By Jack C. Lane

Let us think of Pinehurst as The Grand Old Lady of the Rollins campus, a regal gentlewoman residing on the East side of the Horseshoe Commons at the very spot where she came into existence in 1886. Despite all the changes she has witnessed, the lady stubbornly refuses to alter her Queen Anne style, a design highly valued among New England Victorians who gave her life. She can still observe unimpeded the goings and comings on the Commons (Horseshoe), but on her other three sides the view is now obscured by a host of Spanish Mediterraneans. Their style is not exactly to her taste, but by now she has learned the virtue of tolerant co-existence.

Over the years, she suffered the loss of her two closest friends. On one side, Monsieur Francis Knowles was tragically consumed by fire in 1909 and Monsieur Loring Augustus Chase on the other recently suffered the humiliation of the wrecking ball. The loss of the latter companion of over one hundred years was particularly painful. Nevertheless, the lady remains stoically impervious to such afflictions because she is no stranger to adversity, because she takes pride in her role as the sole remaining visual reminder of the college’s early years and because the young people of every generation have embraced her with loving kindness. She just celebrated her 136th birthday this past March.

In her early years, Lady Pinehurst was referred to as a cottage, a term that had a special meaning for Victorian educators. In this era of in loco parentis, the cottage concept of boarding was deemed essential because college leaders wanted to replicate the familial characteristics of home. Early Rollins College brochures claimed the cottage system encouraged young people to develop the proper character and habits; a live-in “house mother” and even some live-in faculty gave assurance to parents that the college imposed the same kind of good behavior that parents demanded at home. Here was how the George Morgan Ward administration described the cottage concept.

The “cottage” system, so popular in the best educational institutions, is the rule at Rollins. One of the distinctive features of the [cottage system] is to provide home life for its students. The students live in cottages along with matrons and members of the faculty who have charge of them. The purpose is to control the student by such salutary restrictions as parents would impose, and to surround them with cheerful and refining influences of a Christian home.

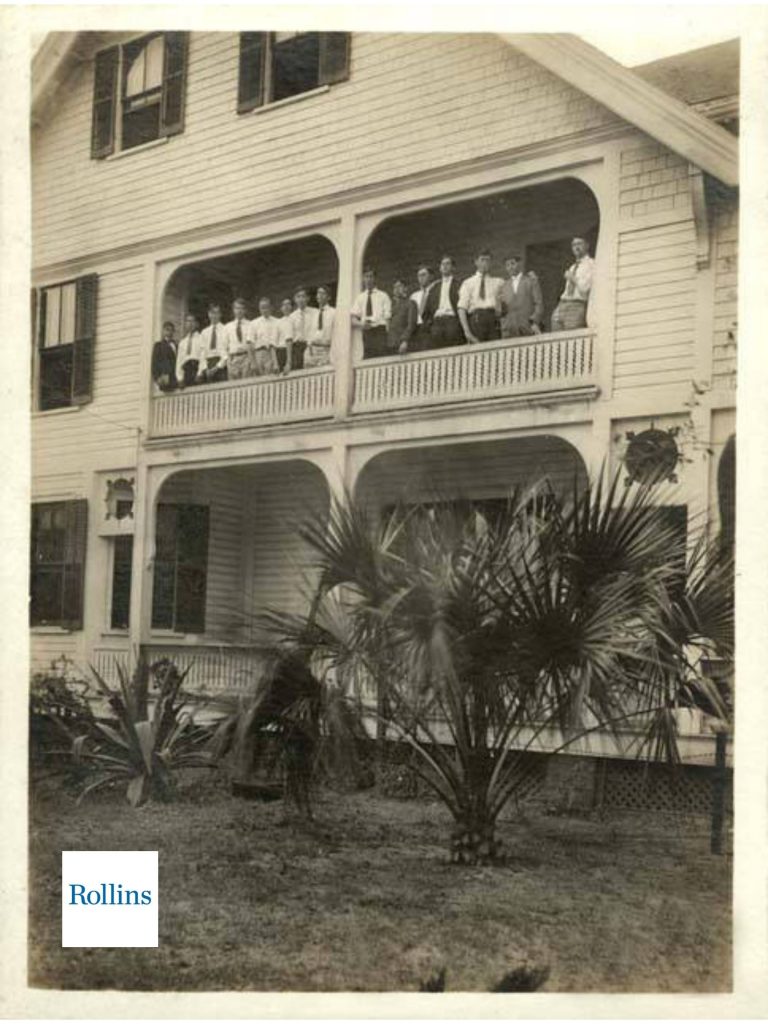

Thus, by design, Lady Pinehurst mirrored an upper middle class New England domestic dwelling. Architecturally, she was (is) a fine example of an early form of the American Queen Anne house style, built at a time when the design still possessed an elegant simplicity. Its characteristics included an oft-center dominant gable, with over-hanging eaves, three smaller gables placed symmetrically along the front roof and an asymmetrical front facade. But the most significant attribute of this style was its two porches, a ground floor wrap-around front porch and a second-floor side porch resembling a balcony. Very early, Lady Pinehurst’s spacious front porches became the venue for the college’s social interactions, and for good reason. Front porches were an essential aspect of Victorian culture.

Architectural historians have shown us that the style of domestic dwellings we build are statements about the kind of personal and social life we expect to live. During the century Victorian era, front porches, some of which wrapped around the entire front of the house, were considered an essential part of a home. Front porches were liminal spaces; they occupied a threshold between the private inside and the public outside of a home. The interior was a kind of haven from the outside world, and the front porch provided a way of interacting with the wider community. Victorians and early twentieth century Americans considered these spaces essential to a full life. As one writer has noted, the porch in that era was as a “platform from which to observe the activities of others. It also facilitated and symbolized a set of social relationships and the strong bond of community feeling….”

That was the key to the meaning of the front porch—that community life was just as important as the private one. The front porch advertised, both a visually and actually, a family’s commitment to participate in its community. The porch’s “communal nature called attention to the relationship between family and society,” fusing the private and the public worlds, one writer observed. Lady Pinehurst’s porches served the same purpose as they did in Victorian homes, that is, as a venue for students and faculty engagement in campus life.

The 1909 fire, which consumed Knowles, almost laid waste to the Grand Old Lady.

It damaged the north-side of Lady Pinehurst and, in the process of making repairs, the college enclosed that side of the first-floor porch and the second-floor balcony. This left Lady Pinehurst with a diminished front porch, but it was enough to retain its appeal. It remains one of her most treasured features.

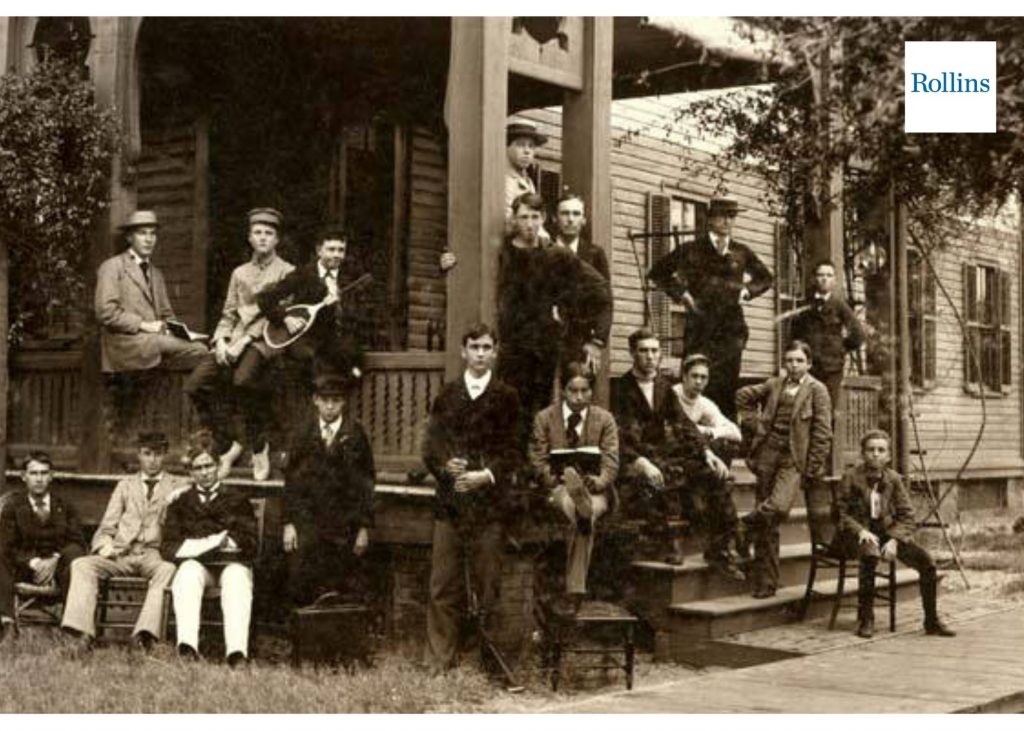

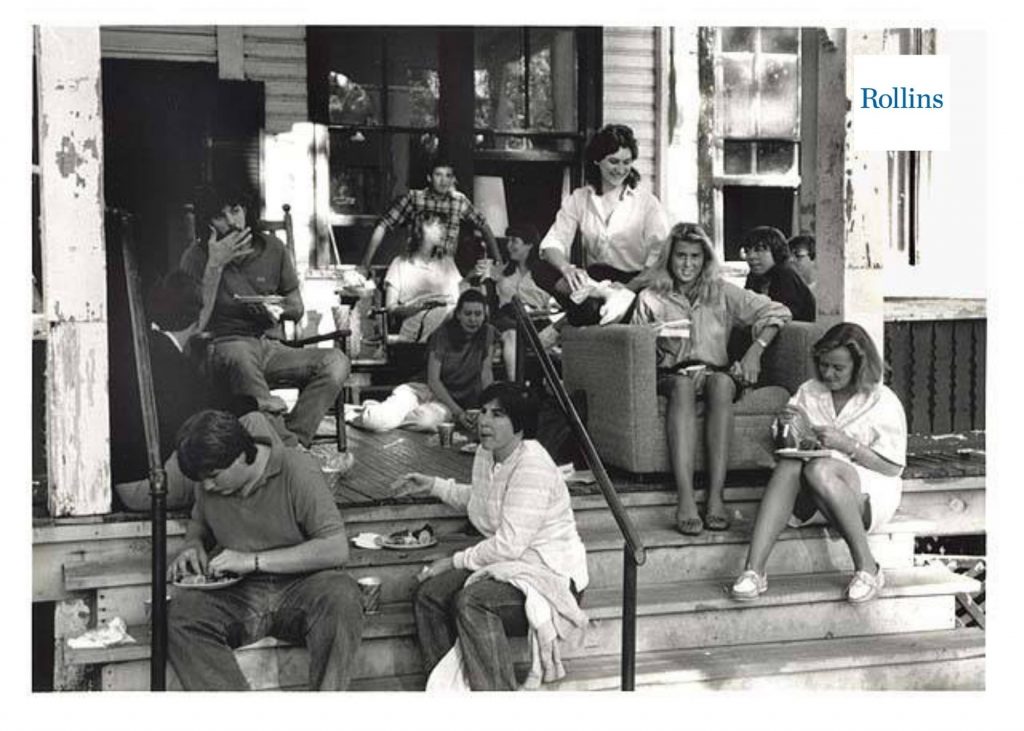

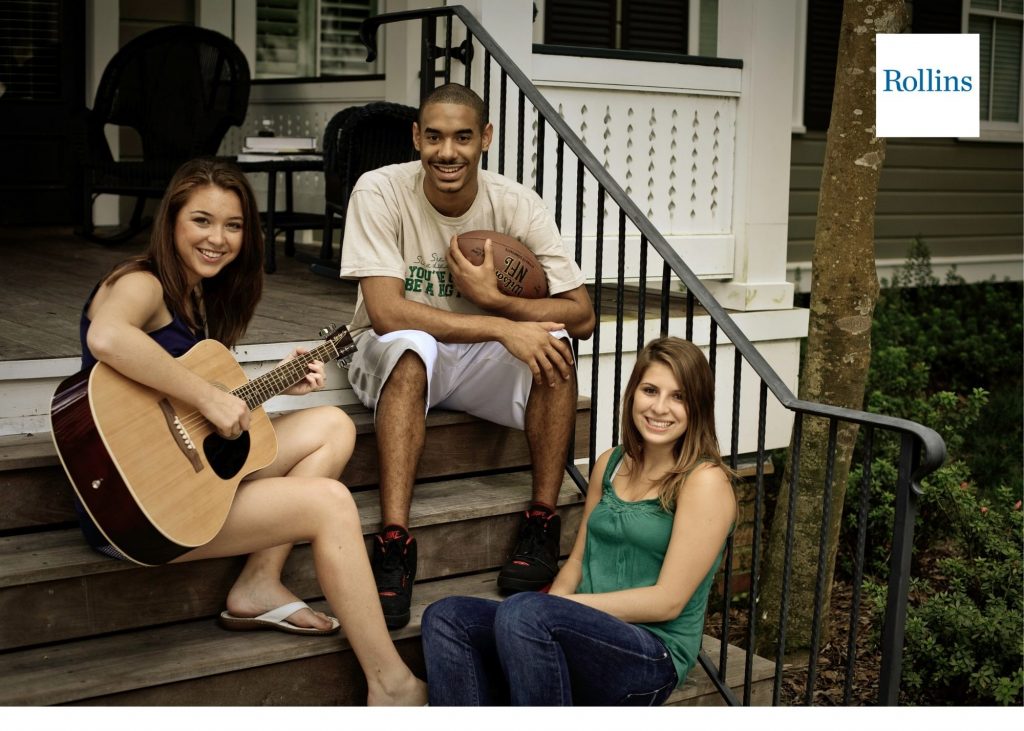

Perhaps the best evidence of Lady Pinehurst’s porch’s appeal is its popularity as a venue for photographs. Below is a chronological collection of these events.

Over the decades, Lady Pinehurst willingly served whatever demands have been asked of her. Six years after her dedication, the college constructed Cloverleaf which became the home of Rollins women and from that time on, the Lady was called upon to serve a whole host of purposes—as a Music Conservatory, as home to the English Department, as a Post Office, as College Relations office, as the headquarters for a military unit called Specialized Training and Reassignment during World War II and as a home of the Latin Studies Program. Finally, in the 1960s Lady Pinehurst was asked to return to her original purpose: she became a dormitory housing. First a sorority and, in the 1980s, a co-ed living facility, a situation that would have shocked her Victorian creators beyond belief.

All these demands and activities had an effect on Lady Pinehurst’s health. Except for a new roof in 1950, over the years suffered the burdens of “deferred maintenance.” But as the college’s centennial neared, President Thaddeus Seymour decided to undertake a major renovation and in 1985 he employed a preservationist expert who restored Lady Pinehurst to her original design. Today she stands proudly as a visual reminder of continuity between those early Victorian years and the present.