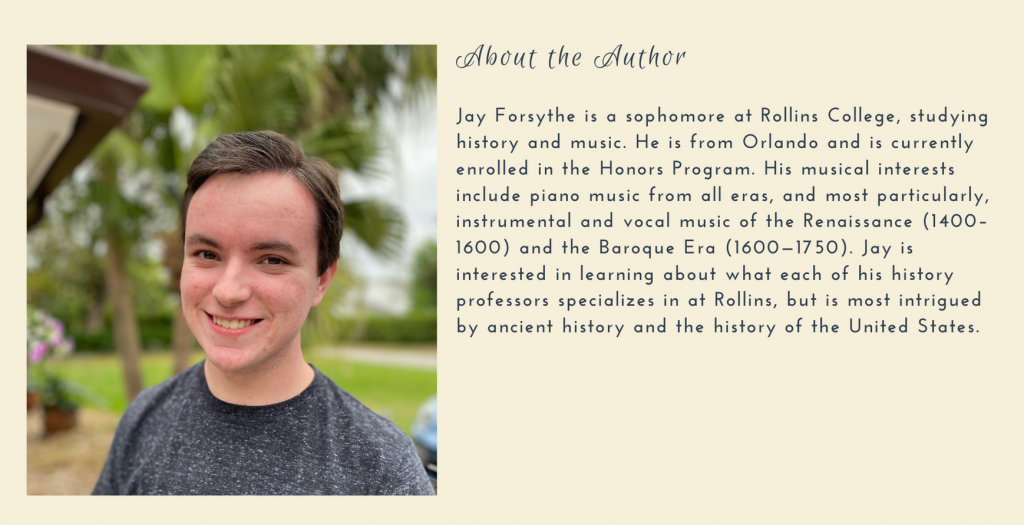

by Jay Forsythe ’23

Bach Festival performers at Knowles Memorial Chapel, 1937 (Photo: Rollins College Archives)

In celebration of women’s history, we are pleased to present the second in a series of blog posts written by students in Prof. Claire Strom’s Fall 2020 class, Researching American History. The Archives staff is grateful to Prof. Strom and her students for sharing their work with us.

For additional information on Mrs. Isabelle Sprague-Smith and the history of the Bach Festival Society, please see Records of the Bach Festival Society.

*****

In 1935, a small group of musicians performed Bach’s Mass in B minor in the Knowles Memorial Chapel at Rollins College.[1] This event marked the first performance of the Bach Festival Society of Winter Park, a project which continues to this day. The road from its first evening to its current established position as part of the cultural heritage of Central Florida, however, was not inevitable, and the festival’s success was only possible through the dedication and hard work of many musicians and administrators. The women involved in the society’s founding were particularly important, though their story is often untold. Despite women’s roles in music being historically limited to domestic performance for familial entertainment, these women were able to become the driving factor behind the Bach Festival’s success, both as leaders and as musicians.[2] Since its inception, the leadership and musical skills of specific women at and around Rollins College have been instrumental to the founding and continuity of the Bach Festival Society of Winter Park.

Situated in Winter Park, Florida, the Bach Festival Society is an organization that presents classical music to the Central Florida area. It consists of an orchestra and volunteer choir, including Rollins students, performing works by Johann Sebastian Bach and other composers every academic year in the Knowles Memorial Chapel at Rollins College for a paid audience. The festival is loosely based on the Bethlehem Bach Choir in Bethlehem, Pennsylvania, which gave its first performance in 1900.[3] At Rollins, an evening performance of Bach’s works in 1935 prompted a committee to form a similar organization the following year.[4] This committee included, among others, Knowles Memorial Chapel Dean Charles Atwood Campbell and several women in the Winter Park area.[5] Chief among them were Isabelle Sprague-Smith and Frances Knowles Warren.

Honorary degree recipients Isabelle Sprague-Smith (left) and Marjorie Kinnan Rawlings (right) with President Hamilton Holt, 1939 (Photo: Rollins College Archives)

Isabelle Sprague-Smith’s contributions of leadership and guidance founded the Bach Festival and kept it afloat. Sprague-Smith was a New York educator and philanthropist, initially active in France and in upstate New York.[6] Her activities included administration and teaching at the Veltin School for Girls in Manhattan, and helping her husband run the People’s Institute, a Progressive Movement initiative to educate new immigrants to New York City about civics.[7] Her membership of the Cosmopolitan Club, a women’s club in New York, also prepared Sprague-Smith for her role in the Bach Festival.[8] Women’s clubs were an early way for women to exercise leadership, and they often focused on promoting cultural education as a form of philanthropy.[9] When Sprague-Smith turned her attention to Winter Park, she effectively founded the Bach Festival Society by writing its charter.[10] She also played an active role in its continuation, from writing college presidents in Florida to solicit their students to come see the festival free of charge, to convincing a dean at Rollins to add it to the students’ academic calendar.[11] Additionally, Sprague-Smith also extensively contacted potential patrons to sell tickets and organized a radio broadcast of the festival in the hopes of bringing it to a nationwide audience.[12] These contributions all brought in a larger audience to Bach performances. However, Sprague-Smith’s contributions notwithstanding, the Bach Festival would not have been possible without its chief venue, the Knowles Memorial Chapel. This building’s very existence at Rollins is thanks to the contribution of another important woman.

Frances Knowles Warren ’35H (Photo: Rollins College Archives)

Frances Knowles Warren was an extensive donor to the college, who gave the venue of the Knowles Memorial Chapel, and the reverent tone it provides, to the Bach Festival. The chapel was donated by Warren in 1932 in memory of her father, Francis Bangs Knowles, one of the founders of Rollins.[13] Warren apparently viewed the building as her personal project; her portrait, located in its hallways, depicts her seated in front of an idealized rendition of the chapel, signaling that it was an important part of her identity and legacy at Rollins.[14] Accordingly, she had strict wishes about the integrity of the chapel, and intended it to be used only for meditative activity among the student body that would lead to their personal spiritual enrichment.[15] Presentation of the works of Bach qualified for this purpose in her eyes, and Warren, on the founding committee of the Bach Festival, volunteered the chapel to be used for its performances.[16] Although she only donated ten dollars to the festival itself, just enough to buy a ticket for a season, her guidance in the administration of the chapel was priceless.[17] Warren’s concerns about the reputation and sanctity of her chapel echoed throughout the early years of the society. For example, do young students at Rollins have the maturity to sing Bach’s religious works in the chapel?[18] Are public broadcasts salient to the spiritual setting of the building?[19] In both cases, Warren provided an important tempering influence. This influence is also reflected in the festival’s early policy of calling “tickets” by the more dignified name of “sponsorships,” another one of Warren’s ideas.[20] The reverent mood established early on by Frances Knowles Warren allowed the Bach Festival to stand on its own musical merits and not spiral into commercialization. These musical merits included contributions by Isabelle Sprague-Smith and other women in Winter Park.

Sprague-Smith had, or quickly acquired, the musical expertise necessary to manage a project like the Bach Festival. Her musical knowledge of Bach’s works and their context complemented her leadership ability. Sprague-Smith collected numerous essays on and translations of Bach’s works intended for her own personal usage, indicating that she felt the need to understand the musical activities of the Bach Festival more closely, and that she had the capacity to study it effectively.[21] She also corresponded with the Swiss theologian and Bach scholar Albert Schweitzer in an attempt to convince him to come to Winter Park and perhaps give a lecture.[22] This correspondence with Schweitzer, who wrote an encyclopedia of Bach’s life and music, is evidence that Sprague-Smith understood the intended philosophy of this music, much of which was written for services at the church where Bach served as concertmaster.[23] Without this knowledge of Bach’s music and personality, Sprague-Smith would not have been as well equipped to run the Bach Festival. However, this music would forever remain mere notes on a page without musicians to bring it alive.

Other women, contributing their skill in teaching, performing, and accompanying, were instrumental in keeping the Bach Festival alive. Historically, women have been encouraged to participate in music, but only as a domestic exercise. Traditional attitudes praise women when able to perform small works, but impose restrictions when they rise to a level to present “competition in a field in which man had so far reigned supreme.”[24] However, the female musicians in the Bach Festival participated above this station in life and helped to sustain a musical organization that has impacted many in Winter Park today. One such woman was Mary Louise Leonard, director of the Rollins Conservatory in the thirties and the founder of a symphony orchestra in Winter Park.[25] Although she did not play a major role later in the history of the Bach Festival itself, she was included in early discussions about it, and the conservatory students she oversaw would have participated in its choir.[26] Female performers included soloists Dorothy Baker and Lydia Summers, who would have worked closely with the conductor to create musical interpretations of the B minor Mass, as well as the numerous women participating in the choir and orchestra.[27] Finally, Katherine Carlo was a piano accompanist in Winter Park who assisted in Bach rehearsals in the forties and fifties in order to prepare the choir to sing in time with the orchestra.[28] Although these women did not have titles or administrative positions within the organization, they were the silent movers of the Bach Festival with their work and carried much responsibility for its success.

Prof. Katherine Carlo (seated at the piano) with fellow members of the Carlo Trio: her husband, Prof. Alphonse Carlo (standing in the middle) and Prof. Rudolph Fischer (seated on the right) (Photo: Rollins College Archives)

The Bach Festival Society of Winter Park’s impact on Winter Park continues to this year, their eighty-fifth since 1935. It is thanks in no small part to the efforts of these women that it continues to provide classical music to the Rollins College area. Within the circle of the society, they are remembered for their leadership and ability. Legend has it that Isabelle Sprague-Smith had the frugal idea to install thumbtacks on an upright piano to simulate the sound of the harpsichord, an eighteenth-century keyboard instrument with a tin-like sound.[29] Although this is apocryphal, it demonstrates her lasting reputation as the founder and proponent of the festival, and the time is past due for Sprague-Smith and her fellow women in the Bach Festival to receive a place in the history of Rollins College.

The Bach Festival Orchestra and Choir, conducted by Prof. John Sinclair (Photo: Rollins College Archives)

*****

[1] “Bach Festival Society 1936-1981,” n.d. (circa 1981), Warren, Frances Knowles: Bach Festival, Warren, Frances Knowles, Trustee Files, Rollins College Archives and Special Collections (hereafter cited as RCASC).

[2] Gavin James Campbell, “Classical Music and the Politics of Gender in America, 1900- 1925,” American Music, Vol. 21, No. 4 (Winter, 2003): 450.

[3] “Steps in the Incorporation of the Bach Festival Organization,” n.d. (circa 1940), Bach Festival 1936-1943, Bach Festival 1936-1992 (hereafter cited as BFS 1936-92), Records of the Bach Festival Society, Bach Festival, Music Programs, RCASC; Raymond Walters, “Bach at Bethlehem, Pennsylvania,” The Musical Quarterly, Vol. 21, No. 2 (April, 1935): 186.

[4] “Bach Festival Society 1936-1981,” n.d., Warren, Frances Knowles: Bach Festival, Warren, Frances Knowles, Trustee Files, RCASC.

[5] “Coming Festival,” Orlando Sentinel, March 27, 1937; Report for the Year 1935-1936, n.d. (circa 1939), Record of the Bach Festival Society of Winter Park 1935-45, BFS 1936-92.

[6] “Memoranda in the Life of Isabelle Dwight Sprague-Smith,” January 10, 1939, Sprague-Smith, Isabelle, Honorary Degrees, RCASC.

[7] Ibid; “People’s Institute Records,” Archives and Manuscripts, New York Public Library, http://archives.nypl.org/mss/2380.

[8] John William Leonard, “Woman’s Who’s Who of America,” (New York: The American Commonwealth Co., 1915): 772.

[9] Barbara Miller Solomon, “In the Company of Educated Women: A History of Women and Higher Education in America,” (Yale University Press, 1985): 123.

[10] “Minutes of the First Meeting for Incorporation of the Bach Festival Organization,” April 6, 1940, Bach Festival 1936-1943, BFS 1936-92.

[11] Memo to Florida college presidents from Isabelle Sprague-Smith on behalf of the Trustees of the Bach Festival Society, October 31, 1946, Record of the Bach Festival Society of W.P. 1949-51 Vol. 3, BFS 1936-92; Correspondence from Weldell Stone to Isabelle Sprague-Smith, December 11 1944, Sprague-Smith, Isabelle, Honorary Degrees, RCASC.

[12] Correspondence from B.C. to Isabelle Sprague-Smith, October 1, 1940, Record of the Bach Festival Society of Winter Park 1935-45, BFS 1936-92; Correspondence from Isabelle Sprague-Smith to “Alden,” November 10, 1947, Broadcasting Possibilities for the Bach Festival 1946-49, BFS 1936-92.

[13] “Knowles Memorial Chapel Dedicatory Plaque,” inscription carving, 1932, Knowles Memorial Chapel, Winter Park, Florida, viewed December 8, 2020.

[14] “Portrait of Frances Knowles Warren,” painting, n.d. Knowles Memorial Chapel, Winter Park, Florida, viewed December 8, 2020.

[15] Correspondence from Frances Knowles Warren to Hamilton Holt, April 1, 1932, Warren, Frances Knowles: Correspondence 1932-38, Warren, Frances Knowles, Trustee Files, RCASC.

[16] “Coming Festival,” Orlando Sentinel, March 27, 1937.

[17] “Contributions of Mrs. Frances Knowles Warren,” n.d. (after 1953), Warren, F.K: Trust Funds, Choir Fund, Gifts, Warren, Frances Knowles, Trustee Files, RCASC; Correspondence from Mary Lowe West to the Bach Festival Committee, January 17, 1938, Bach Festival General Correspondence 1937-39, Finances—Florida Symphony (hereafter cited as FFS), Records of the Bach Festival Society, Bach Festival, Music Programs, RCASC.

[18] Correspondence from Christopher O. Honaas to Frances Knowles Warren, March 27, 1939, Warren, Frances Knowles: Correspondence 1939-41, Warren, Frances Knowles, Trustee Files, RCASC.

[19] Correspondence from Isabelle Sprague-Smith to “Alden,” November 10, 1947, Broadcasting Possibilities for the Bach Festival 1946-49, BFS 1936-92.

[20] “Bach Festival Society of Winter Park: Sixtieth Anniversary,” (Winter Park: Bach Festival Society of Winter Park, 1995): 4.

[21] Isabelle Sprague-Smith, copyist, “Notes by Dr. C. Sanford Terry on the Mass in B Minor by Johann Sebastian Bach”, n.d.; Isabelle Sprague-Smith, copyist, “Cantata No. 178,” n.d. (circa 1946), Notes: Bach Research and Background Material, FFS.

[22] Correspondence from Albert Schweizer to Isabelle Sprague Smith, July 26, 1950, Record of the Bach Festival Society of W.P. 1949-51 Vol. 3, BFS 1936-92.

[23] Erwin R. Jacobi, “Schweitzer, Albert,” Grove Music Online, 2001; Christoph Wolff and Walter Emery, “Bach, Johann Sebastian,” Grove Music Online, 2001.

[24] Campbell, “Classical Music and the Politics of Gender,” 453.

[25] Correspondence from Mary Leonard to Hamilton Holt, n.d., Leonard, Mary Louise, Faculty Files, RCASC; “Founder of Winter Park Symphony Orchestra Is Community Leader,” Orlando Sunday Sentinel, February 19, 1933.

[26] Correspondence from Charles Atwood Campbell to Christopher Honaas and Herman Siewert, January 13, 1936, Bach Festival 1935-1936, BFS 1936-92.

[27] Christopher Honaas, “Noted Soloists to Sing,” Winter Park Herald, February 19, 1943; Photograph of Bach Festival Choir, n.d., circa 1943, The Bach Festival Society of Winter Park 1941-1944, FFS.

[28] “Katherine Carlo, 78, Pianist, Winter Park Music Teacher,” Orlando Sentinel, December 20, 1990.

[29] John V. Sinclair, interview by author, Winter Park, Florida, December 1, 2020.