by Mickayla Grasse-Stockman ’22

A women’s march in Washington, DC, 1970 (Photo: Library of Congress, via Wikimedia Commons)

In celebration of women’s history, we are pleased to present the fourth and final installment in a series of blog posts written by students in Prof. Claire Strom’s Fall 2020 class, Researching American History. The Archives staff is grateful to Prof. Strom and her students for sharing their work with us.

*****

During the 1960s and 1970s, the United States was thrust into a new era of political consciousness. As women became aware of the inequalities, they faced within society some organized politically to ensure equal rights at the federal level. Through their activism, they passed laws that laid the foundation for gender equity in education. These polices and the growing need to understand women outside of their societal roles created the demand for the creation of women’s studies. The women’s studies program at Rollins College, throughout its first two decades, was established and developed due to the influence of these social and political trends and the increasing academic interest of faculty in these areas.

The political organization of the women’s movement in the 1960s and 1970s created polices that brought the goal of gender-equity into academic institutions. In response to the inherent inequalities between men and women within society, members of the women’s movement organized politically in hopes of eradicating discrimination in employment and education specifically.[1] Their first success was the addition of gender as a category protected against discrimination in President Johnson’s executive order on Affirmative Action in 1968. This policy called for “all government contracting agencies” to “take affirmative action” against discrimination. [2] By receiving federal funds, public colleges were under obligation to adopt their own affirmative action policies. The second success was the addition of Title IX in the Education Amendments of 1972.[3] This policy outlawed discrimination “on the basis of sex within any education program receiving federal financial assistance.”[4] This created an incentive for public initiations to show that they were upholding gender-equity. The third success was the passage of the Women’s Educational Equity Act of 1974.[5] This policy helped “advance gender equity and develop strategies to assist [local educational agencies] in evaluating, disseminating, and replicating gender-equity programs.”[6] These policies brought the discussion of gender-equity into academic institutions.

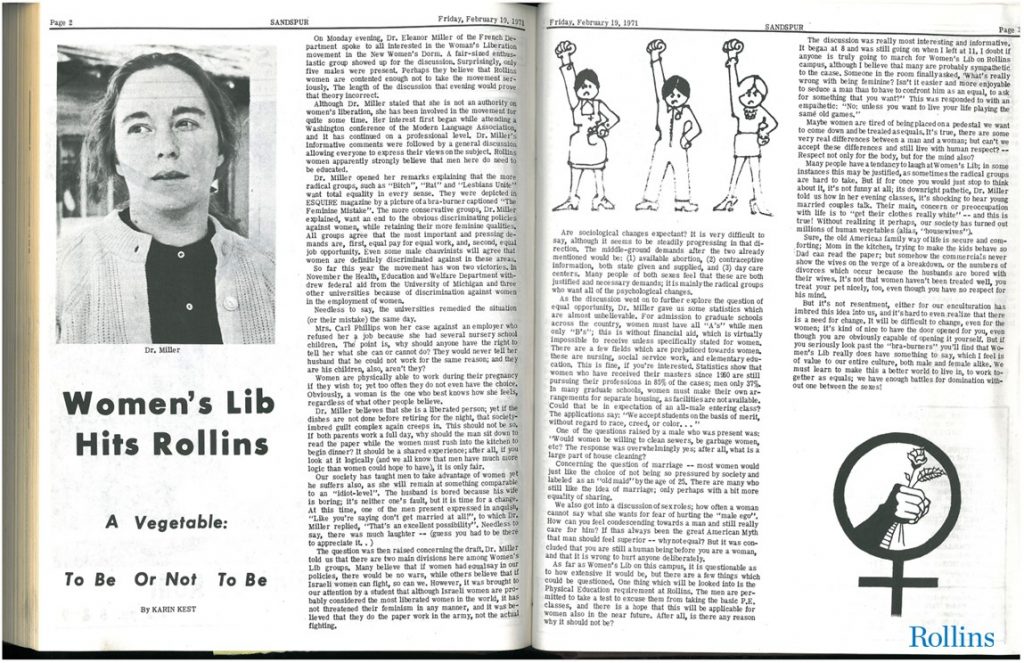

“Women’s Lib Hits Rollins,” published in The Sandspur, February 19, 1971 (Image: Rollins College Archives)

This discussion ushered in the beginning of women’s studies programs at both public and private education institutions. San Diego State University (SDSU), a public school, was the first in the nation to offer a women’s studies program in 1970, and later established a minor in the study in 1975.[7] Only a few years after the start of SDSU’s program, Puget Sound University, a private institution, began their program and established their minor in the same year as SDSU established theirs.[8] Similarly, Denison University, a liberal arts college, established a women’s studies program in 1972 and established their minor later in 1983.[9] By 1985, there were a total of 450 certificate and minor programs available at all types of academic institutions.[10] Although the policies created a financial incentive for public schools to established programs to advance gender equity, they also created a social incentive, feed by the continuance of the women’s movement, for private and liberal arts colleges to establish programs as well.

Rollins College felt the influence of these policies. In 1981, Rollins adopted Affirmative Action policy, demonstrating the diffusion of gender-equity goals into the college.[11] Rollins had a women’s studies program in their Continuing Education School as early as 1974.[12] However, the incorporation of gender-equity policy encouraged the creation of a women’s studies program in the general curriculum in 1981.[13] This process was spearheaded by by Dr. Rosemary Keefe Curb, who came to Rollins in 1979 as an assistant Professor of English with specific interests in twentieth-century African American and women’s literature.[14] In her youth, after hearing the call to religious life, Curb spent eight years as a Dominican nun.[15] She later left the convent in 1968, married, and had a daughter.[16] Divorced just a couple years later, she came out as a lesbian in 1973.[17] She lived as a single mother whilst earning her M.A., and later her Ph.D., in English literature from the University of Arkansas during the height of the women’s movement.[18] Within her first year at Rollins, Curb worked alongside students to found a women’s group called Rollins Organization for Women (ROW).[19] The purpose of the group was to “provide a much-needed opportunity for Rollins women to become aware of the opportunities, challenges, and prejudices which lay before them.”[20] By the end of her second year in 1981, Curb took this one step further and organized a handful of faculty and spearheaded the women’s studies program with the same purposes in mind.[21] Rollins’s adoption of gender-equity policy and the presence of a faculty member with interest in the subject at hand and willing to spearhead the process allowed for the adoption of a women’s studies program.

Dr. Rosemary Keefe Curb, creator of the Women’s Studies Program, taught at Rollins from 1979 to 1993 (Photo: Rollins Magazine, Fall 2012)

As women’s studies programs developed across the country in the early 1980s, they remained closely tied to the women’s movement and thus highly influenced by women’s issues of the time. At the forefront of women’s issues in the 1980s were those under attack by the Reagan administration. As the Reagan administration campaigned for a return to white, Christian Conservativism, polices like women’s reproduction rights were threatened.[22] Despite the rise in anti-feminist political action from the Reagan administration and the Christian right, feminists found it difficult to critique the administration without addressing similar critiques from within their own movement.[23] In 1981, Angela Davis published her book Women, Race and Class, which explained how race had always been a barrier to women’s liberation.[24] In 1984, bell hooks published her book entitled Feminist Theory: From Margin to Center Book, which made the case for why women’s studies should include discussion of ethnicity and race.[25] The publications of critiques such as these and the inability for the women’s movement to address the Reagan era polices without addressing its own discriminatory practice brought race into women’s studies as a category of analysis.

As a result of the critiques risen from within the women’s movement, women’s studies programs began offering courses on women of color. In 1982, Puget Sound held one course titled “African American women in American History.”[26] Lewis and Clark College established their gender studies program in 1985, which addressed specifically addressed race.[27] Slowly across the decade, programs increase their categories of analysis to include race.

Following the national trend, the 1980s marked a slow trickling of diversity into the women’s studies program at Rollins. Curb offered a class in the English department on minority literature as early as 1982, which included black literature and women’s literature.[28] However, as the women’s studies program developed and a course entitled Women Writers emerged, the class on minority literature remained: but with a focus only on Black literature.[29] This shows that race had not yet been adopted as a category of analysis in the curriculum of women’s studies at Rollins. In 1984, Rollins established the women’s studies minor, of which Curb was named coordinator.[30] But despite her scholarly interest in African American literature, and the expansion of courses offered, still no classes on women of color were offered. In 1986, Joan Straumanis was hired as Dean of Faculty.[31] As professor of philosophy and department chair at Denison University, she helped establish one of the first women’s studies programs in the country in 1972.[32] Following her arrival, Rollins’s women’s studies began to add courses on women of color.[33] The presence of a leading woman within women’s studies could have been the encouragement the women’s studies program needed to bring itself more in line with national trends of diversity.

Dr. Joan Straumanis, Dean of the Faculty from 1986 to 1992. (Photo: Rollins College Archives)

Just as national discussions of race revolutionized women’s studies, the HIV and AIDs epidemic of the 1980s and 1990s brought more visibility to gay rights, and with it greater focus on sexuality and gender in society. As the focal point of the HIV/AIDS epidemic of the 1980s and early 1990s, the United States saw an increase of stigma against the gay community which, in turn, spurred activism for gay rights.[34] However, federal policy sought to compromise between activists and the anti-gay conservative right. In 1993, the U.S. military instituted the “Don’t Ask, Don’t Tell” policy, permitting gays to serve but banning homosexual activity.[35] This was followed by the Defense of Marriage Act (DOMA) in 1996, which defined marriage at the federal level as the union of one man to one woman, “barring same-sex married couples from being recognized as ‘spouses’ for the purposes of federal marriage benefits.”[36] As activism increased people’s understanding of the complexities of gender and sexuality during this time, it intensified discussion of those topics within women’s studies.

The increased awareness of LGBTQ issues brought a deeper, more complex discussion of gender and sexuality into the general curriculum of women’s studies. Increased social awareness of LGBTQ issues through literature such as Judith Butler’s The Publication Of Gender Trouble: Feminism And The Subversion Of Identity in 1990 and Ann Fausto-Sterling’s Myths of Gender in 1992, women’s studies programs began to incorporate more discussions of gender into their courses.[37] In 1995, Duke proposed a certificate-granting program or minor in the study of gender and sexualities.[38] At the University of Puget Sound, “The Year of Gender, Sexuality, and Identity” was announced as the school year’s theme for 1996-1997.[39] By the latter half of the decade, gender and sexuality had become bona fide categories of analysis within women’s studies.

In concurrence with the national discussion on gender and sexuality, Rollins began to offer an increasing number of gender focused courses throughout the 1990s. Due to the influence of Curb’s personal experience and research interest, sexuality had been a focus in Rollins’s women’s studies since its beginning. However, thanks to the increased interest of gender in academia, many new faculty members had research interests in gender which enabled Rollins women’s studies to continue to evolve and develop along national trends.[40] In 1991 a class entitled The Body in Society was introduced to the curriculum by Mary McCormack, an Assistant Professor of Sociology hired in 1990.[41] The course offered “an examination of recent discourses that [had] emerged from studies of gender [and] sexuality.”[42] Lynda M. Glennon, Professor of Sociology, taught a class entitled The Family, which offered “an examination of how political, economic, and social changes affect marriage and the family currently and in coming decades.”[43] In the 90s, the focus on sexuality and gender made its way into academia, influencing the interests of new scholars.[44] These new scholars entered colleges, such as Rollins, as new faculty and helped to foster discussions of sexuality and gender in the curriculum. At the turn of the new century, the heightened focus on sexuality and gender would continue to shape the evolution of women’s studies curriculum.[45]

Members of Voices for Women, 2011 (Photo: Rollins College Archives)

Over its first two decades, Rollins College’s women’s studies evolved according to the trends within the women’s movement but was most importantly driven by the extra scholastic interests of its faculty. The establishment came during a women’s studies boom and was initiated by a woman whose personal experiences lead her academic inquiry. During the Reagan era, as the women’s movement was forced to turn inward and address its own whiteness, Rollins too adopted courses on women of color. In the 90s, the focus on sexuality and gender made its way into academia, influencing the interests of new scholars. These new scholars entered colleges, such as Rollins, as new faculty and helped to foster discussions of sexuality and gender in the curriculum. At the turn of the new century, the heightened focus on sexuality and gender would continue to shape the evolution of women’s studies curriculum. [46]

Dr. Michelle Stecker (second from left), the first director of the Lucy Cross Center for Women and Their Allies, with students in 2012. “The Lucy” provides a safe and welcoming space for all members of the Rollins community. (Photo: Rollins College Archives)

[1] Alice E. Ginsberg, “Triumphs, Controversies, and Change: Women’s Studies 1970s to the Twenty-First Century,” in The Evolution of American Women’s Studies: Reflections on Triumphs, Controversies and Change, ed. by Alice E. Ginsberg, (London: Palgrave Macmillan, 2008): 15.

[2] William G. Tierney, “The Parameters of Affirmative Action: Equity and Excellence in the Academy,” American Educational Research Association 67, no. 2 (Summer 1997): 167.

[3] Ginsberg, “Triumphs, Controversies, and Change,” 15.

[4] “Title IX and Sex Discrimination,” U.S. Department of Education, accessed December 12, 2020, https://www2.ed.gov/about/offices/list/ocr/docs/tix_dis.html.

[5] Ginsberg, “Triumphs, Controversies, and Change,” 15.

[6] “Women’s Educational Equity Act,” U.S. Department of Education, accessed December 12, 2020, https://www2.ed.gov/programs/equity/index.html; “Definitions,” U.S. Department of Education, accessed December 12, 2020, https://www.ed.gov/race-top/district-competition/definitions.

[7] “History,” Department of Women’s Studies San Diego State University, accessed December 13th, 2020, https://womensstudies.sdsu.edu/history.htm.

[8] “GQS 201: Introduction to Gender, Queer, and Feminist Studies: Section B Timelines (White),” University of Puget Sound, accessed December 13, 2020, https://research.pugetsound.edu/c.php?g=589147&p=7290117.

[9] “Program History,” Denison University Department of Women’s Studies, accessed December 13, 2020, https://denison.edu/academics/womens-gender-studies/program-history.

[10] Marilyn J. Boxer, When Women Ask the Questions: Creating Women’s Studies in America (Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 1998), 10.

[11] Catalogue, 1981-1982, Rollins College Course Catalogues, Rollins College Scholarship Online, https://scholarship.rollins.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1048&context=catalogs_liberalarts.

[12] Pamphlet for Division of Continuing Education, Rollins College Archives and special Collections, Olin Library, Rollins College, Winter Park, FL.

[13] Catalogue, 1981-1982; Barbara Miller Solomon, In The Company of Educated Women, (New Haven and London: Yale University Press, 1985) 204.

[14] Catalogue, 1979-1981.

[15] Rosemary Curb and Nancy Manhattan, Lesbian Nuns: Breaking Silence (Tallahassee: Naiad Press, 1989), xix-xxiii.

[16] Curb, Lesbian Nuns, xxi.

[17] Curb, Lesbian Nuns, xxii.

[18] Curb, Lesbian Nuns, xxii; Catalogue, 1979-1981.

[19] Aura Bland, “New Group Fights for Life,” Sandspur, May 9, 1980.

[20] “Women’s Movement Meeting,” Sandspur (Winter Park, FL), February 22, 1980; “Women’s Awareness Group Organizes at Rollins,” Sandspur, (Winter Park, FL), March 14, 1980.

[21] Catalogue, 1981-1982.

[22] Françoise Coste,“’Women, Ladies, Girls, Gals…’: Ronald Reagan and the Evolution of Gender Roles in the United States,” Miranda (December 2016) http://journals.openedition.org/miranda/8602.

[23] Boxer, When Women Ask the Questions, 112.

[24] “Timelines,” University of Puget Sound, accessed December 13, 2020, https://research.pugetsound.edu/c.php?g=589147&p=7290117.

[25] “Timelines,” University of Puget Sound, accessed December 13, 2020, https://research.pugetsound.edu/c.php?g=589147&p=7290117.

[26] “Timelines,” University of Puget Sound, accessed December 13, 2020, https://research.pugetsound.edu/c.php?g=589147&p=7290117.

[27] Caryn McTighe Musil, The Courage to Question: Women’s Studies and Student Learning, (Washington, D.C.: Association of American Colleges, 1992), 44.

[28] Catalogue, 1982-1983.

[29] Catalogue, 1981-1982; Catalogue, 1982-1983; Catalogue, 1984-1986.

[30] Catalogue, 1984-1986.

[31] Kathi Rhoads, “Joan Straumanis Looks Ahead,” Sandspur, (Winter Park, FL) October 1, 1986.

[32] “Program History,” Denison University; Kathi Rhoads, “Joan Straumanis Looks ahead.”

[33] Catalogue, 1987-1988; Catalogue, 1988-1989; Catalogue, 1989-1990; Catalogue, 1990-1991.

[34]“A Brief History of Civil Rights in the United States: The HIV/AIDS Epidemic,” Georgetown Law, accessed December 12, 2020, https://guides.ll.georgetown.edu/c.php?g=592919&p=4182199.

[35] “A Brief History of Civil Rights in the United States: The 1990s, “Don’t Ask, Don’t Tell,” and DOMA,” Georgetown Law, accessed December 12, 2020, https://guides.ll.georgetown.edu/c.php?g=592919&p=4182200.

[36] Ibid.

[37] “Timelines,” University of Puget Sound; Bonnie J. Morris, “History of Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual and Transgender Social Movements,” American Psychological Association, accessed December 12th, 2020, https://www.apa.org/pi/lgbt/resources/history.

[38] “Proposal for A Certificate-Granting Program Or Minor In The Study Of Gender And Sexualities,” Duke University, accessed December 12, 2020, http://people.ku.edu/~jyounger/Duke/DukeSXLProgramProposal1995.html.

[39]“Timelines,” University of Puget Sound.

[40] Catalogue, 1990-1991, -2001

[41] Catalogue, 1990-1991.

[42] Catalogue, 1990-1991.

[43] Catalogues 1990-2001.

[44] Catalogues 1990-2001.

[45] Margaret McLaren interviewed by Mickayla Grasse-Stockman, December 11, 2020, recording in possession of author.

[46] Wendy Brandon interviewed by Mickayla Grasse-Stockman, December 14, 2020, recording in possession of author; Ryan Musgrave interviewed by Mickayla Grasse-Stockman, December 11, 2020, notes in possession of author.

1 thought on “The Origins and Evolution of Women’s Studies at Rollins College, 1980-2000”