This post is from October 2019. Cornell Fine Art Museum is now Rollins Museum of Art.

The following is an excerpt from Dr. Deborah Prosser’s essay included in the booklet that accompanies the Ut Pictura Poesis: Walt Whitman and the Poetry of Art exhibition on view at the Cornell Fine Art Museum from September 20 through December 29, 2019. ************* In the first stanza of the 1892 version of “Song of Myself”, Walt Whitman wrote: I celebrate myself, And what I assume you shall assume, For every atom belonging to me as good belongs to you. In 2019, 200 years after his birth, we all celebrate Whitman. In Philadelphia, Pennsylvania and Camden, New Jersey where the poet lived and worked for part of his life, at least 65 institutions and organizations are holding events in his honor. Whitman’s birthplace, now an historic house museum in Huntington, New York, is hosting an international conference for the anniversary of his birth. New York City’s Morgan Library and Museum is hosting the exhibition, Walt Whitman: Bard of Democracy1. In Winter Park, Florida, far from Whitman’s northeastern roots, curators, administrators, and librarians at Rollins College recognized a need to bring the poet into the limelight through the work of contemporary artists he inspired. Why? While bicentennial celebrations are ingrained in the United States cultural ethos due to the watershed of 1776, and Whitman’s work gained acceptance into the literary canon over the course of the twentieth century, such factors only guide and do not fully explain the entrenched and widespread interest in celebrating the poet this year. Those of us focusing our attention on Whitman are taking advantage of the demarcation a milestone birthday presents but, in fact, the poet does not need resurrection. His work is never far from the surface of literary, artistic, film, and popular culture—it endures. Walt Whitman continues to resonate because many of his most famous writings simultaneously validate both individuals and groups; espouse the value of a strong sense of self and also of being part of a whole. In “One’s Self I Sing”, the poet sang “a simple separate person, but also “the word En-Masse”. Whitman belongs to the masses and continues to inspire because his art is about belonging.

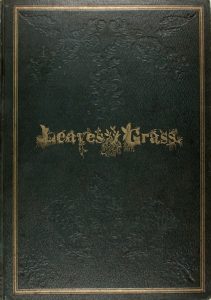

Leaves of Grass, First edition, 1855

Authored and bound by Walt Whitman, New York

William Sloane Kennedy Memorial

Collection of Whitmaniana, Rollins

College Archives and Special Collections

Whitman in referring to his photographs said, “there is a new Walt Whitman every day”2. The phrase is prophetic, as indeed is much of Whitman’s writing, because contemporary scholars espouse that each generation invents a new Whitman for a new era3. Whitman is famously and consistently heralded as simultaneously the poet of the individual and the poet of democracy. He endures because he is not simply a white male author with a seat in the canon, but rather because he invites his readers to find their own identity and voice within an American identity. As Whitman scholar Scott MacPhail notes, Whitman’s “work initiates a new national literature and articulates an American identity by grounding the national in the lyric’s promise of an authentic and representative human voice”4. The poet through expressive means invites his readers to find their own voice, their own identity, their own audience, their own influence5. Whitman remains powerful because he forges a relationship with his readers by both instructing and inviting them. “Remember my words, I may again return,” he advises in “So Long!”, and in “Song of Myself” he tells readers, “I stop somewhere, waiting for you”6. Many of Whitman’s works continually return to the theme of joining him by finding one’s own voice. This in part is why his poetry has appealed to visual artists, such as those in Ut Pictura Poesis: Walt Whitman and the Poetry of Art, who work to develop their own unique visual style and interpretive influence within their oeuvres.

1See www.Whitman@200.org; www. Walt200.org; https://www.themorgan.org/ exhibitions/walt-whitman

2Quoted in Ed Folsom, ed., Whitman East & West (Iowa City: University of Iowa Press, 2002), xv.

3Folsom, xiv.

4Scott MacPhail. “Lyric Nationalism: Whitman, American Studies, and the New Criticism.” Texas Studies in Literature and Language 44, no. 2 (2002): 136, https://muse. jhu.edu/ (accessed July 11, 2019).

5For a further reading on literary voice, see Donald Wesling and Tadeusz Slawek, Literary Voice: The Calling of Jonah (Albany: SUNY Press, 1995).

6Quoted in Anton Vander Zee. “Inventing Late Whitman.” ESQ: A Journal of Nineteenth-Century American Literature and Culture 63, no. 4 (2017): 642, https://muse.jhu.edu/ (accessed July 11, 2019).