This article was originally posted on February 2, 2021 by Grant Hamming.

Recently I wrote about the changing taste for American modernism, and the impact these changes had on the career and legacy of the painter Ilya Bolotowsky. As I was researching Bolotowsky, I learned about his involvement in the group American Abstract Artists, of which he was a cofounder, and his more general involvement in advocating for abstraction during a time when the American art scene was dominated by Regionalism and other figurative styles. I was aware, while I was reading about Bolotowsky, that the AAA featured another Russian-born artist, Esphyr Slobodkina, but none of the sources on him mentioned how close the two painters were. In fact, Bolotowsky and Slobodkina were married from 1933-38, though she rarely comes up in the scholarly literature on him.1

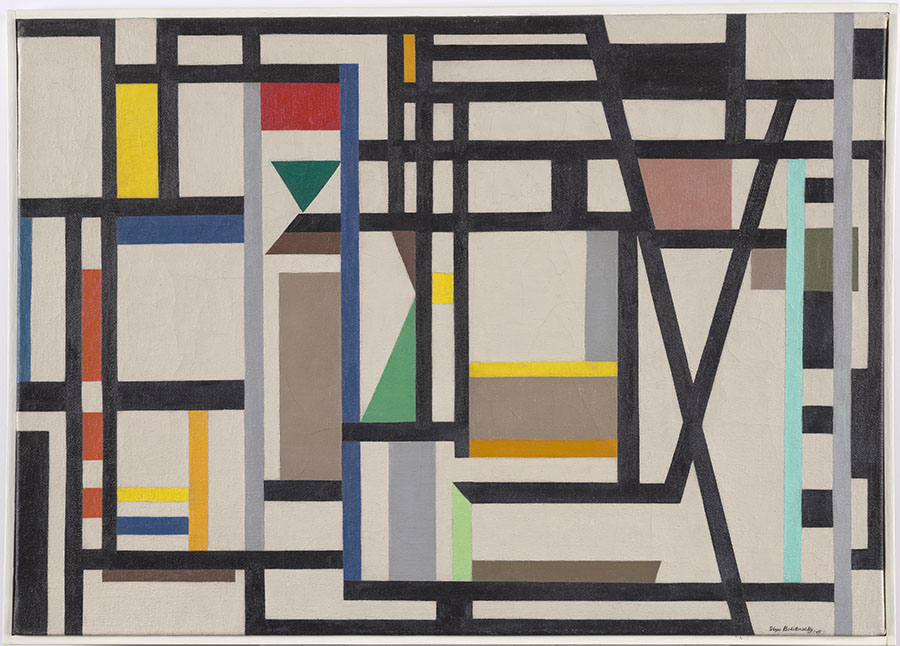

18 x 22 in., The Alfond Collection of Art, Gift of Barbara ’68 and Theodore ’68 Alfond, 2017.15.5. Image courtesy of the Slobodkina Foundation, Northport, New York

I probably should not have been so surprised. The history of American art is full of male painters and their less prominent wives: Jackson Pollock and Lee Krasner; Elaine and Willem de Kooning; Carl Andre and Ana Mendieta…and Rosemarie Castoro. Yet, despite this historical blindness for the work of women artists, a comparison of the two Russian emigres yields rich insight into the situation of abstraction in the United States just before the heyday of Abstract Expressionism.

Slobodkina and Bolotowsky

Slobodkina and Bolotowsky met in 1931, though they had both been attending the National Academy of Design together since 1928. They initially bonded over their shared distaste for the school and its staid, academic (as opposed to modernist) curriculum. They became close friends, and, after Bolotowsky returned from a trip to Europe full of news of the latest advances in European modernism, she prevailed on him to become her teacher, later remarking that he was a “walking encyclopedia” of knowledge who “stressed the organization of a painting—its form, color, and space—and illustrated his points with examples from old masters as well as modern artists.”2 The two married in 1933, after which Slobodkina quit the NAD and became a professional artist. By 1935 they had separated—the marriage may have been more for immigration purposes than a true romance—though they remained friends and close colleagues for many years after.3

Slobodkina’s Signature Style

In the previous entry, I noted Bolotowsky’s indebtedness to the neo-Plasticism of Dutch artist Piet Mondrian, who moved to the United States after the Nazi invasion of Paris. Slobodkina also held Mondrian in high esteem, but her work is much less dogmatic in its approach than Bolotowsky’s. In fact, she blended Mondrian’s geometric approach with the more biomorphic one of Spanish abstract Surrealist Joan Miró, juxtaposing her sharper-edged forms with a series of thinner, more curved ones laid atop them. In fact, she developed this sweeping curve as something of a signature style, adopting Mondrian’s concept of “dynamic equilibrium” without copying it.4 This approach led to the critic Clement Greenberg—then still relatively young, and not yet the dominant presence in the art world that he would become—to declare her one of the better entrants in a 1942 Abstract American Artists group show that he mostly dismissed.5 Indeed, as the curator Sandra Kraskin has noted, it was Slobodkina’s unique approach and pugnacious unwillingness to compromise on it that defined her as an artist, and she remained a notable figure in the art world even after moving out of Manhattan to Long Island, and then later to Hallandale, Florida.6

Slobodkina: Author / Illustrator

Ultimately, Slobodkina is probably best remembered for her 1940 children’s book Caps for Sale, which has remained continuously in print for the last 80 years.7 Her work as a painter—as well as an advocate and administrator, including a stint as the president of the Abstract American Artists—was equally influential, and I am delighted to have spent some time getting to know her.

1 Sandra Kraskin, “Esphyr Slobodkina: A Pioneer of American Abstract Art,” in Rediscovering Slobodkina: A Pioneer of American Abstraction, First edition (Manchester, Vt: Hudson Hills Press, 2009), 20.

2 Slobodkina quoted in Kraskin, 17–20.

3 Kraskin, 20, 25.

4 Kraskin, 30–34.

5 Kraskin, 34. Late in his life Greenberg admitted that he had been too hard on the American Abstract Artists more generally, expressing a greater appreciation for the group and its work.

6 Kraskin, 42–46.

7 John Dorfman, “The Maker From Abstract Painting and Sculpture to Children’s Books and Architecture, Esphyr Slobodkina Could Do Just about Anything,” Art & Antiques 43, no. 1 (2020): 80.

The Rollins Museum of Art features rotating exhibitions, ongoing programs, and an extensive permanent collection of over 6,000 objects that spans centuries, from examples of ancient art and artifacts to contemporary art. Open to the public year-round, its holdings include the only European Old Master paintings in the Orlando area, a sizeable American art collection, and a forward-thinking contemporary collection on view both at the Museum and The Alfond Inn.