maya Angelou |

| 1997 | Danny Glover and Felix Justice |

| 2014 | Jackie Robinson |

On January 23, 2014, Rollins baseball players attended the stone-laying ceremony for legendary baseball player Jackie Robinson: https://360.rollins.edu/arts-and-culture/jackie-robinsons-values-in-sports-and-life (Photograph by Scott Cook)

More recently, there seemed to be an effort to ensure better diversity and representation in the selection of Walk of Fame honorees. We’re still talking about who belongs in the Walk of Fame and, for that matter, in other public memorials to our past. Last year, in response to and in support of the #BlackLivesMatter movement, Rollins officially began a campuswide Anti-Racism initiative. As a part of that work, Rollins President Grant Cornwell formally removed nine stones commemorating advocates of slavery and officers of the Confederate Army from the Walk of Fame. In his September announcement to campus, he elaborated: “Doubtless there may be other stones commemorating persons who would not stand up to critical scrutiny were we to use our mission as a lens, but that is not what we are doing now… I am not averse to further considerations, but at this moment we take this action as a symbol of both protest and reconciliation.”[31] The campus conversation about this decision and its motives continued into the Fall of 2020. In November, a virtual open forum panel of academics, citizens, and curators discussed many issues surrounding “Confederate Monuments in the 21st Century,” giving space and voice for the Rollins and Winter Park community to grapple with the tough issues left behind by racist southern legacies.

Conclusion and Future Work

The evolution of race relations at Rollins was, and continues to be, a close reflection of the larger societal changes and social progress we experience in the United States as a nation. Rollins’ journey to integration, and its continued roadmap to diversity and inclusion has been and will be, a long and winding path, neither a straight line nor a foregone conclusion by any means. Over the last one hundred and thirty-six years, brave and forward-thinking leaders at Rollins – students, faculty, staff, administrators, and other advocates – have worked tirelessly and with great conviction to build a diverse and cherished community of learners and create a campus characterized by integrity, respect, and understanding.

Today, Rollins is a much richer experience for minority students. Approximately 6.31% of Rollins’ students are Black or African American, and more than 44% of the student body identify as races other than white.[32] In an interview with the Sandspur in 2018, Ashley Williams ‘18 acknowledged the improvement in campus diversity during her four years as a student. “Diversity and inclusion has increased tremendously during my years at Rollins. It has been such a pleasure to meet and interact with people from all walks of life. However, there is still work that needs to be done … .”[33] The flurry of support and activism on behalf of Black people in America during the Summer of 2020 indicates that Williams was right, further progress is still needed. In a September 2020 article for The Sandspur, current Black Student Union President Papaa Kodzi explained that, while much has been achieved through the #BlackLivesMatter cause nationally, Rollins’ efforts must continue with even deeper resolve in the future, if we are to secure further meaningful improvements for people of color on our campus, and in fact these values must become part of our identity as a College:

This summer we saw racism surface in dramatic ways, and we saw activism rise up in new and powerful ways as well…. One thing became abundantly clear [is that] … in some way, shape, or form, everyone has the capacity to advocate for justice…. [And] it is easy to get exhausted, [but this] … is more than a moment. It is more than a movement. It must become a lifestyle…. Let this awareness affect your heart. Let that new heart affect your actions. Let those actions develop into a lifestyle dedicated to making this world better for those it has been cruel to….[34]

Kodzi’s words, like those of the first Black students at Rollins who signed the 1969 petition to college administrators, are history in the making. They offer both a challenge to our majority white campus community for continued change and advocacy and, in some ways, also provide the roadmap for achieving a truly inclusive Rollins in the future.

The Archivists would like to end this two-part blog post with a note of appreciation.

First, thank you to the Anti-Racism Learning Group for asking us to present about this topic. It is an honor to be a part of this ongoing campus conversation. We also need to thank our wonderful Archival Specialist, Darla Moore, an absolutely invaluable member of our Archives team. Darla was critical to the research, writing, and posting of these two blog pieces as well as many of the artifacts linked to throughout. In addition, we need to thank the Olin Library for supporting our work as well as the Associated Colleges of the South, which provided grant funding for research on this topic. Finally, and most critically, we need to thank all people who have added to our understanding of this important history. The researchers who brought this information to life are our faculty and student researchers in the Rollins History department: Dr. Julian Chambliss and his Digital History classes, Dr. Brandon Jett and his Public History students, and Dr. Claire Strom with dedicated student researchers in all her immersive archives classes over the last three years.

[1] Society of American Archivists. “Core Values Statement and Code of Ethics.” https://www2.archivists.org/statements/saa-core-values-statement-and-code-of-ethics

[2] Ibid.

[3] “Segregation’s Citadel Unbreached in 4 Years,” Washington Observer, Sunday, May 11, 1958. Newspaper map. Geography and Map Division, Library of Congress (140). Copyright 1958, Washington Post. https://www.loc.gov/exhibits/brown/brown-aftermath.html#obj140

[4] “Dr. Royal Wilbur France Dies; Crusader for Civil Liberties, 78,” New York Times, July 11, 1962.

[5] Letter from President Hugh McKean to Mrs. Horace S. Merrill, February 1, 1965. Box, 139, Folder 24, Merrill, Marion Galbraith. Alumni Files. Rollins College Archives & Special Collections. Winter Park, FL.

[6] Della was only recorded attending Rollins for the 1965-1966 school year. John Cox left in the Spring of 1966, returned in Fall of 1969, and left the College again that same year.

[7] Signed Student Petition to College Administrators, 1969. Box 5, African American Students, Folder 7, Student Petition, 1969. Student Organizations and Histories, Rollins Clubs and Cultural Organizations. Rollins College Archives & Special Collections, Winter Park, FL. https://www.jstor.org/stable/community.38482020

[8] Ibid.

[9] Black Undergraduates at Rollins, 1964-1970. Box 5, African American Students, Folder 7, Student Recruitment 1970s. Student Organizations and Histories, Rollins Clubs and Cultural Organizations. Rollins College Archives & Special Collections, Winter Park, FL. https://www.jstor.org/stable/community.38481960.

[10] Tony Layng, “Black Students at Rollins,” Interview, Alumni Magazine, February 1970 (page 7): https://www.jstor.org/stable/community.38481960.

[11] Ibid.

[12] Ibid, pages 6-8.

[13] Ibid.

[14] Constitution of the Black Student Union of Rollins College, Article I, Section II, 1970-1971. Box: 12, Black Student Union, Folder, BSU 1970-1971. Student Organizations and Histories. Rollins College Archives & Special Collections, Winter Park, FL. https://www.jstor.org/stable/community.39301370

[15] Rollins College, Sandspur, Vol. 78, No. 18, March 13, 1972 (page 20): https://stars.library.ucf.edu/cfm-sandspur/1418/.

[16] Ibid, page 2.

[17] Ibid, page 3

[18] Ibid, pages 3, 4, and 16.

[19] Ibid, pages 8 and 9.

[20] Ibid, page 11.

[21] Ibid, page 16.

[22] “Purposes for Black Awareness Week.” Black Student Union Flyer for Open Meeting, 1972. Box: 12, Black Student Union. Student Organizations and Histories. Rollins College Archives & Special Collections, Winter Park, FL. https://www.jstor.org/stable/community.39301371.

[23] Memo to the Faculty from Krisita Jackson, November 30, 1972. Box: 12, Black Student Union. Student Organizations and Histories. Rollins College Archives & Special Collections, Winter Park, FL. https://www.jstor.org/stable/community.39301365

[24] Black Awareness Week Program, February 1973. Box: 12, Black Student Union. Student Organizations and Histories. Rollins College Archives & Special Collections, Winter Park, FL. https://archives.rollins.edu/digital/collection/diversity/id/82/rec/9

[25] Rollins College, Sandspur, Vol. 78, No. 4, October 25, 1971 (page 5): https://stars.library.ucf.edu/cfm-sandspur/1404/.

[26] Ibid, page 12.

[27] Ibid.

[28] More information about Alzo Reddick and the Soldiers to Scholars Program is available here – http://orlandomemory.info/people/dr-alzo-jackson-reddick-oral-history-interview/.

[29] Deidre Crumbley, April 19, 1990 (announcement). “AfricanaFest 1991: The First Annual Festival of Africana Culture.” Archives and Special Collections, Olin Library, Rollins College, Winter Park, Florida.

[30] More information about The Walk of Fame can be found at: https://lib.rollins.edu/olin/Archives/Architecture/Arch/Walk_of_Fame.htm.

[31] Senal Hewage, “President Cornwell Removes Nine Stones from Walk of Fame,” Sandspur, September 24, 2020: http://www.thesandspur.org/president-cornwell-removes-nine-stones-from-walk-of-fame/.

[32] “Student Racial/Ethnic Profile (All Academic Units),” Rollins College Fact Brochure, Office of Institutional Research (page 2): https://www.rollins.edu/ir/facts-figures/fact-book.html.

[33] M. Leaden, “Discrimination to Diversity: The History of Black Students at Rollins,” Sandspur, February 1, 2018: http://www.thesandspur.org/discrimination-diversity-history-Black-students-rollins/.

[34] Papaa A. Kodzi, “BSU President Reflects on Summer of Anti-racist Activism,” Sandspur, September 24, 2020: http://www.thesandspur.org/bsu-president-reflects-on-summer-of-anti-racist-activism-2/.

1 thought on “Pathway to Diversity – The History of Race Relations at Rollins: A Brief Overview from the Archives, Part Two (1951-Present)”