by Dr. Yunxiang Gao

Soo Yong

This month we are pleased to have a guest contribution from Dr. Yunxiang Gao, Professor of History at Ryerson University in Toronto, whose forthcoming biography retrieves the life and career of Soo Yong, a Chinese American actress and cultural ambassador in the twentieth century. Soo Yong was a resident of Winter Park and close friend of Rollins College for two decades. She also established the C. K. and Soo Yong Huang Memorial Fund to support the learning of Chinese culture at Rollins. For her contributions to our academic community, Soo Yong was awarded the Rollins Decoration of Honor in 1961, the first individual of Asian heritage to receive such recognition from the College.

Dr. Gao has authored two books: Arise, Africa! Roar, China!: Sino-African-American Citizens of the World in the Twentieth Century (Chapel Hill, NC: University of North Carolina Press, 2021) and Sporting Gender: Women Athletes and Celebrity-Making during China’s National Crisis, 1931-45 (Vancouver: UBC Press, 2013).

*******

Soo Yong (杨秀 ca. 1903-1984), stage, film, and television actor, monologist, and cultural interpreter, was a resident of Winter Park and close friend of Rollins College for decades. During her vibrant career that spanned from the 1920s until the early 1980s, Soo Yong played small but significant parts in major Hollywood productions. She also appeared in many dramatic presentations at Rollins College.

Born in Hawaii to first generation Chinese Americans, Soo Yong (originally Young Hee 杨喜), was orphaned as a child, and largely raised by her sister, Harriet, who was later a force in Hawaii politics. After graduation from the University of Hawaii, Soo Yong arrived in mainland United States in 1926 to earn an M.A. at Teachers College, Columbia University in New York. She then began a career with bit parts in Broadway productions, joined by her new husband, Peter Goo Chong. The couple divorced in 1933.

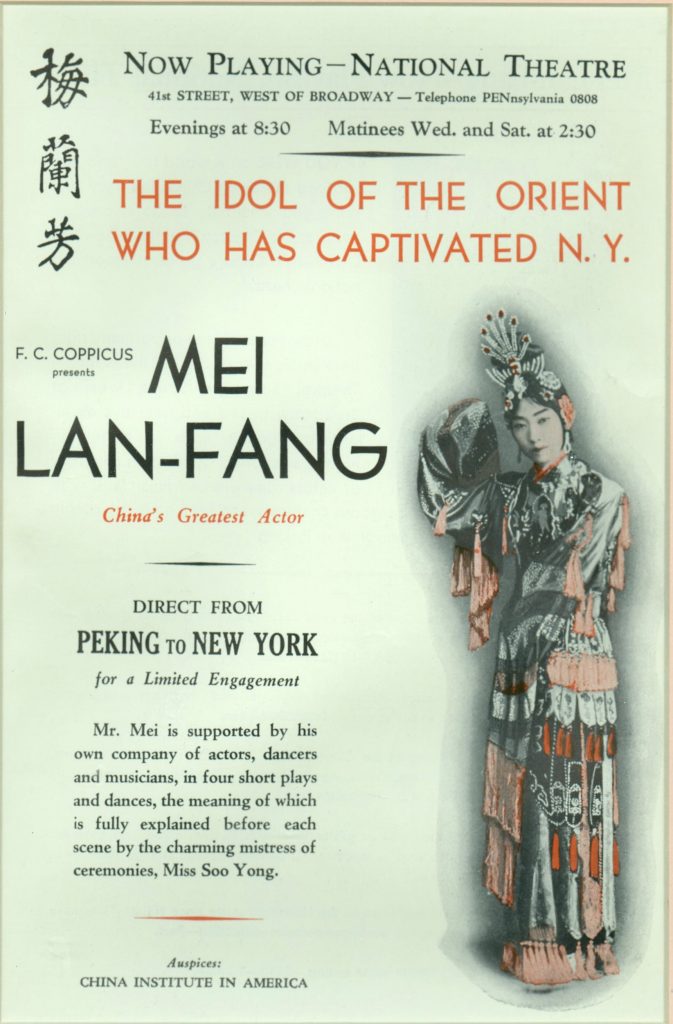

Soo Yong’s big break came in 1930 when she was hired to interpret the Broadway performances of Mei Lanfang, the famous Chinese theatrical personality. Before and during each of Mei’s fully-attended performances, Soo Yong explained plot lines and thespian nuances to the audiences, few of whom understood Mandarin. She also interpreted for Mei during interviews. After many months in Broadway, the company toured the United States before completing its running in Los Angeles where Yong encountered numerous Hollywood producers, directors and actors and key members of local Chinese American society and Chinese diplomatic corps. She enrolled in a doctoral program at the University of Southern California.

Soo Yong’s name is prominently mentioned in the poster advertising Mei Lanfang’s performance in New York, 1930. (Image: Courtesy of Dr. Yunxiang Gao)

White Hollywood was smitten by Soo Yong, whose educated, middle-class persona contrasted with the flamboyant and controversial star Anna May Wong. Wong’s film persona, created for her by racist Hollywood casting decisions, irritated China’s Nationalist government. Soo Yong’s profile matched well with the Chinese New Woman concept that emphasized education, chastity, patriotism and employment in nursing, teaching or homemaking. The highly influential 1943 visit to the United States by Madam Chiang Kai-shek dominated the contentious process of representing China, particularly Chinese womanhood, across the Pacific. Soo Yong had uniquely embodied Madam Chiang’s type of glamour, which was defined by jewelry, high fashion, and beauty, as well as perfect English, advanced education, sophistication, respectability, and a happy marriage. The Chinese Digest, the leading English-language Chinese publication in the United States, observed as early as 1939 that Soo Yong belonged to “Madame Chiang’s school” of women.

Hollywood filmmakers had already given Soo Yong steady work. Entranced by Soo Yong’s talents and assuaged by favorable Chinese attitudes toward her (China was a significant market), Hollywood casting agents chose Soo Yong for visible roles in 1930s hit films starring such superstars as Greta Garbo, Mae West, Cary Grant, and Clark Gable. After Anna May Wong rejected a lesser role in the 1937 film adaptation of Pearl Buck’s Nobel Prize-winning novel, The Good Earth, Soo Yong accepted two parts in the movie. However antiquated the film appears today, it was a huge hit, winning numerous Oscars, and became a sizable credit in Soo Yong’s resume. She continued in secondary but important roles, which evolved from maid, sophisticated businesswoman, to tough political leader into the 1950s. Unlike Wong, who often had to display bare skin and perform sexualized roles, Yong was always fully clothed and displayed dignity and sophisticated glamour in her parts. Unlike Wong’s, Yong’s roles never involved physical abuse or death.

When not in front of the camera, Soo Yong assembled monologues taken from classical Chinese drama and poetry. Starting with performances in elite southern California Chinese homes, she offered her “one woman’s show” across the nation, often in support of United China Relief, a philanthropy that combined patriotism with financial help for war-ravaged Chinese.

Soo Yong and Clark Gable, in an inscribed still from the film China Seas (1935) published in The Young Companion Pictorial, allegedly the most popular magazine in Republican China. (Image: Public Domain)

In 1941, Soo Yong married C.K. Huang (黄春谷), a businessman who lived in Winter Park, Florida when not pursuing deals in South America and Europe, after changes in immigration law enabled her to marry a Chinese citizen without losing her citizenship. Huang was a classmate at Nankai University in Tianjin of Zhou Enlai, later the famed Prime Minister of the People’s Republic of China. Outside of Yong’s career travel, the couple divided their time between Winter Park and a home in Boothbay Harbor, Maine. While continuing to take up roles in Hollywood and crisscross the country to perform monologues, her part-time job was to help run the family’s successful Chinese novelty shop on Park Avenue in Winter Park. Named the Jade Lantern, the shop afforded them a comfortable life. The shop modeled a luxurious Asian domesticity along with arts and crafts, jewelry, handbags, embroidered silk, linen, and furniture. Soo Yong advertised such high-end Chinese material culture through her celebrity. Customers shopped there for a life style associated with her glamor and were served by the star they recognized from stage and screen.

Soo Yong serves a customer in her family shop Jade Lantern in Winter Park, Florida. (Image: State Archives of Florida)

The Huangs became active supporters of Rollins College. In the 1940s, she performed monologues derived from her distinguished career in Hollywood films and from her national speaking tours for the Rollins Animated Magazine, an innovative forum in which authors appeared in Winter Park once a year to read their articles. Soo Yong appeared on stage with such luminaries as Edgar A. Morrow, Mary McLeod Bethune, actress Greer Garson, scholar Liu Wuji, and the former Chinese Ambassador to the United States Wellington Koo and his wife, who stayed at the Huangs’ home during their visit. Soo Yong directed and staged Lady Precious Stream, the widely acclaimed Broadway play adapted by Chinese playwright Hsiung Shih-I from the classical Peking opera program, with Rollins College students. When the program premiered at the Annie Russell Theatre on campus from March 26 to 30, 1946, she first appeared on stage as the “honorable reader,” using the model she first employed in Mei Lanfang’s presentation. Her Rollins College productions were a family endeavor; Huang made the hats for the costumes designed by his wife for the cast and performed as one of the two “property men” characters. The Huangs were also very active in the local Congregational Church.

Soo Yong with Hamilton Holt, long-term president of Rollins College, and other speakers, including the noted scholar Liu Wuji, for the 1948 issue of the Animated Magazine.

Soo Yong continued to secure roles in Hollywood productions in the 1950s and early 1960s. After years of patient service in mediocre films, she was rewarded with supporting roles in some of the decade’s most important Orientalist productions. In 1955, she played in the film adaptation of the Han Suyin novel, Love Is a Many-Splendored Thing. She played a dancing troupe manager in the 1957 Paramount Pictures World War II epic, Sayonara, in which Marlon Brando starred as a racist air force pilot who falls in love with a Japanese woman. Soo Yong capped her cinematic career, which boasted roles in twenty-three Hollywood films, with a strong performance as the stern aunt of playboy Jack Soo in the 1961 Rodgers and Hammerstein hit film, Flower Drum Song.

During these years, the Huangs traveled extensively in South America and visited China in 1948. There, they recorded two rare Cantonese operas and released them on two albums on Folkways Records in 1960 and 1962. The Huangs lived in Winter Park until 1961, when they returned to Hawaii. That year, they were awarded the Rollins Decoration of Honor. Soo Yong’s acting career now slowed to a trickle. She secured small parts in Hawaiian-themed television shows, including four episodes of Hawaii Five-O between 1971 and 1978, in which her husband also appeared, and spots in two episodes as the “Old Woman,” in Magnum P.I. in 1981 when she was seventy-eight years old. C. K. Huang died in 1980; Soo Yong passed away in 1984. The couple’s estate established scholarship funds at the University of Hawaii and at Rollins College.

The Huangs are honored at Rollins College, 1961.

Soo Yong’s legacy shines brightly as a positive pioneer for Chinese Americans. At a time when Chineseness was associated with ignorance and servitude, the beautiful, educated, American-born Soo Yong repudiated such notions and showed a cosmopolitan “Chinese woman at her best.”