Wenxian Zhang

When the COVID-19 pandemic broke out, the Wuhan Institute of Virology (WIV) became the center of the global attention because of its early reporting and coronavirus-related research. However, not too many people know that WIV’s founding director Harry Gao (高尚荫March 3, 1909 – April 24, 1989) was a Rollins alumnus. After receiving his BS from Rollins in 1931, Gao pursued graduate studies at Yale, where he earned his PhD in 1935. Upon returning to China at the age of 26, Gao became then the youngest professor at Wuhan University, one of the top ten Chinese universities, and eventually rose to become vice president. As a member of the Chinese Academy of Sciences, he was was one of the founders of virology in China, establishing the first virology research institute, the first microbiology major, and the first virology major of China.[1] Gao was also one of very few people of Asian heritage in the college history to have received the Rollins Decoration of Honor (1946) and an honorary Doctor of Science (1981). His distinguished career and lifetime achievements not only validate Gao’s intelligence and tenacities, but also demonstrate the value of liberal arts learning and the importance of international education, both of which are core principles of a Rollins education.

International Student at Rollins

Although Rollins began to admit Cuban students at the end of the nineteenth century, this work was not so much mission-driven but rather out of economic necessity. Only after Hamilton Holt was appointed president in 1925 did Rollins start to make major efforts in recruiting international students. Before coming to Rollins, Holt was an ardent internationalist in the early 20th century and a strong advocate for Woodrow Wilson’s proposal on the League of Nations. He traveled widely to promote American membership in the international peace keeping enterprise, not only in Europe but also in Asian countries such as China and Japan. After arriving in Florida, Holt endeavored to diversify the small community of learners at Rollins in Winter Park, and as a result the College witnessed a sizeable increase in international students from Europe, Latin America and Asia during the Holt era (1925-1949).

President Holt with foreign students in 1930. Harry Gao was the first on the third row from the left, Wu-fei Liu stood to Holt’s right, Yasuo Matsumoto of Japan sat second from the left. Other students came from Austria, Brazil, Czechoslovakia, France, Germany, Hungary, Iraq, Norway, Russia, Turkey, and Uruguay.

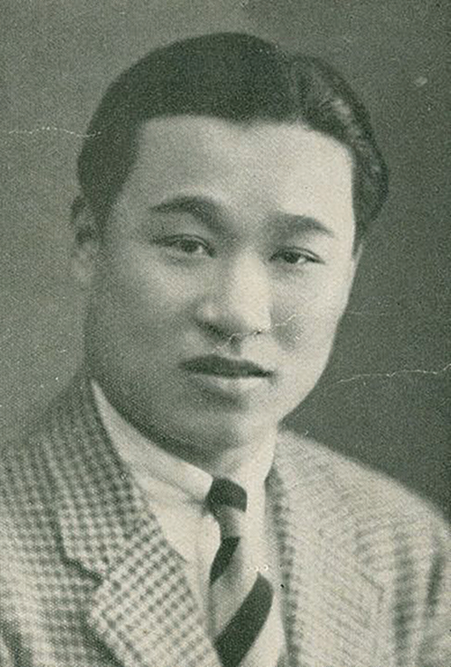

The first Chinese student ever enrolled at Rollins was Ling Nyi Vee, from Fuzhou, China, who initially attended Wesleyan in 1926-28 and then received her AB from Rollins in 1929.[2] A year later, Harry Charles Gao (H. Zanyin Gaw) became the second Chinese student to study at Rollins. Born on March 3, 1909 to a wealthy family of scholars in Jiashan County, Zhejiang Province, Gao was the youngest of three siblings, whose older sister Helen Gao (高蔼鸿) was also educated in the United States and later married to Dr. Wu-chi Liu (柳无忌) of Indiana University. In 1916, Gao attended the Taozhuang School founded by his father for his primary education. At a young age, he demonstrated a strong curiosity in anything and everything from the natural world, and he was fascinated by the connection between the local practice of raising silkworms and associated insect diseases in the area. In 1926, Gao enrolled in Soochow University, a well-regarded private institution founded by Methodists in Southeast China. Studying under the famed entomologist Wu Chenfu (胡经甫), Gao excelled academically; he was also a star athlete and a member of the varsity basketball and tennis teams. After earning his BS in biology in 1930 and through his family connection, Gao received a scholarship and became an exchange student at Rollins College alongside with Wu-fei Liu (柳无非) ’34 from Shanghai, China.

The student bugler, pictured in the 1937 Tomokan yearbook

At Rollins, Gao stayed in a dorm room in Chase Hall where the college bugler regularly sounded the horn to announce classes right under his window. He also adopted an American nickname — Harry — which was given to him by classmates who tended to stumble over the pronunciation of his Chinese name Shangyin.[3] Since he had already earned his bachelor degree before arriving at Rollins, Gao again continued to prove his intellectual propensity, passing all his courses with ease while also adopting the very different conference style instruction strategy that was so unique at Rollins of the time. He was also an active member of the Rollins League of Nations, which included international students from 12 other countries,[4] in addition to the Cosmopolitan Club. The later was designed to promote mutual understanding and friendship between American and international students. Advised by Professor Edwin L. Clarke of Sociology, the Cosmopolitan Club invited well-known speakers to give talks on issues of international importance, organized presentations by foreign students about their respective countries, and sponsored the Inter-Racial Conference at Florida Southern College in Lakeland, among others.[5]

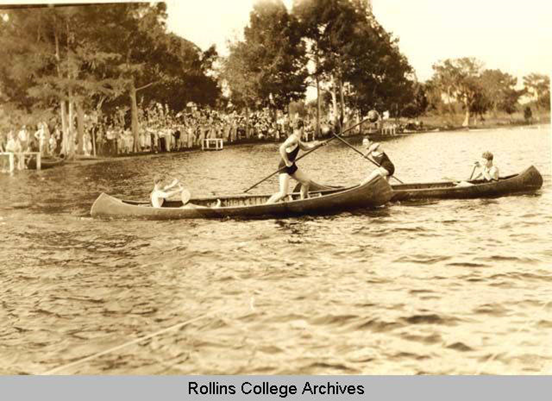

Canoe tilting on Lake Virginia was one of the favorite aquatic sports of Rollins students in the early 20th century.

During his 50th homecoming anniversary in 1981, Gao fondly recalled his student days at Rollins. “When I arrived on the campus, I was amazed to see the magnificent changes that had taken place since my days. The college is more beautiful than ever. When I walked along the Walk of Fame, I could easily spot the Confucius stone. At the moment I stepped into Chase Hall, where I stayed, I felt as if I was coming back from my classes at Knowles Hall. At the shore of Lake Virginia, I couldn’t help recalling the swimming lessons I had from Fleet and the war canoe race I participated in. These pleasant memories brought me back to the old days and how much I really wished that I might be at Rollins again as a student. Rollins to me always personifies beauty, culture, and friendship.”[6]

Teaching and Research during a Turbulent Time

After receiving his BS from Rollins, Gao conducted graduate study at Yale and earned his PhD in 1935. By then, after being far from China for more than five years, he was eager to return home, especially since his mother was critically ill. Meanwhile, the country was also facing increasing threats of military aggression from Japan, which made advanced scientific research almost impossible. Just before embarking on his journey, he received a telegraph that his mother had already passed away. Despite his friends’ recommendations of stay-put, Gao felt that as an educated Chinese he could and should do his part to help his motherland. After pursing a short-term fellowship at the London School of Tropical Medicine and Hygiene, he returned to China in August 1935 and was appointed as an instructor at Wuhan University. He was soon after promoted to assistant and associate professor in biology. By 1942, Gao was already a full professor of microbiology at the premier institution of higher education in China.

In 1937, Gao married Niancui Liu (刘年翠) of Wuhan University; however, his family life was abruptly interrupted when the Sino-Japanese War broke out. Consequently, Wuhan University was forced to relocate to the more interior region of Leshan, Sichuan Province. Despite these extreme difficulties, Gao continued to pursue research related to virology while actively contributing to the Chinese national defense against Japanese belligerence. In his letter of Nov. 20, 1937 to President Holt, he wrote: “As an advocate of international peace, you are probably well-informed about the present conflict between China and Japan. Since the major hostilities started about three months ago, our loss has been tremendous. The Japanese airplanes are bombing everywhere, especially educational centers. Many colleges and universities were destroyed. This is the most critical moment in the history of the nation. To fight means to exist and therefore, in spite of the handicaps we are facing, we must struggle along. While our brave men are fighting at the front lines, we who stay behind are trying hard to give them our whole-hearted support. The staff members of this university contribute more than fifty percent of their incomes every month to the armies for the maintenance of military hospitals. There are thousands and thousands of wounded men who need to be taken care of. At the same time our students are training to do nursing work.”[7]

Biology Professor Gao Shang-yin standing outside the Microbiological Laboratory of Wuhan University located in Leshan (Chiating), Sichuan Province in May 1943. Photo courtesy of Joseph Needham of the Needham Research Institute, under Creative Commons attribution & non-commercial use license.

Harry Gao (2nd from right) with other faculty members of Wuhan University in Leshan, Sichuan Province in May 1943. Photo courtesy of Joseph Needham of the Needham Research Institute, under Creative Commons attribution & non-commercial use license.

On August 19, 1938, Japanese bombers blasted Leshan killing 15 faculty and staff members of Wuhan University while injuring dozens more. The blast also destroyed thousands of books and caused massive facility damages. In another letter to Holt dated on Feb. 9, 1940, Gao noted: “I am glad to tell you that in spite of the bombing done by the Japanese, we are carrying on our work as usual. Since Wuhan was fallen into the hands of our enemies, the university has long been moved to the present site. For the last two years we have been working very hard to adjust ourselves at our new location.”[8] In his reply of April 2, 1940, Holt wrote: “It was certainly good to get your letter of February 9. I have thought of you many, many times during these last tragic years, and although, as you know, I was one of the Founders of the Japan Society and have been decorated by the Emperor, I am completely alienated from the Japan’s conduct of the war and hope, as all Americans do, that China will regain her independence and integrity.”[9]

Even in the face of such turbulence, Gao persisted with his academic teaching and research, publishing dozens of scholarly articles in scientific journals in the United States, China, England, and Germany on various topics in microbiology. Notable among them was his scientific research on the Chinese soil bacteriology that appeared in the 1941 issue of Nature.[10] After visiting his lab in Leshan, Joseph Needham, a well-regarded British biochemist, historian, and sinologist known for his scientific research and writing on the history of Chinese science and technology, wrote a strong letter of recommendation on behalf of Gao. “I would say that I know Gao Shang-Yin (his own style is H. Zanyin Gaw) well, having visited his laboratory at Wuhan University, Chiating, Szechuan. Though I am not of the same subject as he, I would say that so far as I am able to judge, his scientific standing is on the border of first and second rate; but it should be realised that he has done a wonderful job in keeping an active research school alive in conditions and difficulties which no one who has not seen them personally in China can properly appreciate… I know of no Chinese biologist who better deserve a chance to show what he can do in favourable surroundings.”[11] Therefore, with glowing endorsements such as this, Gao won a prestigious grant award at the end of World War II that enabled him to pursue a sabbatical at Princeton in 1945-46, where he conducted advanced virus studies at the Rockefeller Institute for Medical Research under the guidance of Nobel Prize Winner Wendell M. Stanley.

On June 5, 1946, fifteen years after his graduation, Gao had his first homecoming at Rollins and received the prestigious Rollins Decoration of Honor. At the commencement ceremony, President Holt pronounced: “Harry Gaw, it is a pleasure and privilege to welcome you back to the Rollins’ campus and especially to award this honor to a citizen of a great and ancient—and yet modern—nation which has emerged so nobly from the conflict with Japan and whose future is sure to be second to none in the evolution of human civilization. You are a man of both achievement and promise and your Alma Mater is proud of you.”[12]

Missed Opportunity in America

While in the United States conducting advanced research, the Civil War between the nationalist government and the communist forces broke out in China. Again, these political developments profoundly affected Gao’s life. On Nov. 12, 1946, Gao wrote from Princeton to President Holt: “Things are from bad to worse in China, not only politically but also economically. The news I received from friends there has not been very encouraging. In fact, many of them advised me to stay in this country for a while, as the whole country of China is in a state of chaos. The educational institutions are running nominally, but the intellectual atmosphere is lacking. Everyone is facing the problem of having enough to live on. There is no way of carrying on any kind of academic work… I feel I am a Chinese and my place is in China. But for the present, it is wise for me to stay away because it will be very difficult for me to make enough to feed the family, as things are now in China.”[13]

Harry Gao and his wife Niancui Liu of Wuhan University. Courtesy of the Chinese Academy of Sciences.

While Gao helped his brother-in-law Wu-chi Liu of the National Central University escape the Chinese Civil War by securing a visiting professorship in English at Rollins in 1946-48, there was not a position open at that time in either Biology or Chemistry in Winter Park. Therefore, Gao returned to Wuhan to resume his teaching in the spring of 1947. In another letter to Holt dated on Sep. 15, 1947, Gao wrote: “As long as there is no peace, people will suffer. The worst thing of course is the terrific inflation. Everyone is having a hard time to keep himself alive. The universities are keeping up but there is no fund for laboratory experiments, books and other things essential for academic work. To carry on research is not possible. Even teaching is quite a problem. Good days will never come until there is peace in China. The future seems pretty dark but we hope things will be better off in due course of time… Life in China is too hard and you cannot do anything.”[14]

Harry Gao and his family in China in 1949. Courtesy of the Chinese Academy of Sciences.

As the Chinese Civil War proceeded, conditions in Wuhan began to deteriorate rapidly. On Feb. 11, 1949, in a desperate attempt to leave the country, Gao pleaded Holt to help him secure an academic position in the United States. “The situation in China is serious. The communists are pushing rapidly southward towards where we are. Nanking our national capital, is being threatened. Although President Chiang Kai-Shek has resigned and ‘peace talk’ is now being carried on, we doubt very much if the communist really want peace and to lay down their arms. The whole country is in a state of chaos and uncertainty. On top of the political and military crisis the economic situation is just hopeless. The inflation is getting worse everyday and the people are having the most dreadful time, much worse than the war years. The University here is carrying on although many students as well as faculty members have left. It is likely that the University will have to stop functioning when things get worse. The main difficulty is finance. We can hardly keep ourselves alive with what we get as our regular pay… Time is running short as the communists are getting nearer and nearer. Once the place falls into the hands of the communists it may be impossible for anyone to leave.”[15]

Hearing Gao’s distressed call for help, Holt immediately went into action by writing letters to his friends about any possible openings in other American institutions. Finally, the University of Florida responded positively by offering Gao a biology visiting professorship in Gainesville. However, this deal was too late for Harry. On June 8, 1949, in his last letter to Holt, Gao wrote: “The world with us has been changed since I wrote to you last. We are now under the communist government and everything is fine. This city was taken over on May 17th, without resistance. We were lucky to get through without any serious damage. Prof. Sherman’s cable of confirmation of my appointment as Visiting Professor of Biology was received on the day before May 17th. Of course under the present circumstances it will not be possible for me to make the trip to Gainesville mainly because the new government does not have diplomatic relationship with U.S. and further more I am not at all sure what the policy of the new government is in respect to scholars going abroad for academic work.”[16]

Honorary Doctor of Science

While Gao tried to figure out what to do with his life, his research on Chinese virology was published in the 1949 issue of Science.[17] Despite the significant trauma during the war years, things did not turn out as dark as Gao feared. After the Civil War and the People’s Republic of China was founded, normal academic life gradually resumed at Wuhan University. Because of his scientific accomplishments, Gao was appointed the chair of the Biology Department in 1949. Although his field was in natural science, Gao had the political expertise to know that in order to advance his academic career he must declare his full support for the new republic. Through dedication and hard work, in the ensuing years Gao won the “Model Worker” and “Model Professor” awards of Wuhan University multiple times; and in 1956, Gao joined the Chinese Communist Party. During the same year, he also founded the Wuhan Microbiology Laboratory under the Chinese Academy of Sciences, which was later renamed the Wuhan Institute of Virology. As a leading scholar in virus studies for plants, insects, and animals, Gao made significant contributions to the development of virology in China, publishing five books and more than 100 papers over his long and productive career. In 1980, Gao was elected an academician of the Chinese Academy of Sciences, a lifelong honor given to Chinese scientists who have made substantial achievements in various fields. Along with his scholarly endeavors, Gao also rose steadily within the ranks of academic administration. He served as deputy dean of the College of Sciences and Provost of Wuhan University. He was also director of the South China Institute of Microbiology, associate director of the Wuhan Branch of the Chinese Academy of Sciences, and eventually was appointed as vice president of Wuhan University.

Although Gao only studied one year in Winter Park, Rollins held a special place in his heart. In 1979, soon after diplomatic relations resumed between America and China and through the work of a special Yale-China program, Gao revisited the United States after decades of isolation and enjoyed a second homecoming to Winter Park, at which time he was warmly received by President Thaddeus Seymour (1978-1990).[18] Deeply touched by the hospitality he experienced in the U.S., and as vice president of the Friendship Association with Foreign Countries in Hubei, Gao dedicated himself to enhancing mutual understanding and friendship between Chinese and American peoples. In his letter to the Rollins Alumni Office, Gao wrote: “I do hope that the exchange program between Rollins and my university will be materialized and will flourish as the years go by. Personally, I shall be more than happy to see Rollins people on our campus and our people on Rollins’ campus. Friendship is based on mutual understanding and mutual understanding depends on contacts. My Rollins experience fully confirms this concept.”[19]

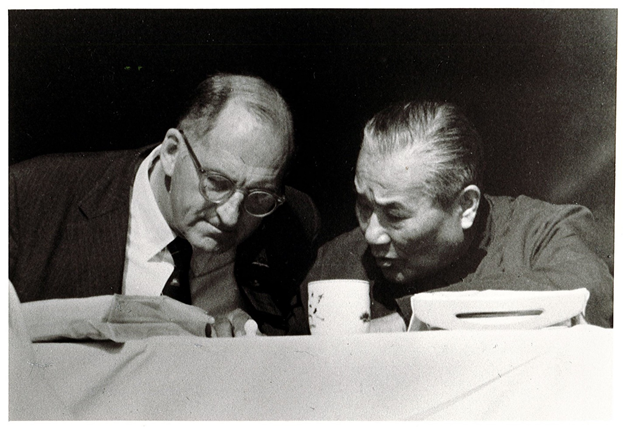

President Thaddeus Seymour with Harry Gao at Wuhan University in 1983.

For his impressive academic achievements and noteworthy efforts in promoting international exchanges, Rollins’ Board of Trustees decided to award Harry Gao an Honorary Doctor of Science in 1981. At the commencement ceremony on Sunday, May 24, 1981, President Seymour presented the honorary citation to Gao:

“You graduated from Rollins with the Class of 1931, exactly 50 years ago, and you left your mark. That is not all you left. You gave Hamilton Holt a stone from the birthplace of the Confucius, and it has been a part of Walk of Fame for half a century… After Rollins, it was a PhD from Yale and the start of a career of international prominence through research on the herpes virus. Your recent election to the Chinese Academy of Sciences recognized your distinguished career as microbiologist and as Chairman of the Department of Virology and as Vice President of Wuhan University. In recent years, you have been an ambassador for better understanding between our two nations, arranging exchange programs with Yale, Seton Hall, and Indiana University… You have expressed your love for Rollins in many ways, and we return it today, with respect, with admiration, above all, with deep affection. By virtue of the authority vested in me by the Board of Trustees, I confer upon you the honorary degree of Doctor of Science, with all the rights, privileges, and signal obligations thereunto appertaining.”[20]

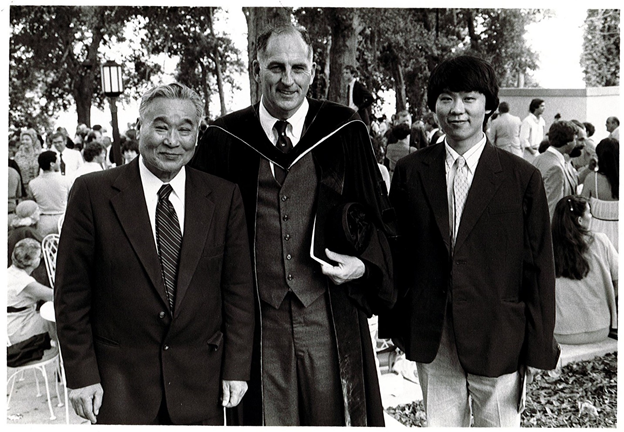

President Seymour with Harry Gao and his son Min Gao at the commencement, May 24, 1981.

To accept this personal recognition, Gao passionately remarked: “I consider that the honorary degree of Doctor of Science conferred upon me by Rollins is not to me as a person, rather [it serves] as a symbol of respect and friendship to my university and to the Chinese people. I am indeed touched by the warm reception I received at Winter Park… After Rollins, I went to Yale for my graduate studies. My Rollins training helped me tremendously in adjusting myself academically and socially at New Haven. After Yale, I went back to China to serve my country. If I succeeded in some way and did something for my own people during my long academic career, I must say that I was influenced by the liberal education of Rollins, the outstanding personality of President Hamilton Holt, and the good friendship of fellow students. Rollins did give me things that I shall always cherish. So when I came back this time to visit the campus after half a century, I felt I was returning home.”[21]

After returning to China, Gao pushed to advance the exchange program between Rollins and Wuhan University. Soon after, his son George Gao Chao became the first Chinese student to study at Rollins after the Cultural Revolution, and Professor Charles Edmondson became the first Rollins faculty member to spend his sabbatical leave in Wuhan. President Seymour also visited Gao for a major anniversary celebration of Wuhan University in 1983. On April 24, 1989, Harry Gao died of a heart attack on the eve of meeting with a visiting American scientist in Wuhan. His death was reported nationally by the Xinhua News and People’s Daily. To celebrate his life as a prominent scientist in China, a bronze statue of Gao was dedicated at the College of the Life Science at Wuhan University on October 13, 2018.

Statue of Harry Gao at Wuhan University. Image courtesy of Wuhan University.

Acknowledgement

The author gratefully acknowledges the research assistance provided by Ms. Chao Chen, Wuhan University alumna and research librarian at Tufts University

[1] H. Liu, H. Zhang and D. Chen “I Make Efforts, People Make Comments: Prof. H. Zanyin Gaw – Pioneering the World, the Trailblazer and Founder of China’s Virology Research.” Protein Cell. 6:12 (2015), 859-861. doi:10.1007/s13238-015-0227-4.

[2] Tomokan Yearbook (Winter Park: Rollins College, 1929), 53. https://scholarship.rollins.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1085&context=tomokan.

[3] “H. Gao Shang Yin Honorary Degree Citation,” Honorary Degree Files, Rollins College Archives, Winter Park, Florida.

[4] “Rollins League of Nations,” Rollins Alumni Record, December 1930, 15. https://scholarship.rollins.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1318&context=magazine.

[5] Tomokan Yearbook (Winter Park: Rollins College, 1931), 156. https://scholarship.rollins.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1000&context=tomokan.

[6] “Remarks by Harry Gao on the Occasion of Receiving His Honorary Degree in 1981,” 150E Alumni Files, Rollins College Archives, Winter Park, Florida.

[7] “Former Chinese Rollins Student Writes Dr. Holt.” Rollins Sandspur, January 19, 1938, 3. https://stars.library.ucf.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1509&context=cfm-sandspur.

[8] Harry Gao to Hamilton Holt, Feb. 9, 1940. 150E Alumni Files, Rollins College Archives, Winter Park, Florida.

[9] Hamilton Holt to Harry Gao, April 2, 1940. 150E Alumni Files, Rollins College Archives, Winter Park, Florida.

[10] HZ Gaw, “Soil Protozoa in Some Chinese Soils.” Nature 147 (Jan.-Jun. 1941), 390.

[11] Joseph Needham to Ross Harrison, Feb. 28, 1945. Sterling Library Archives, Yale University, New Haven, Connecticut.

[12] “Two Alumni Honored at Commencement.” Rollins Alumni Record, June 1946, 4-5. https://scholarship.rollins.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1261&context=magazine.

[13] Harry Gao to Hamilton Holt, Nov. 12, 1946. 150E Alumni Files, Rollins College Archives, Winter Park, Florida.

[14] Harry Gao to Hamilton Holt, Sep. 15, 1947. 150E Alumni Files, Rollins College Archives, Winter Park, Florida.

[15] Harry Gao to Hamilton Holt, Feb. 11, 1949. 150E Alumni Files, Rollins College Archives, Winter Park, Florida.

[16] Harry Gao to Hamilton Holt, June 18, 1949. 150E Alumni Files, Rollins College Archives, Winter Park, Florida.

[17] H. Zanyin Gaw and H. P. Wang, “Survey of Chinese Drugs for Presence of Antibacterial Substances.” Science 110:2844 (1949), ll-12.

[18] “Rollins Alum Visits from Peoples Republic of China.” Rollins Alumni Record, September 1979, 3. https://scholarship.rollins.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1113&context=magazine.

[19] Harry Gao to William Gordon, July 21, 1981. 150E Alumni Files, Rollins College Archives, Winter Park, Florida.

[20] “H. Gao Shang Yin.” May 24, 1981. 43A Honorary Degree Files, 150E Alumni Files, Rollins College Archives, Winter Park, Florida. [1] Harry Gao to William Gordon, July 21, 1981. 150E Alumni Files, Rollins College Archives, Winter Park, Florida.

[21] Harry Gao to William Gordon, July 21, 1981. 150E Alumni Files, Rollins College Archives, Winter Park, Florida.