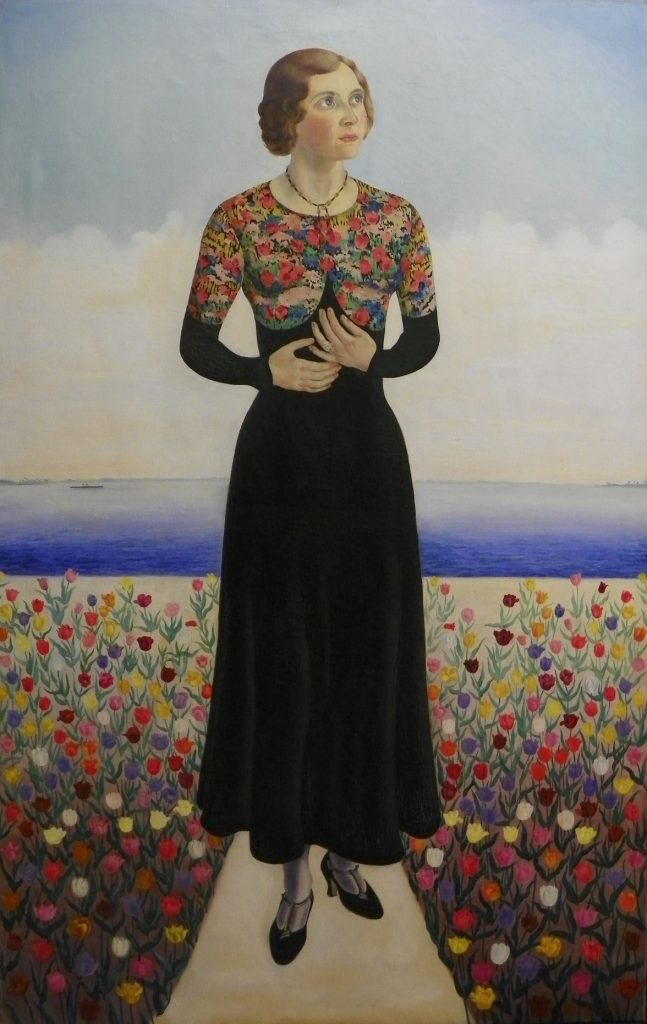

Allegorical Portrait of Ellen Pataky

1931

Oil on canvas

60 x 38 in.

Gift of Mrs. Tibor Pataky, 1985.14

For me, one of the great pleasures of museum work is getting to know an individual collection. At institutions like CFAM, which are tied to specific communities of alumni, donors, students, faculty, and local visitors, collections grow organically, reflecting the interests of all the people who make a community like Rollins and Winter Park special. At CFAM, we are fortunate to include 217 works by the Hungarian-American painter Tibor Pataky in the collection, a result of a generous gift by his widow, Ellen, in 1985. Born in Budapest, then one of the two capitals of the Austro-Hungarian Empire, Pataky was trained at the Royal Academy there, eventually becoming an instructor.1 In 1929, he was in Paris to study, when he happened to meet an American visitor named Ellen Swayne. Though she spoke no Hungarian and he spoke no English, they carried on a two-year courtship via letters, which were translated by relatives. In 1931 Pataky moved to Florida, leaving behind his comfortable life as an art professor to marry Ellen. Rural Central Florida must have been quite a change for the cosmopolitan Pataky, and the couple supported themselves at least in part with the income from an orange grove.2 By the 1936-37 school year, he was a professor at Florida Southern in Lakeland, where he would spend the rest of his teaching career, though he also directed the Center Street Gallery in Winter Park.3

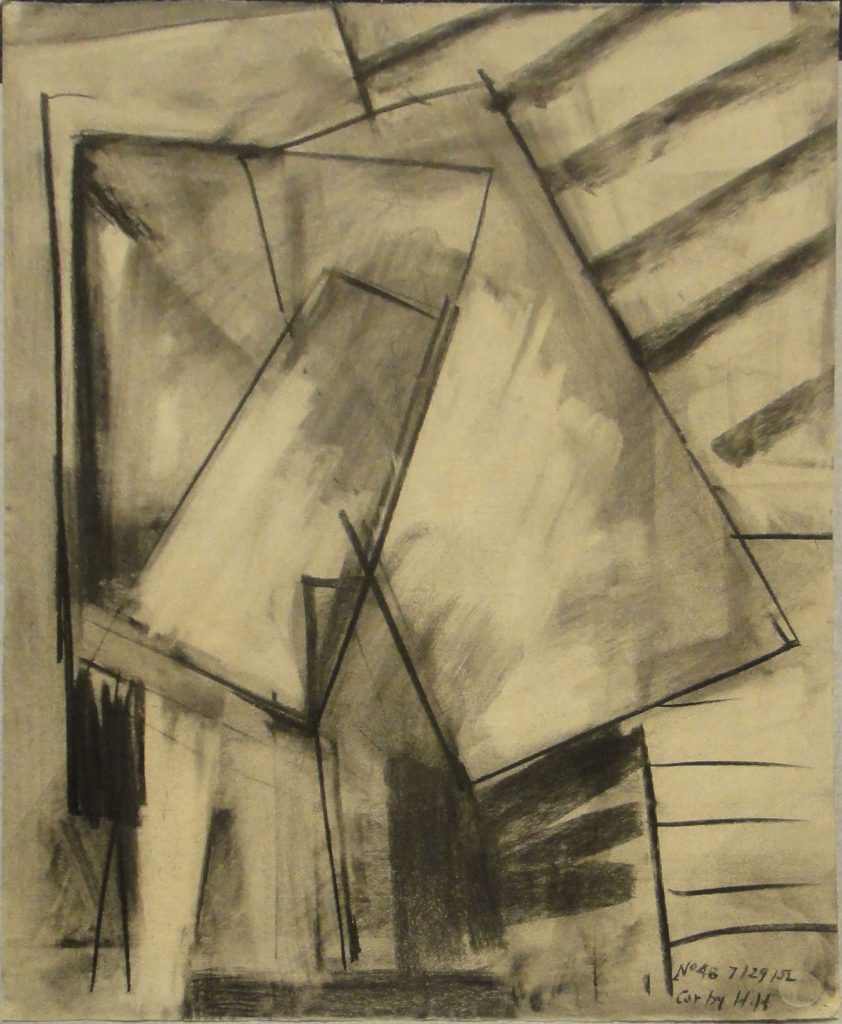

Diagonal Block Study

1952

Charcoal on paper

25 x 19 in.

Gift of Mrs. Tibor Pataky, 1985.31.23

Allegorical Portrait of Ellen Pataky, one of the works in the CFAM collection, dates from his first year in Florida. It is a fine example of Pataky’s early style, which used an expressive realism to capture the lives of Hungarian—and later Mexican—peasants.4 The painting depicts Ellen as a rosy-cheeked beauty proudly displaying her wedding ring while she gazes dreamily into the sky. She stands on a white Florida beach, the deep blue water of the ocean, Gulf, or perhaps Tampa Bay spreading out to the low horizon behind her. She is surrounded, curiously, by a field of tulips, a European flower that does not grow in Florida (the bulbs require freezing winter temperatures to develop properly). In addition to Pataky’s obvious love for his wife, whose floral print top unifies her visually with the flowers, the painting seems to show him making sense of his new surroundings, incorporating them into the more familiar visual world of his Central European home.

Pataky would go on to achieve regional and national renown for his depictions of daily life, exhibiting frequently at the All-Southern Art Association; at galleries in Boston, New York, and San Francisco; and even in the American Pavilion at the 1939 New York World’s Fair.5 In 1952, however, his career took on a sudden new direction, as he fell under the influence of German émigré Hans Hoffman, who had established a summer art colony in Provincetown on Cape Cod in Massachusetts. Hoffman, who had come to the United States in 1932, was a huge influence on the American art world’s turn to abstraction in the 1940s and 1950s.6 Pataky quickly adopted Hoffman’s abstract style, as a 1952 drawing (really more of a student exercise), entitled Diagonal Block Study, shows. Pataky has replaced the lyrical realism of his earlier work with a spare linearity, working out the relations of pure rectangular forms with a series of bold and decisive strokes of his charcoal. Writing in the lower right indicates that it is from his first summer with Hoffman, who has left a note indicating he has reviewed the exercise.

Untitled

1960

Oil on canvas

23 ¼ x 19 in.

Gift of Mrs. Tibor, 1985.13

These exercises would result in a new style in Pataky’s finished paintings, as well. Untitled, signed “Tibor ‘60” in the lower left, is one of the best examples in the collection. Compared to the riot of color seen in Allegorical Portrait of Ellen Pataky this painting is downright severe, using only shades of gray and yellow, as well as a few patches of pure white, to present an abstract vision of rectangular forms held in dynamic tension with one another. Whether you prefer his earlier Regionalist-inflected realism or his spare late abstractions, Tibor Pataky presents a fascinating case of a local artist who followed the wider trends of American art in the middle of the twentieth century. We are fortunate to have such a rich collection of his work here at the Cornell Fine Arts Museum.

1Most of my information about Pataky’s biography comes from the Tibor Pataky Papers. Florida Southern College Archives.

2Bishop, Phillip E. “The Paintings of Tibor Pataky.” 3The Orlando Sentinel July 22, 2001.

4A copy of Pataky’s CV is found in the Florida Southern archives.

5“Hungarian Depicts Mexico.” The Art Digest. (April 1, 1936), 15.

6Pataky CV, Tibor Pataky Papers, Florida Southern Archives.

Bishop, Phillip E. “The Paintings of Tibor Pataky.” The Orlando Sentinel July 22, 2001.

Thanks for this illuminating account of Tibor Pataky’s life and artistic development. I would be interested in knowing more about how his focus on Hungarian peasants widened to include Mexican peasants. (A portrait of a Mexican peasant hangs, discretely, on a wall of our house) And, was the shift form lyrical realism to abstraction really that sudden? Is there anything in the earlier phase of his work that presaged his later output? What was that Hans Hoffman tapped into?

I look forward to meeting you when, the virus crisis over, you join us in Winter Park

Thank you for your comment! These are really great questions – hopefully things will calm down a bit and we can discuss them in person in Winter Park. For now, though, I have some preliminary thoughts. Art in North America in the 1930s was, in general, quite concerned with peasants. Or, since we are unaccustomed to speaking about people in the United States as peasants, we might expand/shift the term ‘peasant’ to something like ‘rural working class’ or even ‘country folks.’ As an art lover, you are likely familiar with the set of discourses in American art that are often called Regionalism. Painters like John Steuart Curry, Thomas Hart Benton, and Grant Wood are well-known today for their representations of rural American life. Curry was from Kansas, Benton from Missouri, and Wood from Iowa, and they all took subjects from the Midwest as key parts of their artistic practice. If you look at Pataky’s portrait of his wife Ellen above, you’ll see certain aesthetic similarities to, say, Grant Wood’s ‘Parson Weems’ Fable’ (https://www.cartermuseum.org/collection/parson-weems-fable). Wood’s work has more of a satirical edge than Pataky (especially in this portrait of his wife), but they share a certain iconic and monumental style, one which demonstrates an economy of line and a preference for broad, bright expanses of landscape coupled with a relative simplicity of representing the human form. Pataky’s work depicting Mexican peasants is similar in many respects.

Even more importantly, however, is that there were a large number of Mexican painters working in similar styles, many of whom depicted Mexican agricultural and industrial laborers. The most famous of these are Frieda Kahlo and her husband Diego Rivera, but there were many more. Pataky’s gallery representation in New York was for many years handled by Delphic Studios, which was the representative for a number of these Mexican modernists, most notably José Clemente Orozco. Now, information that I don’t have (but sure wish I did) is whether Pataky got into Mexican subjects because of his affiliation with Delphic, or if it was the other way around, i.e. when he was visiting Delphic perhaps he saw Orozco or another artist’s work on the walls and was inspired. Since documentation of his life and career are so sparse, we may never know. But it was very common for artists to travel from America to Mexico in search of subjects, largely based on their interest in Mexican modernist painters as well as on indigenous Mexican art. Mexico City was undergoing rapid expansion in the 1920s and 1930s, and all that construction was unearthing all sorts of treasures, many of which ended up on the art and antiquities market in Mexico City as well as in New York. Another pair of well-known European expatriates who were very interested in Mexican art (and were friends with Rivera) were Josef and Anni Albers, who made many trips from New Haven, Connecticut to Mexico while they were at Yale.

So that’s all a kind of roundabout way of saying that we don’t know for sure, but Mexico was a major source of imagery for modern artists in the 1930s, as were rural scenes more generally. Since Pataky had already shown such an interest, and likely knew some of these same folks from his art world activities, it was a natural fit. Plus, as anyone who has ever taken a Mexican vacation will tell you, it’s a great place to visit!

As for the question of his shift to abstraction, that’s a really good one as well. By way of answering it, I’d like to mention again Thomas Hart Benton. Benton was well known for his monumental depictions of Missouri life and history (along with his incredibly cantankerous personality), but there is one more thing he’s known for: he was an early teacher of Jackson Pollock, almost certainly the most famous American abstract painter. Pollock, under Benton’s tutelage, actually started out working in a figurative vein (https://www.moma.org/collection/works/78719) before transitioning to full abstraction in the late 1940s. And while Pollock never studied with Hans Hoffman, a large number of American painters did, first at the Art Students League and later at his private painting schools (including the one Pataky studied at in the early 1950s). One of those was even Lee Krasner, who was an abstract painter as well as Pollock’s widow. Art historians have generally regarded Hoffman as one of the foundational influences on the development of Abstract Expressionism, and by shifting to that style in the 1950s Pataky would have been moving with the mainstream of the American art world.

You mentioned whether there was any stylistic hint of this coming change – I would point to the flat landscape in the portrait of Ellen as one possibility. While that is clearly a vision of a Florida beach, it also is significantly abstract, with flat bands of color laid one on top of another, almost like the paintings of Mark Rothko (https://www.moma.org/collection/works/80566?sov_referrer=artist&artist_id=5047&page=1). These flat, abstract qualities of 1930s art definitely contributed to the dominance of a flat, non-representational sense of space in Abstract Expressionism.

Thanks again for your questions–Pataky is such a fascinating figure, and I appreciate the opportunity to think some more about him!