In my research into the CFAM American collection, I have been moving more-or-less alphabetically by century, with occasional detours to consider specific objects and themes that interest me. That means my day-to-day experience is somewhat eclectic, jumping around in terms of time, subject matter, and other ways artists are usually categorized. Occasionally, however, this process reveals moments of serendipity, in which two artists who are close to one another in my alphabetical list—but otherwise unrelated—reveal heretofore unseen affinities. This was especially notable this week, as I considered the work of two seemingly very different artists, Joseph Cornell and Earl Cunningham. Though they were born within ten years of one another, the two artists worked in very different styles and traveled in very different circles. Neither artist was formally trained, and both were somewhat reclusive, even odd. In addition, both were keenly observant of the world around them, a trait that each man demonstrated through his careful and even obsessive collecting habits. And yet, as we shall see, the two artists created vastly different bodies of work.

Earl Cunningham lived an eventful life. Born in Maine, he left school as a teenager to work as an itinerant peddler and laborer, eventually joining the Merchant Marine, working on ships that moved lumber and other commodities along the East Coast from Maine to Florida and back. He also worked as a yacht pilot, a chicken farmer, and a truck driver before settling down in St. Augustine, Florida in 1949, where he opened a combination antique store and gallery called the Over-Fork Gallery.1 An irascible and irritable man, Cunningham obsessively organized his antique shop, which included local pieces as well as American Indian pottery, in particular from the Mound Builders of the South and Central United States.2 Next door to the antique shop were his paintings, which he was careful to inform interested inquirers were not for sale. Intending to create a thousand paintings during his life (he died with over 600 completed), Cunningham only sold a painting when compelled by financial necessity, and the vast majority of the works remained in his gallery upon his death in 1977.3

Oil on Masonite, 16 x 20 in., Gift of Mr. and Mrs. Thomas Yochum 2015.24

In addition to collecting antiques for sale and his paintings themselves, Cunningham collected visual materials, both literally and more figuratively. His works were executed with mixtures of commercial and artistic paints, many of which he purchased in junk shops and at yard sales. He also repeated the same visual motifs throughout many of his works, including schooners, covered bridges, lighthouses, horse-drawn carriages, Vikings, the Seminoles of Florida, lighthouses, birds, and Maine. These themes, drawn from a mixture of commercial illustrations, fine art, and his own lived experiences, are perhaps Cunningham’s greatest form of collecting.4 Canal With Water Hyacinth is a perfect example of this process, combining Cunningham’s luminous, almost enamel-like sense of the colored surface with small human figures—probably Seminoles—in canoes, an old-fashioned sailing ship, and several birds in flight. It is an appreciation of Florida, in particular the Everglades, but filtered through Cunningham’s unique life story and interests.

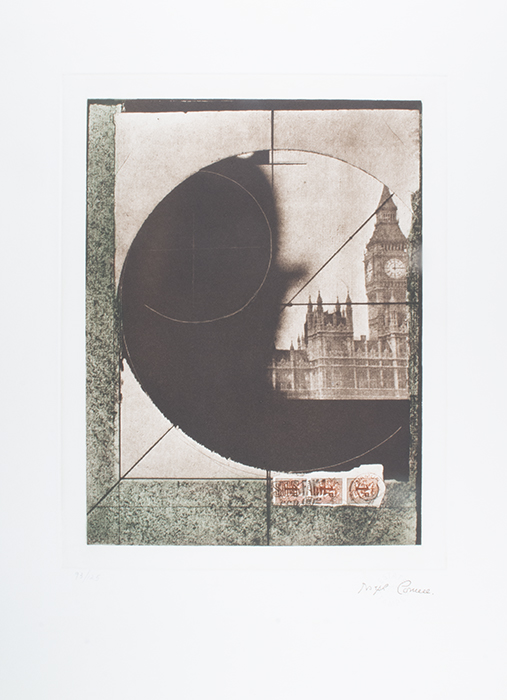

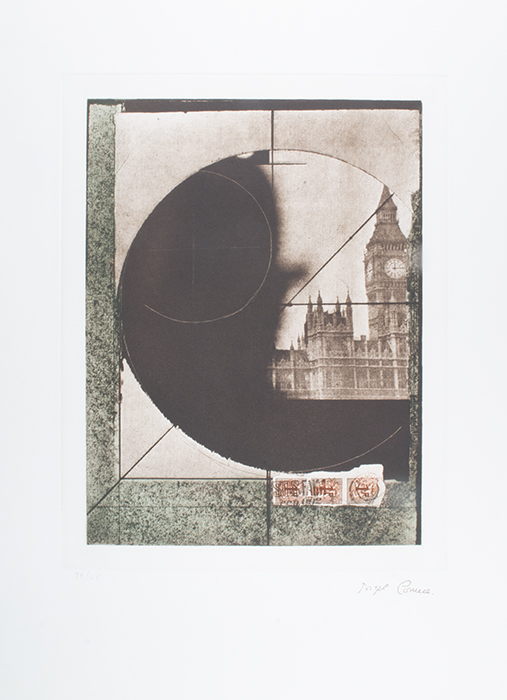

Another American artist whose unique life story and interests informed his work is Joseph Cornell. Born on Long Island, he moved to Queens with his family as a child and essentially never left, spending decades roaming New York, first as a fabric salesman and then as a working artist, stopping in at junk shops and other out-of-the-way places, accumulating a vast trove of printed material and small items. He kept all of this material meticulously organized in the basement of the Flushing home he shared with his mother and brother, using it to create his wondrously strange and inventive collages and assemblages.5 The surviving material has been organized and made available for use at the Joseph Cornell Study Center at the Smithsonian American Art Museum in Washington, D.C.. Like Cunningham, Cornell created works that spoke to his interests, including time, space, archival thinking, classification, and the relationships between individuals and types.6 Unlike Cunningham, however, Cornell lived and worked in New York City, and his meticulously constructed works spoke to many of the same themes and used many of the same methods as the avant-gardes of the 1930s, most notably the Surrealists. In fact, he was frequently exhibited with Surrealists in New York, and may have been influenced by the work of Max Ernst and others he saw at Manhattan galleries.7

(American, 1903-1972)

Untitled (Derby Hat), 1972

Heliogravure

13 ¼ in x 10 ¼ in. Print

Purchased by the Wally Findlay Acquisitions Fund. 1993.3

© The Joseph and Robert Cornell Memorial Foundation/ Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York, NY

In Untitled (Derby Hat) we see a rare print by Cornell, who adapted his collage technique to heliogravure, an early technology that allowed the reproduction of photographic prints. The print was made to benefit the Phoenix House, a drug treatment program. Brooke Alexander, the art dealer who produced the portfolio, acted as Cornell’s go-between, taking collages from Cornell’s house on Utopia Parkway in Flushing to a printer’s studio.8 Though he was new to printmaking, the elderly Cornell (in the last year of his life when he made the work), adapts to it quite readily, incorporating signature elements, including found printed material, geometric elements, and enigmatic circles which evoke astronomy and outer space. The work is a meditation on the nature of time, both historical and natural, as well as a wonderful demonstration of Cornell’s collecting interests. The nearly monochromatic work is a far cry from the bright color of Canal With Water Hyacinth, and represents a very different artistic and personal sensibility. Despite the fact that both artists were essentially untrained, their practices informed by idiosyncratic collections, they have produced very different works indeed.

1 FRANK HOLT, “Cunningham, Earl,” in The New Encyclopedia of Southern Culture, ed. CAROL CROWN and CHERYL RIVERS, Volume 23: Folk Art (University of North Carolina Press, 2013), 254. For a definitive overview of Cunningham’s life and work see Earl Cunningham et al., Earl Cunningham’s America (Washington, D.C: Smithsonian American Art Museum, 2007).

2 Robert Carleton Hobbs and Earl Cunningham, Earl Cunningham: Painting an American Eden (New York, N.Y: H.N. Abrams, 1994), 55.

3 Hobbs and Cunningham, 20. The vast majority of them are now at the Mennello Museum of American Art in Orlando.

4 Hobbs and Cunningham, 13, 35–40. The majority of Cunningham et al., Earl Cunningham’s America. Considers this subject matter, with chapter/section titles drawn from these and other themes.

6 Cornell and Hartigan, Joseph Cornell, 15, 335.

7 For more on Cornell’s complex relationship to Surrealism, see Joseph Cornell, Matthew Affron, and Sylvie Lecoq-Ramond, eds., Joseph Cornell and Surrealism (Charlottesville, Virginia: The Fralin Museum of Art at the University of Virginia, 2015). It remains somewhat unclear whether Cornell had started making collages before he encountered the work of the Surrealists or if he was inspired directly by them.

8 Deborah Solomon, Utopia Parkway: The Life and Work of Joseph Cornell (New York: Other Press, 2015), unpag.