Over the past weeks, due to the killing of George Floyd by former Minneapolis police officer Derek Chauvin, America has been engaged in a national conversation about privilege, bias, and whose voices are heard in our country and its institutions. This has been most prevalent in terms of policing, but another recent focus has been the media, where Black staffers working at outlets from Bon Appetit to the New York Times have striven to make their voices heard about the biases they have faced as journalists. This has prompted many—myself included—to reflect on the unspoken assumptions that undergird the publications which help us make sense of the world. Though it has achieved a new urgency recently, this is by no means a new issue, a fact that is forcefully revealed by the revolutionary newspaper art of Emory Douglas.

Emory Douglas was born in Grand Rapids, Michigan, and moved to San Francisco with his mother when he was eight. Instead of the better life they envisioned, Douglas and his mother found themselves in a tiny, roach-infested apartment in the Fillmore, one of the few San Francisco neighborhoods open to Black people. Even then, Douglas and other Black children in the neighborhood were forced to wear dog tags to identify them as residents who had a right to be on the streets.1 As a young man Douglas took graphic arts classes at San Francisco City College. While making set designs for a production at San Francisco State University he met the playwright Amiri Baraka, a pioneer of the Black Arts Movement. Through Baraka he met Bobby Seale and Huey Newton, who had recently formed the Black Panther Party for Self-Defense, along with Eldridge Cleaver, another early leader in the Party.2 He participated in several of the group’s early actions, and was arrested along with the other leaders at an open-carry rally they held in Sacramento, the California state capital. One day, Seale was laying out the first issue of The Black Panther, the party’s newspaper, and Douglas offered to help. He quickly took over full control of the design of the paper—which would soon reach a weekly circulation of 300,000—and became the BPP’s Minister of Culture.3

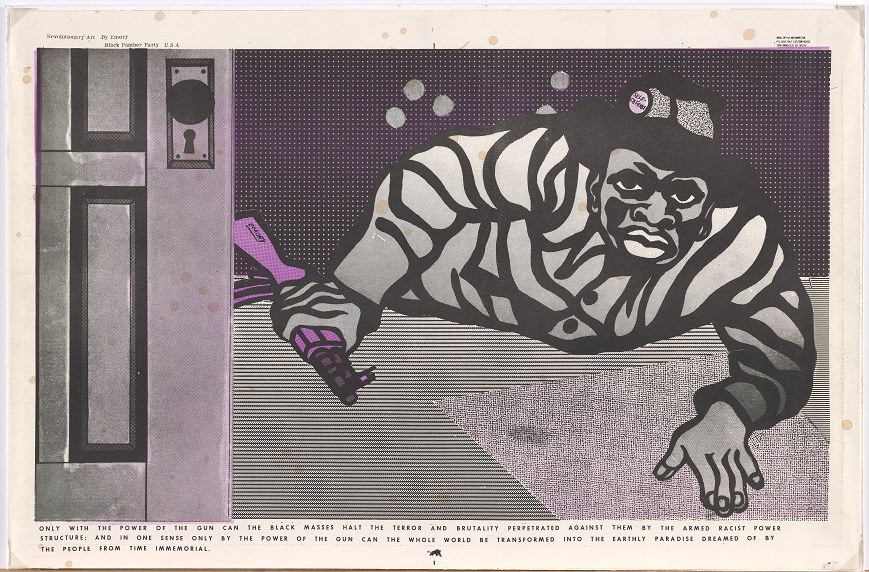

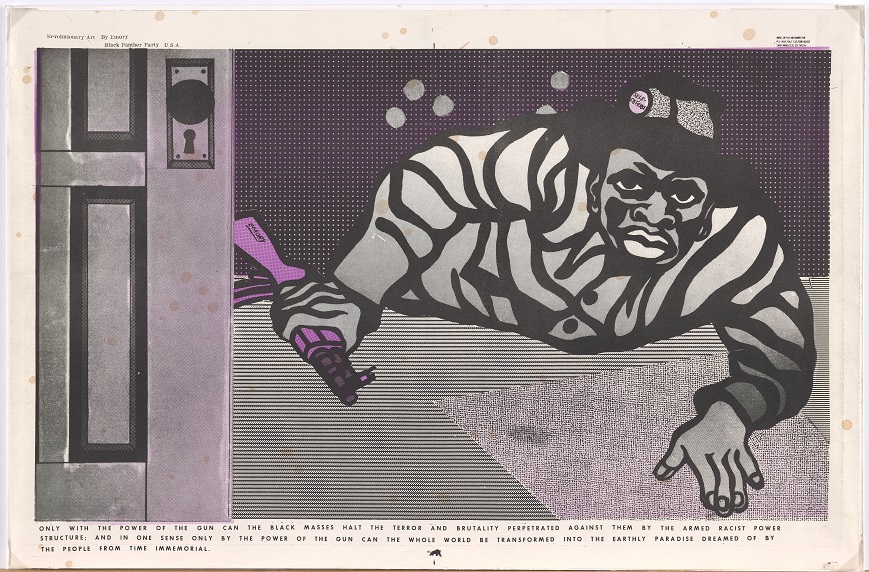

While at The Black Panther Douglas was responsible for a number of innovations, including weekly features which highlighted abusive Bay Area police officers.4 One of his most powerful was on the back page of the paper, which frequently featured a color poster devoted to radicalizing the paper’s Black readership with a combination of stark, easily legible imagery and revolutionary sloganeering that blended the aesthetics of the Black Arts Movement and propaganda posters from a variety of anti-capitalist, anti-imperialist revolutionary movements throughout the Global South. As the scholar Collette Gaiter notes, “Douglas’s stylized illustrations of dark-skinned, full-lipped, broad-nosed African-featured people visualized blackness in a way that was virtually absent from mainstream media in the 1960s.” These images, as shocking as they can seem even today, were designed to jolt African Americans out of their normal lives, to push them to exercise agency in a way that would inspire them to end their subjugation by mainstream society.5

These images are powerful on their own, but the fact that they were distributed in newspapers gives them even more rhetorical force. Douglas’s posters, distributed in a newspaper whose circulation was largely confined to inner-city ghettos, offer a pointed counterpoint to the sorts of imagery that circulated in mainstream newspapers with majority white audiences. They smolder with anger, but it is not a purposeless anger. He seeks, with works like Only with the power of the gun can the black masses halt the terror, to change his readers’ ways of thinking, to push them to envision themselves putting a stop to the grinding poverty and bleak violence visited upon them by the racist structures imposed by white society, newspapers included.

1 Baltrip-Balagas, “The Art of Self-Defense: In 1967, the Most Radical Graphic Expression in San Francisco Appeared Not in Pacifist Psychedelia but in the Revolutionary Design of Emory Douglas and the Black Panther Party.(Art Industry),” Print 60, no. 2 (2006): 87. Jo-Ann Morgan, The Black Arts Movement and the Black Panther Party in American Visual Culture (New York; London: Routledge, Taylor & Francis group, 2019).

2 Baltrip-Balagas, “The Art of Self-Defense: In 1967, the Most Radical Graphic Expression in San Francisco Appeared Not in Pacifist Psychedelia but in the Revolutionary Design of Emory Douglas and the Black Panther Party.(Art Industry),” 85–86.

3 Balagas, 86.

4 Morgan, The Black Arts Movement and the Black Panther Party in American Visual Culture, 147–48.

5 Colette Gaiter, “Visualizing a Black Future: Emory Douglas and the Black Panther Party,” Journal of Visual Culture 17, no. 3 (December 2018): 241–47