Step 1: Defining Effective Teaching

Before doing any evaluation, pause and consider what you mean by “effective teaching,” the standard by which you’ll be evaluating your peers.

Explore the selected frameworks to the right for examples and inspiration:

- ”Critical Teaching Behaviors” (Barbeau & Happel) — an instrument for comprehensive evaluation based on “six categories of evidence-based instructor behaviors proven effective in increasing student learning gains and retention”; includes how and where these behaviors can be documented (See their 2023 book Critical Teaching Behaviors: Defining, Documenting, and Discussing Good Teaching for details.)

- USC’s Definition of Excellence in Teaching (USC) — The University of Southern California’s definition was also used to make a detailed rubric (linked in “Ready-to-Use Instruments for Peer Observation” below).

- Teaching Quality (TEval.net) — The TEval.net Project’s 7 dimensions of quality teaching are listed at the top of this rubric, and are mapped in slightly different ways by the participating institutions. See TEval’s various resources here.

- The “Developmental Framework for Teaching Expertise” (Kenny, et al) — a detailed framework that maps the growth of teaching expertise across all career stages (the tool starts on p5; see brief intro/explanation [Chick, et al])

Step 2: Understanding Your Lens

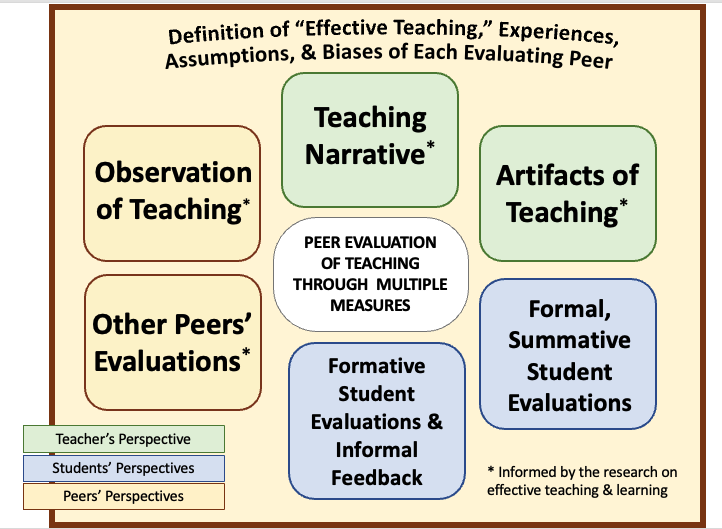

As outlined on the “How to Document Effective Teaching” site, Stephen Brookfield presents a framework of four lenses for more fully examining teaching: 1) one’s own, 2) one’s students’, 3) one’s peers’, and 4) the literature on teaching and learning in higher education, which is engaged by the other perspectives.

This framework can also be used to ensure systematic documentation and evaluation of teaching, by using multiple kinds of evidence from multiple points of view, especially in summative evaluations — which can help mitigate some of the limitations and biases in evaluating teaching.

This site focuses on the “peer” lens by offering multiple ways to evaluate a colleague’s teaching: a) class observation, b) teaching narratives, c) teaching artifacts, d) external letters, and of course e) students’ perspectives.

As you evaluate a colleague’s teaching directly (via classroom observation) and indirectly (by seeing through others’ perspectives), keep in mind that all of your evaluations are still filtered through your perspective — your experiences, your assumptions, and your biases.

Monitoring the influence of these experiences, assumptions, and biases is thus necessary to a fair evaluation of teaching.

Monitor Your Lens

See these two short pieces on recognizing, monitoring, and reducing your biases during evaluations. (Coming soon: new & improved resources on bias!)

Step 3: Using Tools to Guide Your Evaluation

One way to monitor the influence of your experiences, assumptions, and biases in evaluating a peer’s teaching is to use tools that focus and guide your observation according to your definition of effective teaching.

Classroom Observation

The Classroom Observation Process

Peer observations of teaching for review, tenure, and promotion processes typically follow a standard set of good practices divided into three stages: before the observation, during the observation, and after the observation. A key part of that process is considering and mitigating the observer’s potential biases.

Classroom Observation Instruments

During the observation, the observer can either use an existing, ready-to-use instrument, or customize an observation protocol to match specific aspects of “effective teaching” and types of classes. Resources for both options are below.

Option 1: Use Ready-to-Use Instruments

Below is a selection of existing instruments, ranging from simple to complex, but all effective:

- A simple observation tool focusing on instructor’s goals, alignment of activities, student engagement, & instructor awareness of student learning

- A rubric based on USC’s detailed definition of excellence in teaching

- A detailed rubric and documentation tools based on Barbeau & Happel’s 6 categories of “Critical Teaching Behaviors,” “evidence-based instructor behaviors proven effective in increasing student learning gains and retention”; includes how and where these behaviors can be documented

- An instrument based on Chickering & Gamson’s “7 Principles of Good Practice in Undergraduate Education” with indicators for evidence for each principle and where it can be observed in F2F or hybrid/virtual courses

- COPUS (“Classroom Observation Protocol for Undergraduate STEM”): systematic log of specific activities, designed for STEM but adaptable across disciplines; includes training guide (also see LOPUS for Lab Observations, in “lab/fieldwork” class type to the right)

- RTOP (“Reformed Teaching Observation Protocol”): tool developed for reformed K-20 science and math courses, but the tool itself is useful across disciplines; includes training guide

- Physics Observation Protocol: very detailed form developed for Physics but parts could be adapted across disciplines

Option 2: Customize a Class Observation Protocol

Fair and effective peer observations are guided by decisions about what aspects of teaching will be evaluated, what behaviors will demonstrate those elements, and how to document the observation. Rather than using an existing instrument, you can make your own following the 2 steps below:

1. WHAT do you want to evaluate through classroom observation? Explore these collections of observable teaching behaviors for different aspects of teaching, compiled from existing instruments:

Aspect of Teaching

* engagement & interaction

* classroom environment

* organization & structure

* support for student learning

* equity & inclusion

Context/Type of Class

* virtual class

* course website

* lab/fieldwork

* lecture

* clinical session

2. HOW will you focus and document your observation as it happens? Below are two ways to provide structure and help prevent bias during your observation by guiding how you record examples of learning or engagement, and how you note analysis and recommendations (Gleason & Sanger):

- Documentary: chronological log of class activities [samples/templates]

- Thematic: pre-identified areas to focus on [samples/templates]

Assessment of Teaching Narratives

The teaching narrative or statement is not an intuitive piece of writing. It’s typically written directly in response to the institution’s instructions and expectations. Before you evaluate this document, review this explicit guidance that has been communicated to the candidate. This guidance for the candidate should also be the guidance — the tools — for your evaluation.

Often, candidates are expected to “reflect on their teaching” within this narrative. This typically means the following:

| Component of Reflection | How to Assess |

| Self-awareness of their own strengths and weaknesses | How does their self-assessment of their strengths and weaknesses align with the other evidence provided? With your definition of effective teaching? |

| Responsiveness to feedback from students and peers | In their discussions of student evaluations, classroom observations, and previous review letters, does the narrative address specific concerns and recommendations with comprehension, and with EITHER acknowledgement and a plan for improvement OR an effective counter-perspective? |

| Demonstration of growth over time | How does the narrative illustrate the candidate has learned something about their teaching? See sample tools for assessing growth or development here. |

Evaluation of Teaching Artifacts

Request artifacts that will provide evidence of specific aspects of your definition of effective teaching (Step 1 above). Especially when annotated, these artifacts can document key issues like course design, illustrations of student learning expectations, compliance with department/institution guidelines, constructive alignment (learning outcomes-assessments-activities), disciplinarity, varied assessments, approach to student feedback, patterns in student performance, rigor, attention to diversity-equity-inclusion, and more.

Some examples of these materials, along with sample tools for evaluation, are below. As you review any artifacts, ask What does this particular material provide evidence of? (And what does it not provide evidence of?)

Artifacts of Teaching Performance

* syllabi from previous, new, or redesigned courses (sample evaluation tools)

* assignments and accompanying rubrics (sample evaluation tool)

* instructor’s feedback to students on anonymized samples of student work

* evidence of reasonable time to return graded work

* plans for a class session, lecture notes

* instructor’s curated highlights of student evaluations for a particular course, a course type, or a single question on the evaluations across time–with brief annotation about strengths, growth, and/or continued challenges

Artifacts of Student Performance

* anonymized samples of above average, average, & below average student work, possibly with grade distribution of assignment (sample evaluation tool)

* anonymized samples of work from the same student(s) to show evidence of growth (sample evaluation tool)

* grade distribution of all courses taught, or specific course types

What else? Think about what traits you’re looking for, and where you’d find them.

–> The “Critical Teaching Behaviors” (Barbeau & Happel) instrument has a column indicating where different teaching traits and behaviors are documented.

If you’re looking for tools to focus on evidence of the instructor’s attention to diversity, equity, and inclusion (DEI) across materials, see this collection of DEI evaluation tools. (They’re also included in the relevant samples throughout this document.)

Reviewing External Peer Evaluation Letters

Some institutions invite relevant experts from outside the institution to provide letters of evaluation.

In An Inclusive Academy, Abigail Stewart and Virginia Valian recommend “a high degree of skepticism about the weight [these letters] should have in the evaluation process” (p. 356) and provide guidance on how to request and evaluate them effectively (pp. 355-360; [direct link to pages in Olin Library’s electronic copy]).

Considering More Examples of Students’ Perspectives

In addition to formal end-of-semester student evaluations of teaching administered by the institution, you may consider multiple ways of capturing different moments of students’ experiences and perspectives. For instance, what would each of the following tell you? And while some by themselves are certainly insufficient, what do they contribute to a more holistic picture of teaching effectiveness?

- responses to anonymous mid-semester or end-of-semester surveys tailored to the course (if truly anonymous, can be administered by the colleague or by a third party)

- notes from current students (solicited or unsolicited)

- letters from former students about longer-term impact, solicited and collected by a third party

- teaching awards adjudicated by students

A Caution

There is plenty of evidence challenging the practice of relying too heavily on students’ assessments of teaching quality (e.g., the “Statement on Student Evaluations of Teaching” from the American Sociological Association, Rollins’s white paper on student evaluations, or this review from Auburn University’s Teaching Effectiveness Committee).

While these statements focus on formal student evaluations, the biases that affect students’ perspectives influence informal assessments as well. This is one of the reasons why using multiple measures to evaluate teaching is essential.

This site is licensed under a CC-BY-NC (Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial) 4.0 International License.

Nancy Chick, Endeavor Foundation Center for Faculty Development at Rollins College, 2021