A few weeks ago, I wrote about the painter Wolf Kahn’s dramatic escape from Germany on the eve of World War II. This week, I came across a similar story, this one from Kahn’s slightly older colleague Richard Lindner. Lindner, who was born to a German-Jewish father and an American mother in Hamburg in 1901, grew up in Nuremberg, eventually becoming a successful commercial artist in Munich and then Berlin. He especially loved Berlin, which during the Weimar years was a center for a freewheeling café culture that Lindner described as fantastic, scandalous, decadent, and even sinister. The rise of Adolf Hitler and the Nazi Party in 1933 caused Lindner to leave Germany almost at once. Lindner lived in Paris from 1933 to the German invasion of France in 1940, when he was interned by the French government alongside other German nationals. He escaped the internment camp by enlisting in the French Army. Soon accused of being a German spy, narrowly escaping execution before fleeing on foot across the French border with Spain, he eventually ended up in Lisbon, where he got a ticket to the United States based on his American ancestry. He arrived in New York on March 17, 1941.1 Lindner immediately took to New York, treasuring it and other American fantasylands like Disneyland and Las Vegas.2 Once he was in New York, Lindner continued to work as a commercial illustrator before finally achieving his desire to become a painter in middle age.3 As he did so, the city became his primary subject matter, and he represented it as a colorful, madcap, funhouse version of itself.

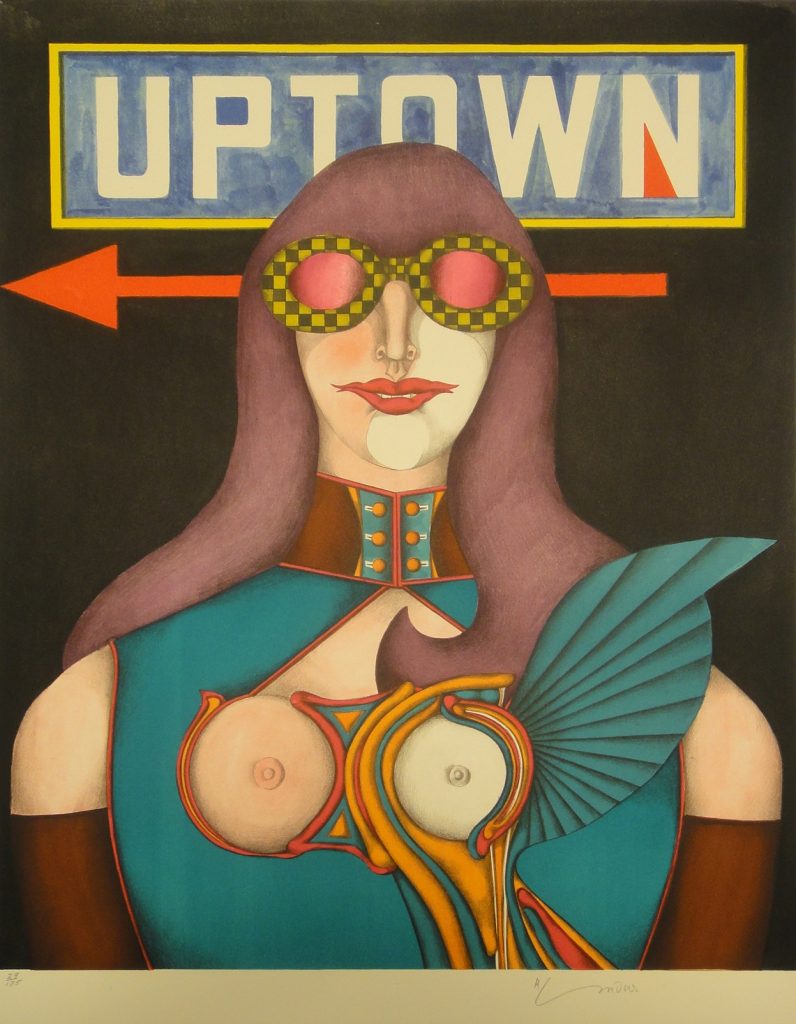

CFAM is home to a number of lithographs Lindner made after his transition to painting, part of a broader turn by American postwar artists to the medium, which lent itself well to the painterly line and intense color favored in those decades.4 In particular, his Fun City portfolio of 14 lithographs shows his vision of the city, which was shaped by his memories of the German neue Sachlichkeit (New Objectivity), which used acid sarcasm to deflate the preening pretensions of the cultural and financial grandees of Weimar Germany. Lindner remarked that “My work is really a reflection of Germany of the ’20s. It was the only time the Germans were any good. On the other hand, my creative nourishment comes from New York and from pictures I see in American magazines and on television. America is really a fantastic place.”5 In St. Mark’s Place, Lindner represents the famed East Village street with one of its famously eccentric denizens, in this case a wildly dressed man who walks a rooster on a leash. Uptown recreates the tiled signage inside of the subway, accompanied by a bizarre female figure whose abstracted breasts brazenly confront the viewer, acting as surrogates for the eyes which are obscured by her huge novelty sunglasses. Lindner particularly enjoyed these female figures, which he named Lulu after a character in works by the German playwright Frank Wedekind.6 He was fascinated by modern American women, whom he admired for their strength, once commenting that “The woman is the stronger, she is geared towards giving the man his lumps of sugar, as long as she gets something for them. But now, at the end of the 20th century, she wants to keep the sugar for herself.”7

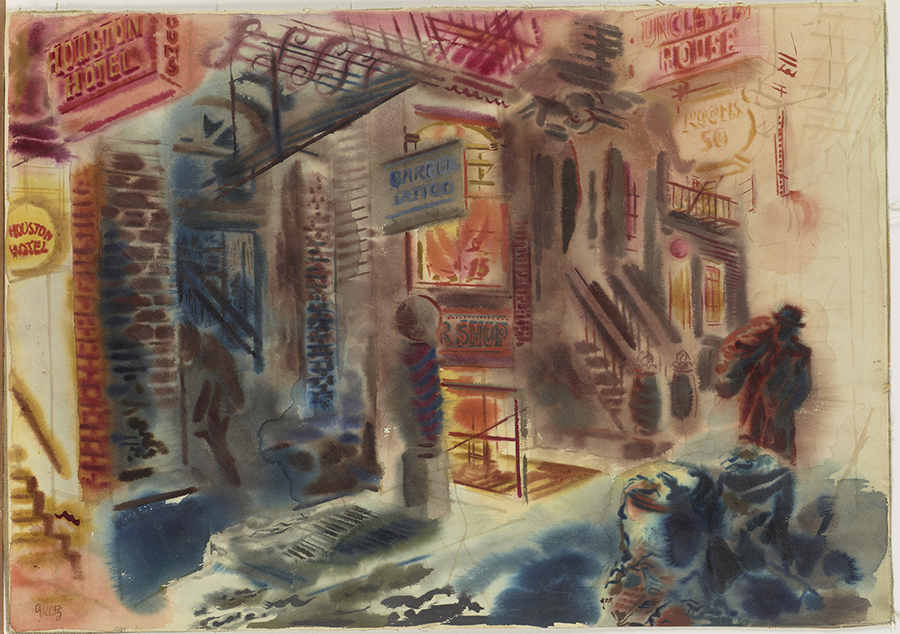

These works invite comparison with City Lights by Georg Grosz, one of the luminaries of the neue Sachlichkeit that was such an influence on Lindner. If the younger artist embraced New York and America, Grosz—who like Lindner had fled the Nazis, ending up as a teacher in New York—was not so sure about his adopted home. In the slightly earlier City Lights he paints Houston Street, just a few blocks from St. Marks Place. In this work the younger painter’s wild celebration is nowhere to be seen. Instead, Grosz represents the bright downtown lights as sinister and oppressive, washing out the forms of the buildings. Instead of bright, cheerful lunacy, Grosz’s New York is grim and melancholy, populated by dark, faceless figures and overflowing garbage bins. It is not clear whether the two artists—so similar in much of their biographies—were associates in New York, though Grosz died just as Lindner’s fame as a painter was really starting to take off. What is clear is that, despite their confluences of biography, the two men had very different reactions to the bustling metropolis.

While it is yet to be formally announced, look for an

exhibition of Lindner’s Fun City portfolio on the walls of the museum in

Summer 2021!

1 Thomas Levy et al., eds., Richard Lindner: Großstadtzirkus | Big-City Circus | Le cirque de la grande ville ; [anlässlich der Ausstellung Richard Lindner – Großstadtzirkus|Big-City Circus|Le Cirque de la Grande Ville, 06.02.2015 – 19.04.2015, Stiftung Ahlers Pro Arte/Kestner Pro Arte, Hannover (Ausstellung Richard Lindner – Großstadtzirkus|Big-City Circus|Le Cirque de la Grande Ville, Bielefeld: Kerber, 2015), 90–93. Lindner was something of a fabulist who enjoyed telling exaggerated or misleading tales about his life, but the basic outlines of his story have been corroborated by historians.

2 P. Selz, “The Work of European-American Artist Richard Lindner,” Art & Antiques. 32, no. 5 (2009): 60.

3 Robert Storr, The Museum of Modern Art, and Modern Art Despite Modernism, eds., Modern Art despite Modernism: Museum of Modern Art, New York (March 16 – July 26, 2000), MoMa2000 (Exhibition Making Choices: Modern art despite modernism, New York: Museum of Modern Art, 2000), 86.

4 Jennifer Quick, Jennifer L. Roberts, and Harvard Art Museums, eds., Jasper Johns/in Press: The Crosshatch Works and the Logic of Print (Cambridge, Massachusetts: Harvard Art Museums, 2012), 17.

5 Lindner quoted in Selz, “The Work of European-American Artist Richard Lindner,” 60.

6 Selz, 58.

7 Lindner quoted in Richard Lindner and Belinda Grace Gardner, Richard Lindner: Zeichnungen: {Drawings}, ed. Thomas Levy, 1. Auflage, Kerber Art (Ausstellung Richard Lindner – Zeichnungen / Drawings, Bielefeld Berlin: Kerber Verlag, 2016), 7.