by Sierra Short ’22

President Edward P. Hooker (front row, seated on the right) with Rollins faculty members at Pinehurst Cottage, 1891 (Photo: Rollins College Archives)

In celebration of Women’s History Month, we are pleased to present the first in a series of blog posts written by students in Prof. Claire Strom’s Fall 2020 class, Researching American History. The Archives staff is grateful to Prof. Strom and her students for sharing their work with us.

*****

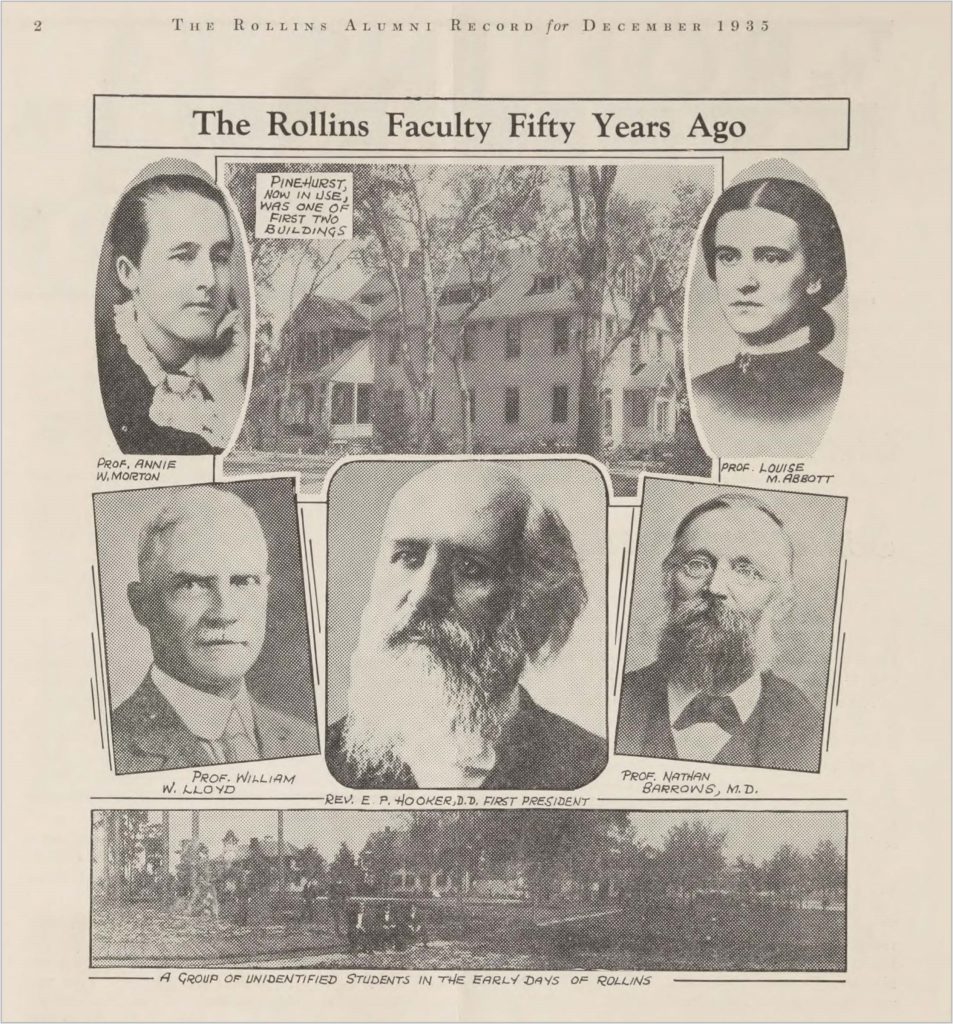

On opening day on November 4, 1885, the first students of Rollins College were greeted by five charter faculty members: President Edward P. Hooker, Dr. Nathan Barrows, Annie Morton, William W. Lloyd, and Louise Abbott.[1] It was the intention of the founders, and of President Hooker, to hire “the best faculty that can be found.”[2] However, this faculty of Rollins – both the Charter Faculty and the other twenty-two professors hired during President Hooker’s seven-year administration – was distinct from that of other schools in the late nineteenth century in that it was majority female.[3] Of the twenty-six professors, only twelve were male, while fifteen were female. This was accidental, caused by Rollins’ status as a new, coeducational institution in Central Florida; at the time, this area of the country was difficult to access, and a not-yet-established school in that environment would not be the first choice for the top academics, who tended to be men.

The College’s charter faculty members, as pictured in the Rollins Alumni Record, December 1935 (Image: Rollins College Archives)

As a coeducational institution, Rollins provided an opportunity for female professors that they could not get at most other schools. Rollins College’s establishment as a coeducational college in 1885 was unique; in the late nineteenth century, most colleges – particularly those in the North – were still single-sex institutions, and even at northern coeducational schools, women professors were not common. Oberlin College – founded as a coeducational institution in 1833 – had far more male faculty than female faculty; its catalogue from 1890 to 1894 shows forty-eight men versus twenty-one women.[4] At that time, even women’s colleges tended to have more male professors than female; Bryn Mawr, another school established in 1885 as a women’s college in Pennsylvania, only had four female professors compared with their nine male professors in the 1885-86 academic year.[5] On the other hand, Stetson University, Rollins’s closest neighbor and another coeducational school founded as a college in the same year, showed the same trend as Rollins: in their 1888-89 catalogue, Stetson had three male professors and six female professors.[6] [Note: The 1887 catalog of DeLand University, as Stetson University was then known, states that the first collegiate freshman class would be established in October 1887.] While established in the same year as Bryn Mawr, Rollins and Stetson were located in what, at the time, was a rural part of Central Florida. Therefore, Rollins ended up with a less qualified faculty than the northern schools, with a smaller selection of willing contenders for faculty positions.

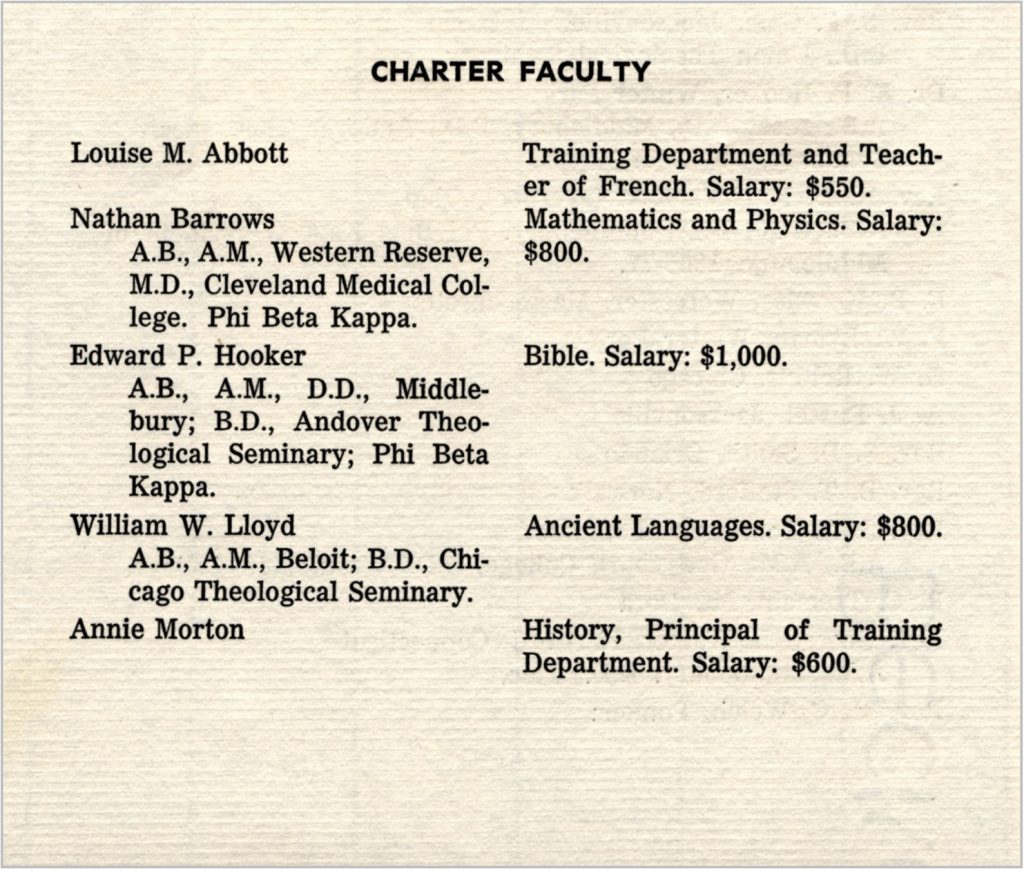

The charter faculty, as listed in The First Seven Years of Rollins College (Image: Rollins College Archives)

The Rollins professors tended to be less educated and less experienced in academia than those at other schools. While almost every member of Bryn Mawr’s faculty had a doctoral degree, and most at Oberlin had at least a master’s degree, Rollins’ faculty was made up mainly of professors with bachelor’s degrees.[7] President Hooker, along with the two other men of the charter faculty, Barrows and Lloyd, all had doctoral degrees; however, the two women of the charter faculty only had bachelor’s degrees.[8] It was not that women did not try to become as educated as their male colleagues, but that there was no opportunity to do so; Bryn Mawr, founded in 1885 – the same year as Rollins – was the first school that offered a PhD program for women, and before then it was hard for women to even be admitted into master’s programs.[9] Due to their credentials, both Abbott and Morton were hired to teach in the Training and Preparatory Departments. When Rollins was founded, it had four departments: the Collegiate Department, the Preparatory Department, the Training Department, and the Industrial Training Department.[10] The Collegiate Department taught classical studies, modern languages and sciences; the Preparatory Department (for which many female professors were hired) taught high-school aged students; the Training Department (that Abbott and Morton worked in) prepared students to become teachers; and the Industrial Training Department functioned as a trade school.[11] Abbott and Morton taught in the Training Department, as well as teaching French and history, respectively, in the Collegiate Department.[12] Eva J. Root, a professor hired in 1890, was well qualified for academia, with a master of arts degree and experience teaching natural science, French, and English.[13] At Rollins, she “was [first] assigned to the principalship of the preparatory school,” the same position that Abbott had before her, and this was a “disappointment to [Root],” so much so that “had it not been that for reasons of health she was obliged to live in the South, she might have refused to remain.”[14] The Preparatory Department, with more of the female professors, was considered less prestigious to work in, since it was not at the university level. Although these women taught in these less prestigious departments, all three of them eventually taught in the Collegiate Department as well, and both Abbott and Root held the position of chair to the preparatory school. Root’s reason for staying – that Florida had better weather for her health – was common among many of the professors that taught at Rollins in this period.

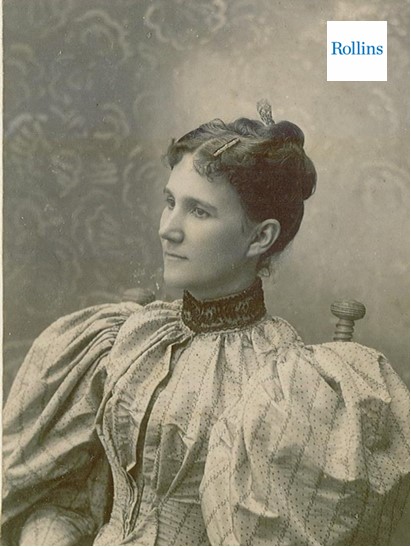

Portrait of Prof. Eva J. Root (Photo: Rollins College Archives)

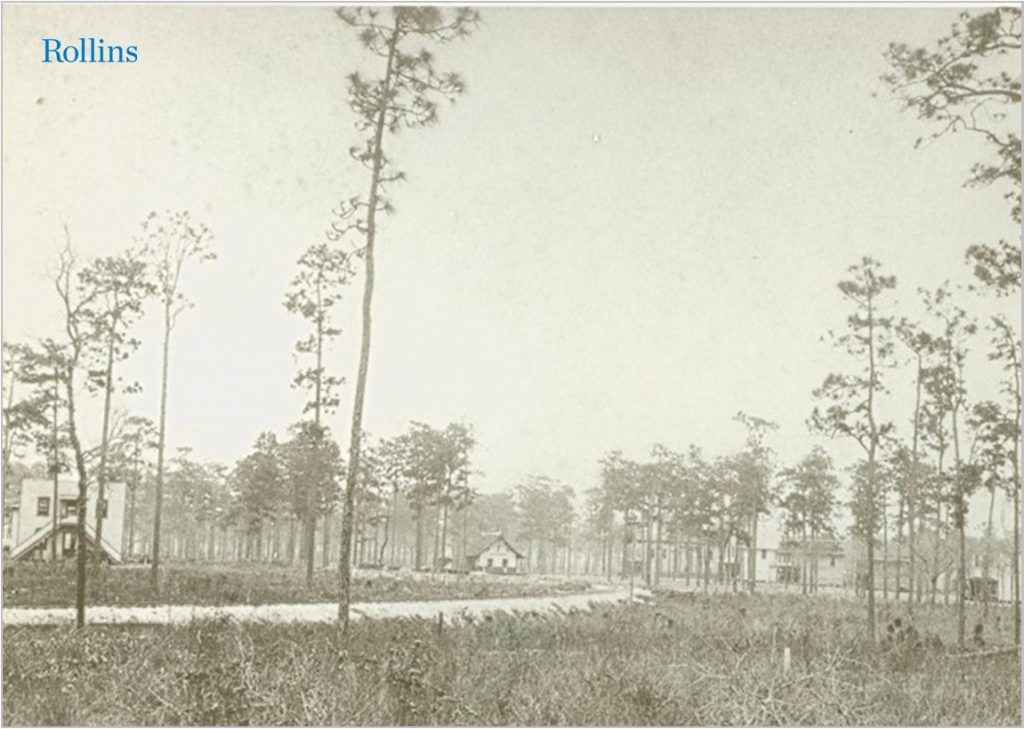

Location was paramount at a time when travel was hard, and most professors based out of New England would not have been willing to make the arduous journey to a not-yet-established school in Central Florida. In an early photograph of downtown Winter Park, all that can be seen is a few buildings among the sandy, long-leaf pine habitat of Central Florida. One of the Rollins’s charter faculty members, William W. Lloyd, wrote of his experience traveling to Rollins and Winter Park for the first time in 1885. He traveled to Florida from Chicago and then, from Jacksonville, he came “up the St. Johns River on the steamboat by night, the search light thrown from side to side on the black, pitchy waters hemmed in by forests of water oaks and pines,” until he arrived in Sanford.[15] There, he boarded a train, and when he arrived “in Winter Park, he seemed to be set down in a forest of telegraph poles in a sandy desert.”[16] Just as the photograph captured, there were very few buildings in what was otherwise an uninhabited terrain. Winter Park was not yet established as a town at this point; it was chartered in 1887, two years after Rollins was founded, and was mostly made up of northerners fleeing the cold weather – the same group of people that Rollins attracted.[17] It is unclear how many people lived in Winter Park at the time of its founding, since many of those that did were seasonal – only living in Winter Park during the colder months.[18] Similar to Rollins, both Oberlin and Bryn Mawr were based in small towns that were founded around the colleges.[19] Even so, they differed in that transportation between these towns and surrounding cities was faster than the multi-day trip from the North to Winter Park; the city of Bryn Mawr was a suburb of Philadelphia, and Oberlin was located only 35 miles from Cleveland.[20]

Downtown Winter Park, circa 1884 (Photo: Rollins College Archives)

Dr. Jack C. Lane, a prominent Rollins College historian, argues that “despite its frontier location, the obscure little college was able to attract a distinguished faculty because many educated northerners had begun the tradition of vacationing in the state.”[21] The early faculty of Rollins was made up of professors that chose to come to Rollins, in some cases having been offered other positions at more prominent schools, because they thought that the warm climate of Florida would be more pleasant than the cold North. Abbott, Lloyd, and Morton were “in retirement in Florida when Hooker hired them,” each hoping that time in the warm Florida climate would be healthy for them and help them overcome illnesses.[22] However, they were likely not President Hooker’s first choices for his faculty; before opening day, Hooker travelled north “to raise funds, to seek students and to hire ‘the best faculty that can be found.’”[23] While successful in finding donors up north, according to Lane, Hooker and his executive committee “found a sufficient number of qualified faculty living in Florida.”[24] Even so, it is likely that Hooker’s original trip up north was not successful in finding academics willing to relocate. Hooker did meet Abbott in New England, however; they met “at the home of Governor Stewart of Middlebury,” in Vermont, at which point Hooker invited her to be the head of the Rollins Preparatory Department.[25] The “most outstanding charter faculty member,” Barrows, came to Florida in 1882, moving from Ohio to “Orange City, where he made a beginning in fruit raising,” due to his interest in botany.[26] While these professors were willing to come, their reasons for doing so were related to their personal health and lifestyles, and it is likely that many other northerners would not have felt the same inclination to travel south, preferring to stay at better known northern institutions in more populated areas.

Rollins College would have been convenient for those professors already intending to live in Florida, and unattractive to those who were not. At its founding, Rollins College would not have been attractive to most academics, as it was far away from other, more prominent schools, and located in an unpopulated area. New England schools were in well-established areas, nearer to cities and to one another. Public transport there was much more accessible than what Professor Lloyd experienced on his trip to Winter Park. It was for this reason that Rollins hired so many female professors, because it could only convince a select group of people to come to teach at Rollins in its formative years. The women Rollins hired were more likely to end up teaching in the Preparatory Department or the Training Department than the more prestigious and competitive Collegiate Department. Still, due to its inability to hire more prestigious and qualified professors like well-established, northern schools could, Rollins presented opportunities for women to take positions that would otherwise be given to men.

Prof. William Webster Lloyd (fourth from the right), the only surviving member of the charter faculty, returned to campus in 1935 for the College’s Semi-Centennial celebration. He is shown here at the dedication of a memorial to the charter faculty, accompanied by some of the College’s charter students, including the first Rollins graduate, Clara Louise Guild ’90 (third from the left). (Photo: Rollins College Archives)

*****

[1] Jack C. Lane, Rollins College Centennial History: A Story of Perseverance 1885-1985 (Winter Park: Story Farm Inc., 2017), 26; “History of 50 Years at Rollins Story of Achievement,” Orlando Sunday Sentinel-Star, Orlando, Florida, October 27, 1935.

[2] Lane, Rollins College Centennial History, 23.

[3] “The First Seven Years of Rollins College,” Rollins College Bulletin 1955, Rollins College Scholarship Online, Rollins College, Winter Park, Florida.

[4] “Oberlin History,” About Oberlin, Oberlin College and Conservatory, accessed December 8, 2020; “Course Catalog 1890/91-1893/94,” Course Catalog, Oberlin College, Oberlin, Ohio, https://babel.hathitrust.org/cgi/pt?id=uiug.30112112239212&view=1up&seq=14.

[5] “History,” About Bryn Mawr College, Bryn Mawr College, accessed December 8, 2020, https://www.brynmawr.edu/about/history; “Bryn Mawr College Program, 1883-1894,” Special Collections, Bryn Mawr College Library, Bryn Mawr College, Bryn Mawr, Pennsylvania, https://archive.org/details/brynmawrprogram1894bryn/page/n29/mode/2up.

[6] “History of Stetson University,” About Stetson University, Stetson University, accessed December 7, 2020, https://www.stetson.edu/other/about/history.php; “Fourth Annual Catalogue of the Officers and Students of John B. Stetson University,” Bulletin 1889, University Bulletins-Catalogs Collection, Stetson University, duPont-Ball Library, https://digital.archives.stetson.edu/digital/collection/StetsonCatCol/id/2731/rec/5.

[7] “Bryn Mawr College Program,” Special Collections, Bryn Mawr College Library; Course Catalog, Oberlin College; “The First Seven Years of Rollins College,” Rollins College Bulletin 1955.

[8] “The First Seven Years of Rollins College,” Rollins College Bulletin 1955.

[9] Barbara Miller Solomon, In the Company of Educated Women: A History of Higher Education in America (New Haven: Yale University Press, 1985), 134.

[10] Lane, Rollins College Centennial History, 37; Catalog Card for Annie Morton, File 45 E, Archives and Special Collections, Olin Library, Rollins College, Winter Park, Florida.

[11] Lane, Rollins College Centennial History, 37.

[12] “The First Seven Years of Rollins College,” Rollins College Bulletin 1955.

[13] “An Appreciation of Miss Eva Root,” The Rollins Alumni Record (June, September, and December 1931), Rollins Archives, Olin Library, Rollins College, https://lib.rollins.edu/olin/oldsite/archives/golden/Root.htm.

[14] “An Appreciation of Miss Eva Root,” The Rollins Alumni Record.

[15] Lane, Rollins College Centennial History, 26; D. Moore, “A Young Professor at Rollins, 1885-86,” Archives and Special Collections, Rollins College.

[16] Lane, Rollins College Centennial History, 26; Moore, “A Young Professor at Rollins, 1885-86.”

[17] City of Winter Park, “History,” About, accessed December 15, 2020. https://cityofwinterpark.org/government/about/history/.

[18] City of Winter Park, “History.”

[19] City of Oberlin, “History of Oberlin,” For Visitors, accessed December 17, 2020, https://www.cityofoberlin.com/for-visitors/history-of-oberlin/; Bryn Mawr College, “Town and City,” Outside the Classroom, Accessed December 17, 2020, https://www.brynmawr.edu/postbac/outside-classroom/town-and-city.

[20] Bryn Mawr College, “Town and City,” Outside the Classroom; Oberlin College and Conservatory, “In and Around Oberlin,” Life at Oberlin, https://www.oberlin.edu/life-at-oberlin/in-and-around-oberlin.

[21] Jack C. Lane, Rollins College: A Pictorial History (Tallahassee: Rose Printing Company, 1980), 6.

[22] Lane, Rollins College Centennial History, 52.

[23] Lane, Rollins College Centennial History, 23.

[24] Lane, Rollins College Centennial History, 26.

[25] “Louise Maria Abbott (1836-1917), Archives and Special Collections, Olin Library, Rollins College, Winter Park, Florida.

[26] Lane, Rollins College Centennial History, 52; Unknown, “In memoriam of Dr. Nathan Barrows” (1900), Text Materials of Central Florida, 696. https://stars.library.ucf.edu/cfm-texts/696; Angelica Garcia, “Nathan Barrows (1830-1900): Charter Faculty,” Olin Library Archives, Rollins College, https://lib.rollins.edu/olin/oldsite/archives/golden/Barrows.htm.