Last week I wrote about research I have been doing on two recent acquisitions in CFAM’s Alfond Collection. This week, I’d like to continue with American photographer Andrew Moore’s 2016 Pitt’s Folly, Perry County, AL, from the recent series Blue Alabama.1 This is the fourth photograph by Moore in the collection, three of which I will examine today. Compared with earlier pieces, Campo Amor (Vista Este), Havana, Cuba and School District 123, Cherry County, Nebraksa, this latest acquisition speaks to a potential new direction in Andrew Moore’s work. I suspect this may be in response to recent scholarly and critical writing on the artist.

Let’s start with the earliest image of the three. Moore first came to prominence for his large-format, color photographs of ruined buildings—in particular theaters—in post-Soviet Russia and Cuba.2 Campo Amor is a prime example. The theater has lost all of its former grandeur, and now serves as a parking area for pedicabs, which cluster at the foreground of the image while the vaults of the ceiling soar overhead. Despite the ruin, the scene is quite beautiful. The utilitarian vehicles provide pops of color contrasting with the bronzy earth tones of the building. Notably, the arches to either side of the ceiling are covered in greenish algae or moss, and weeds poke up through the concrete floor. Amidst the decay, there is a sense that nature is reclaiming this space that once belonged to humankind. This is a key aspect of Moore’s work, which frequently features a redemptive sense of nature taking back places that have been only temporarily occupied by humanity.3

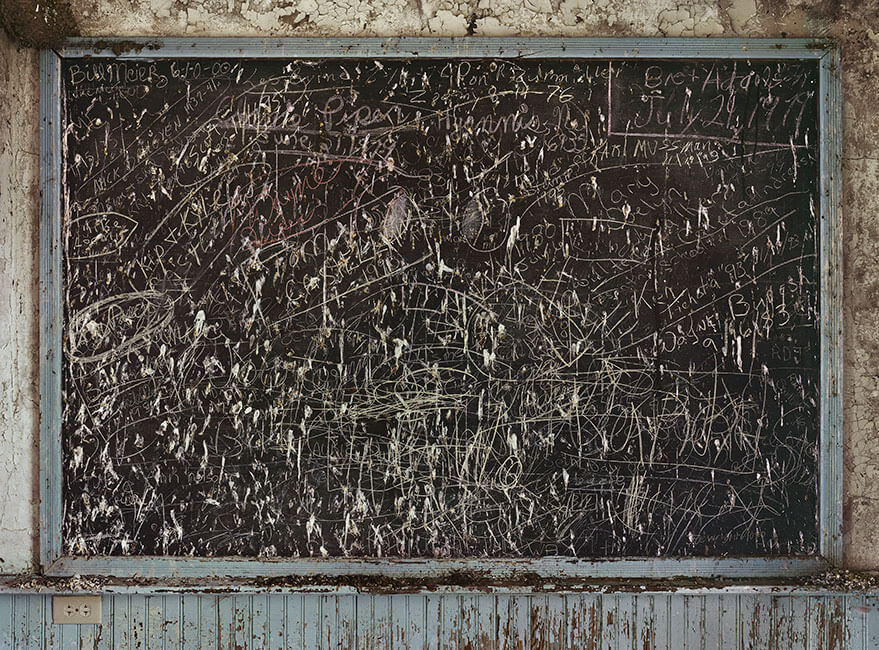

In the twenty-first century, Moore has increasingly turned his eye for beautiful ruins to the United States, perhaps most famously in a series of images of Detroit. Featuring decrepit buildings from the formerly vibrant industrial city, these images translate his aesthetic—which owes a great deal to nineteenth century painters of the sublime like Caspar David Friedrich and Frederic Edwin Church—closer to home. CFAM does not own one of the Detroit images, but the slightly later School District 123, Cherry County, Nebraska is similar in many ways. The photograph is dominated by a chalkboard at an abandoned school, still covered in scribblings, one of which reads “July 24, 1979,” suggesting that the school was abandoned quickly and then lay dormant for over forty years before Moore came to photograph it. These scribblings, as well as the peeling paint and cracking walls, are poignant reminders of the absent human presence.

For a number of scholars and critics, including Dora Apel, Tim Strangleman, and Kyle Chayka, Moore’s decision to photograph Detroit cast his practice in an unsavory light. Grouping him with other photographers who made images of abandoned Detroit buildings, these writers and others criticize this work as “ruin porn” which creates aesthetic objects out of the decaying fabric of American life. Noting that Detroit’s decline has a specific racial dimension, they question the decision to exclude the remaining residents of the city from view (Detroit’s population is over 700,000), rendering beauty out of an ongoing human tragedy.4 The scholar Miles Orvell, while noting the discomfort that such images can cause, recasts the debate somewhat, arguing that Moore is actually engaged in the creation of a new visual category, which Orvell calls the destructive sublime. The sublime has a long history in Western art. It refers to images which, through their sheer visual impact, evoke a feeling of wonder, a sense of the awesome power of God—or nature—and the relative insignificance of an individual person. In Orvell’s formulation, the great power of Moore’s work is in its evocation of this feeling, the ways in which it evokes both moral revulsion as articulated in “ruin porn” criticism and more aesthetic senses of beauty and grandeur.5

School District 123 comes from a series Moore calls Dirt Meridian, which consists of photographs taken in the area usually known as the Great American Desert—roughly the Western part of the Great Plains.6 That brings us back to Pitts’ Folly, which is one of many images the artist made in Alabama’s Black Belt, so named because of its rich soil as well as the unique African American culture of the region.7 The photograph depicts the Greek Revival portico of an old house, which seems to be in the early stages of the kind of decline Moore has long depicted. The woods run right up to the porch itself, and weeds have begun to peek through cracks in the wooden walls and pillars of the structure. It may or may not be abandoned—a potted plant and plastic watering can suggest that someone is still caring for the place—but it seems well on its way. Importantly, Pitts’ Folly is not just any house. It was built in the 1850s to stand at the center of a cotton plantation, making it one of the foremost sites of American slavery. To my mind, the stakes of the potential abandonment of such a place are different than a once-thriving city like Detroit, or the hollowing of a small town in Nebraska. Pitts’ Folly is a place of pain, built on the torture and enslavement of dozens of people. To see it fall into ruin would, perhaps, allow for all the aesthetic pleasures brought by Moore’s earlier work, but without the ambivalent feelings they also call forth.

Writing about Blue Alabama, Moore says that for him it exists in a continuity with Detroit Disassembled and Dirt Meridian, remarking “Whether by chance or instinct, I’ve always been drawn to places that seem to be on the verge of change, especially when the fibers of culture, politics, and history ripen into a form unique to that particular place.”8 In looking at the photographs themselves, however, I can’t help but wonder how Moore has been affected by criticisms that he creates “ruin porn.” I have not seen him address these critiques directly, but both Dirt Meridian and Blue Alabama contain many more images of people, and not just people integrated into the scenery but actual portraits, showing named individuals posing singly or in small groups. There are still pictures of abandoned and crumbling architectural spaces in Blue Alabama, and they are still as crushingly, hauntingly beautiful as the works in CFAM’s collection. But Moore also seems—consciously or not—to be inviting more humanity into his work. I, for one, could never see Blue Alabama as ruin porn, and to my eye it keeps the best features of his early work while evolving into something even more striking and powerful.

3Apel, 88–89.

4Dora Apel, “Ruin Terrors and Pleasures,” in Beautiful Terrible Ruins, Detroit and the Anxiety of Decline (Rutgers University Press, 2015), 12–26. “Detroit Ruin Porn and the Fetish for Decay,” Hyperallergic, January 13, 2011. Tim Strangleman, “‘Smokestack Nostalgia,’ ‘Ruin Porn’ or Working-Class Obituary: The Role and Meaning of Deindustrial Representation,” International Labor and Working-Class History, no. 84 (2013): 23–37. For a sense of Moore’s work in Detroit, see his website.

5 Miles Orvell, “Photographing Disaster: Urban Ruins and the Destructive Sublime,” Amerikastudien / American Studies 58, no. 4 (2013): 652–54.