Sam Gilliam has long been one of the foremost American abstract painters, as well as one of the most successful African American artists. He was the first Black artist to represent the United States in the Venice Biennale in 1972.1 Yet, in the 1960s and early 1970s, when Gilliam first rose to prominence as a member of the Washington, D.C. Color School, the painter had an at-best uneasy relationship with the Black Power and Black Arts Movements, both of which were dominant forces in the cultural landscape of the time.2 In general, these movements were suspicious of non-representational art, which they viewed as overly intellectual, elitist, and out of touch with the lived experiences of Black people in the United States. Instead, they preferred the readily legible didacticism of artists like Emory Douglas, whose posters urged African American people to imagine a world in which they held greater political and cultural power.3 This was despite the fact that Gilliam had long been committed to Civil Rights, serving as a leader of the NAACP at the University of Louisville and participating in the March on Washington in 1963.4 Rather than publicly clash with the Black Arts Movement, Gilliam responded obliquely, making a series of works that incorporated his own clothing and personal effects, as if to literally inscribe his own personhood into the art.5 He also turned his public comments to museums, urging them to do more to cultivate Black audiences while simultaneously urging the African American community to show a greater appreciation for a wider range of aesthetic production.6

(American, b. 1933)

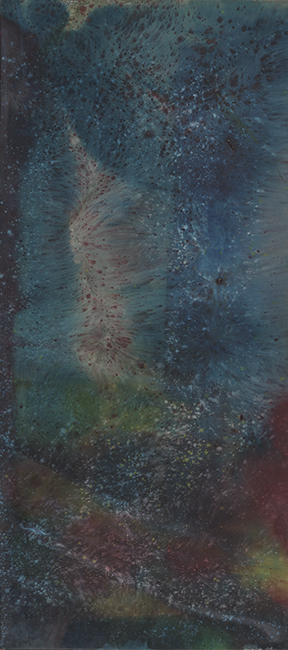

Blue and Red (And Again), 1967

Acrylic on Canvas

90 x 40 in.

Gift of Mrs. Elizabeth Phillips, 1997.17

© Sam Gilliam

More recently, as Gilliam has increasingly assumed the status of an elder statesman and as the Black Arts Movement has received renewed attention from critics and art historians, scholars have begun to reevaluate the relationship between Black abstract artists and their racial identities. Gilliam was one of a number of such artists working in the 1960s and 1970s, and he shared with many of them an interest in improvisation, in terms both formal and material.7 In works such as Red and Blue (and Again), Gilliam poured heavily diluted acrylic paints on raw, unprimed canvases, allowing the pigments to pool and swirl. He frequently left them to dry bunched haphazardly on the floor or hung from the ceiling, creating additional ripples and puddles of color.8 Gilliam has connected these works to the American South, in particular the river valleys near his hometown of Louisville, noting “Particularly in Kentucky, rivers constitute the most amazing, dynamic forces. They always flooded, and one was always conscious of them.”9 Further, he also relates his work to the quintessentially Southern—and Black—art forms of the blues and jazz, both of which involve significant amounts of improvisation. The artist Rashid Johnson, one of a younger generation of Black artists who were influenced by Gilliam and his contemporaries, sees this confluence of abstraction and improvisation as essential to Gilliam’s work. He remarks that instead of seeing Gilliam merely as a formalist, “I…think of Gilliam more often for his strength of character and his use of color as an activist tool.” Gilliam’s abstraction, for Johnson, is itself a radical gesture, a refusal to allow the circumstances of daily life to intrude upon his artistic vision. This radicality ties him to artists like James Baldwin and John Coltrane, two artists who also used abstraction—in their cases, linguistic and musical abstraction—to create emancipatory work that liberated both artist and viewer from the constraints of Black life in the 1960s.10

Johnson goes on to say that “For myself and countless

others, the work of Sam Gilliam has never disappeared from view.”11 Gilliam

has returned the favor, engaging frequently with the work and ideas of younger

generations of Black artists. His 2009 silkscreen Chakaia, also part of

the CFAM collection, demonstrates this engagement. Booker’s densely

constructed wearable sculptures and monumentally scaled works made of

shredded tires follow in Gilliam’s footsteps, a fact which he playfully

acknowledges in the work. The sculptural forms, massed in the middle of the

slightly-off-center work, suggest both Gilliam’s celebrated Drape

sculptures and the brightly massed colors of Booker’s work. In it, Gilliam—also

a longtime teacher in Washington, D.C., Baltimore, and Pittsburgh—signals his

ongoing engagement with abstraction, Blackness, and the art world writ large.

1 Sam Gilliam, The Music of Color. Sam Gilliam 1967-1973: Kunstmuseum Basel June 9-September 30, 2018, ed. Jonathan P. Binstock and Josef Helfenstein (Exhibition The Music of Color. Sam Gilliam 1967-1973, Köln: Verlag der Buchhandlung Walther König, 2018), 183.

2 Jonathan P. Binstock and Sam Gilliam, Sam Gilliam: A Retrospective (Berkeley : Washington, DC: University of California Press ; Corcoran Gallery of Art, 2005), 2–3.

3 Mark Godfrey et al., eds., Soul of a Nation: Art in the Age of Black Power (New York: Distributed Art Publishers, Inc, 2017), 165.

4 Binstock and Gilliam, Sam Gilliam, 7–11.

5 Binstock and Gilliam, 3.

6 Binstock and Gilliam, 65–66.

7 Godfrey et al., Soul of a Nation, 165–66.

8 Gilliam, The Music of Color. Sam Gilliam 1967-1973, 33.

9 WILLIAM FERRIS, “Sam Gilliam: 1933–,” in The Storied South, Voices of Writers and Artists (University of North Carolina Press, 2013), 202.

10 Gilliam, The Music of Color. Sam Gilliam 1967-1973, 174.

11 Gilliam, 175.