In recent years, museum professionals have been focusing on how to decolonize museum practice. Colonialism is deeply embedded in museums through the way collections are formed and how museums categorize, exhibit, and disseminate the history of their collections. Decolonizing, though an extensive and imperfect process, can be carried out in many ways as mentioned in Elizabeth Merritt’s Confronting the Past: The long, hard work of decolonization in the American Alliance of Museum’s Trendswatch 2019. As trusted institutions, museums recognize their influential position to alter existing power structures, create more inclusive and equal organizations, prioritize sharing marginalized histories, and ultimately help lift Indigenous communities and keep their histories in the public consciousness.1 Of late, the Cornell Fine Arts Museum (CFAM) at Rollins College has been researching and planning ways to participate in decolonizing museum practice.

Early American Photographs from the Collection

CFAM holds a small collection of photographs depicting Native populations from the late nineteenth and early twentieth century. Viewers must approach these photographs with a critical eye and consider the role of the photographer, the subject, and the audience during the time of their creation. These photographs were taken in the era of Manifest Destiny, a term coined in 1845 to describe the belief that the United States was destined by God to expand westward to the Pacific Ocean. This ideology was leveraged to justify the forced evacuation and violence towards Indigenous peoples not conforming to the democratic and capitalist system. Most of the photographs of the Native population taken during this time were the following: “the early studio portrait, the religious conversion document, the boarding school or reservation view as visual evidence of assimilation, the commercial portrait taken in a nostalgic setting, and the ethnological recording device.”2 Each type of photograph, though visually varied and produced with different intentions, operates in a similar way to support the notions of Manifest Destiny and perpetuate a romanticized vision of Indigenous lives.

Studio and Commercial Portraits

Photography studios during the late nineteenth century and early twentieth century frequently utilized staged backdrops, costumes, props, and favored poses for their sitters. Those choices, a collaboration between the sitter and photographer, often signified a certain social status to viewers. The studio portraits of Native peoples participate in those traditions, but also reveal a deeper, more complex history. Their photographs were not only taken for personal record, but were also often replicated and sold as stereographs, cabinet cards, and postcards as some of the many forms of memorabilia generated to appease the American public’s growing interest in “Indian novelties.”3 The photographs by D.F. Barry, Gertrude Käsebier, Frank Rinehart, Lenny and Sawyers, and Henry Beuhman in CFAM’s collection serve as examples of studio and commercial photographs that commodified these figures from history.

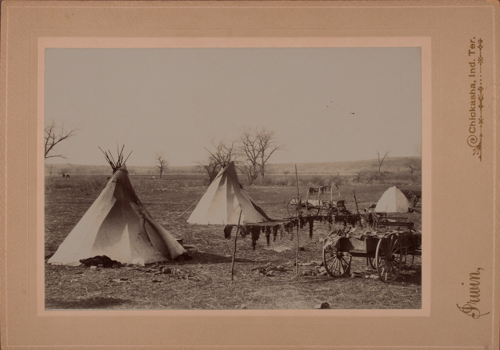

Ethnological Photographs

The increased interest in collecting photographs was in part due to Edward S. Curtis’s popularly known The North American Indian which addressed the Native population as a “vanishing race.”4 It generated nostalgic feelings for a culture viewed by the public as a thing of the past. As an ethnographer, a scientist who studied the customs of individual peoples and cultures, Curtis set out from 1907–1930 to create the forty-volume edition of photographs and texts that would record all aspects of Native life.5 The photograph by Curtis from this study as well as the work by William E. Irwin in CFAM’s collection — originally intended to educate European and American audiences — now raise questions about accuracy and agency. These photographs were also widely reproduced and sold to the public, blurring the distinctions between photographs taken for scientific study and commercial practice.6

Enduring Perceptions

Despite the differing intentions of these photographs, their result remains the same. They dominate the visual history of the Indigenous population from that era and subsequently serve as the main reference for future use in everyday visual culture. Thus, these images perpetuate the imagined, outsider perspective and harmful stereotypes that now persist in film, television, marketing, and sports.7 It is now the responsibility of current cultural institutions to confront past and present inequities and decolonize these long-established practices.

In the context of current research and decolonizing efforts by museums nationwide, CFAM has looked critically at its programming, exhibitions, educational content, and collections. Recent acquisitions include the works by artists Jaune Quick-To-See Smith and Jeffrey Gibson. The work by Jaune Quick-To-See Smith is currently on view in CFAM’s The Place as Metaphor: Collection Conversations exhibition, and on February 26th at 6:00 p.m., the artist will present her talk titled A Survey of Contemporary Native Art at Rollins College Bush Auditorium.

1Elizabeth Merritt, “TrendsWatch 2019: Confronting the Past: The long, hard work of decolonization” (Center for the Future of Museums Blog AAM, 2019). https://www.aam-us.org/2019/04/19/trendswatch-2019-confronting-the-past-the-long-hard-work-of-decolonization/.

2 Carolyn J. Marr, “Taken Pictures: On Interpreting Native American Photographs of the Southern Northwest Coast” (The Pacific Northwest Quarterly 80, no. 2, 1989), 59-60. www.jstor.org/stable/40491037.

3 Carolyn J. Marr, “Taken Pictures: On Interpreting Native American Photographs of the Southern Northwest Coast” (The Pacific Northwest Quarterly 80, no. 2, 1989), 55. www.jstor.org/stable/40491037. And American Antiquarian Society, “Photographs of Native Americans,” Accessed November 15, 2019. https://www.americanantiquarian.org/nativeamericanphotos.htm

4 Allison C Meier, “Native Americans and the dehumanizing force of the photograph,” (Wellcome Collection, 2018). https://wellcomecollection.org/articles/WrUTGh8AACAA1FH8

5 Shannon Egan, ““Yet in a Primitive Condition”: Edward S. Curtis’s North American Indian” (American Art 20, no. 3, 2006), 59. doi:10.1086/511095.

6 Claire Voon, “A Rare Collection of 19th-Century Photographs of Native Americans Goes Online,” (Hyperallergic, 2018). https://hyperallergic.com/434729/19th-century-photos-native-americans-american-antiquarian-society/

7 Allison C. Meier, “Native Americans and the dehumanizing force of the photograph,” (Wellcome Collection, 2018). https://wellcomecollection.org/articles/WrUTGh8AACAA1FH8