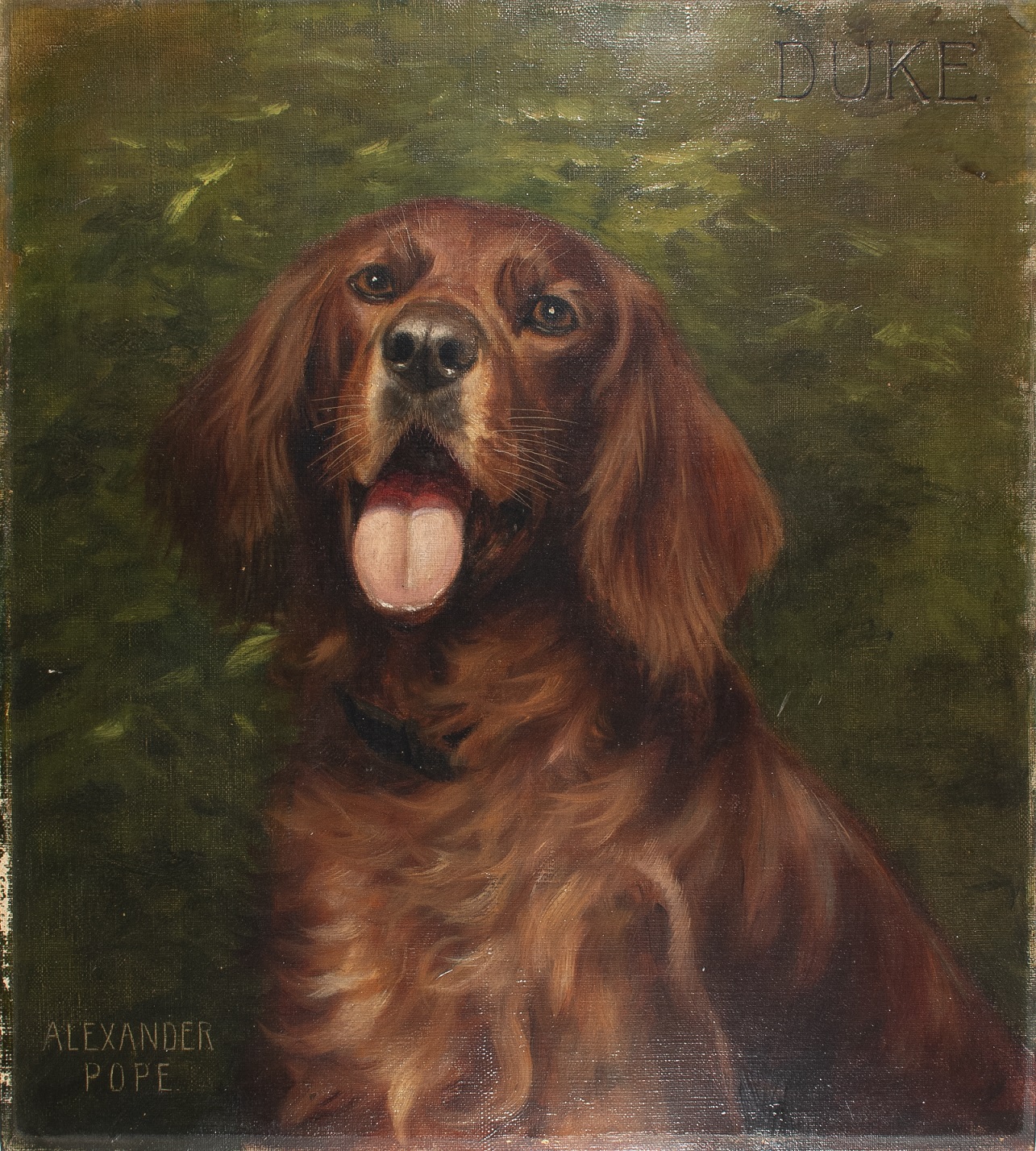

During the past months of lockdown, many of us have been spending a lot of time with our beloved pets. If you follow CFAM on social media, you may have seen an image or two of a staff member’s furry friend contemplating a work from the museum’s collection. As I write this, I am fresh off the experience of trying to maneuver my elderly miniature poodle, Chauncey, into looking like he was considering Andrew Moore’s 1999 photograph Campo Amor (Vista Este), Havana, Cuba. Chauncey clearly did not get the point of the exercise, or why I woke him from a nap to perform it, but he was happy to eat the treats I gave him for sitting just so. The experience caused me to reflect on one of the first works I encountered in my research at the museum, the American painter Alexander Pope’s Portrait of Duke, and the things it has to say about the long history of animal portraiture.

Pope is not widely known today, and when he is noted it is usually for the handful of still life paintings he made in the style known as trompe l’oeil. French for “fool the eye,” trompe l’oeil refers to paintings whose illusions are so precise that they literally trick the observer into believing the objects depicted are real. Originating with seventeenth century Dutch painters, the style had a revival in the United States in the waning decades of the nineteenth century, coinciding with the time when Pope was active as a painter in Boston.1 As a result of this association, Pope’s best-known work today is probably The Wild Swan, a 1900 painting found at San Francisco’s De Young Museum which depicts a freshly killed swan hung on a green door, waiting to be eaten, or perhaps turned into taxidermy. In his own time, however, Pope was much better known for his portraiture, in particular his paintings of animals. A lover of the strenuous, outdoor “sporting life” championed by luminaries such as President Teddy Roosevelt, Pope made his money making portraits of dogs and other thoroughbred animals, including sheep, cattle, and champion racehorses.2 In fact, he was so good at this line of work that he earned the title “The American Landseer,” after the famed British animal artist Sir Edwin Landseer, whose action-packed depictions of daring Alpine rescues set the standard for depictions of dogs in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries.3 Pope was so well known, in fact, that he was supposed to have painted a pair of portraits for Czar Alexander III of Russia, and also painted a trio of pictures for D.S. Hammond, the owner of the Plaza Hotel.4

Gift of Merrill J. and Ann Gross, 1995.18

This fame was ultimately somewhat fleeting. Pope was obscure enough that Merrill J. Gross, who gave the work to CFAM as part of a 1995 gift, was able to buy it in an antique shop in Peoria, Illinois in 1954, far from the Boston- and New-York-based galleries where Pope showed his work during his lifetime. As a result, we will likely never know more about the eponymous Duke, nor his owner’s reasons for having the Irish Setter immortalized by the premier animal portraitist of his day. The reason for that, I think, is that depictions of animals—especially portraits—exist uneasily in the world of fine art. There is always a sense of unseriousness about them, a way in which they reek faintly of bad taste.5 This is a shame, I think, because it can blind us to the ways in which people in the past actually felt about art, and how they used it to depict and make sense of their world. And, after all, is not one of the great joys of contemporary social media all the great pictures of cats, dogs, and other pets? This painting by Alexander Pope is evidence of the fierce love for—and pride in—someone once felt for their dog, as are the thirty-one photos I took this afternoon in search of that perfect image of Chauncey.

1 There has been a robust literature on trompe l’oeil in the United States since its rediscovery and popularization in the 1930s. For an overview of the major practiioners and the style’s rediscovery see Alfred Frankenstein, After the Hunt: William Harnett and Other American Still Life Painters 1870-1900 (Berkeley, Calif.: Univ. of Calif. P., 1975). Frankenstein classifies Pope as one of the “second circle” of followers of William M. Harnett, the most famous practitioner of the style. Frankenstein, 139.

2 Frankenstein, 139. Donelson F. Hoopes. “Alexander Pope, Painter of ‘Characteristic Pieces,’” The Brooklyn Museum Annual 8 (1966-7), 133-4.

3 Frank T. Robinson. “An American Landseer,” New England Magazine (January, 2891), 631-641.

4 Robinson, 631-5.

5 Anne Ronan. “Beauty and the Bestiary: Animal Art and Humane Thought in the Gilded Age.” Doctoral Dissertation, Stanford University, 2015.