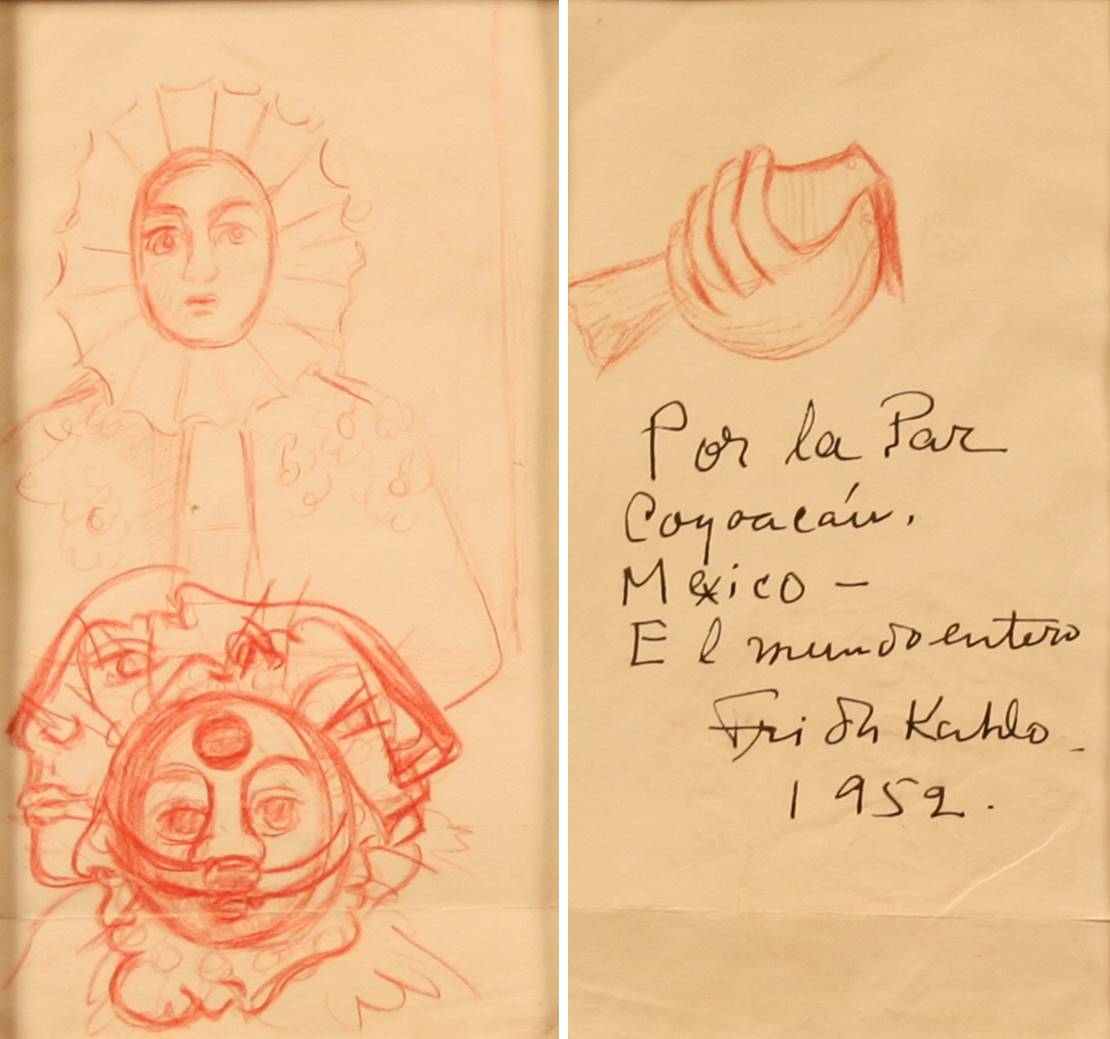

A small work by Frida Kahlo (Mexico, July 6, 1907–July 13, 1954) in the exhibition Mexican Modernity: 20th Century Paintings from the Zapanta Collection encapsulates so much meaning, and yet it looks so simple that it is easy to understate its historical significance. The two-sided drawing Por la Paz (For Peace) created in 1952 features the artist’s self-portrait in which she is represented wearing her signature Tehuana dress. (1) Below her image appear four figures in profile and frontal view. On the verso, a small vignette shows a hand holding a dove, a universal symbol of peace, and below the image are the words “Por la paz, Coyoacán, México—El mundo entero. Frida Kahlo, 1952.” This unassuming object, created with a color pencil and signed in ink, marks an important moment in Kahlo’s personal story and a historical juncture in which art played a significant role in social and political discourse.

In the early 1950s, the years leading to her death, Kahlo suffered numerous health complications; she was confined to a bed for lengthy periods of time and endured, among other procedures, several spinal surgeries. In 1953, her right leg was amputated; her physical and emotional health continued to deteriorate. However, while faced with these challenging circumstances, Kahlo never lost sight of her commitment to social justice and peace, and her unwavering loyalty to communist ideals informed her activism until her last day. On July 2nd, 1954, still recovering from pneumonia (and against doctors’ orders), Kahlo, along with her husband Diego Rivera, and other prominent artists, attended a demonstration to protest the American government’s intervention in Guatemala, which resulted in a military coup d’état and the removal of Guatemalan president Jacobo Árbenz, who had been democratically elected. (2) Kahlo attended the protest in a wheelchair and carried a large sign decorated with a white dove and the words “Por la paz.” This act “was her last public appearance, and Frida made herself into a heroic spectacle. As Diego pushed her wheelchair slowly through the bumpy streets, prominent figures in the world of Mexican culture followed in her wake.” (3) The phrase “Por la paz” alluded to the pursuit of peace, not only in Mexico and Guatemala but throughout the world. The protest was one of many massive demonstrations against US interventionism in Latin America. The Mexican government grappled with the reality that increased instability in their country could potentially lead to American military action in their soil in order to ensure security and order north of the border.

Kahlo kept abreast of the developments in Guatemala and Mexico’s response to the unfolding events. As early as 1952, the date of the drawing in our exhibition, there were news reports and rumors about the US government’s possible intervention in Guatemala. That same year, the Mexican government commissioned Diego Rivera to paint a mural for an international exhibition in Paris. The mural (painted only a couple of years after the start of the Korean War and now lost), The Nightmare of War and the Dream of Peace, was a statement for global peace and a commentary on war; it featured Kahlo in her wheelchair distributing copies of the Stockholm Appeal, which called for a ban on atomic weapons. Among the figures included in the painting were Joseph Stalin and Mao Zedong offering a peace treaty to the west, along with workers, peasants, and members of the military. One of the last works by Rivera, it was considered anti-American and to this day provokes much controversy and speculation.

With fist raised and her peace sign in hand, Kahlo used her visibility to mobilize members of the art community to protest interventionism in neighboring Guatemala. She used her platform to advance the causes she believed in and to give a voice and visibility to the marginalized. From her choice in attire to her declarations and statements and her appearance in Rivera’s controversial mural, Kahlo was determined to use every opportunity to raise awareness and promote peace. Kahlo died only a couple of weeks after the protest. This month, as we celebrate Kahlo’s birth and commemorate her departure from this world, we are reminded that small gestures often have historical longevity and that artistic expression is not created in a vacuum but instead reflects moments of upheaval and change, and embody the opportunity for transformation.

1 “The Tehuana dress comes from the Tehuantepec Isthmus, which is in the southeast part of Mexico in the state of Oaxaca. […] The Tehuantepec Isthmus is a matriarchal society, so that means women dominate the culture; they administer the society. Frida Kahlo didn’t just choose any dress from Mexico. She chose a dress that symbolizes a very powerful woman.” Hunter Oatman-Stanford, Uncovering Clues in Frida Kahlo’s Private Wardrobe in Collectors Weekly, accessed June 18, 2019. https://www.collectorsweekly.com/articles/uncovering-clues-in-frida-kahlos-private-wardrobe/.

2 President Árbenz had included members of the Communist Party in his cabinet, had started an agrarian reform that hurt the interests of the oligarchy and the United Fruit Company. In the eyes of the CIA and the Department of State these measures jeopardized the Hemisphere’s stability because they opened the door to Soviet influence.” Soledad Loaeza, “The Mexican Political Fracture and the 1954 Coup in Guatemala (The Beginnings of the Cold War in Latin America),” Culture & History Digital Journal, 4 (1), accessed June 26, 2019, http://dx.doi.org/10.3989/chdj.2015.006.

3 Hayden Herrera, Frida: A Biography of Frida Kahlo, (New York: Harper & Row Publishers), p. 429.