by Nancy Chick, Kent Andersen, Stephanie Rolph,

Betsy Sandlin, & Linda Boland

This spring’s abrupt shift to remote instruction is forcing colleges and universities to grapple with the specific value of each institution’s educational environment (Lederman, 2020). Universally, campuses were forced to take up fully remote forms of teaching and learning in order to finish the term, provide continuity for students’ academic progress, and ensure students would graduate on time. Regardless of how successfully campuses met these goals, some students (and parents) claimed the remote experience “isn’t what they paid for” (see, for example, Walker, 2020 and Kerr, 2020), especially on “high-touch” campuses like small liberal arts colleges. These concerns and the subsequent apologies from administrators and faculty illuminate the need to clearly define the real value of the education offered on our campuses (Cornwell, 2020). At issue is not a question of the differences between online, remote, and face-to-face instruction. Instead, this moment is a clarion call for those of us located on these campuses to articulate what is fundamentally unique to learning at a small, residential, liberal arts college.

Some might say that it’s the liberal arts curriculum itself. That curriculum, however, is now pervasive in general education programs across institutional types. Others might say that it’s the student-centered teaching, but this is often ill-defined, and at least the claim of being student-centered is ubiquitous. We believe that the distinguishing factor is the pedagogy, or “how the visible acts of teaching are driven by what we think it means to teach and to learn” (Chick). Lee Shulman’s notion of “signature pedagogies” gives us a way to answer this question more precisely. After studying educational experiences in medical rounds in medical schools and case dialogue in law schools, he claimed that students headed toward these professions are immersed in ways of learning that “socialize” students into relevant “habits of the mind, habits of the heart, and habits of the hand” of these professions (Shulman, 2005, p. 59). Shulman challenged other fields to reflect on and become more intentional about significant learning experiences that would cultivate their distinctive habits of head, hand, and heart.

For the academic disciplines, the aim of a signature pedagogy isn’t necessarily for all students to become professionals in those fields, but instead for them to practice seeing and being in the world as biologists, historians, literary scholars, and sociologists do. Carefully developed over time and under constant reflection by practitioners, the orientation and dispositions of the different disciplines have value. This belief, in fact, is at the core of the mission of the liberal arts.

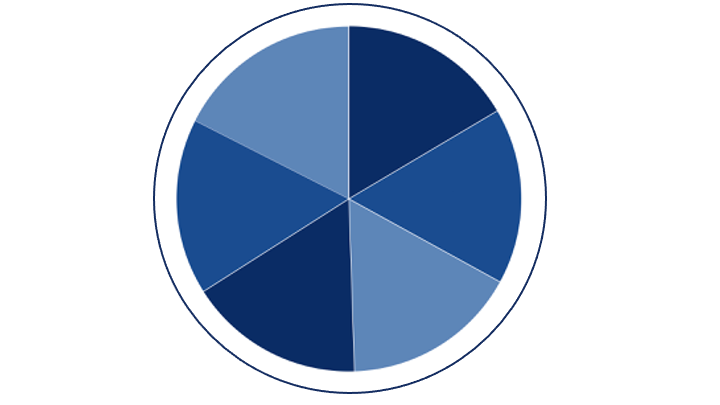

We argue that, even beyond our mission, the specific contexts of small, residential liberal arts campuses have uniquely immersive learning experiences that form the ultimate signature pedagogy of these campuses. In recent conversations with colleagues across campuses, the five of us (see right) have begun to parse what makes up these uniquely immersive learning experiences. Below, we offer our initial thoughts in mapping out precisely what teaching and learning look like on our campuses. We’ve developed a framework to illustrate that learning on the small, residential liberal arts campus happens as students develop meaningful, reflective relationships with their teachers, each other, course subjects, the broader campus, the surrounding community, and themselves–and over time, all of the above.

Nancy Chick is Director of the Endeavor Foundation Center for Faculty Development at Rollins College.

Kent Andersen is director of leadership programs in the Krulak Institute for Leadership, Experiential Learning, and Civic Engagement at Birmingham-Southern College, and serves as co-director of the June ACS Teaching & Learning Workshop.

Stephanie Rolph is Director of Experiential Learning and Strategic Initiatives at Millsaps College.

Betsy Sandlin is Associate Dean for Inclusion and Faculty Development at The University of the South (Sewanee, TN) and co-director of the ACS Summer Teaching & Learning Workshop.

Linda M. Boland is a Professor of Biology and Director of the Teaching and Scholarship Hub at the University of Richmond.

A Framework for Learning at Small, Residential Liberal Arts Institutions

Our framework is informed by Jay Wiggins and Grant McTighe’s “six facets of understanding,” which identifies ways of thinking that make up “different (though overlapping and ideally integrated) aspects of” what they call “a mature understanding” (Wiggins & McTighe, 1998; 2005, p. 84), as well as L. Dee Fink’s taxonomy of “significant learning experiences,” which are “interactive” and “synergistic” (Fink, 2003, p. 32). The complex, overlapping, integrated, mature, significant, interactive, and synergistic components in our framework are presented as relationships that students develop here. (See Figure 1.) More precisely, these relationships that students cultivate are also sites of learning created by the environment and intentional practices of the small liberal arts college.

Student-Faculty

All faculty aim to build rapport with their students. Yet, at residential liberal arts institutions, this effort translates into interactions that respond to the individual characteristics of classes and the students in them. Faculty on such campuses–partly as a result of class size but also as a result of their learned dispositions as teachers—“teach with” specific students rather than “teach to” the generic idea of students. They are attentive to students’ individual growth and development in and out of the classroom, and they know that students need different things at different moments of their matriculation.

This connection between students and faculty members has a depth that is difficult to achieve elsewhere. Students may work with some of the same faculty for their entire four years. They are also around at all hours, so faculty interact with them well beyond class time and a few formal office hours, even sharing meals together in the dining hall and living in the same buildings, as with faculty-in-residence. Their faculty teachers also serve as advisors for student government, student activist groups, and student publications. Faculty and students attend special lectures or brown-bag discussions together, and faculty attend student performances in theatre and dance and athletic competitions. Conversations with students in these varied contexts are wide-ranging, addressing challenges with course work, options for course and program selection, outside curiosities and interests, conflicts with roommates, their longer-term professional and educational goals, and, often, who they want to become.

This relationship with faculty has significant implications for students’ learning. It becomes a foundation that fosters trust and creates learning environments where students can explore new ideas, take risks, and reach beyond their abilities without fear of failure. This trust also enables students to more freely voice what they don’t understand, allowing faculty to recognize obstacles to student learning and reframe or remove those barriers. Faculty also notice a lack of engagement, a change in behavior, even subtle warning signs, and proactively connect students with relevant campus partners who are equally focused on supporting students in their time on campus. Working with students in this way encourages them to embrace the intellectual difficulties necessary for cognitive, psychosocial, and moral development.

These relationships are ongoing beyond individual classes. Students often take additional courses, choose programs, and participate in collaborative research with these faculty members. When students apply for scholarships, honorary societies, graduate schools, internships, and employment, letters of recommendation from their faculty provide personalized reflections on who they are as people–not just as students. Ultimately, faculty on small liberal arts campuses are students’ classroom teachers, their advisors, their mentors, and in some ways their neighbors.

Student-Student

In the same way that faculty and students at residential liberal arts institutions build a unique kind of rapport, students interact with each other in ways that enrich their learning experience. To be sure, most campuses require classmates to exchange ideas and feedback with their peers, and students develop friendships and join student groups on any campus. However, students at residential liberal arts institutions experience a tightly-knit learning community that’s logistically impossible at other undergraduate institutions, and available to graduate students only in a cohort model. Because our students live together in residence halls, they are roommates and neighbors, not just classmates, and certainly not strangers. These prior and ongoing relationships inform their interactions in the classroom, and how they learn with and from each other.

Because of this immersive relationship, they learn with and from each other. The nature of much of this learning is epitomized by a specific pedagogy developed at Barnard College: in Reacting to the Past (RTTP), students work closely together in weeks-long role-playing scenarios as they immerse themselves in historical moments. The choreography of RTTP isn’t what’s important here; instead, its emergence on a residential liberal arts campus and subsequent popularity on larger campuses speak to the power of the learning it harnesses.

A social network analysis of “the intensive peer interaction typical of RTTP games” showed that students’ connections with acquaintances grew even more than their friendships (see Figure 2), “provid[ing] them with intellectual challenge, thereby broadening their perspectives and guarding against groupthink,” as well as “benefit[ting] them in the years following a class as they navigate complex college environments” (Webb & Engar, 2016, p. 13). Such deep peer-to-peer engagement over time creates meaningful learning experiences in which students figure out how to work with others with differing personalities, views, and ways of being.

Such engagement starts early in the college career at residential liberal arts colleges. First-year students attend class with peers from their orientation and advising groups. Often, they get to know each other in extracurricular clubs, sports teams, Greek organizations, living-learning communities, and other courses they take together. In their study of student decision-making at residential liberal arts institutions, Lee Cuba, Nancy Jennings, Suzanne Lovett, and Joseph Swingle (2016) emphasize the importance students place on making friendships during college, as they assist students in developing critical social skills. Peer-to-peer learning becomes routine as part of the confluence of social and educational experiences, providing a sense of belonging as students encounter so much newness and spend their first years away from home.

Student-Content

Just as our campuses foster relationships among the people at the heart of students’ education, so too do we aim for students to make meaningful connections to what they’re learning. Small liberal arts institutions take great pride in their titular curriculum. By encountering a range of disciplines before settling on a major, students have ample practice to think, write, and speak through multiple disciplinary perspectives and across content boundaries. As a testament to the wisdom of this coursework, many institutions across the country have adopted a liberal arts curriculum as their general education programs. On our campuses, however, this curriculum isn’t presented as boxes to be checked through large classes that efficiently move students to the siloed courses where faculty teach their area of expertise. Students instead experience a curriculum that’s historically deep, topically wide, and–most importantly–woven together by the connective thinking that’s quintessential to the liberal arts.

In enumerating the goals of a liberal education, William Cronon notes that “it is much easier to itemize the requirements of a curriculum than to describe the qualities of the human beings we would like that curriculum to produce” (1998, n.p.). In his tenth and final quality, he explains,

More than anything else, being an educated person means being able to see connections that allow one to make sense of the world and act within it in creative ways. Every one of the qualities I have described here—listening, reading, talking, writing, puzzle solving, truth seeking, seeing through other people’s eyes, leading, working in a community—is finally about connecting.

Small residential campuses immerse students in the experience of learning, so they’re constantly nudged (and at times forced) to juxtapose the classes and the disciplines they’re exploring. Like neural pathways, each of these connections becomes a new capacity for making sense of the world and acting creatively within it.

Students also come to understand not only what they are learning and how it’s all interrelated, but also why they are learning. The relevance of the multiple lenses afforded by a liberal arts education is frequently cited as the key to solving the societal and environmental problems that resist simple solutions. Students often experience the power of applying tools from very different subject areas when engaging with unfamiliar, challenging, and even controversial issues. On any campus, students can learn about global warming, or sexual violence, or responses to COVID-19, but at small liberal arts colleges, students can study them as complex issues that are even better understood by seeing them through biology, anthropology, and literature, or ecology, sociology, and art. Experiences like these help students discover motivations for learning that extend well beyond exams, papers, and projects.

Our campuses support these moments in a way that’s not possible without the foundations of trust that result from sustained, personal relationships with professors and peers. In their classes and in campus organizations, students have ample practice with the skills for grappling with complex and difficult topics. Through deep reading, reflection, and open but guided discussion in different contexts, students explore their own thinking, disagree with one another, stumble, negotiate, abandon or modify ideas that are no longer workable, and grow in a supportive environment where they routinely wrestle with ideas that are often avoided in common conversation. This sense of being “liberated” to fully consider difficult, complex issues is, in fact, the essence of the original sense of liberalis ars–or the art, skill, or practice of freedom.

Student-Campus

Whereas the primary locus of learning at larger universities is the individual classroom, learning happens everywhere at a small, residential liberal arts college. In a very real sense, the entire campus is a classroom, and everyone is an educator. The walls of its classrooms are porous, and students take with them what they’re reading, discussing, and mulling over when they walk across campus, eat breakfast, study in the library, practice on the field, read in the dining hall, and relax in their dormitories. These informal sites where students spend countless hours are combinations of study areas and what sociologists call “third places” (Oldenburg, 1989) like coffeeshops, bookstores, corner stores, or bars, where people from different contexts (not just friends or cliques) hang out, talk casually without an agenda, and build new communities.

Learning outside of the classroom also comes in more formal opportunities across campus. Students regularly contribute to decision-making processes by serving on governance and hiring committees, and leading honor councils. Some students on larger campuses get to participate in these ways as full campus citizens, but the number of options for each student to develop these professional skills at small liberal arts institutions is significantly greater. These regular interactions with librarians, deans, residence life staff, provosts, coaches, tutors, dining hall staff, counselors, program directors, IT support staff, and many others besides faculty form each student’s community on campus. They’re just as likely to talk about what they’re learning in chemistry class or in the history book they’re reading as they are about their family, a recent football game, the upcoming election, or their favorite movies. Their upcoming math exam is part of a conversation about the odds of a favorite team making it to the finals, and a description of a current research project leads to an introduction to an unfamiliar hobby. The theories that explain what motivates individuals and cultures overlap with advice about how to get along with roommates, and highly technical computer programs turn into a new challenge like the most popular computer games.

In these ways and more, everyone students interact with across campus becomes a potential mentor and partner in their learning. This “high-touch” experience of small liberal arts campuses means that it’s difficult for any student to fall through the cracks. In fact, one might say it’s harder not to engage with the many sites of learning on campuses like ours.

Student-Community

The history of private liberal arts colleges (see Brann, 1999) makes it easy to shorthand them as bucolic, isolated, exclusive, and elitist–a bubble designed to distance students from “real world” complexities and distractions. However, our institutions have dramatically changed how we relate to the world off campus. We do value the intimate community of faculty, staff, and students that our campus size supports; however, it is no longer the only community that figures largely in our students’ learning. In fact, our identities are often tied to the communities where our campuses reside, whether urban, rural, or suburban. Perhaps more vividly than any other aspect of our identity, the reach of campus relationships into our specific locations demonstrates the unique experiences for multidimensional engagement and personal growth offered at each campus. Our locations invite community service, career shadowing, internships, immersion in the natural world, engagement with local politics and social issues, and more. In these interactions, our students develop practices that carry over into each community within which they will intersect, reside, work, and learn from. Our prioritization of place—starting with but not limited to the local—scaffolds students’ experiences in understanding and finding their place within the broader, rapidly changing global community.

Increasingly, our campuses have developed partnerships with the industries, arts, nonprofits, and civic entities within our communities. Community-engagement programs blur the boundaries between on-campus classrooms and surrounding areas by leveraging learning in both environments. They blend student interest, faculty speciality, and community expertise to bring together theory and practice, to value the reciprocity between research and application. Further, the historic struggles for equity, access, and social justice that are explored in our classrooms are not siphoned off from their contemporary heirs, but instead are made more relevant by collaborating with members of the community who continue that work and welcome our students into that space. In the same vein, opportunities for guided vocational inquiry, professional practice, internships, and other career-oriented learning move fluidly from the classroom to our career planning offices to the workspace.

Our embeddedness within the larger community signals to our students that we are more than our curriculum and our residence life. Far from isolating students from societal concerns, professional norms, and practical skills, our surroundings enhance the distinction of being at our college. The learning opportunities our students find there not only extend the breadth of their education; these experiences help them practice what being an active part of a community requires of them. In this way, our campuses collapse the implied distance between town/gown, college/the real world, and school/work.

Student-Self

At the core of the mission of a small liberal arts college is the belief that the time on our campuses nurtures students’ development as whole persons who are inextricably connected to other whole persons and the world around them. They live and learn among peers with different belief systems, social locations, and dispositions. They confront complicated problems and join campaigns for justice. They navigate new information and integrate it with the old. All of the relationships described above become students’ different ways of knowing, so–in the same way that signature pedagogies prefigure a future in a particular profession–by learning on our campuses, students can’t help but wrestle with their “place” in the world.

By practicing these various ways of knowing in so many contexts–classrooms, offices, dining halls, and other shared spaces–students are learning how to hold multiple and ever-shifting identities. The goal isn’t to lose their sense of who they are but instead to learn who they are even more deeply, and, in doing so, explore who they want to become. Ongoing reflection fosters self discovery, self liberation, and self sustainability, while the connectedness forged in the sites of learning described above situate this self-awareness within the world around them. They thus cultivate habits of “becoming” that make students authors of their own experiences and empathetic readers of others’. And somewhat paradoxically, given our framework of deeply relational and embedded learning, we recognize that our students’ “becoming” is ultimately their accomplishment, and hope that they come away from our campuses with the knowledge that their education was distinctly theirs.

Like a liberal arts curriculum in which the sum knowledge of different disciplinary perspectives is its strength and uniqueness, learning on campuses like ours is ultimately the totality of the different contexts for learning, developed not in a single course but across students’ entire educational experience.

All of these experiences are intentionally supported by integrative activities that foster meaningful connections between the entirety of what they’re learning and their futures beyond campus. From their orientations even before the first day of class, they’re charged with forming their own interconnections throughout their experience. They participate in end-of-year summits in which they publicly present what they’re learning. They take multiple capstone experiences that provide guided but independent opportunities to synthesize various programs of study. Through formal classroom experiences and through informal events and conversations, they’re frequently asked about how they connect their various courses to their chosen majors; or how their experiences in the arts, sciences, humanities, and social sciences provide tools for understanding the world’s most pressing problems; or how their learning thus far is preparing them to be 21st-century citizens. And, perhaps most importantly, many of their assignments across the curriculum are reflective or metacognitive, prompting them to be aware of how their thinking is evolving, and how this development contributes to their sense of self, their understanding of others, and their chosen paths for the future.

Conclusion, or Liberal Learning in the Time of Remote Instruction

We acknowledge that the individual components of this framework are generally available on a range of campus types and unique to none. However, it is the intentional presence and integration of all seven on a single campus that distinguishes small, residential liberal arts campuses. We offer integrated, developmental, campus-wide efforts to educate students by transcending curriculum, classroom walls, single semesters, and even our physical campuses. Our students learn through the ongoing interaction of these different connections, which ultimately helps them become who and how they are going to be in the world. Learning happens here within an ecosystem that fosters, enables, and empowers student learning and growth. This is the signature pedagogy of the small, residential liberal arts campus.

Following Shulman’s challenge to identify pedagogies that align with specific ways of thinking, knowing, and doing, many academic disciplines have noted how some of their traditional practices have fallen short. Some identified default activities that are either so generic that students experience none of the disciplinary intentions (e.g., the history survey as a string of facts, rather than the “cognitive habits” of historical thinking [Calder, 2006, p. 1364]) or even so contradictory to the goals that the origins of students’ common misconceptions become clear (e.g., literature professors presenting their fully formed interpretations and expecting students to then develop their own [Chick, 2008]). And so, as with other signature pedagogies, what we’ve offered here is partly descriptive and partly aspirational. Not all of our students experience their learning in this way, and our campus practices don’t always align with our intentions.

Certainly, the emergency shift to remote learning in the spring of 2020 fell short of our ideals. However, that pivot was necessary, urgent, and unplanned, and it’s been widely misunderstood (Bessette, Chick & Friberg, 2020). What matters to us now is what’s ahead. We’re all uncertain about the fall, including where our students will be and where classes will be held. This is precisely why we must fully articulate how learning happens in our institutions. Guided by our framework, we can then see beyond our physical classrooms and be intentional in reaching toward our ideals in virtual environments.

Recommended citation:

Chick, Nancy, Kent Anderson, Stephanie Rolph, Betsy Sandlin, and Linda Boland. 2020. “Distinctive Learning Experiences: Can we identify the signature pedagogies of residential liberal arts institutions?” Accessed [date, year]. http://blogs.rollins.edu/endeavor/2020/05/12/distinctive-learning-experiences-can-we-identify-the-signature-pedagogies-of-residential-liberal-arts-institutions/

Read the next post, “Planning Our Distinctive Learning Experiences” for a planning tool that may help with next steps.

One thought on “Distinctive Learning Experiences:

Can we identify the signature pedagogies of residential liberal arts institutions?”