I was inspired to write this post after enjoying a recent CFAM Work of the Week: Derricks at Night by the American printmaker Martin Lewis. In her introduction of the print Curator Gisela Carbonell relates Lewis’s relationship with the work of his fellow artist Edward Hopper, with whom he shares an affinity for the obscure nighttime activities of New York’s anonymous urban dwellers. Having run across the stories of the two men’s association in my own research, I share Dr. Carbonell’s sense that, whether the stories are true or not, the parallels are striking. For myself, in addition to Hopper, my work on Lewis immediately made me think of another American printmaker: James Whistler. I wrote about Whistler back in April, as part of an appreciation of the strength of CFAM’s collection of modern etchings.

Scholars have long considered Whistler—along with his brother-in-law Seymour Haden—one of the progenitors of the so-called “etching revival” of the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, as I wrote about in the April blog post.1 Lewis, for his part, stands nearly at the other end of that revival. He came of age as a printmaker around 1920, establishing himself as a prolific artist in etching—as well as drypoint (a type of engraving), lithography, and several other mediums—well into the 1940s. The Great Depression took a toll on his sales, and his advancing age further reduced his output.2 By 1953, when he made his last recorded print, American artists were increasingly turning to the medium of lithography, which allowed for the spontaneous application of line and color favored by Abstract Expressionists.3 Lewis was, in many ways, one of the last of the artist-printmakers, and CFAM is lucky to include several of his works in the collection.

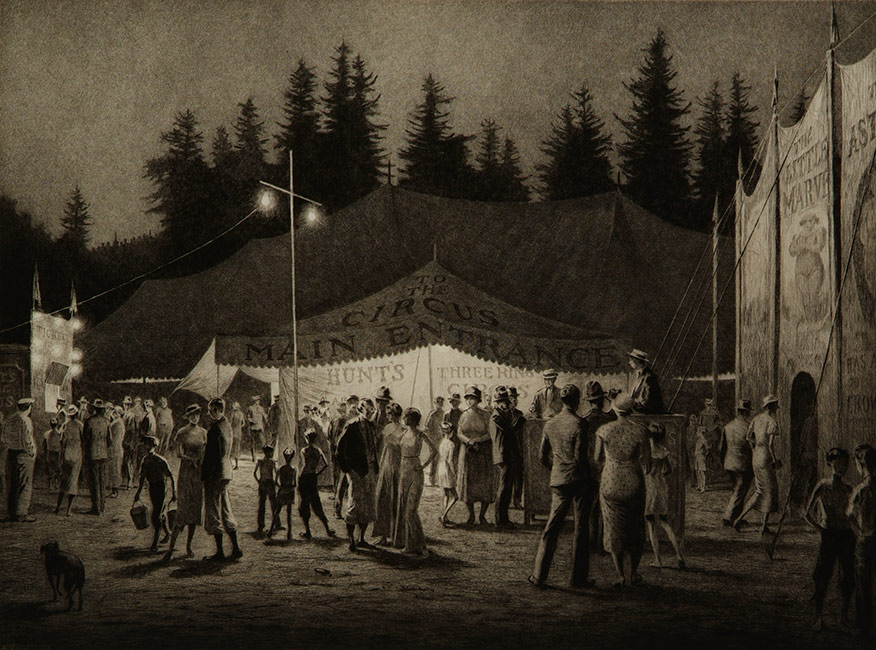

Interestingly, all six of the prints in the collection are drypoint, rather than etching. As I mentioned above, drypoint is a kind of engraving that uses a very fine needle to achieve precise effects of detail. With drypoint, an artist incises lines directly into the polished copper plate. This is contrasted with etching, in which the artist carefully scrapes away a pre-applied layer of wax before dipping the plate in a bath of acid in a process known as biting. The differences between the two media are relatively subtle, and both allowed Lewis to take advantage of his strong ability as a draftsman. In addition, some of the prints—including Circus Night—include an additional technique, called sand ground. In this technique the artist applies the wax coating for etching, then using sandpaper, emery board, or loose sand to make a series of pits in the wax. Upon biting, the plate achieves a soft, hazy effect that Lewis vastly preferred to the sharp, shiny copper of pure etching or engraving.4

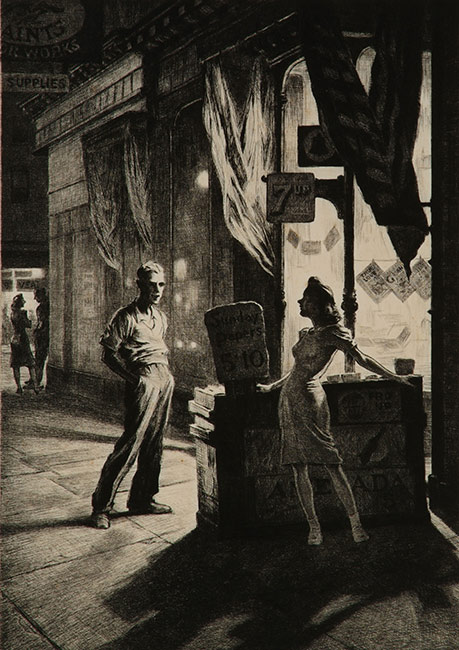

1940-1, Drypoint, 15 1/2 x 10 5/8 in., Gift of Mrs. Helen Pratt,1981.9.13

The collection also includes Chance Meeting, a relatively late print that Paul McCarron, an expert on Lewis who compiled a catalogue raisonné of his work, called his most complex composition, as well as one of his last notable ones.5 Commissioned by the Society of American Etchers, it is, like Derricks at Night, a demonstration of Lewis’s absolute mastery of tonal range. The light from a five-and-dime spills out onto the street, illuminating a chance encounter between two young people in front of the store. The light throws the young man into harsh illumination, which is translated by the deep shadow on the far side of his body. The young woman leans seductively against a display, though it is unclear what, exactly, either of them is up to. The scene carries an aura of mystery, and perhaps of menace. This aura of latent fear or suspense has led some scholars to link Lewis’s work to the film noir genre, though more in terms of the genre’s atmospheric effects than its stories, which tend to center on murder and psychological dread.6 Beyond those connections, this print helps to illuminate another side of Lewis’s work, which is his sensitivity to the mundane social interactions that color so much of modern urban life. Lewis complained frequently about New York but seems to have been unhappy living anywhere else. His inspiration for his most powerful prints, including both Derricks at Night and Chance Encounter, came from the city, in particular the way its inhabitants navigate both its urban spaces and each other.7 This aspect—along with his technical and formal mastery—lend the prints a timeless quality that makes them speak to us today just as much as they did to the world of a hundred years ago.

1 For an excellent overview of the etching revival, see: Elizabeth K. Helsinger and David and Alfred Smart Museum of Art, eds., The “Writing” of Modern Life: The Etching Revival in France, Britain, and the U.S., 1850-1940 (Chicago, Ill: Smart Museum of Art, University of Chicago, 2008).

2 Paul McCarron and Martin Lewis, The Prints of Martin Lewis: A Catalogue Raisonné (Bronxville, N.Y: M. Hausberg, 1995), 18–21.

3 McCarron and Lewis, 27.

4 McCarron and Lewis, 18–19.

5 McCarron and Lewis, 21, 25, 222.

6 McCarron and Lewis, 25–26.

7 McCarron and Lewis, 14, 27.