by Erika Wesch ’23

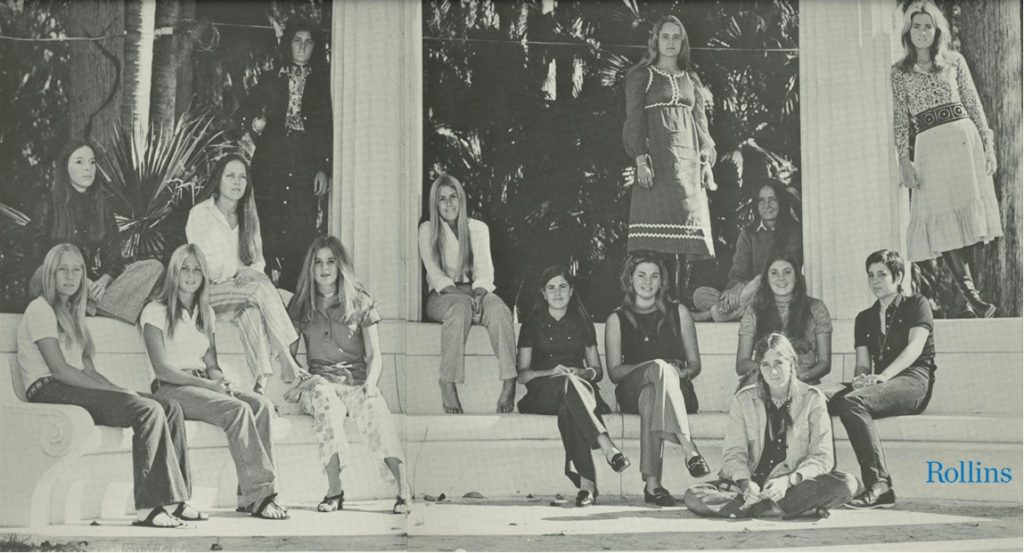

Members of Non Compis Mentis, from the 1971 Tomokan yearbook (Photo: Rollins College Archives)

In celebration of women’s history, we are pleased to present the third in a series of blog posts written by students in Prof. Claire Strom’s Fall 2020 class, Researching American History. The Archives staff is grateful to Prof. Strom and her students for sharing their work with us.

*****

In the southern United States, sorority culture and college life often go hand in hand. At Rollins College in Winter Park, Florida, the school of less than 3,000 undergraduates has eight sororities on campus, each appealing to different types of incoming women.[1] While seven of these are associated with a national organization, one, Non Compis Mentis, can only be found on the Rollins campus. Non Compis Mentis, or NCM, is a local sorority founded at Rollins in the fall of 1970. While they are active members in the Panhellenic Council, or the governing body of all sororities on Rollins’ campus, NCM sisters pride themselves on being founded on values that contrast typical sorority stereotypes.[2] Founded during a time of demographic changes and disillusionment, NCM challenges traditional sorority structures and values.

The collegiate atmosphere at the start of the 1970s reversed the social revolution of the 1960s, providing a place for NCM to revive the resistance. The radicalism of the 1960s in the United States revolutionized the college campus, making it a place of protests and activism.[3] As students began to enter college in the 1970s, there was a “striking contrast between the 1960s and the 1970s. Like students in the 1950s, those of the 1970s had, to a significant degree, returned to ‘privatism’.”[4] Overall, students “were committed to family, leisure, and career, but ‘oblivious to broader social or ideological interests.’”[5] This switch decreased the amount of unity on college campuses and emphasized performance over social connections, often leaving students “disappointed, disillusioned, drained and exhausted’.”[6] These national trends grazed Rollins’ campus, sparking reactions.

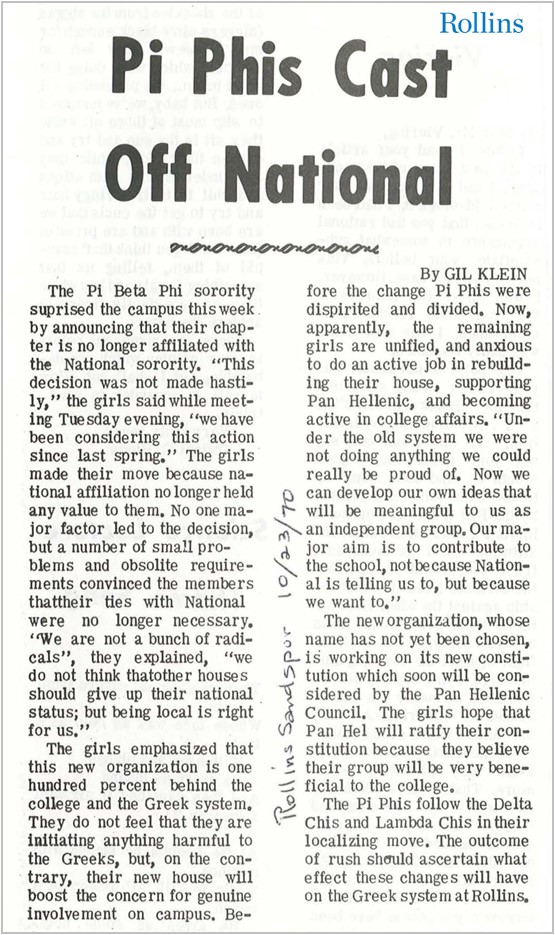

Inspired by the movements before them and worried about the trends of the 1970s, the women of Rollins’ chapter of Pi Beta Phi founded NCM on the tail end of the radical 1960s. Feeling “dispirited and divided” at the beginning of the 1970-71 school year, the national sorority Pi Beta Phi decided to disaffiliate with their national organization.[7] At their meeting, the women of Pi Beta Phi “demonstra[ted] an emtion [sic] that seem[ed] to be dying out at Rollins — high-pitched enthusiasm,” showing how their switch to local hoped to inspire a new culture of “genuine concern for the problems and activities of Rollins College.”[8] After intense discussion, NCM was approved by the Panhellenic Council in November of 1970 on a provisional basis.[9] While they did not denounce the other sororities on campus, the new NCM women claimed “under the old system [they] were not doing anything [they] could really be proud of.”[10] The new women wanted to create a culture of individuals proud to be individuals, something they felt they did not have under Pi Beta Phi restrictions.[11]

Pi Beta Phi sorority dissolves its affiliation with its national organization, as reported by The Sandspur in October 1970 (Image: Rollins College Archives)

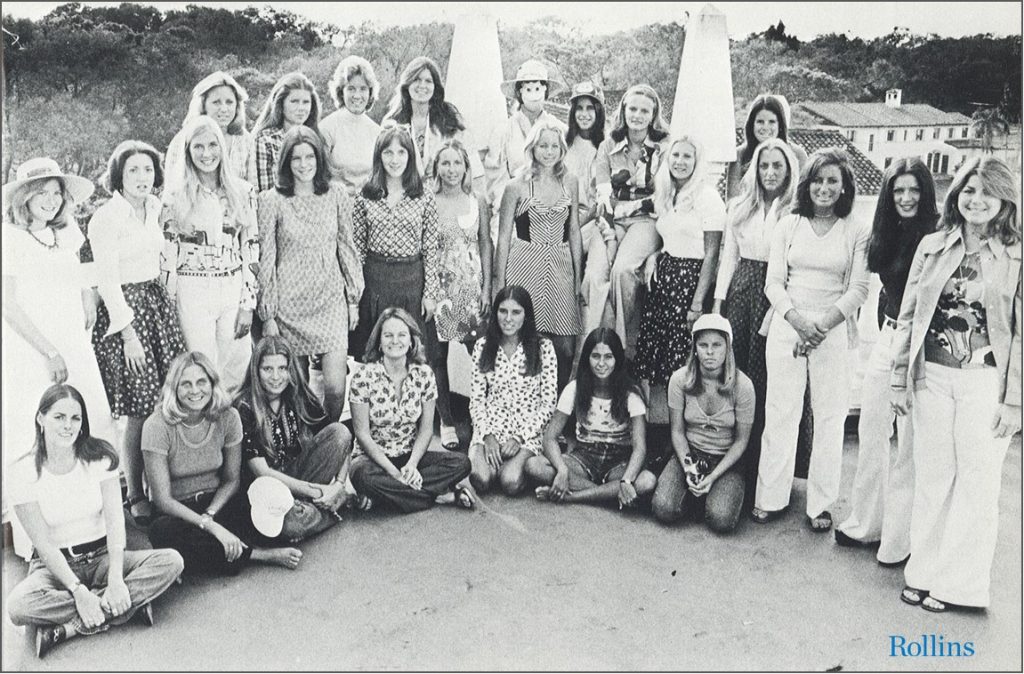

By emphasizing individualism, NCM contrasted the conformity of traditional sororities. Pledging to a sorority or fraternity often places underclassmen into “comfortable,” “homogeneous,” and “protective” communities, resulting in members who are all the same, or new pledges having a “petrifying” desire “to fit in.”[12] The original members of NCM, however, prided themselves on their individuality.[13] In the official constitution, their mission statement advocates for “an unconditional family environment that promotes individuality,” and the sisters and alumni actively live up to this value.[14] Their fundraising and charity reflect their values as well. While national organizations have a specific charity each chapter has to fundraise for, NCM has the flexibility to follow the passions of its members.[15] Often, this includes local Winter Park and Orange County organizations, such as their choice organization in 1999, A Gift for Teaching, a local organization that donates free school supplies for teachers in the Orlando area.[16] The events they chose also reflected this individuality. In 1972, NCM hosted an “All-Campus Auction,” where students and faculty auctioned goods and services off to the highest bidder.[17] The campus was abuzz, and the school newspaper featured a comic remarking how “all the fellows on the Rollins College Campus are talking about the NCM Auction [sic]… pretty neat huh?”[18] The auction was an untraditional form of raising money for the campus’s Chapel Fund, inviting participation from the whole campus.[19] The values and actions of NCM differentiated them from the other national sororities on campus, showing their commitment to individuality and nonconformity.

Without a national connection, NCM was able to reduce the strict limitations of their sister organizations. At the writing of their constitution, the founders advocated for limited structure in their organization. In a collection of notes on the newly drafted NCM constitution, a woman questioned a policy, writing “isn’t this against the original NC’M [sic] plans to be free of structure?”[20] The original members had few required meetings or hierarchy, truly emphasizing social connection over tradition.[21] Traditional national sororities are restricted by required national rules and regulations, intense fines, rituals, and chapter meetings, aspects NCM minimized in their organization.[22]

Members of NCM, from the 1975 Tomokan yearbook (Photo: Rollins College Archives)

NCM also mitigates the financial responsibility of its sisters, inviting more economically diverse members. For traditional national sororities, “the financial commitment a sister must make to her sorority can be enormous.”[23] Initiation and national fees, dues, fines, and “social expenses” are all expected to be paid out of pocket by sorority members, and an average student can “expect to spend $30,000-$35,000 on the Greek experience” over five years.[24] Therefore, sororities and fraternities “disproportionately [attract], and [court], middle- and upper-class undergraduates.”[25] Being local, NCM eliminates any national fees, and tries to keep their dues as low as possible.[26] By reducing the financial commitment, NCM is able to break the classism of traditional Greek life and provide opportunities for other women who would normally avoid sororities.

Today, NCM continues its tradition-breaking by reducing gender and social restrictions. As a progressive organization, NCM has been a leader in providing spaces in sororities for those who identify as non-binary. Non-binary people do not necessarily identify as male or female, and there have been questions on how they fit into the binary Greek system that emphasizes brotherhood and sisterhood.[27] Various sororities, including NCM, have taken steps to amend their constitutions to include those who “want to be in them.”[28] Annually, NCM holds a chapter-wide meeting to amend their constitution, allowing sisters to propose changes as the values of the members evolve.[29]

In the 2010s, NCM even considered leaving the Greek community because they felt it did not align with their vision for the sorority. To avoid Panhellenic restrictions from Rollins and “[symbolize] another large psychological step away from tradition,” the women of NCM debated becoming a service organization like Rollins’ Pinehurst Organization.[30] Pinehurst’s members live together and have their own community, but without the requirements of the Panhellenic Council that did not align with NCM’s value of individuality.[31] The sisters who wanted to remain a sorority, as well as various alumni, voted against the decision to disassociate, but the debate still remains contentious within the sorority.[32]

Fifty years later, NCM still embodies individuality and independence on Rollins’ campus. While national Greek organizations are fighting against their stigma of being “classist, exclusionary groups,” NCM has no problem following the rules it set for itself at its founding.[33] Reacting to the radicalism of the 1960s and rising passivism in the 1970s, NCM established itself on principles of individuality, inclusion, and freedom, avoiding the restrictions of national organizations as a local sorority. Their uniqueness continues to impact Rollins and provide a model of inclusion for Greek life across the South.

NCM members on Bid Day, 2017 (Photo by Scott Cook)

*****

[1] “Fraternity & Sorority Life,” Rollins College, accessed December 18, 2020. https://www.rollins.edu/fraternity-sorority-life/

[2] “Fraternity & Sorority Life,” Rollins College.

[3] Helen Lefkowitz Horowitz, Campus Life: Undergraduate Cultures from the End of the Eighteenth Century to the Present (New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 1987) 250.

[4] Helen Lefkowitz Horowitz, Campus Life, 251.

[5] Helen Lefkowitz Horowitz, Campus Life, 251.

[6] Helen Lefkowitz Horowitz, Campus Life, 250.

[7] Gil Klein, “Pi Phis Cast Off National,” The Rollins Sandspur, Winter Park, FL, 23 Oct 1970.

[8] G. K., “A Unique Experience,” The Rollins Sandspur, Winter Park, FL, 23 Oct 1970.

[9] Anonymous, “Pan Hell Approves N.C.M.,” The Rollins Sandspur, Winter Park, FL, 6 Nov 1970.

[10] Gil Klein, “Pi Phis Cast Off National.”

[11] Cathy Susko, NCM Pledge Class 1972, interviewed by author, 5 Dec 2020, recording and notes in possession of the author.

[12] Alan D. DeSantis, Inside Greek U.: Fraternities, Sororities, and the Pursuit of Pleasure, Power, and Prestige (Lexington: The University Press of Kentucky, 2007) 21; Alexandra Robbins, Pledged: The Secret Life of Sororities (New York: Hyperion, 2004) 37.

[13] Cathy Susko, NCM Pledge Class 1972, interviewed by author.

[14] Micaela Castro, NCM Pledge Class 2015, interviewed by author, 29 November 2020, notes in possession of the author; Alice Habib, NCM Pledge Class 2016, interviewed by author, 29 November 2020, notes in possession of the author; Cathy Susko, NCM Pledge Class 1972, interviewed by author.

[15] Micaela Castro, NCM Pledge Class 2015, interviewed by author; Alice Habib, NCM Pledge Class 2016, interviewed by author.

[16] Nicole Hilberth, “NCM Drive,” The Rollins Sandspur, Winter Park, FL, 29 April 1999.

[17] Gail E. Johnson, Memo to Administration and Faculty from NCM, 1972, Non Compis Mentis Collection, Rollins College Archives and Special Collections, Olin Library, Rollins College, Winter Park, Florida (hereafter RCASC).

[18] Anonymous, Cartoon, The Rollins Sandspur, Winter Park, FL, 6 March 1972.

[19] Gail E. Johnson, Memo to Administration and Faculty from NCM, 1972.

[20] “Remarks on the N.C.M. Constitution,” 8 Feb 1971, Non Compis Mentis Collection, Rollins College Archives and Special Collections, Olin Library, Rollins College, Winter Park, Florida, RCASC.

[21] Cathy Susko, NCM Pledge Class 1972, interviewed by author.

[22] Alexandra Robbins, Pledged: The Secret Life of Sororities, 85-87.

[23] Alexandra Robbins, Pledged: The Secret Life of Sororities, 68; KJ Dell’Antonia, “Sororities: Sisterhood, With More Than One Price Tag,” The New York Times, 30 Oct 2014.

[24] Alan D. DeSantis, Inside Greek U., 239.

[25] Alan D. DeSantis, Inside Greek U., 239.

[26] Cathy Susko, NCM Pledge Class 1972, interviewed by author.

[27] Sean Callan and Manley Burke, “Non-binary Gender in a Binary System,” Fraternal Law Newsletter, November 2017.

[28] Marco Allen, “Local sororities amend constitutions to include non-binary people,” The Dartmouth, Hanover, New Hampshire, 3 July 2020.

[29] Micaela Castro, NCM Pledge Class 2015, interviewed by author.

[30] Paula Giddings, In Search of Sisterhood: Delta Sigma Theta and the Challenge of the Black Sorority Movement (United States: HarperCollins, 1988) 290; Alexis Neu, “N.C.M. Divided,” The Rollins Sandspur, Winter Park, FL, 19 March 2010.

[31] Micaela Castro, NCM Pledge Class 2015, interviewed by author; Alice Habib, NCM Pledge Class 2016, interviewed by author.

[32] Micaela Castro, NCM Pledge Class 2015, interviewed by author.

[33] Jessica Bennet, “When a Feminist Pledges a Sorority,” New York Times, 9 April 2016.