I live in a smallish college town in the Blue Ridge Mountains, far from the bustling museum and gallery scenes of New York, Boston, and Washington, D.C., three places I have lived over the years. Still, D.C. is about four hours from me by train, and I had anticipated traveling there somewhat frequently this year, to facilitate my research into the CFAM collection, for my own research, and simply for pleasure. Obviously—as is the case for my plans to travel to Winter Park this month—I had to adjust to the changing circumstances of our current world. I, like most art historians, believe deep in my bones that there is no substitute for the direct, unmediated encounter with the work of art. Indeed in February, when it became clear that something big was going to happen, I made a quick day trip to Washington to catch True to Nature: Open-Air Painting in Europe, 1780-1870 and Degas at the Opéra at the National Gallery (and to eat at my favorite ramen restaurant) before everything shut down. That was my last trip out of town, and it looks like it will be so for the foreseeable future.

I have sorely missed these encounters with works of art, but as with so much in our current way of life, I have adjusted. That is until this morning, when I read a wonderful reflection on the career of Leo Amino by the critic and poet John Yau, writing for Hyperallergic. In it Yau writes movingly of the art world’s erasure of Amino’s life and career, and the way in which he refused to play the art world “game” in a way that would have brought him greater recognition, instead preferring to keep to himself, making his human-scaled polyester resin and wood sculptures in his apartment, rather than a studio.1 The essay—which is a review of an exhibition at David Zwirner—is illustrated with truly stunning photographs. Fifteen years ago, when I was an art history major in college, faculty were just making the transition from pink-tinged photographic slides to digital, and such photos would have been an absolute wonder. But as good as they are, these photographs also set off that familiar longing to see works in person.

(American, 1911-1989)

Triumphant Warriors, 1951

Mahogany

47 x 16 x12 inches

The Alfond Collection of Art and Rollins College

Gift of Barbara ’68

and Theodore ’68 Alfond 2017.15.13

As part of my research, I keep a running list of works which I want to make sure to examine in storage at CFAM. Amino’s Triumphant Warriors, which I wrote about briefly back in May, is definitely on that list, and Yau’s review has prompted me to return to it again. The sculpture is nearly four feet tall, something which I was aware of but perhaps had not considered fully—the photograph makes it seem smaller, as they so often do. This scale, at once intimate and commanding, seems to me to be inextricably tied to the work’s effect. As Yau notes, Amino never worked in the monumental scale that was so common for his contemporaries, like David Smith.2 And yet, four feet is not exactly small, either. A four-foot wood sculpture is designed to call attention to itself, to have a relationship not just with the mind and the eye, but with the body. I can’t wait to get back to Winter Park, to see the sculpture as Amino intended. I’ll walk around it, leaning in close, inspecting the details of the wood grain, the ways that the forms and negative spaces of the sculpture perfectly balance one another—or, perhaps, don’t. Then I’ll step far away from it, trying to get a sense of how it changes as I move around the room.

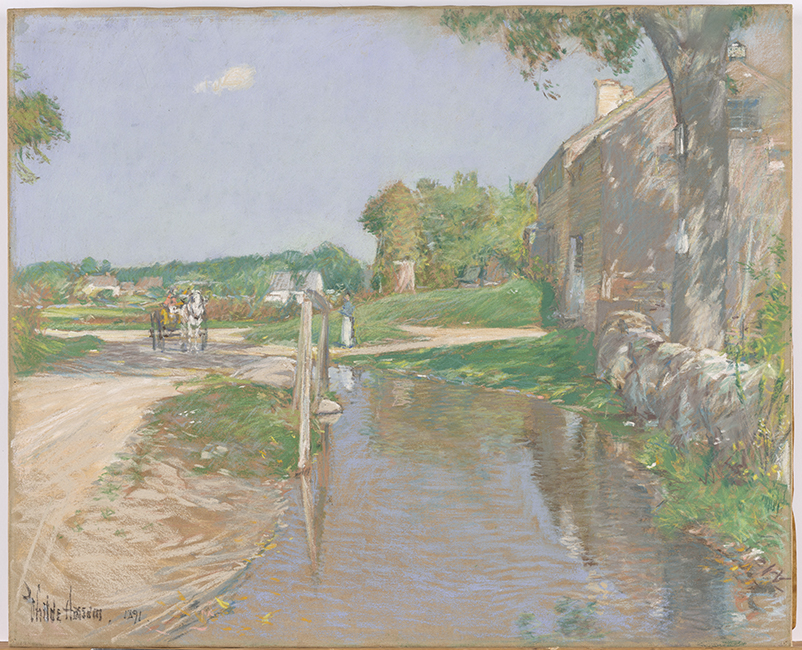

After that, perhaps I’ll step into the Siemens Print Study Room to consider Childe Hassam’s Country Road. This work is on a much different scale and demands different engagement from the viewer. It’s smaller, and two-dimensional. It demonstrates Hassam’s facility with pastel, a delicate medium that straddles drawing and painting, and goes back centuries. Pastels are wonderful—bright yet soft, they are perfect for representing sunny landscapes and lushly lit interiors. They have a fine, feathery texture that is virtually impossible to replicate on a computer screen, no matter how high-resolution the image. They are also incredibly fragile, with pigments that are quite prone to change in the light, and barely adhere to the (also fragile) papers to which they are applied.3 Any time you see an exhibition that features pastels, I recommend you go see these beautiful objects in person. It will be well worth your time. That’s why Country Road is at the top of my “to see” list for my next trip to Winter Park, especially since Hassam is an acknowledged master of the medium.4

17 5/8 x 21 1/4 in., Gift of Diane and Michael Maher, 2017.8.2

I don’t know when I’ll get to make that trip to Florida, or

to my favorite haunts in Philadelphia, Richmond, and San Francisco. But thanks

to Yau’s essay, I am reminded of why I became an art historian in the first

place, and why I think museums are some of the most special places in our

society. There is nothing like that encounter with the work of art, that

feeling of it reaching out to you, pulling you in for a closer look.

1 “The Art World’s Erasure of a Revolutionary Japanese-American Artist,” Hyperallergic, July 18, 2020.

2 “The Art World’s Erasure of a Revolutionary Japanese-American Artist.”

3 “French Pastels: Treasures from the Vault.” Museum of Fine Arts, Boston.

4 H. Barbara Weinberg, ed. Childe Hassam: American Impressionist. (New York: The Metropolitan Museum of Art, 2004), 126.