by Prof. Wenxian Zhang

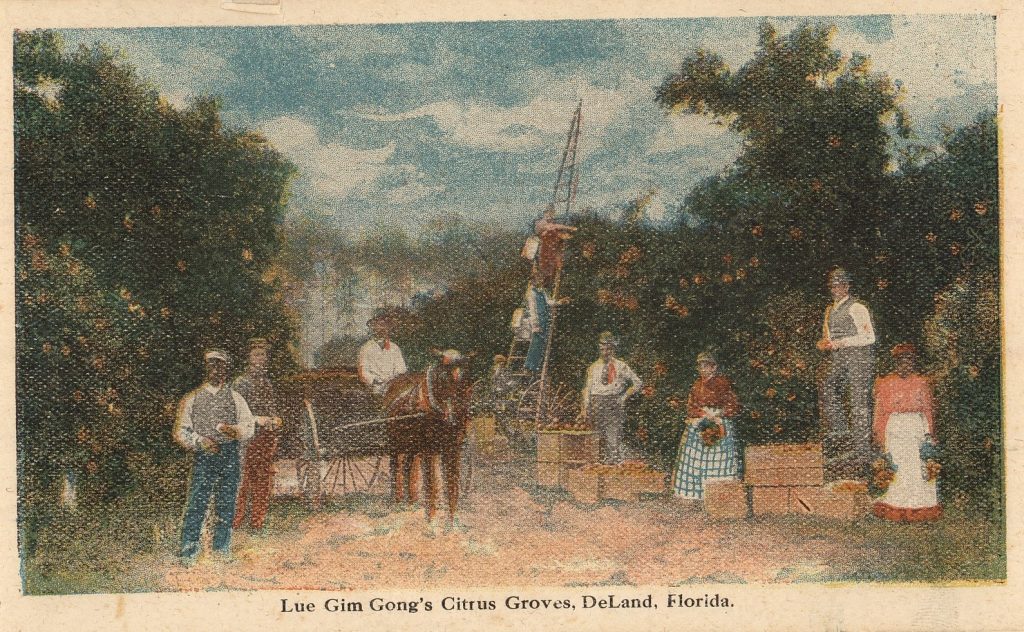

Lue Gim Gong’s Citrus Groves, Deland, Florida, from the stationery of the North Adams National Bank (Image: Courtesy of Special Collections at the University of South Florida Libraries)

“No one should live in this world for himself alone, but to do good for those who come after him.”

The Archives is pleased to share this post in celebration of Asian Pacific American Heritage Month, as our nation pays tribute to the contributions and achievements of Asian Americans and Pacific Islanders in the United States. If you would like to support Lue’s induction to the Florida Citrus Hall of Fame, please see here for nomination information.

*****

Lue Gim Gong (刘锦浓, August 24, 1857 – June 3, 1925), a Chinese American immigrant in the late nineteenth century, was an accomplished horticulturalist who contributed to the growth of the American citrus industry by developing a cold-resistant orange and other plants. In 2000, Lue was recognized as a “Great Floridian” by the Florida Department of State for his significant contributions to the Sunshine State (Dickinson, 2018). Overcoming hardship, ignorance and injustice, Lue lived a triumphant life that continues to inspire generations of people in our multicultural society in the twenty-first century.

Lue Gim Gong was born in the village of Lung On in the Taishan (Toishan) district of China (McCunn, 1989). At age fifteen and led by his uncle, he left his home in Guangdong Province, and immigrated to the United States (Calkins, 1991). After a dreadful voyage over the Pacific Ocean that lasted for weeks, he landed on the West Coast on June 27, 1872 and began to work in a shoe factory in San Francisco. Shortly after, he joined seventy-four other Chinese workers hired by Calvin T. Sampson to break a strike at his North Adams shoe factory in Massachusetts. There he learned English at a Chinese Sunday School, joined the Baptist Church and became a Christian, and met Fannie Burlingame (1828-1903), a volunteer teacher at the school who greatly influenced his life. She was intrigued by the fresh and eager intelligence of young Lue, and invited him to live in her house. Through her caring efforts, Lue soon became a member of the family and began to call her “Mother Fannie.” He spent much time working in Burlingame’s large garden and greenhouse filled with exotic vegetation. He was familiar with plants since he had worked in the orange groves in Lung On, where his mother had taught him how to cross-pollinate blossoms and graft stock.

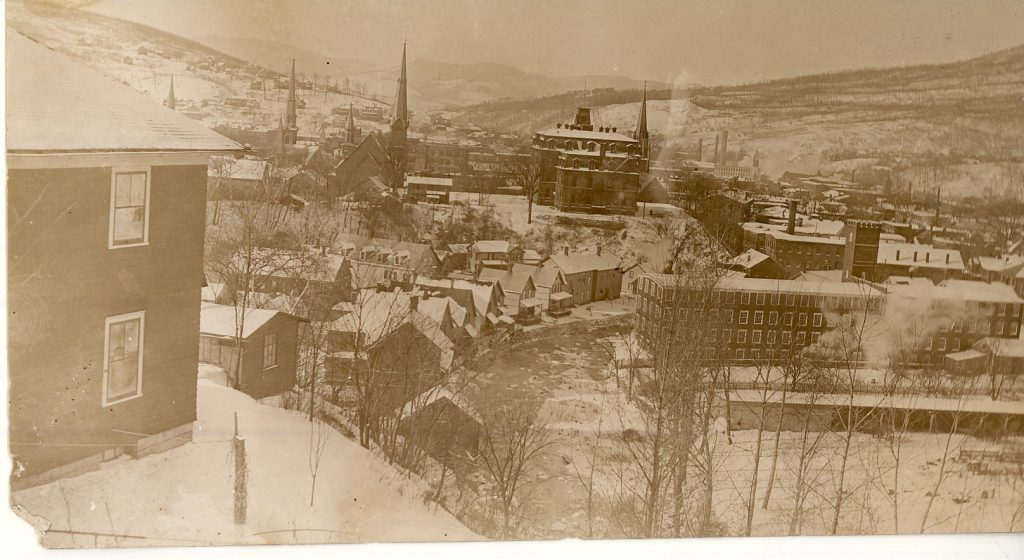

North Adams, Massachusetts, a mill town in New England, became a center in shoe manufacturing in the nineteenth century (Photo: Courtesy of the University of South Florida Libraries)

In the mid-1880s, Lue was diagnosed with tuberculosis, and was given one year to live if he did not leave the harsh Massachusetts climate. He chose to return to his family in subtropical Guangdong. However, after returning to China, he found that his Christian ideas were no longer completely compatible with the Chinese customs. Furthermore, his family had arranged a marriage that he refused to accept. For his act that brought shame to his family, Lue’s name was stricken from the clan genealogy (McCunn, 122). The four-month homecoming had become an unhappy journey, and he was eager to go back to the States, even though that meant his life might be shortened there. The arrangement turned out to be a difficult task, as the Chinese Exclusion Act of 1882 was already in effect. Miss Burlingame had to forge the documents that listed him as a merchant who planned to open a store in Massachusetts (McCunn, 122).

Lue Gim Gong on a horse wagon with Fannie Burlingame in DeLand, Florida, with two African American workers in background (Photo: Courtesy of the University of South Florida Libraries)

Selecting ripe fruits from Lue Gim Gong’s citrus grove in DeLand, Florida, in March 1894. Lue is sitting on the horse wagon third from left; Fannie Burlingame is standing third from right. Several African American laborers were visible on both sides of the photo and on the ladder. Within a year, severe freezes had destroyed most orange trees in Central Florida and devasted the state’s agricultural economy. (Photo: Courtesy of the University of South Florida Libraries)

In DeLand, Florida, Lue Gim Gong with his horses standing on the far right, Fannie Burlingame was also standing on the right next to the horses. (Photo: Courtesy of the Florida State Archives)

Lue returned to the United States in December 1886 and went directly to Florida, where he stayed with the Burlingame family on their newly purchased orange groves in DeLand. The following year, he became an American citizen and cast his first vote in a general election. The severe freezes in the 1890s greatly motivated him to work on developing a strain of orange that would resist frost. He crossed the Florida Harts Late orange with a variety from the Mediterranean region. The result was a sweet, juicy fruit that could endure severe weather. It was named the Lue Gim Gong Orange and was propagated by Mr. George Tabor of the Glen St. Mary’s Nursery. Hume (1926) noted in his Cultivation of Citrus Fruits that “this hardy thrifty-growing variety is very resistant to cold; in fact, it may be the hardiest of all sweet orange varieties now commonly cultivated in America. It is a noteworthy fruit because of the length of time the fruit may be held on the tree.” The New York Times (1925) reported that “he [Lue] saved the industry millions of dollars by his perfection of an orange tree on which fruit would remain until far beyond maturity.” For this achievement, the American Pomological Society awarded Lue a Silver Wilder Medal in 1911, the first time such an award was made for citrus (Calkins, 28; Henry A. DeLand House Museum, 2002).

The Silver Wilder Medal from the American Pomological Society, 1911 (Image: Courtesy of the University of South Florida Libraries)

During the following years, Lue also developed an aromatic grapefruit, and propagated roses and other flowers and fruits. For his contribution to Florida’s citrus industry, Lue was called “the wizard of citrus growers,” and “the Chinese Burbank of Florida.” However, his success with the orange and other botanical discoveries only brought him fame, not fortune. As his name spread, numerous visitors came to his grove, and he would give away free samples of his fruit and plants. Not a very talented businessman, he was often cheated by his distributors, who refused to pay for materials they ordered and royalties he was entitled to. In 1922, when his mortgage was due and Lue had no money to pay his bills, the Florida Grower published his story, and the magazine readers, along with citizens of DeLand and North Adams, responded to raise sufficient funds to save his property. Never married, Lue spent his last years alone in his beloved grove, accompanied only by his horses, named Baby and Fannie, and pet rooster, March.

Lue Gim Gong with his pet rooster March in DeLand, Florida (Photo: Courtesy of the Florida State Archives)

Lue Gim Gong died on June 3, 1925, and was buried in the Oakdale Cemetery in DeLand, Florida. Hundreds of people attended his funeral, and newspapers published obituaries that praised his horticultural achievements. His accomplishment was also featured prominently in the Florida Pavilion at the 1933 Chicago World’s Fair. However, over time, scarce articles were written on Lue, and his story was generally forgotten. The scholarly research and creative work of Ruthanne Lum McCunn has generated a renewed interest about Lue during recent years. Her book Chinese American Portraits: Personal Histories 1828-1988 was selected by Choice magazine as an Outstanding Academic Book in 1990. Her second novel, Wooden Fish Songs, which won the Jeanne Farr McDonnell Award for Best Fiction in 1997, vividly portrayed Lue’s remarkable life and hard times in two cultures, his loneliness, fear, and brave insistence on survival. A successful stage adaptation of the book has also toured over dozens of colleges, libraries, museums, and community organizations, including the Smithsonian. Besides McCunn’s Work, two other notable books were also written about Lue: The Plant Wizard: The Life of Lue Gim Gong by Murian Murray in 1970, and The Gift of the Unicorn: The Story of Lue Gim Gong, Florida’s Citrus Wizard by Virginia Aronson in 2002.

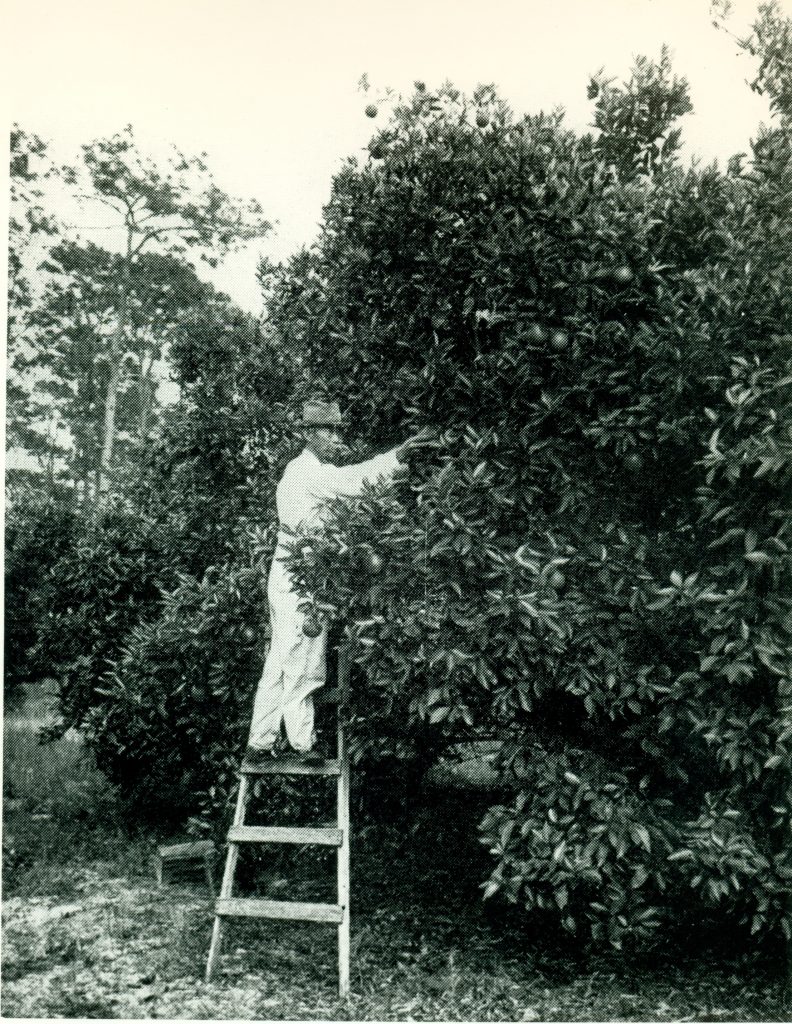

Lue Gim Gong working in his citrus grove in DeLand, FL (Photo: Courtesy of the Florida State Archives)

Today, the only monument honoring Lue Gim Gong is located at 137 West Michigan Avenue in DeLand, Florida. Soon after his death in 1925, people from the local community who knew him and were impressed by his works planned to erect a bust in his memory, but the Florida land boom was soon busted, and the local economy was also devastated by the ensuing Great Depression, so the idea was gradually forgotten. It has taken seventy-four years to finally honor Lue’s legacy and his contributions to the state’s citrus industry. The Lue Gim Gong Memorial Garden in DeLand was dedicated on October 15, 1999. Along with the sculpture and his orange trees, there is a pavilion similar to his gazebo in the citrus grove where Lue held prayer services every Sunday morning. The location is also the home of the West Volusia Historical Society, where research materials about Lue are kept. The Society maintains both primary and secondary source files on Lue throughout the years, and a finding aid is available. Folders include a biography of Lue Gim Gong; information about North Adams, Massachusetts; Sampson’s “Chinese experiment”; and the Burlingame family; information about his orange and other citrus experiments; information about his funeral and memorial; letters, inquires, newspaper articles, photos, and so on. Besides the West Volusia Historical Society, additional information can also be found in the North Adams Historical Society and the North Adams Public Library in Massachusetts, the Florida Memory Project at the State Library & Archives of Florida, and the Special Collections at the University of South Florida Libraries. In May 2024, Lue’s life was featured in a Spectrum Ch. 13 news story.

Lue Gim Gong holding his pet rooster, March, posed with a group of visitors to his citrus grove in DeLand, FL (Photo: Courtesy of the University of South Florida Libraries)

References:

Calkins, Virginia (1991). The Gardens of Lue Gim Gong. Cobblestone: The History Magazine for Young People 12(3), 26-28.

Chinese Fruit Wizard Dies (1925, June 5). The New York Times, 17:5.

Dickinson, Joy Wallace (2018). “Citrus Wizard” Merits Place in Hall of Fame. Orlando Sentinel, https://www.orlandosentinel.com/features/os-joy-wallace-dickinson-0930-story.html (30 September 2018).

Henry A. DeLand House Museum (2002). Lue Gim Gong the “Citrus Wizard.” http://www.delandhouse.freeservers.com/gazebo.htm (30 April 2021).

Hume, Harold (1926). The Cultivation of Citrus Fruits. New York: Macmillan. 65.

Lue Gim Gong Honored by Savants: Gentle Chinese in Florida Won Medal for New Orange – A Master in His Field (1925, June 21). The New York Times, xx18.

McCunn, Ruthanne Lum (1989). Lue Gim Gong: A Life Reclaimed. Chinese America: History and Perspectives 3, 117-135.

West Volusia Historical Society (1999). Lue Gim Gong: The Citrus Wizard 1860 – 1925. DeLand, Florida.