Forward written by: Ena Heller, Bruce A. Beal Director, CFAM

We are happy to introduce new insights into the museum’s American Art Collection. In our latest blog series, American Art Research Fellow Grant Hamming will share the results of his ongoing research into the Cornell Fine Arts Museum’s collection of American art. Dr. Hamming’s research is part of an initiative — funded by a generous grant from the Henry Luce Foundation — to maximize the potential of the collection to contribute to CFAM’s role as an academic art museum. Our goal is to make the collection more accessible to the Rollins, Winter Park, and Central Florida communities, as well as scholars and art lovers around the world. By the end of 2020, we aim to have images and interpretive text available online for the vast majority of the collection, which totals nearly 1,400 paintings, sculptures, photographs, drawings, prints, and other works of art. The project will also result in materials for the use of faculty at Rollins and other local colleges who wish to incorporate objects from the collection into their teaching, as well as a detailed analysis of the American collection, including its strengths, weaknesses, and biases, with an eye towards potential future acquisitions and exhibitions.

As we join together with our museum colleagues in facing challenges related to the Coronavirus (COVID-19), the staff at CFAM are sharing ongoing work, taking a fresh look at favorite art objects, and otherwise doing our utmost to continue to fulfill the museum’s mission. To see what else we’re up to, follow us on Instagram, Facebook, and Twitter.

Part 1: Connoisseurship, or When is a Stuart not a Stuart?

Author: Grant Hamming, American Art Research Fellow, CFAM

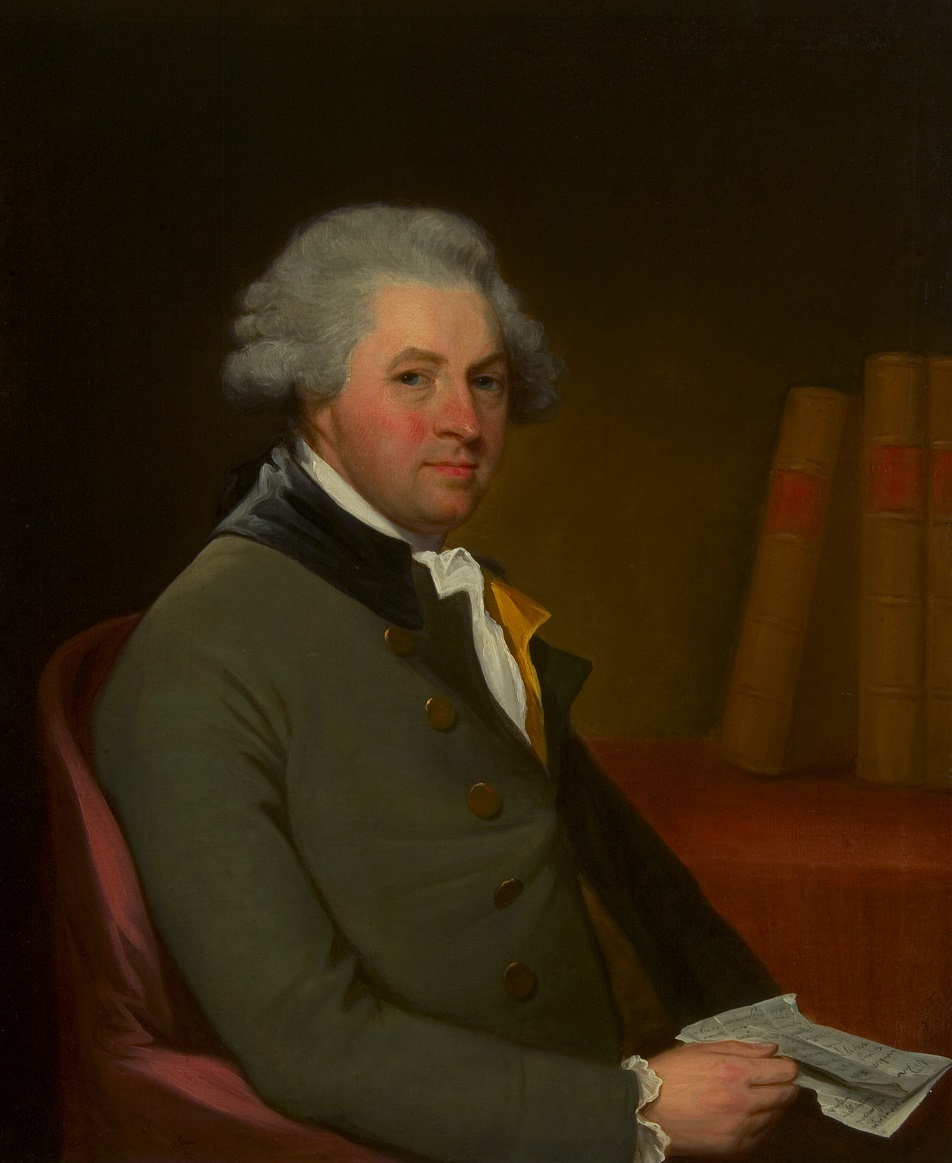

One of the most enigmatic paintings in the collection of the Cornell Fine Arts Museum is Gentleman in a Claret Coat (1960.13). This painting, which came to the museum in 1960 as part of a gift by the Myers family in honor of John C. Myers, Sr., has at times been attributed to Gilbert Stuart, but is currently listed in CFAM records as “after” the American master. The painting, which depicts a well-dressed man of the late 18th century, offers us a window into one of oldest and most arcane aspects of the art historian’s profession: connoisseurship.

You may be familiar with the term connoisseurship from its use in the appreciation of food and wine. A connoisseur is someone with expert knowledge and high levels of taste; an authority, in other words. In art history, the term carries a similar meaning, but with an added layer: Connoisseurship is the process by which a critic or art historian attributes a work to a particular artist, most often through an intimate, sometimes near-instinctual understanding of that artist’s style.1 Connoisseurship is not the only way that scholars determine the creator of a work. In fact, today it’s more like a last resort. Before turning to connoisseurship to attribute a work of art, a researcher will consult biographical information, historical auction records, letters, and other documentation; and the whole range of techniques, like X-rays and infrared light analysis, that fall under the umbrella of “technical art history.” But, absent a bill of sale, a signature, a letter, or even just an unbroken string of family ownership going back to the sitter, art historians are left to use the way an artwork — in this case a painting — is made in order to figure out who made it.

That brings us back to Gilbert Stuart. Stuart is one of the most famous painters in American history, having painted five presidents, including the renowned Athenaeum and Lansdowne Portraits of George Washington. He was also incredibly prolific, with more than 900 works currently attributed to him, virtually all of them unsigned.2 The CFAM collection includes another Stuart work, a portrait of Sir William Conyngham, an Irish aristocrat, politician, and scholar (2004.6). This painting is nearly identical to two other versions, held in the Irish National Gallery of Art in Dublin and Slane Castle, the Conyngham family seat. It is also reminiscent of a similar, slightly earlier work in the collection of the Norton Museum of Art in West Palm Beach. Since Stuart was known to make copies of his works, usually so patrons could hang them in multiple homes or give them to friends and family, the CFAM Conyngham is easily attributable to Stuart. The attribution of Man in a Claret Coat, however, is something else.

Stuart was also an erratic personality, demanding half payment for his portraits up front and frequently failing to complete them. When he left Dublin for New York, on the way to begin his series of Washington portraits, he left a number of unfinished canvases in his studio, prompting some of the patrons left behind in Dublin to wonder if he was a con artist.3 In fact, his propensity for erratic behavior of this sort was so notorious that his contemporaries advanced various theories as to its cause, including alcoholism or simple penury (Stuart and his wife had 12 children in all, and the family was constantly short of money). This vexing behavior has also resulted in a maddeningly inconsistent body of work.4 Unlike many artists, Stuart’s career does not show a logical progression, neither a slow but steady accumulation of skill nor a series of easily-defined stylistic periods (think of Picasso’s Rose, Blue, and Cubist Periods, for example). Instead, he would follow some of the finest work by any artist of his generation with half-finished, shaky, and poorly-drawn mediocrities. This tendency, along with the lack of documentation mentioned earlier, caused a number of high-profile battles over the legitimacy of certain Stuarts throughout the 20th century, with scholars arguing bitterly over whether a given portrait was or wasn’t a genuine Stuart, and even led some scholars to hypothesize a heretofore unknown studio assistant, an inferior, unnamed artist whose work Stuart sometimes passed off as his own for financial reasons.5

In her 2013 book, Gilbert Stuart and the Impact of Manic Depression, the scholar Dorinda Evans, whose earlier work The Genius of Gilbert Stuart is the basis of most current Stuart scholarship, advances a potential reason for this inconsistency.6 Evans argues, with evidence from Stuart’s surviving letters, recollections by friends and family of the history of mental illness in many of his descendants, and careful analysis of selected paintings, that the painter suffered from some form of bipolar disorder, an affliction which often caused him to be unable to work to a high level, sometimes for months at a time, but that also, during manic periods, propelled him to the height of his creative powers. Evans’ insights offer a tantalizing possibility: What if Man in a Claret Coat has been a genuine Stuart all along? We will likely never know, but Gilbert Stuart and the Impact of Manic Depression prompts us to take a fresh look at the painting, especially in comparison with Sir William Conyngton.

1 Svetlana Alpers. “Style is What You Make It,” in The Concept of Style, ed. Berel Lang (Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press, 1987), 139.

2 Dorinda Evans, Gilbert Stuart and the Impact of Manic Depression (Burlington, VT: Ashgate, 2013), 1.

3 Carrie Rebora Barratt and Ellen Miles. Gilbert Stuart (New York: Metropolitan Museum of Art, 2005), 78-9.

4 Barratt and Miles, 3-4. Evans, Gilbert Stuart and the Impact of Manic Depression, 1-2.

5 Evans, Gilbert Stuart and the Impact of Manic Depression, 1-3.6 Dorinda Evans. The Genius of Gilbert Stuart. (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 1999).

6 Dorinda Evans. The Genius of Gilbert Stuart. (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 1999).

Thanks for the soupçon of culture. Great idea. A break from Ozark😘‼️

I found this very interesting. Twelve children! Bipolar! It all makes sense, unfinished portraits.

A very interesting piece.