by Prof. Wenxian Zhang

Being one of the oldest institutions of higher learning in Florida, Rollins’ journey to diversity and integration is long and winding. The history of race relations at Rollins is a close reflection of broad societal shifts in the United States, as major national trends in social progress have profoundly shaped the growth of the college since its founding in the late nineteenth century. Through examining primary documents held in the College Archives, we hope to provide an overview on the progress of race relations at Rollins before, during, and after integration. Our goal is to not only recognize those trailblazers and brave leaders—students, alumni, faculty, staff, administrators, and social advocates—for their roles and contributions over the past 136 years, but also provide an opportunity for our academic community to engage in continual, open discussions about race, diversity, and inclusion at Rollins.

The Founding of Rollins College and Its Early Years

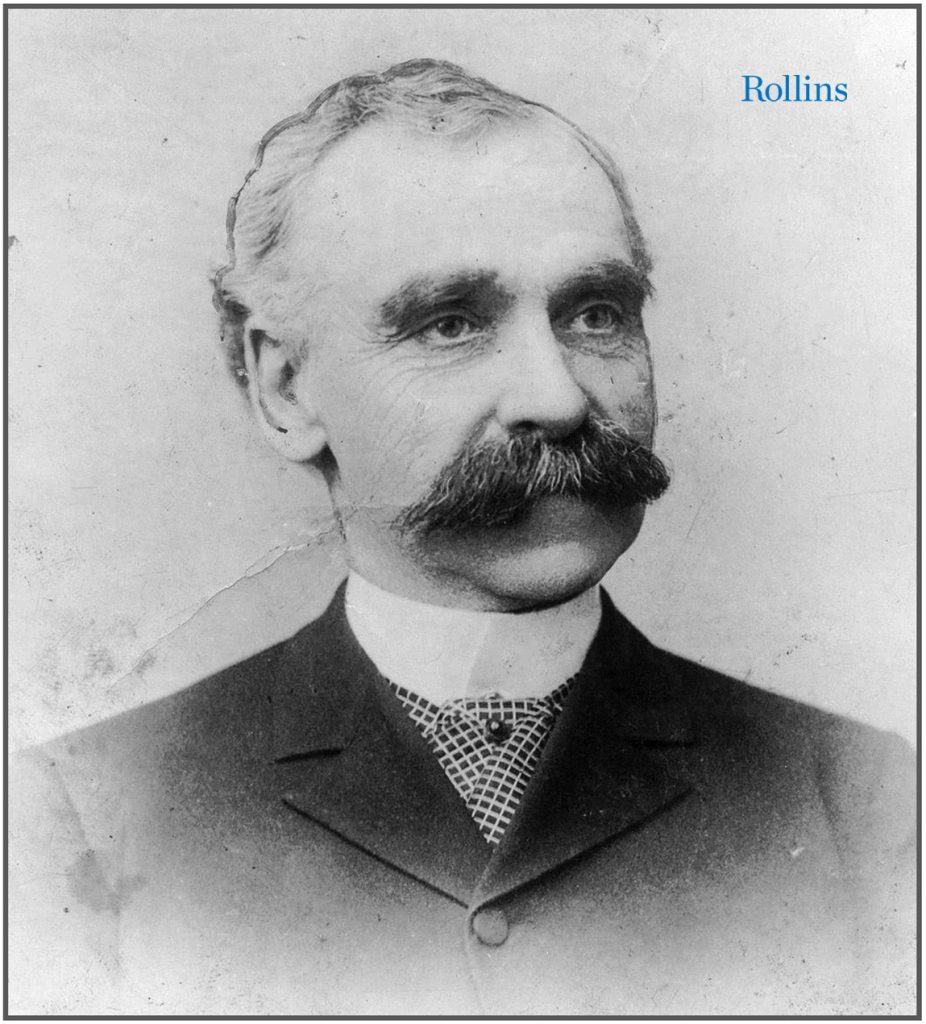

Pioneers began to settle in Central Florida around the mid nineteenth century. Originally named Lakeview in 1858, present-day Winter Park was once called Osceola, since it was believed that the area was once the camping ground of the Native American Chief of the Seminole tribe. The birth of Winter Park is linked to the construction of the South Florida Railroad. When Loring Chase and Oliver Chapman, two real estate investors, visited the region in the early 1880s and purchased six hundred acres for $13,000, they renamed the area Winter Park, hoping to develop it as a resort for wealthy northerners seeking a tranquil place to relax during wintertime. As people began to relocate to Winter Park, local community leaders were eager to build a college for their children’s education and to raise the profile of the town, but the real driving force was the First Congregational Church of Winter Park, led by Reverend Edward Hooker. In the spring of 1885, after submitting its bid to the Florida Congregational Association, Winter Park beat Daytona Beach, Jacksonville, Mt. Dora, and Orange City to become the site of the school, and the new college was named in honor of Alonzo Rollins, an industrialist from Chicago whose leadership donation of land and money amounted to $50,000.

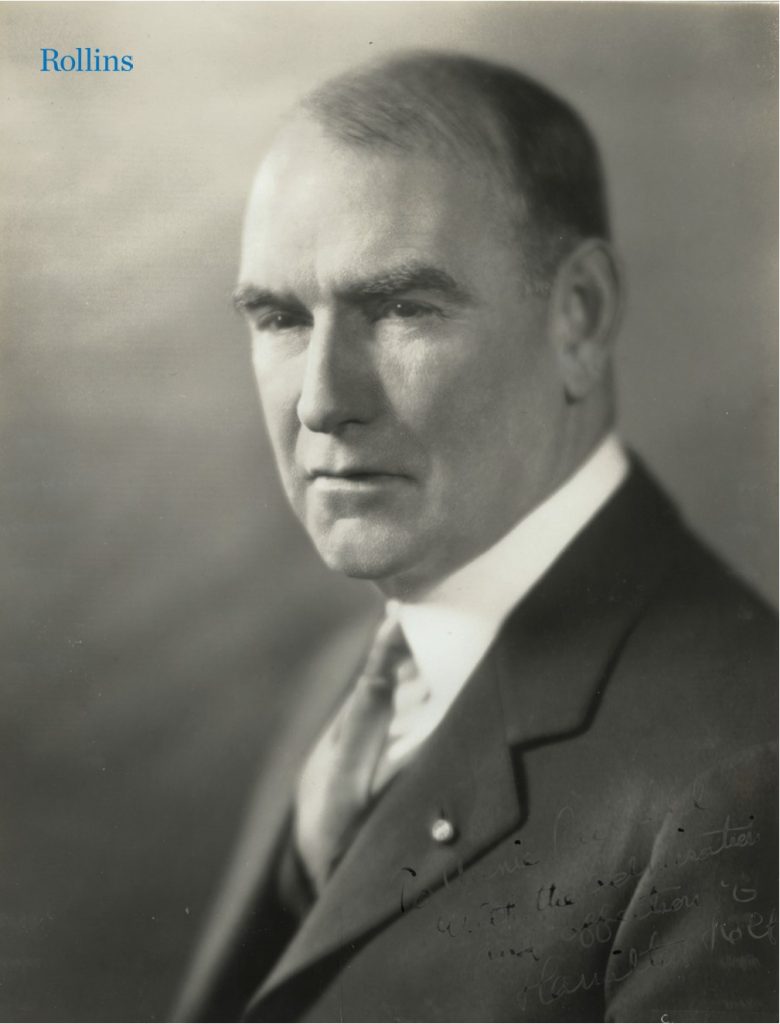

College benefactor Alonzo Rollins (Image: Rollins College Archives)

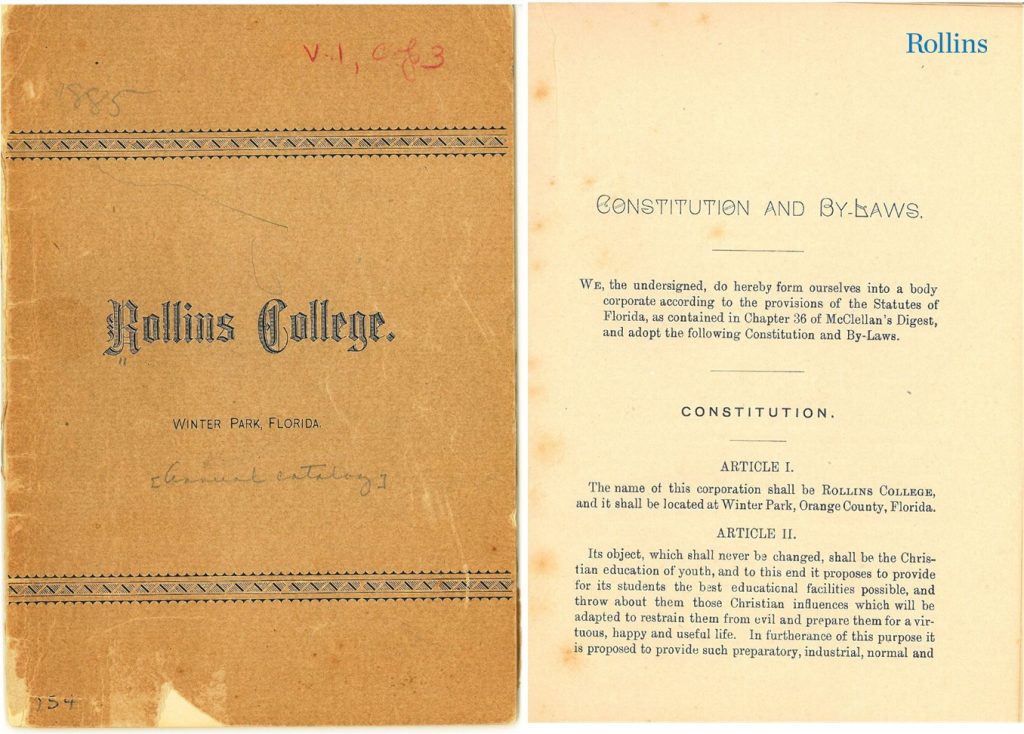

After the Civil War and in the Jim Crow South, Rollins was founded as a segregated, white-only school dedicated to the “Christian education of youth.” Although the College was broadly non-sectarian, religion played a dominant role during its early years. According to the original College Constitution: “Its object, which shall never be changed, shall be the Christian education of youth, and to this end it proposes to provide for its students the best educational facilities possible, and throw about them those Christian influences which will be adapted to restrain them from evil and prepare them for a virtuous, happy and useful life.”[1] Rollins retained its Christian character throughout its early existence and only became an independent institution of liberal arts learning in 1908, when it finally severed its tie with the Congregational Church in Florida.[2]

The cover of the first Rollins catalogue and the college’s first mission statement (Image: Rollins College Archives)

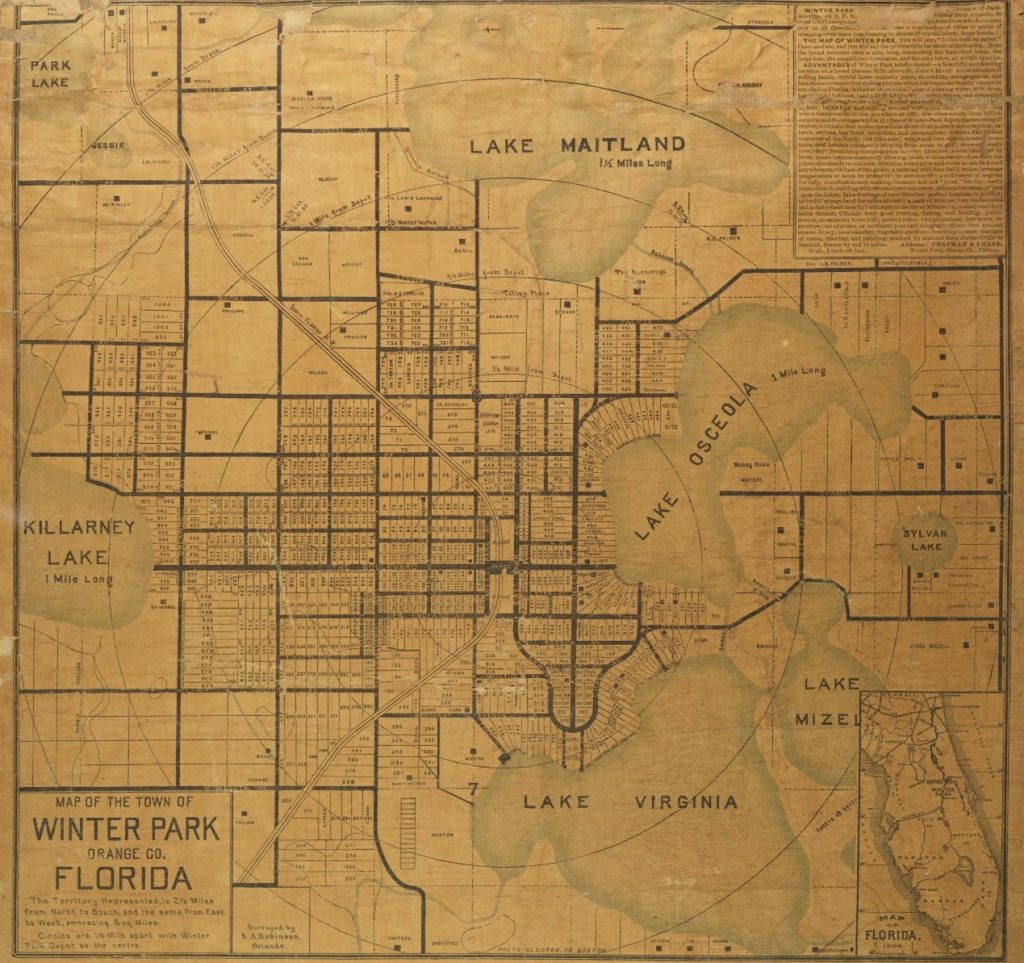

Meanwhile, Winter Park grew together nicely with Rollins in a symbiotic relationship. As a planned community, the railroad track divided the city in two parts: properties in east Winter Park and large lakefront lots were heavily promoted to wealthy visitors from the North, while much smaller lots on the west side were reserved for African American residents who would provide manual labor around the town, working as housemaids or in the orange groves or other local businesses. In 1887, shortly after the founding of the college, Winter Park was officially chartered as a city, and African Americans on the west side played a key role in its incorporation. Local community advocate Gus Henderson rallied the African American residents of Hannibal Square to vote in favor of the incorporation led by Chase and Chapman; as a result, the city also elected two African American aldermen, Walter B. Simpson and Frank R. Israel.[3] However, African Americans’ participation in the municipal affairs of Winter Park was short-lived. Through a gerrymandering scheme in September 1893, local white leaders redistricted the city, cutting out Hannibal Square and its Black Republican residents to benefit Democrats who sought control of the city government.[4] Only after a new charter was adopted in 1925 was the west side reannexed as part of Winter Park.

Winter Park, Florida, in 1884: two Winter Parks divided by the railroad track (Image: Rollins College Archives)

Florida in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries was still a southern frontier state, with a low population and an agricultural economy. Multiple deep freezes, economic recessions, and a pandemic had presented substantial challenges, not only to local residents, but also to college leaders. Throughout its early decades, Rollins never found a sound financial footing and constantly struggled for its survival. During the George Morgan Ward administration and impacted by the Spanish American War, Rollins began to admit students from Latin America in the late 1890s. This measure was not so much mission-driven as largely out of economic necessity; still, this endeavor has been regarded as the beginning of global citizenship education at Rollins. Since Rollins was a white-only school, students’ physical appearance was emphasized. In a recruitment note to Ward dated May 29, 1902, B. L. Gonzalez described a new student who was traveling from Cuba to Rollins: “The boy is 17 years old, white boy and his name is Jose Manuel.”[5]

Cuban students on the Rollins campus, circa 1902 (Photo: Rollins College Archives)

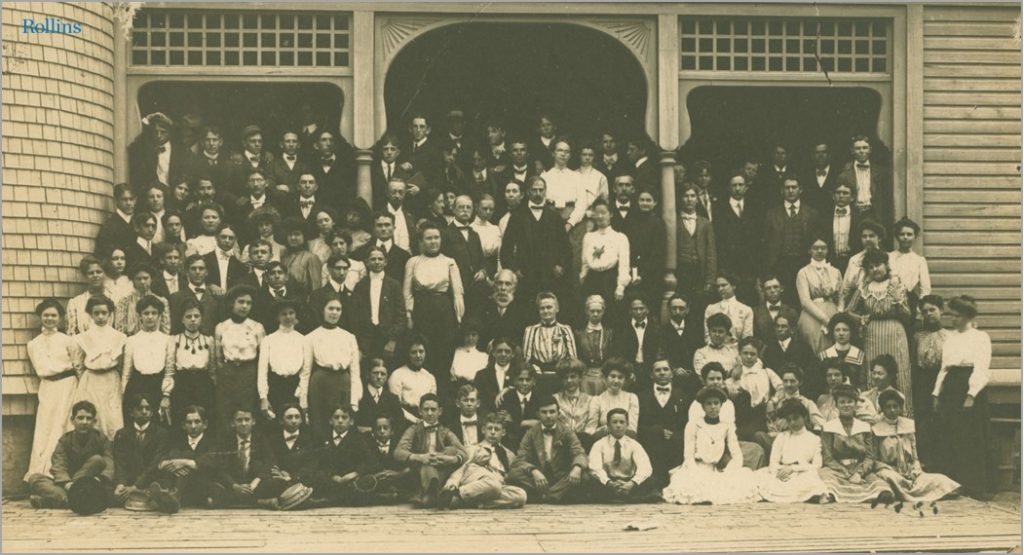

Since the founding of the college in the late nineteenth century, African Americans from west Winter Park were an integral part of the Rollins community. To keep the school running smoothly, they worked in the dining hall, cleaned student dormitories, and maintained campus landscapes; however, when it came to official college functions, as illustrated by this 1901-02 group photo of Rollins faculty, staff, and students posed in front of Knowles Hall, they were nowhere to be found. During social events, such as costume parties, students would sometimes wear blackface, with little regard for the cultural implications of their behavior to African Americans in the community.

Rollins faculty and students in front of the original Knowles Hall, 1901-02 (Photo: Rollins College Archives)

Race Relations During the Holt Era

President Hamilton Holt (Photo: Rollins College Archives)

In 1925, Hamilton Holt (1872-1951) became the eighth president of Rollins, a position he held until 1949, making him the longest-serving president so far in the college’s history. A journalist by training with little theoretical knowledge of higher education, Holt learned from his personal experience as a student at Yale. He was convinced that students’ growth should be the central focus of any educational endeavors, and that an individual must actively engage in his or her own journey of learning. In what he defined as Rollins’ Adventure in Common-Sense Education, Holt persuaded the faculty to abandon the lecture and recitation method and launched the Conference Plan of teaching. With support from famed educational philosopher John Dewey, who chaired the college’s Curriculum Conference in 1931, Rollins began to emerge as a national leader in pragmatic liberal arts education and “the only cosmopolitan college in the South.”[6] To many people in the local community, as Holt’s biographer Warren Kuehl described, “Rollins is Holt, and Holt is Rollins.”[7] Hamilton Holt greatly shaped the development of the college for a large part of the twentieth century.

Rollins’ Conference Plan of teaching, with Prof. Edwin Grover at the head of the first oval table in Carnegie Hall, ca. 1928-29. Also note Wufei Liu on the far left of the classroom. Rollins began to admit students from Asia in the late 1920s, and in 1946, Dr. Wu-Chi Liu became the first faculty member of Asian heritage to teach at Rollins.

Hamilton Holt took a very liberal stand on the social policies and race relations of his time. His grandfather, Henry C. Bowen, was an original founder of The Independent, a weekly religious publication devoted to antebellum abolitionism. After Holt became the managing editor in 1897, he turned the magazine into a national progressive voice on social, economic, and political issues. With a deep concern for equality at the turn of the century, he published many personal stories in The Independent to portray those struggling at the bottom of the social ladder, including African Americans, Native Americans, and immigrants. Sixteen of those profiles were later compiled into The Life Stories of Undistinguished Americans, as Told by Themselves.[8] In 1909, along with other notable progressives, such as W. E. B. Du Bois, Ida B. Wells-Barnett, Jane Addams, Florence Kelley, John Dewey, Charles Darrow, and Oswald Villard, Holt became a founding member of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP).[9] Believing in equity for all and that segregation was morally wrong and must be corrected, he strongly condemned the racial discrimination and violence against Blacks in the South, noting that not even German ferocity in Belgium, English cruelty in Ireland, and Japanese brutality in Korea could “equal in depravity and barbarity America’s record for lynching.”[10]

As an accomplished journalist and marketing genius, Hamilton Holt launched the Rollins Animated Magazine, an annual public speaking event that brought many great personalities to Rollins. Again, no African Americans can be seen in the large audience gathering on Sandspur Field in 1941. (Photo: Rollins College Archives)

While working for The Independent, Holt visited the trenches in Europe at the end of World War I. Shocked by the mass casualties of modern warfare, he became an ardent internationalist and devoted his life to the international peace movement. He even erected a Peace Monument on campus in the late 1930s, only to see it vandalized during World War II. As a dedicated peace advocate, Holt strongly opposed any forms of violence. He firmly believed that engagement and dialogue would be the best way to solve any conflicts in both international and domestic affairs. After living in Florida, he also adopted a moderate position on race relations, convinced that desegregation would be best achieved by gradual programs instead of through drastic changes imposed by the federal government. In 1947, he joined eight other presidents in the South to voice objections to the recommendation by the Truman Commission that the dual system of schools in seventeen states be eliminated: “It would be unwise and impractical to end the segregation of white and negro children that exists in the schools and colleges of the South, by any kind of government edict. This problem should be solved by the Southern people themselves and cannot be done overnight.”[11]

Needless to say, Holt was not a saint, but a complex human being. To gain a more comprehensive understanding of Holt and Rollins during the first half of the twentieth century, in the following sections we will look at several key events and people—including students, faculty, and staff—to shed light on the progress of race relations during the Holt era.

Zora Neale Hurston’s Afro-American Folklore Performances at Rollins

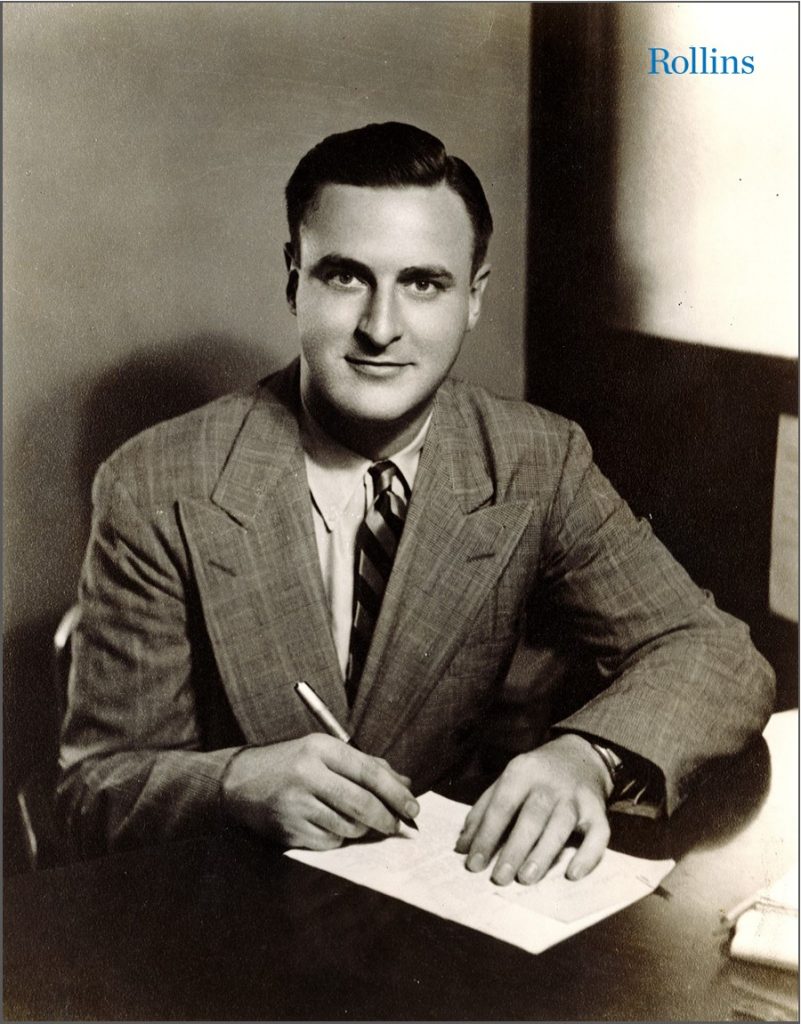

Described as “a genius of the South,” Zora Neale Hurston was a famed African American author and anthropologist. Growing up in Eatonville, Florida, Hurston also had a strong personal connection with Rollins, as she dedicated two of her novels to Edwin Grover (Moses, Man of the Mountain) and Robert Wunsch (Jonah’s Gourd Vine), two Rollins faculty members who helped relaunch her literary career in the 1930s. Retreating from the Harlem Renaissance, Hurston had come back to Central Florida to figure out the next chapter of her life. When she visited The Bookery, the first bookstore in Winter Park, she met and befriended Edwin Grover, Professor of Books at Rollins. Upon reviewing her draft of Mules and Men, Grover was deeply impressed. He gave her practical advice and recommended the manuscript to his contacts in publishing circles. Grover also introduced Hurston to Robert Wunsch, a young theatre professor at Rollins who had a strong interest in African American performing arts and sought new ways to broaden students’ horizons in creative learning.

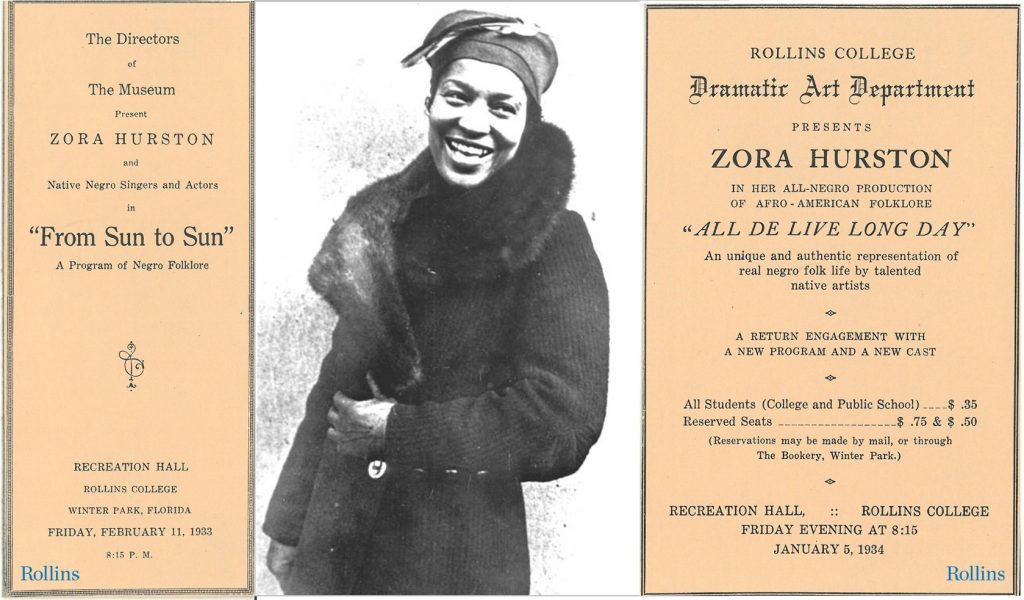

Original playbills of Hurston’s Afro-American Folklore productions: FROM SUN TO SUN (February 11, 1933) and ALL DE LIVE LONG DAY (January 5, 1934). Both took place in the Recreation Hall at Rollins. (Images of playbills: Rollins College Archives; Photo: State Archives of Florida)

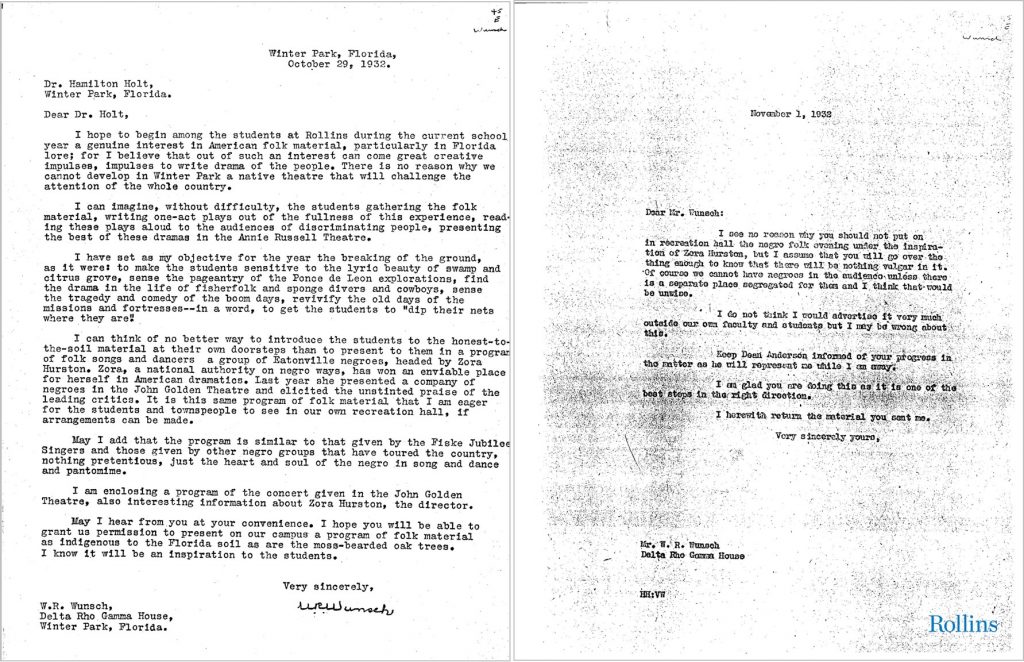

After inviting Hurston for a guest lecture on African American folklore in Fall 1932, Wunsch proposed to schedule a large public program at Rollins. On October 29, 1932, Wunsch wrote to Holt, passionately arguing that Hurston’s performance would be a great learning opportunity for Rollins students. “I can think of no better way to introduce the students to the honest-to-the-soil material at their own doorsteps than to present to them in a program of folk songs and dancers a group of Eatonville negroes, headed by Zora Hurston. Zora, a national authority on negro ways, has won an enviable place for herself in American dramatics.”[12] In his memo three days later, Holt’s response was very measured. While praising the program as “one of the best steps in the right direction,” Holt wrote: “I see no reason why you should not put on in recreation hall the negro folk evening under the inspiration of Zora Hurston, but I assume that you will go over the thing enough to know that there will be nothing vulgar in it. Of course we cannot have negroes in the audience unless there is a separate place segregated for them and I think that would be unwise. I do not think I would advertise it very much outside our own faculty and students but I may be wrong about this.”[13]

Prof. Robert Wunsch and President Hamilton Holt’s correspondence concerning Zora Neale Hurston’s programs at Rollins, 1932 (Image: Rollins College Archives)

With Holt’s cautious support, Hurston’s production was successfully held in the Recreation Hall at Rollins and received rave reviews, not only from The Sandspur, but also from local newspapers, such as the Orlando Morning Sentinel and the Winter Park Herald.[14]

This cultural performance also had a profound impact on Bucklin Moon (1911-1984), Class of 1934 and editor of the Flamingo, a student literary magazine at Rollins. Inspired by Hurston, Moon decided to pursue a literary career, with a focus on the lives of African Americans. After graduating with a major in history, Moon became a literary editor in New York, first at Doubleday and then at Collier’s. His first book The Darker Brother (1943) traced the life of a young Black man who left Winter Park for Harlem in search of the promised land. With A Primer for White Folks in 1945, Moon became the first white author to publish an anthology of writing by and about Black America. After publishing an economic analysis in The High Cost of Prejudice in 1947, Moon authored his finest work, Without Magnolias, an account of a Black family in Winter Park and Orlando, which received the George Washington Carver Award for the best book of 1949 by or about Blacks. Unfortunately, two years later Moon was wrongly accused by the House Un-American Activities Committee of supporting the Communist Peace Offensive. Despite various protests against such charges, Collier’s fired Moon in 1953. Unemployed, divorced, depressed, and suicidal, Moon’s life and booming writing career were suddenly destroyed by the chilling McCarthyism in American politics.[15]

Bucklin Moon ’34 (Photo: Rollins College Archives)

Golden Personalities

In his efforts to develop Rollins into a premium institution in liberal arts education, Holt believed it was professors who make a college great, and he dedicated himself to securing so-called Golden Personalities as faculty members: “men and women of learning whose sole love was teaching, who enjoyed associating with young people, individuals with noble characters.”[16] Nevertheless, not every faculty member recruited by Holt turned out to be golden, among them John Rice, professor of classical studies and a former Rhodes scholar whom Holt had to fire after only two years. The dismissal led to protests by other faculty members and additional firings by Holt in 1933, resulting in a formal investigation and censure by the American Association of University Professors. Another result of “the Rice Affair” was the founding of Black Mountain College in North Carolina by dismissed Rollins faculty members, led by John Rice and Robert Wunsch.[17] Although the Rice Affair was a major moment of crisis in the college’s history, a few other professors stood out prominently in terms of the development of race relations during Holt’s tenure at Rollins.

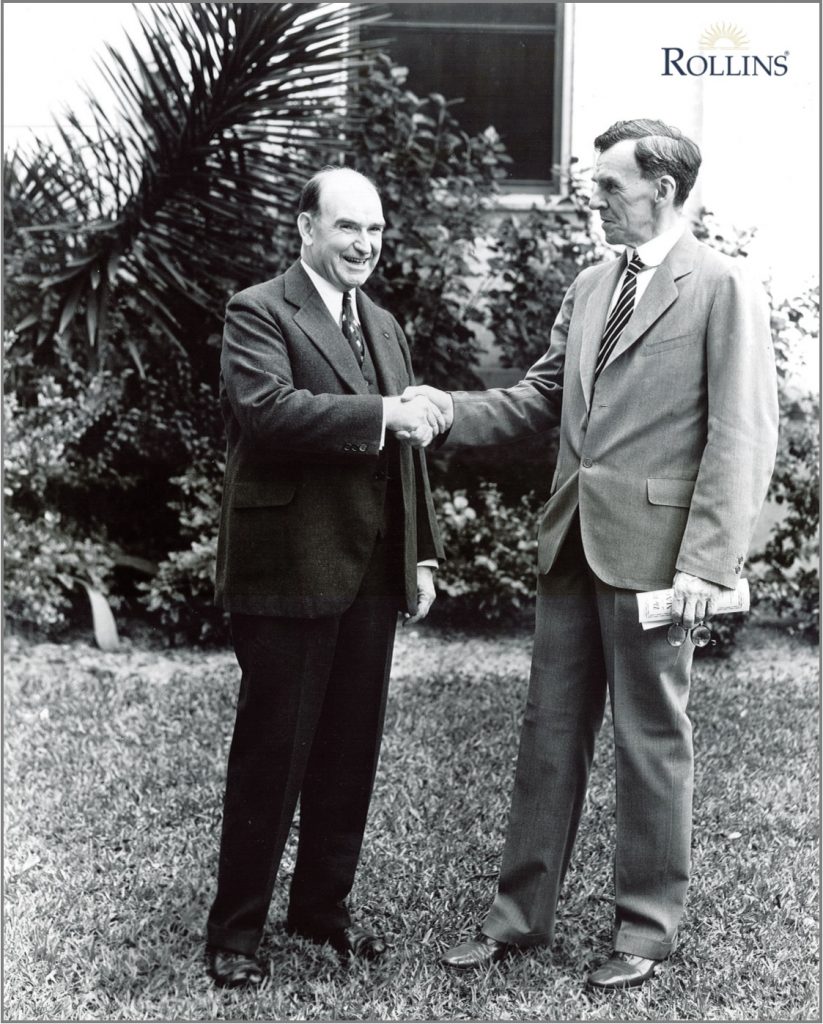

President Hamilton Holt and Professor of Books Edwin Grover (Photo: Rollins College Archives)

Edwin Grover (1870-1965) was the first faculty appointment made by Holt when he became Rollins’ president. With more than thirty years’ experience in publishing, Grover held the unique title of Professor of Books and regularly taught three courses: The History of Books, Literary Personalities, and Recreational Reading. Through active, collaborative learning with students, Grover assisted Holt in the development of the Conference Plan of teaching at Rollins. With Holt being the publisher, Grover served as the editor of the Rollins Animated Magazine for more than two decades. As noted earlier, Grover was very instrumental in supporting Zora Neale Hurston’s literary career. He also helped students launch Rollins’ first literary magazine, the Flamingo, in 1927 and worked with librarian William Yust to establish the Book-A-Year program in 1933, the first book endowment for the college library.

In community affairs, Grover was also a remarkable citizen in Winter Park. He was a charter member of the University Club of Winter Park, and helped found The Bookery. He was also the driving force behind the founding and development of Mead Botanical Garden. More significantly, Grover played a major role in the improvement of race relations in Central Florida, serving as a trustee of Bethune-Cookman College for many years. To help local African American residents, he and his wife, Mertie, along with Mrs. Clarence Vincent, launched a day nursery for children of Black working mothers in Winter Park. When Mertie died following a traffic accident in 1936, instead of flowers, Grover requested donations for the establishment of a children’s library on the west side. When the Hannibal Square Associates was incorporated the following year, Grover served for ten years as its first president. In that capacity, he raised thousands of dollars for the development of the West Side Community Center, the Hannibal Square Memorial Library, and the Mary DePugh Nursing Home in Winter Park.[18]

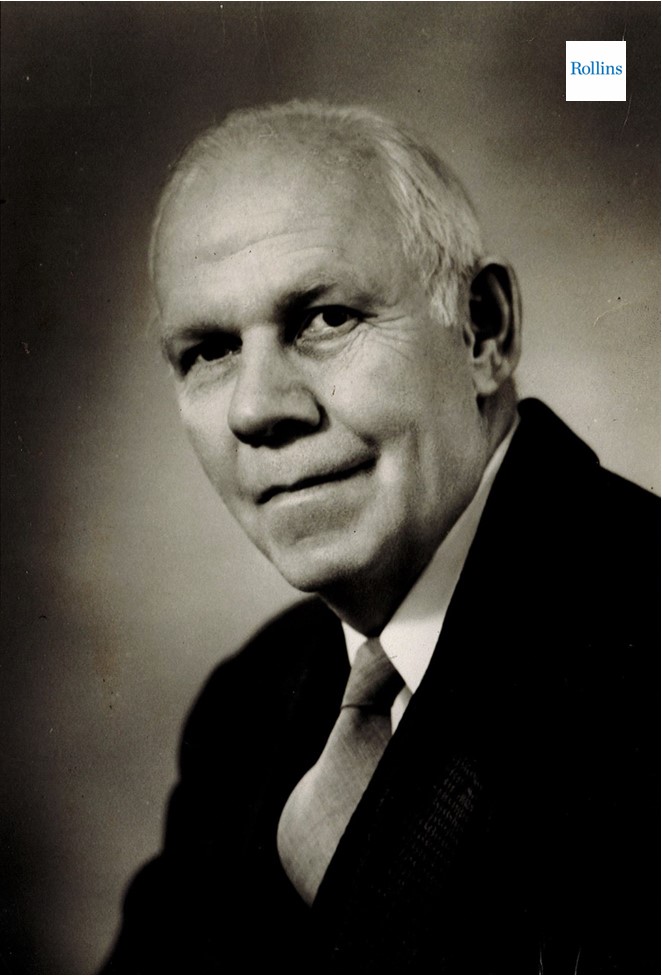

Prof. Royal France (Photo: Rollins College Archives)

Royal Wilbur France (1883-1962) was another of Holt’s original Golden Personalities. A graduate of George Washington University and Hamilton College, France was a lawyer by training. Before joining Rollins as a professor of economics in 1929, he was a veteran business executive who understood labor issues and deeply sympathized with the struggles of working-class Americans. In 1936, France published a novel entitled Compromise, in which he outlined “the story of an idealist’s moral battle against the pressure of circumstances of his day.”[19] While the book brought fame to France and led to his appointment as chairman of the Florida Socialist Party, the generally conservative public in the Deep South called for his dismissal, which President Holt had to fend off.

In the summer of 1939, France’s son, H. Boyd France ’41, and Boyd’s friend, J. Roderick MacArthur ‘42, were arrested in the African American neighborhood of Parramore under the Florida Vagrancy Statute. France bravely fought the Orlando Police Department for their discriminatory measures and civil right violations and filed a grievance with U.S. Attorney General Frank Murphy.[20] In his autobiography My Native Grounds, France also recalled his family’s friendship with Zora Hurston in the 1930s: “Zora spent the night with us, and the news spread rapidly. We had committed the sin of sins and were to be punished for it.”[21] When the McCarthy terror began to unfold, France announced his retirement from teaching, became a consultant to the American Civil Liberties Union, and devoted his life to defending those wrongly accused in the anti-communist crusade.

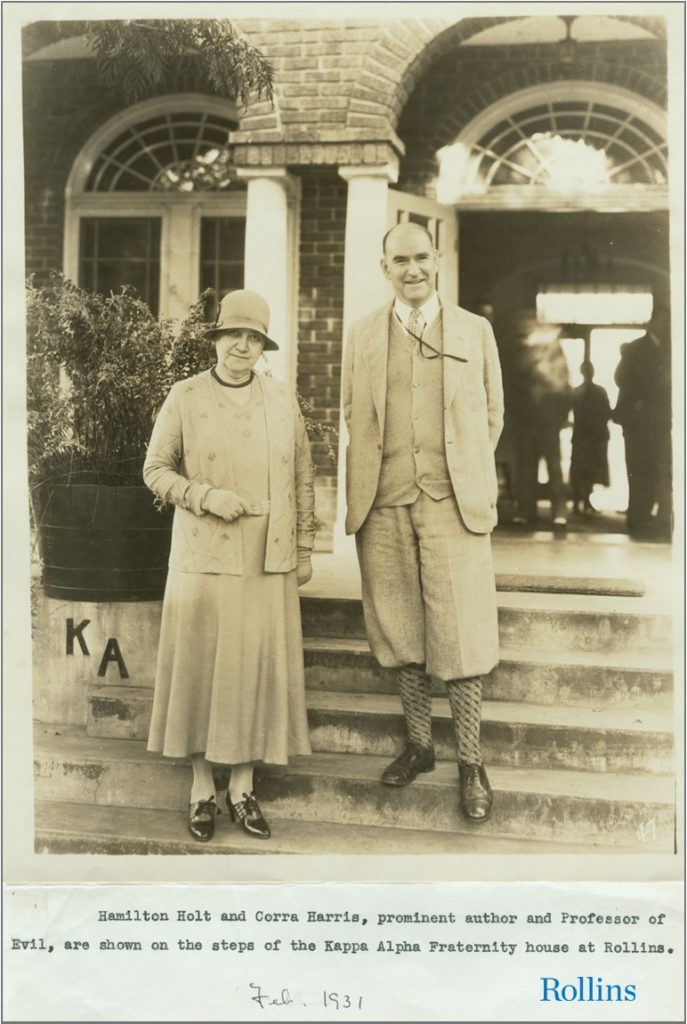

Corra Harris ’27H and President Hamilton Holt (Photo: Rollins College Archives)

Corra Mae Harris (1869-1935) was an American writer, journalist, and frequent contributor to The Independent. Unlike Holt’s other notable Golden Personalities, who took very progressive stands on social issues, Harris was a vocal segregationist and white supremacist. A Georgia native and a pastor’s wife, Harris received very little formal education growing up. She began her writing career with an apologia essay titled “A Southern Woman’s View,” in which she passionately defended the lynching of Sam Hose (Thomas Wilkes), an alleged violent offender. Although Holt disagreed with Harris’s views personally, he was impressed by her writing and decided to publish her justification for lynching and segregation, along with a response from W. E. B. Du Bois, in the May 18, 1899, issue of The Independent.[22] This began a personal friendship between Harris and Holt that lasted for more than three decades, until Harris’s death.

After publishing multiple articles in The Independent, Harris went on to become a well-known novelist, an accomplished journalist, and a very productive essayist and literary critic. Proud of his role in launching Harris’s writing career, Holt awarded her a Doctor of Humane Letters degree in 1927 and invited her to guest lecture at Rollins in 1929-30 on philosophical issues, such as virtue and morality. Known as the “Professor of Evil,” Harris’s course received a great deal of publicity. Harris also appeared several times as a featured speaker in the Animated Magazine and authored The Town That Became a University, in which she described Winter Park as a “University at Large” and praised Holt’s efforts in making Rollins a laboratory in liberal arts education.[23]

The 1947 Rollins/Ohio Wesleyan Football Game

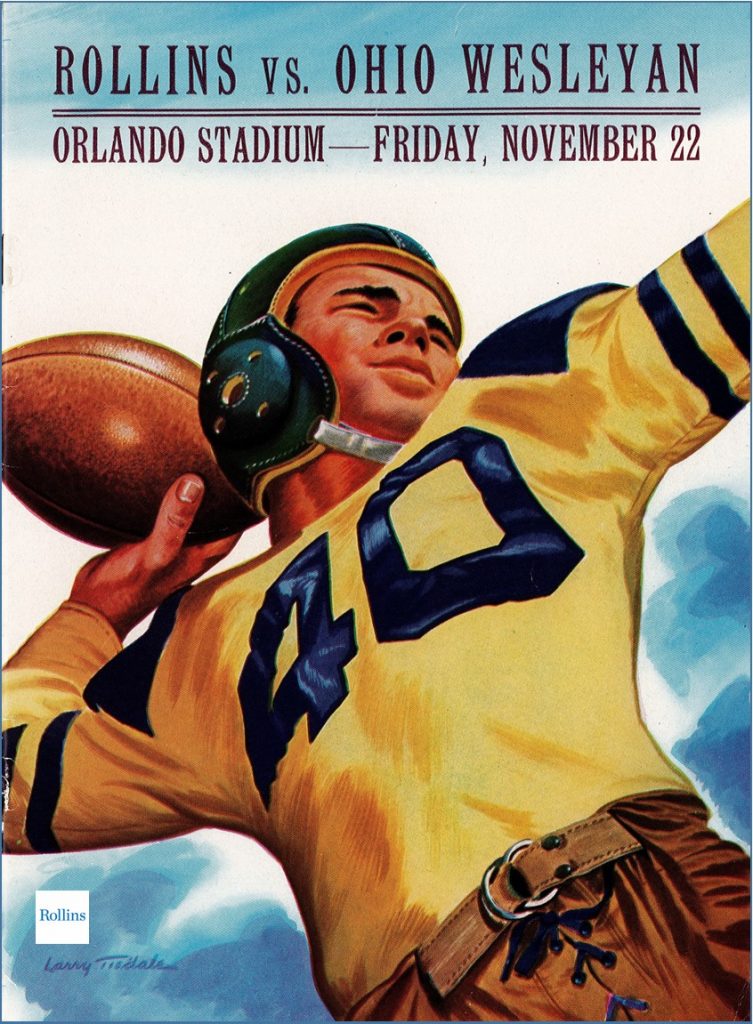

The front cover of the 1946 Rollins/Ohio Wesleyan homecoming football program (Image: Rollins College Archives)

For the first half of the twentieth century, Rollins had a very active football program, as the popular sport provided a common experience for the campus community, and its annual ritual was the homecoming celebration held in the Orlando Municipal Stadium each November. After Rollins beat Ohio Wesleyan University (OWU) 21-13 in 1946, the next homecoming game was set for November 28, 1947. However, five weeks before game time, Rollins learned the new OWU team included an African American freshman player named Kenneth Woodward. That dilemma presented a major challenge to Rollins and Holt, since state law still prohibited mixed participation in any educational programs.

Despite notable social progress since World War II, Florida in the late 1940s remained a frontier state in terms of race relations. Historically, Central Florida was a hotbed for racially motivated hate crimes. The Ocoee Massacre of November 2, 1920, was described as the “bloodiest day in modern American political history,”[24] and the Orlando Sentinel had frequent coverage of Klan activities, such as cross burning, in the region. When Jackie Robinson arrived in Central Florida for his first spring training with the Montreal Royals in 1946, he was forced to sit in the back of the bus and humiliated, and the Sanford police chief stopped a minor league game because of his presence.[25] On top of that, the Orlando Municipal Stadium was managed by the local chapter of the American Legion, a conservative veterans’ organization established after WWI. Active in issue-oriented politics and seeking to promote the ideology of Americanism, some of its followers were also members of the Ku Klux Klan. Around the same time, the Florida NAACP also passed a resolution in 1947 noting that “The existence of Ku Kluxism is a potential threat to the personal safety and the Constitutional rights of all minorities. We therefore ask our state, county, and city authorities to take vigorous action in cases of intimidation or violence against citizens by the Ku Klux Klan and other Fascist groups.”[26]

As a small liberal arts college, Rollins faculty and students had long supported progressive racial politics. Nevertheless, the 1947 Rollins/OWU football game had set that racial progressivism on a direct collision course with the reality of white supremacy in the segregated South. During the first half of the twentieth century, to maintain the racial status quo, white southern college leaders contractually agreed that the color line would be maintained on athletic fields. Through a so-called gentlemen’s agreement, white southern institutions avoided integrated competition by not scheduling games with integrated teams from the North or by insisting those teams leave their Black players behind. However, things finally began to change in the late 1940s; sports were used by brave leaders to challenge the political environment and eventually led to social changes and the Civil Rights Movement years later. A most notable example was the integration of Major League Baseball in 1947, when Jackie Robinson joined the Brooklyn Dodgers. When Ohio Wesleyan, led by Branch Rickey, general manager of the Dodgers, insisted on bringing its African American player to the game, President Hamilton Holt failed to take a stand against racial injustice and cancelled the game, fearing that potential violence would set back social progress in the South, even though the cancellation was against his personal beliefs.[27]

On Friday, November 28, when the homecoming game was supposed to take place, Holt gathered students and faculty in the Annie Russell Theatre to give a lengthy speech and turned the difficult situation into a teaching moment. “May I say this to you students: you will probably have critical decisions like this to make as you go through life—decisions that whatever you do, you will be misinterpreted, misunderstood, and reviled. I have found in my own case it helps to find out which of your loyalties involved is the greater. It seemed to all of us that our loyalties to Rollins and its ideals were not to precipitate a crisis that might and probably would promote bad race relations, but to work quietly for better race relations, hoping and believing that time would be on our side.”[28]

Mary McLeod Bethune and Susie Wesley

Educator and civil rights leader Mary McLeod Bethune, circa 1943 (Photo: State Archives of Florida)

The 1947 Rollins/Ohio Wesleyan University football game that never took place was a defining moment in the history of the College in terms of race relations. The event also had a profound impact on Holt personally and the last two years of his presidency. Although he strongly supported the cause of African Americans, his peace ideology and opposition to any violence in conflict resolution held him back from taking a brave stand against racial discrimination in America. However, in private correspondence, Holt admitted, “It was a sickening decision for me to make and it is quite possible that if we had gone ahead nothing would have happened.”[29] “We may have made a mistake, but it is one of those cases where you are damned if you do and damned if you don’t.”[30]

To correct his mistake, Holt proposed to award an honorary degree to Mary McLeod Bethune, famed African American educator, civil rights leader, and Holt’s friend since the early twentieth century. Bethune, the first African American to speak from the Rollins platform, had been invited by Holt to lecture in the college chapel on March 6, 1931.[31] However, since no southern school had ever awarded an honorary degree to an African American, his proposal was rejected by the college’s conservative Board of Trustees. Deeply frustrated, Holt threatened to resign in protest. It was Bethune who declined: “Your college and the state of Florida need men like you. And while I appreciate the honor that you pay me, I believe far more good will be accomplished by your remaining president of the college than by anything I could possibly say in 15 or 20 minutes of speechmaking. With you at the college helm, there will come a day when attitudes will be different.”[32]

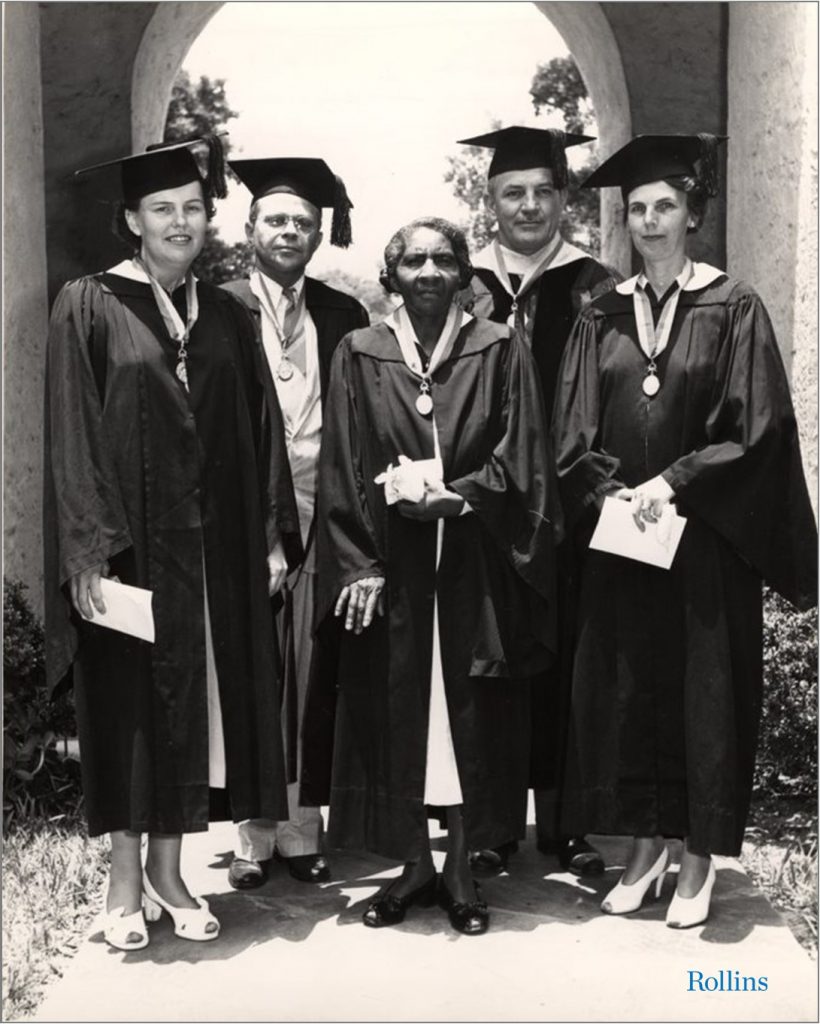

Despite the setback, Holt was determined to make a difference this time. During Commencement on June 2, 1948, he used his authority as college president to award the Rollins Decoration of Honor to Susie Wesley, a beloved African American housemaid since 1924—the first Decoration of Honor ever awarded to an African American in the history of the college. “Susie Wesley, for your many years of faithful service to Rollins, during which you and I have both worked for the College that we love; for your help to many hundreds of Rollins freshman girls; for your influence in Winter Park through church and club; for your generous service far beyond the call of duty; for your life as a Christian woman and a loving follower of our Lord Jesus Christ, Rollins College is honored in conferring on you the Decoration of Honor and admits you to all its rights and privileges.”[33]

Susie Wesley (center), recipient of the Rollins Decoration of Honor, 1948 (Photo: Rollins College Archives)

When Holt decided to retire in 1949, one of his last actions as college president was to publicly honor his friend Mary Bethune at Rollins. During the Founder’s Day celebration on February 21, 1949, with thousands gathered in Sandspur Field, Holt personally presented an honorary Doctor of Humanities degree to the African American educator and civil rights leader: “Mary McLeod Bethune, I deem it one of the highest privileges that has come to me as President of Rollins College to do honor to you this morning. I am proud that Rollin is, I am told, the first white college in the South to bestow an honorary degree upon one of your race.”[34] In the end, despite his own limitations and surrender to political pressures in the segregated South, Holt ultimately was able to stand on the right side of history and make his mark on social integration in the United States.

Hamilton Holt and Mary McLeod Bethune ’49H, 1949 (Photo: Rollins College Archives)

Fred Rogers, Everyone’s Favorite Neighbor

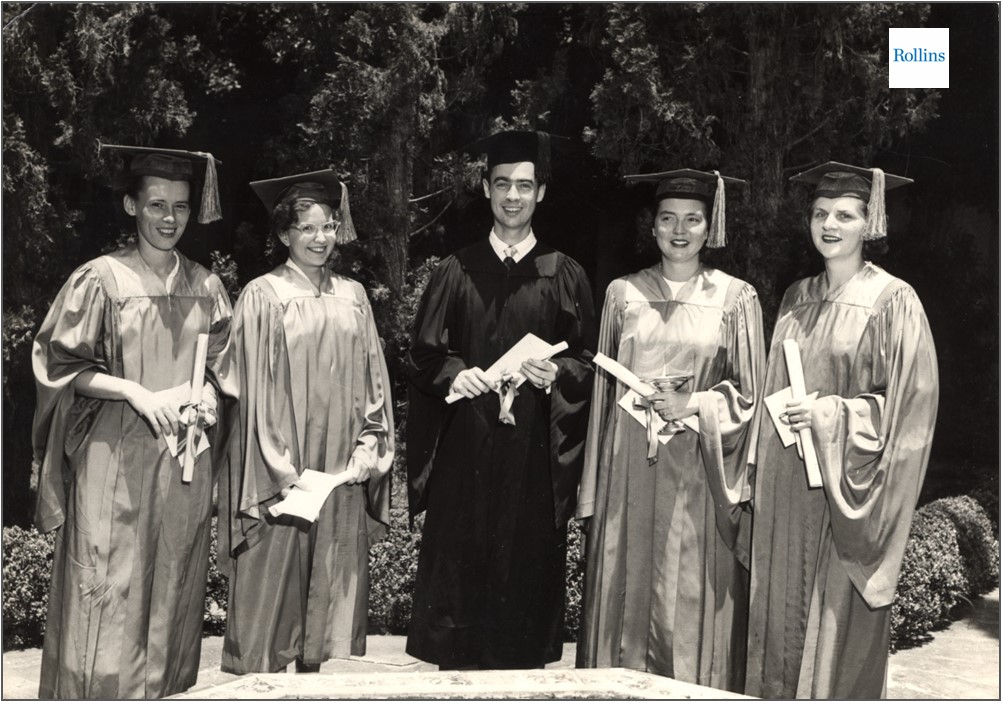

Fred Rogers (center) and fellow award winners at Commencement, 1951 (Photo: Rollins College Archives)

Fred McFeely Rogers ’51 ’74H, the creator and host of the children’s television program Mister Rogers’ Neighborhood, is one of Rollins’ most beloved alumni. After transferring to Rollins from Dartmouth in 1948, Fred Rogers excelled academically and graduated with Distinction, earning a degree in music composition in 1951. At his commencement, Rogers received an award for composition and the General Charles McCormick Reeve Award for scholarship. Besides being the president of Alpha Phi Lambda and the French Club, he was also a member of the Key Society (Rollins honor society), Pi Kappa Lambda (American honor society for music), the Bach Choir, Chapel Choir, and the Student Music Guild. Although his life and professional accomplishments after graduation are well known, not too many people are aware that Fred Rogers also had very progressive viewpoints on race relations in America while studying at Rollins. In her 2019 essay, “The Radical Mister Rogers,” Chantel Tattoli ’09 examines the role Rollins and Central Florida played in Rogers’ life and legacy, with a special focus on his political activism.[35]

A recognized student leader at Rollins, Fred Rogers’ work as chair of the Rollins Inter-Faith and Race Relations Committee merits special note. Established during the Holt era, this was a student organization that “cooperates with the local Interracial Relations Committee in practical projects, studies and discusses the many race problems, and participates in state and national conferences.”[36] His four-page, handwritten report documented the group’s activities in 1950-51, which included collecting and sorting books for the Eatonville community, raising funds for the DePugh Nursing Home for African Americans, working with a local electric company to have fluorescent lighting installed at the Hannibal Square Library on the west side of Winter Park, wrapping Christmas presents for needy families, attending a cultural program at Bethune-Cookman College in Daytona Beach, and organizing Race Relations Sunday at the Annie Russell Theatre on February 11, 1951—the seventh annual inter-faith event, which featured the Hungerford School Choir and “a stirring address” by Rabbi Morris Lazaron.[37] The Committee also hosted a Thanksgiving party with ice cream and cakes for ninety-six African American children at the local nursery and kindergarten, who in return chanted “turkey and pumpkins songs” for Rollins students. Fred Rogers was deeply moved by this personal experience, noting, “They gave us a lot more than they ever dreamed of giving.”[38]

[1] “Constitution and Bylaws.” Rollins College General Catalogue (Winter Park, FL: Rollins College, 1885), 13-14.

[2] “President William Fremont Blackman and His Administration 1902-1915,” Rollins Bulletin, Rollins College Archives, Winter Park, Florida, 24-25. Https://scholarship.rollins.edu/archv_books/17/.

[3] “Gus C. Henderson: Hard Working and Determined – He Brought the News to Winter Park.” Winter Park Public Library, http://archive.wppl.org/wphistory/ghenderson.html.

[4] “It’s a Scheme.” September 23, 1893. Winter Park Scrap Book 1881-1906: Loring Chase Scrapbooks Vol. 1.

[5] Susan Montgomery, “The Roots of Global Citizenship: Rollins’ First Latin American Students, 1896-1897.” From the Rollins College Archives, https://blogs.rollins.edu/libraryarchives/2016/10/11/the-roots-of-global-citizenship-rollins-first-latin-american-students-1896-1897/.

[6] Jack C. Lane, “The Holt Era: Building a Liberal Arts College.” Rollins College: A Pictorial History (Winter Park, FL: Rollins College, 1980), 52.

[7] Warren F. Kuehl. Hamilton Holt: Journalist, Internationalist, Educator (Gainesville, FL: University of Florida Press, 1960), 219.

[8] Hamilton Holt, The life Stories of Undistinguished Americans as Told by Themselves (New York: James Pott, 1906).

[9] Kuehl, 48.

[10] Ibid.

[11] Benjamin Fine, “Southerners Hit Education Report: College Leaders on Truman Commission Form Minority on Ending Segregation.” New York Times, December 23, 1947.

[12] Robert Wunsch to Hamilton Holt, October 29, 1932. Rollins College Archives. Winter Park, Florida.

[13] Hamilton Holt to Robert Wunsch, November 1, 1932. Rollins College Archives. Winter Park, Florida.

[14] Maurice J. O’Sullivan, Jr., and Jack C. Lane, “Zora Neale Hurston at Rollins College,” in Steve Glassman and Kathryn Lee Seidel (eds.), Zora in Florida (Gainesville, FL: University Press of Florida, 1991), 130-145.

[15] Bucklin Moon Manuscript Collection, Rollins College Archives. Winter Park, Florida. https://lib.rollins.edu/olin/oldsite/archives/moon.htm.

[16] Lane, Rollins College: A Pictorial History, 53.

[17] Jack C. Lane, “Chapter 6: A College in Crisis (The Rice Affair), 1933.” Rollins College: A Centennial History (Winter Park, Florida: Rollins College,2017). https://scholarship.rollins.edu/mnscpts/6/.

[18] Wenxian Zhang, “Professor of Books.” Reflections from Central Florida 3:2 (April 2005): 4-5.

[19] Irving Bacheller, “Royal W. France,” News Service, 1. Rollins College Archives. Winter Park, Florida.

[20] Jack C. Lane, “The Case of the ‘Embryo Artist’ and Vagrancy Laws in Segregated Orlando, 1939.” Rollins College Archives. Winter Park, Florida.

[21] Royal France, My Native Grounds (New York: Cameron, 1957), 75. https://scholarship.rollins.edu/as_facpub/115/.

[22] Jack C. Lane, “The Complicity of Silence: Race and the Hamilton Holt – Corra Harris Friendship, 1899-1935.” The Independent 2:2 (2015), 18- 24. https://scholarship.rollins.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1221&context=as_facpub.

[23] Corra Harris, The Town That Became a University (Winter Park: Florida, 1930).

[24] Paul Ortiz, “Ocoee, Florida: Remembering the Single Bloodiest Day in Modern U.S. Political History.” Facing South: A Voice for a Changing South, May 14, 2010. https://www.facingsouth.org/2010/05/ocoee-florida-remembering-the-single-bloodiest-day-in-modern-us-political-history.html.

[25] Martin Comas, “Sanford Park No Longer Honors Chief Who Booted Jackie Robinson from Game Because of Race.” Orlando Sentinel, August 11, 2020.

[26] Harry T. Moore, “Resolutions Adopted by the Florida State Conference, NAACP, Lake Wales.” November 1947.

[27] Wenxian Zhang, Raja Rahim and Julian Chambliss, “Race and Sport in the Florida Sun: The Rollins/Ohio Wesleyan Football Game of 1947.” Phylon 56:2 (2019): 59-81.

[28] “Remarks by Hamilton Holt at the Annie Russell Theatre.” November 28, 1947. Rollins College Archives, Winter Park, Florida.

[29] Hamilton Holt to John Van Metre, December 12, 1947. Rollins College Archives, Winter Park, Florida.

[30] Hamilton Holt to Marlen Neumann, January 16, 1948. Rollins College Archives, Winter Park, Florida.

[31] “Negro Woman Held Chapel Spellbound: Mrs. Bethune has Sympathy of Audience.” Sandspur, March 11, 1933, 1 & 3.

[32] Mary McLeod Bethune, “My Rendezvous with Democracy.” in Chiazam Ugo Okoye (ed.), Mary McLeod Bethune: Words of Wisdom (Bloomington: IN, AuthorHouse, 2008), 138-140.

[33] “Susan Wesley Decoration of Honor Citation.” June 2, 1948. Rollins College Archives, Winter Park, Florida.

[34] “Mary McLeod Bethune Honorary Degree Citation.” February 21, 1949. Rollins College Archives, Winter Park, Florida.

[35] Chantel Tattoli, “The Radical Mister Rogers,” The Paris Review, December 3, 2019. https://www.theparisreview.org/blog/2019/12/03/the-radical-mr-rogers/.

[36] “Race Relations.” Tomokan (Winter Park, Florida: Rollins College, 1951), 132. https://archive.org/details/tomokan1951roll/page/132.

[37] Fred Rogers, “Report for 1950-51.” Rollins College Archives, Winter Park, Florida. https://archives.rollins.edu/digital/collection/archives/id/623/rec/9.

[38] Ibid.

1 thought on “Pathway to Diversity – The History of Race Relations at Rollins: A Brief Overview from the Archives, Part One (1885-1951)”