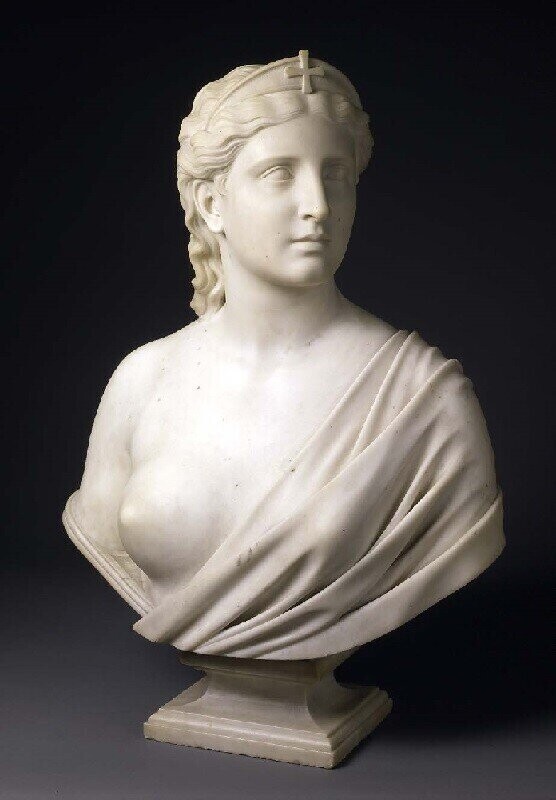

Hiram Powers

(American, 1805-1873), Faith, ca. 1867, white seravezza marble, 29 in. x 20 in. x 12 in. sculpture, Gift of Hiram Powers II, grandson of the artist and Rollins College professor 1976.31

Hiram Powers was celebrated during his time as the foremost American sculptor, lauded for bringing the dominant Neoclassical sculptural style to the United States. Powers—who was born in Vermont and spent his formative years in Cincinnati—moved to Florence in 1837, drawn by the presence of high-quality marble and workmen with long experience in shaping it. In 1843 he made The Greek Slave, a semi-allegorical representation of a bound young Greek woman from the time of the Greek Revolution. Playing into racist and Orientalist stereotypes about supposed Turkish barbarism, the sculpture caused a sensation in the United States, where it drew huge crowds, scandalizing viewers who were uncomfortable with nudity in art. The Greek Slave is widely credited with normalizing a certain kind of classical female nudity in American art. It also catapulted Powers to new heights of fame, turning his Florence studio into a must-visit for American and British tourists in Italy. While there, they could sit for a portrait bust by Powers or purchase a copy of one of several allegorical sculptures including this one, Faith, representing a generalized ideal that appealed to many of Powers’ wealthy patrons.

Already by the time of his death in 1873 Powers was falling out of popular favor, with audiences in both Europe and the United States coming to prefer more naturalistic work by sculptors like Augustus Saint-Gaudens and Auguste Rodin, the latter of whom is the foremost figure in the development of sculptural modernism. As a result, Neoclassicism has come to seem bland and sterile next to the emotional dynamism and formal innovations of the twentieth century. Sculptures such as these, however, are valuable for the windows they provide into the mindset of the dominant white Protestant culture of the nineteenth century. Powers, like many of his contemporaries, was simultaneously uneasy with and drawn to the nude body. In order to resolve this tension, he relied on his Swedenborgian beliefs. Swedenborgianism, also called the New Church, was a religious movement based on the beliefs of eighteenth century Swedish clergyman and mystic Emanuel Swedenborg that gained widespread currency in Europe and the U.S. during the nineteenth century. Swedenborgians believed, among other things, in the unity of the soul and the body. This belief allowed Powers to justify his use of nudity through the pursuit of the perfect body, the proper representation of which would help viewers towards an understanding of spiritual purity.

Powers was well known for his perfectionism, rejecting sculptures in which the marble showed even the smallest dark spots or other imperfections. This quest for a pure whiteness was tied to his New Church beliefs, and it was also something of a personal brand. It is also inescapable, however, that Powers made Faith and similar sculptures during the run-up to and aftermath of the Civil War, giving his quest for pure whiteness a decidedly racial cast. Powers was not an abolitionist—a cautious and conservative man, he considered the movement socially dangerous, though he opposed slavery as a general moral principle. The Greek Slave was nonetheless taken up as a symbol by many abolitionists, who found the figure’s Christian modesty useful in their rhetorical campaign against American slavery. Yet it is also the case that Powers’s—and his colleagues’—emphasis on the purity of white marble itself has a racial dimension. By insisting that only the purest white marble can represent the perfect body—and thus the perfect soul—Powers implicitly, if not intentionally, helped set the boundaries for inclusion in the American spiritual and political community. He was neither the first nor the last to participate in the equation of whiteness with purity or moral rightness, but his work offers us the opportunity to consider other unspoken assumptions which underlie seemingly innocuous works of art.

Grant Hamming, Ph.D.

American Art Research Fellow

Read more about Hiram Powers’ work on our Collection page.