by Wenxian Zhang

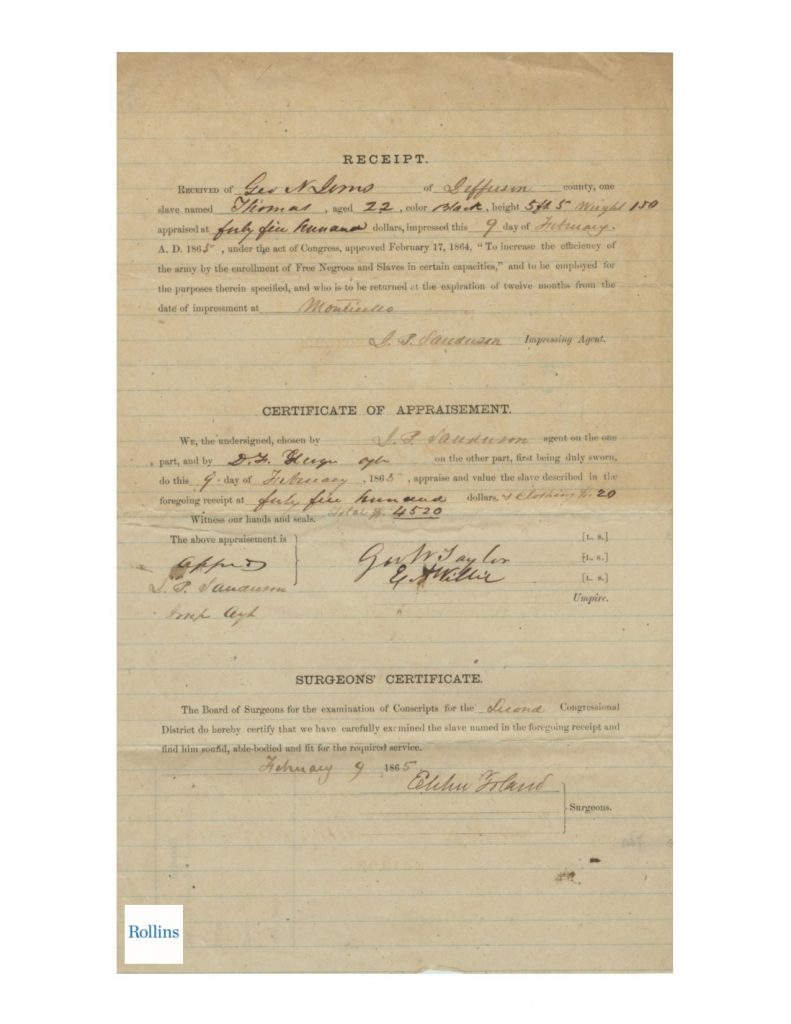

On June 19, 2021, our nation celebrated Juneteenth for the first time as a federal holiday commemorating the final emancipation of African American slaves 156 years ago. At Rollin College, an original “Receipt” and “Certificate of Appraisement” kept in the College Archives & Special Collections serves as a clear reminder of this disturbing chapter in American history before and during the Civil War (1861-1865).

Slave Impressment Receipt and Certificate of Appraisement

In 1955, ninety years after the conclusion of the Civil War, Frederick W. Dau donated the rare impressment receipt to the Mills Memorial Library at Rollins, along with several other precious items related to the early Florida history. Implemented during 1863-1865, impressment was a tax-in-kind legislated policy of the Confederate government to seize food, fuel, slaves, and other commodities to support military operations during the American Civil War.[1]

Born in 1880 and later graduated from the U.S. Naval Academy, Dau was a book editor and rare manuscript collector in the early twentieth century. After completing his service in the military, he edited magazines and journals such as the Mortgage Reporter and the New York Social Blue Book, and contributed to newspapers and other publications on mortgages, appraisals, and real estate. As the owner of one of the largest private libraries in America, he specialized in rare New York and Florida items. A historian himself, Dau also wrote a book about Florida history in 1934, Florida Old and New, which documented the state’s history from the time of the conquistadors all the way up to the Great Depression. Because of his personal and research interests in Florida history, during the 1930s, Dau befriended another well-known Florida scholar — A. J. Hanna (1893-1978), Professor of History at Rollins College — and their friendship eventually lead to Dau’s gift to Mills Library two decades later.

The one-page impressment receipt from Dau’s collection is dated February 9, 1865, exactly two months before the end of the Civil War. A transcription of the records is below. As a written record from the bygone era of slavery in the U.S., this primary source document reveals a great deal of information about the institution of slavery in Florida as a part of the Confederate States of America during the last days of its existence (February 8, 1861 to May 9, 1865).

RECEIPT

Received of Geo N. Jones of Jefferson county, one slave named Thomas, aged 22, color Black, height 5 ft. 5, weight 150, appraised at forty-five hundred dollars, impressed this 9 day of February, A.D. 1865, under the act of Congress, approved February 17, 1864, “To increase the efficiency of the army by the enrollment of Free Negroes and Slaves in certain capacities,” and to be employed for the purposes therein specified, and who is to be returned at the expiration of twelve months from the date of impressments at Monticello.

J.P. Sanderson, Impressing Agent

CERTIFICATE OF APPRAISEMENT

WE, the undersigned, chosen by J. P. Sanderson agent on the one part, and by D. G. George on the other part, first being duly sworn, do this 9 day of February, 1865, appraise and value the slave described in the foregoing receipt at forty five hundred dollars and clothing $20. Total $4520.

Witness our hands and seals,

APPRD. J. P. Sanderson

George W. Taylor

E. Wilbur

Umpire

SURGEON’S CERTIFICATE

The Board of Surgeons for the examination of Conscripts for the Leon Congressional District do hereby certify that we have carefully examined the slave named in the foregoing receipt and find him sound, able-bodied and fit for the required service.

February 9, 1865

Elihu Foland, Surgeons

George Noble Jones and His Family Heritage

From the written receipt, we can clearly see that Geo N. Jones (George Noble Jones) was the holder of a young, 22-year old enslaved African American named Thomas in Monticello, Jefferson County, Florida, who was appraised at $4,500 ($131,671 in 2021, adjusted for inflation since 1865) and conscripted by the Confederates for involuntary military service near the end of the Civil War. Since at that time enslaved individuals typically did not have last names, we do not know the eventual fate of Thomas in the Confederate Army; however, a great deal of information can be found about George Noble Jones (1811–1876), who was a wealthy American Southern plantation owner and great-great-grandson of Noble Jones (1701-1775). Among the first group of settlers to America, Noble Jones (George’s ancestor), arrived in the colony of Georgia as an immigrant from Britain along with James Oglethorpe (1696-1785) in 1733. He served as a doctor, military officer, Indian agent, royal councilor, and a surveyor of the colony during his long and productive lifetime.[2] Today his famous Wormsloe Plantation is the oldest standing structure in Savannah, GA.[3] His son, Noble Wimberley Jones (1724-1805), accompanied Noble Jones from Britain to Georgia at a young age, later became a member of the Provincial Congress of 1775, and was chosen as one of Georgia’s representatives in the Continental Congress. He was also a delegate to Congress in 1781, a leading physician within Georgia, and first president of the Georgia Medical Society. His son George Jones (1766-1838) was a local court judge, a member of the Georgia House of Representatives and Georgia Senate, and mayor of Savannah.[4]

Descended from a long line of wealthy colonial ancestors, George Noble Jones was born on May 25, 1811, to Noble Wimberley Jones II (1784-1818) and Sarah (Fenwick Campbell) Jones (1784-1843). Growing up in the South, he was well acquainted with plantation business, having managed a plantation in Jefferson County, Georgia owned by his mother and two aunts.[5] Jones would inherit part of this plantation, as well as considerable wharf and mercantile property in Savannah, Georgia, in addition to bank stocks and a range of other financial investments. On May 18, 1840, George Noble Jones married Mary Wallace Savage (Nuttall) (1812-1869) and purchased the Chemonie Plantation, as well as the Nuttall’s El Destino Plantation in Leon County, Florida.[6] In addition, he was also the owner of the Oscilla Eldorado Plantation in Florida. George Noble and Mary Wallace Jones together had four children: George Fenwick Jones, Wallace Savage Jones, Sarah Campbell Jones (Lillie Noble), and Noble Wimberley Jones III.

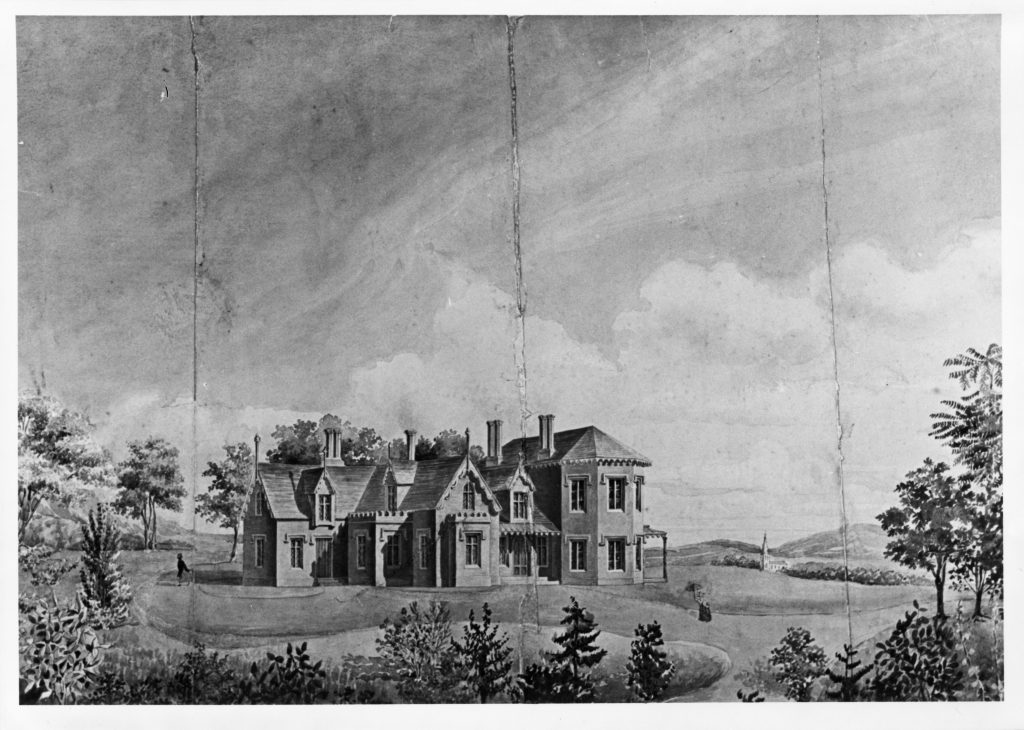

Richard Upjohn’s original 1839 watercolor of Kingscote (Image courtesy of the Library of Congress)

Besides his plantation business, G. N. Jones was also one of the first members of the elite gentlemen’s club, the Newport Reading Room, and known for Kingscote — one of the earliest summer “cottages” on Bellevue Avenue in Newport, Rhode Island. Designed by British architect Richard Upjohn in 1839, Kingscote was built as a classic Gothic Revival mansion and today is a historic landmark building listed in the National Register of Historic Places. Jones would become an absentee planter, preferring to spend his winter months in Savannah and the summer months at Kingscote during the Antebellum years leading up to the Civil War. After the war, as all his African American slaves were freed, his plantation business could not sustain its old way of operations. Consequently, his wealth declined considerably, and George Noble Jones was forced to sell his Rhode Island estate and instead take up residence on the El Destino plantation in the rugged Middle Florida region for the remainder of his life. He died in Jefferson County, Florida, in 1876 at the age of sixty-five.

El Destino and Chemonie Plantations

Although George Noble Jones owned and operated three plantations in Florida in the nineteenth century, most of the archival records available today with his name are from his El Destino and Chemonie Plantations. After Florida became a U.S. territory in 1822, English-speaking pioneers began to settle in the southernmost part of the U.S. Originally established by John Nuttall in 1828 with 52 enslaved African Americans, El Destino was a large cotton plantation of 6,683 acres located in western Jefferson County and eastern Leon County, Florida. In 1832, William B. Nuttall bought El Destino from his father’s estate for $17,000.[7] After Nutall’s death four years later, the property was left to his widow, Mary Savage Nuttall, a Savannah heiress who held 54 slaves and would also inherit another 80 slaves from her uncle, William Savage.[8] To employ those enslaved people, Hector Braden, a friend of William’s, sold Mary the Chemonie Plantation located only six miles north of El Destino.[9] On May 18, 1840, George Noble Jones married Mary Savage Nuttall and purchased El Destino. The plantation remained in the Jones family until well after the end of slavery and was finally sold 1919.

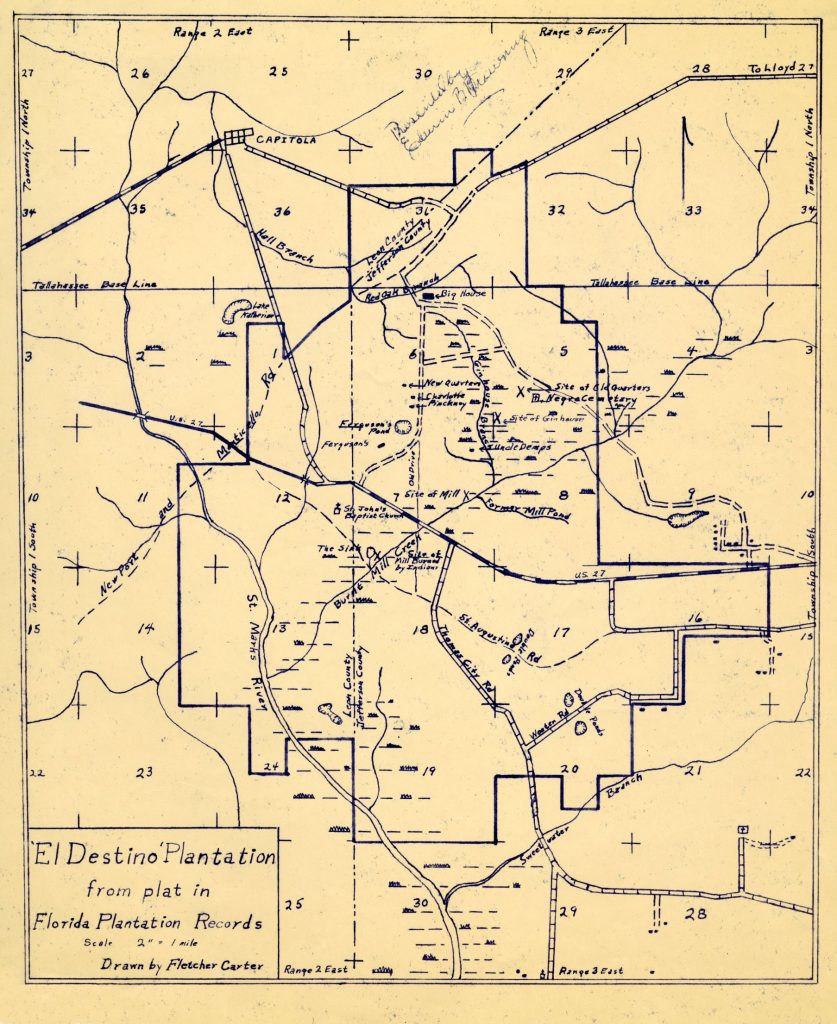

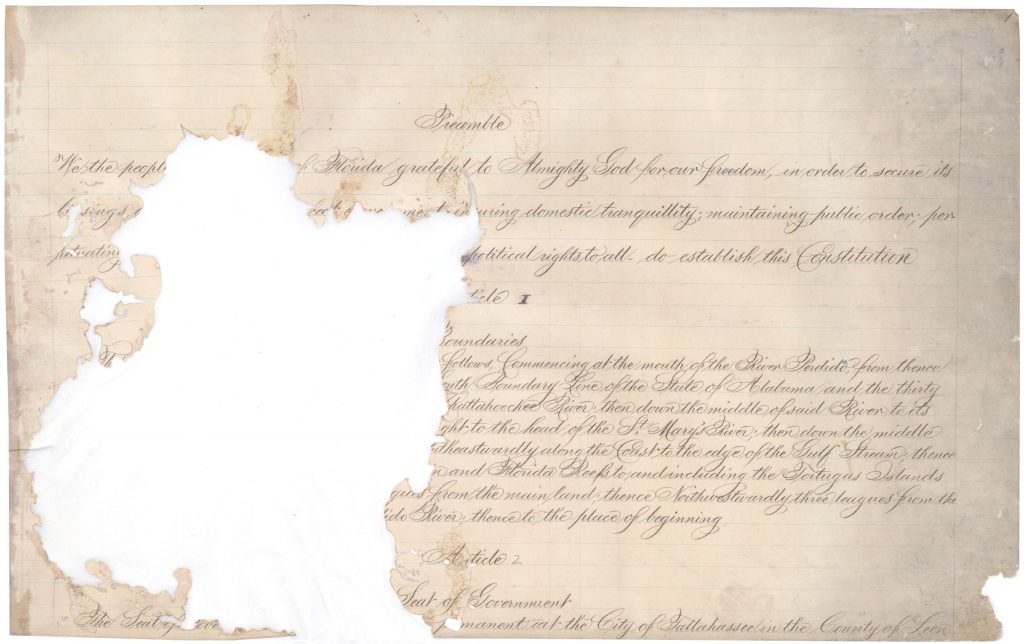

Map of the El Destino Plantation in Leon County, Florida (Image courtesy of Florida Memory)

Chemonie is a Seminole Indian term for soft and plaintive sounds or music.[10] Established by Hector Braden and situated on two separate tracts of land, Chemonie Plantation was a forced-labor farm of 1,840 acres in northern Leon County, Florida. The first tract was located between Centerville Road and the Monticello Road, occupying a large amount of land; the second tract was south and slightly east on the Leon County/Jefferson County line. Used primarily to produce cotton as a cash crop, the 1860 agricultural census in Leon County shows that the Chemonie Plantation had a total of 64 enslaved people. After its decline in agricultural use and its eventual sale by the Jones family, Chemonie was converted to a quail-hunting ground and corn production center in the twentieth century.

In 1927, Ulrich Bonnell Philips and James David Glunt published the Florida Plantation Records from the Papers of George Noble Jones, which provides rich, first-hand accounts of slavery in the Antebellum American South and its post-Civil War aftermath. A professor at the University of Michigan and Yale, Dr. Philips was an authority figure on the study of the American slavery in the first half of the twentieth century. Although he has often been criticized for his racist views toward African Americans and his romanticized interpretation of the Old South, this work remains an important primary source document for the study of slavery and the Southern plantation economy throughout the nineteenth century. According to Philips and Glunt’s transcriptions, there were 85 enslaved African Americans living on the Chemonie Plantation in 1855, and 142 at El Destino in 1865.[11] The book also includes details from the slave overseers’ reports, correspondence with the proprietor (George Noble Jones), plantation journals and tabulations for both El Destino and Chemonie’s assets, sundry lists of belongings and slaves, and other miscellaneous documents showing “a day in the life” perspectives from many on the plantations.

According to a list of slaves on El Destino Plantation organized by family groups, a child named Tom was listed in 1847 along with Nancy Florah and Prishanna, in addition to another child called Thommes who was listed with Stephen, Winey, Nat, and Coatney.[12] On the clothing distribution lists from the Chemonie Plantation, Tom was listed among the enslaved children who received both summer and winter clothes in 1851.[13] Another Tom appeared on the El Destino slavery inventory list in December 1854.[14] Then a minor named Tom (with L. Betty as parent) appeared among the slaves sold by Jones to Joseph Bryan for $200 in 1860.[15] In May 1865, another seven-year-old child named Tom appeared on the list of slaves at El Destino.[16] Apparently, Thomas/Tom was a common name for enslaved African Americans, as several other individuals named Tom were also listed in the journals kept by the overseers or mentioned in correspondence about plantation operations over years, which included their work assignments, when they stayed in the sick house, or their behaviors and punishments, etc.[17] Although we do not know for certain which Tom from the inventory is the individual listed in the 1865 receipt held in the Rollins College Archives nor do we know exactly which plantation he resided on, we do know that he was born into slavery in 1843 and was the “legal property” of George Noble Jones.

Confederate Florida and Enslaved African Americans during the Civil War

In March 1845, Florida was admitted as a slave state to the United States of America, becoming the 27th state in the Union at that time. In January 1861, Florida became the third Southern state to secede from the Union after Abraham Lincoln’s presidential election victory in November 1860. On the eve of the Civil War in 1860, Florida was still a frontier region and therefore had the smallest population of all the Confederate states, with only 140,424 residents, of whom 44% were enslaved African Americans and fewer than 1,000 were free people of color.[18] The state economy was largely based on plantation agriculture, which relied on enslaved African Americans working on large cotton and sugar plantations owned by wealthy white elites.

Although Florida sent around 15,000 troops to the Confederate army, the state during the Civil War served primarily as a source of food and supplies for the Confederate military; and as such, Confederate authorities used enslaved people as laborers to produce and transport those items. On January 1, 1863, President Lincoln issued the Emancipation Proclamation, which declared freedom for all enslaved people in the South that remained under Confederate control. After the Union troops encouraged enslaved African Americans in plantations to flee their holders in search of freedom, some African American slaves in Florida did manage to escape and enlisted as soldiers in the United States Colored Troops or as sailors in the Union Navy.[19] As the war went on, extensive casualties and increased desertions led to the South’s first Conscription Act on April 16, 1862,[20] which called for the enrollment of all white males between the ages of 18 and 35 for military service in the Confederate Army for a period of three years.[21] However, the Conscription Act was deeply resented by Floridians for its uneven execution, since it allowed exemptions for plantation owners and overseers that held twenty or more enslaved African Americans, and allowed wealthier people to pay poorer men to serve on their behalf rather than joining the battles themselves.

In addition to their disdain for unjust conscription laws, Southerners were equally fed up with the impressment policies during the war years, which allowed Confederate agents to locate and secure supplies at fixed prices for military use. After the first impressment law was passed in March 1863, as the South was facing escalating losses on the battlegrounds, on February 17, 1964, the Confederate government approved “An Act to Increase the Efficiency of the Amy by Employing Free Negroes and Slaves in Certain Capacities.”[22] This is the specific law cited in the Impressment Receipt and Certificate of Appraisement wherein the enslaved Thomas was conscripted in Jefferson County, Florida on February 9, 1865, for his 12-month involuntary service in the Confederate Army. Not surprisingly, this last-ditch effort not only bred much resentment amongst property owners of all kinds across the South, but also did not help the fate of the Confederate States of America. Worse still, conscripted slaves found themselves in a particularly painful form of military service — fighting and dying to defend the evil institution of slavery that was to be soon eradicated at the end of the war. According to the records from the National Archives, during the Civil War, the enslaved were given especially odious and labor-intensive jobs and even though some were entitled to compensation, the majority of that pay often went to the Southern white plantation owners who called them property. Moreover, when enslaved African Americans died, escaped, or were freed by Union forces, these salve holders filed claims for the “loss of property” with the Confederate government.[23] Many manhunts were led with the sole purpose of returning escaped slaves to his/her holder even after the war ceased.

The Importance of Historical Preservation

The 1865 Impressment Receipt and Certificate of Appraisement held in the Rollins College Archives serves as a powerful reminder of the painful and ugly history of slavery in the United States and the State of Florida. Despite the fact that the Civil War took place more than 160 years ago and hundreds of thousands of Americans lost their lives in the bloody battles while millions suffered its terrible aftermath, there has been and still remains a long-held misperception that the Confederacy was somehow a noble “lost cause,”[24] or that “most black and white southerners had long lived together in harmony.”[25] After going through this research experience, I now reflect on how sad and shameful it is that we can easily trace the family heritage of the Jones family today all the way back to Britain, but we cannot, even with all the resources we now have at our disposal online, determine who the enslaved Thomas was or who his family might have been! Such historical silences are a product of the institution of slavery and may never be fully corrected.

Some readers may wonder why the College Archives holds a document that deals with the experiences of plantation slavery and Civil War history, considering that the College was not founded until 1885. As a research partner on campus, we feel primary source materials that predate our institution, such as this receipt, can tell us more about what happened in the distant past and contextualize our community’s long history. Furthermore, our shared history is humanized through these artifacts, making them not only good research materials for scholars, but also wonderful teaching resources for our community of learners. Archivists, as information professionals, have the duty to preserve historical realities and highlight these documents. We strongly believe that no matter how disturbing the subject matter, it is critical for all Americans to know and remember our past as a slave society and not shy away from the history that followed it as a result after emancipation. By unpacking the complicated history encapsulated in this single slave impressment receipt, the archival record can participate in and contribute to the illumination of historical facts and help dispel harmful myths about plantation life, like the idea of the idyllic “Old South.” As we celebrate the Juneteenth emancipation and solute those who fought and died for freedom and liberty in the nineteenth century, we acknowledge that racism is still a profound social problem in twenty-first century America and we all need do our part to ensure inclusion, equity, and justice for all.

[1] Mary DeCredico, “Confederate Impressment during the Civil War.” Encyclopedia Virginia, Virginia Humanities, Dec. 7, 2020. https://encyclopediavirginia.org/entries/confederate-impressment-during-the-civil-war/.

[2] Georgia Department of Natural Resources, “Wormsloe: State Historic Site Savannah,” https://gastateparks.org/Wormsloe.

[3] Ibid.

[4] Georgia Historical Society, Jones Family Papers 1723-1936. http://ghs.galileo.usg.edu/ghs/view?docId=ead/MS%200440-ead.xml.

[5] Florida Historical Society, Guide to the El Destino Plantation Papers 1786-1938 (Mss. Collection #2001-02). https://myfloridahistory.org/content/el-destino-plantation-papers-1786-1938.

[6] Ulrich Bonnell Phillips and James David Glunt(eds.), Florida Plantation Records from the Papers of George Noble Jones (St. Louis: Missouri historical society, 1927). https://babel.hathitrust.org/cgi/pt?id=mdp.39015011232298&view=1up&seq=1&skin=2021.

[7] Florida Historical Society, Guide to the El Destino Plantation Papers 1786-1938.

[8] Ibid.

[9] Ibid.

[10] Florida Plantation Records from the Papers of George Noble Jones, 18.

[11] Ibid, 511-512 & 562.

[12] Ibid, 329-330.

[13] Ibid, 430-434.

[14] Ibid, 549-550.

[15] Ibid, 558-559.

[16] Ibid, 569.

[17] Ibid, 111, 151-53, 187, 213, 293, 300-301, 303, 308, & 313.

[18] Charlton W. Tebeau, A History of Florida (University of Miami Press, 1999), 157-158.

[19] R. Boyd Murphree, “Florida and the Civil War: A Short History,” State Archives of Florida. https://www.floridamemory.com/learn/research-tools/guides/civilwarguide/history.php.

[20] “An Act to Further Provide for the Public Defense.” April 16, 1862. The Statutes at Large of the Confederate States of America, Commencing with the First Session of the First Congress; 1862, 29-32. https://docsouth.unc.edu/imls/statutes/statutes.html.

[21] Murphree, “Florida and the Civil War: A Short History.”

[22] Adjutant and Inspector-General’s Office, Confederate States of America, “Circular [Concerning Employing Free Negroes and Slaves in Certain Capacities.]” February 17, 1864. Documenting the American South. https://docsouth.unc.edu/imls/circular/circular.html.

[23] Michael E. Ruane, “During the Civil War, the Enslaved Were Given an Especially Odious Job. The Pay Went to Their Owners.” Washington Post, July 9, 2020. https://www.washingtonpost.com/history/2020/07/09/national-archives-slavery-payroll-receipts-civil-war-confederacy/.

[24] Paul Duggan, “The Confederacy Was Built on Slavery. How Can So Many Southern Whites Think Otherwise?” Washington Post Magazine, November 28, 2018. https://www.washingtonpost.com/news/magazine/wp/2018/11/28/feature/the-confederacy-was-built-on-slavery-how-can-so-many-southern-whites-still-believe-otherwise/.

[25] Leslie Postal, Beth Kassab and Annie Martin, “Schools without Rules: Private schools’ Curriculum Downplays Slavery, Says Humans and Dinosaurs Lived Together.” Orlando Sentinel, June 1, 2018. https://www.orlandosentinel.com/news/education/os-voucher-school-curriculum-20180503-story.html.