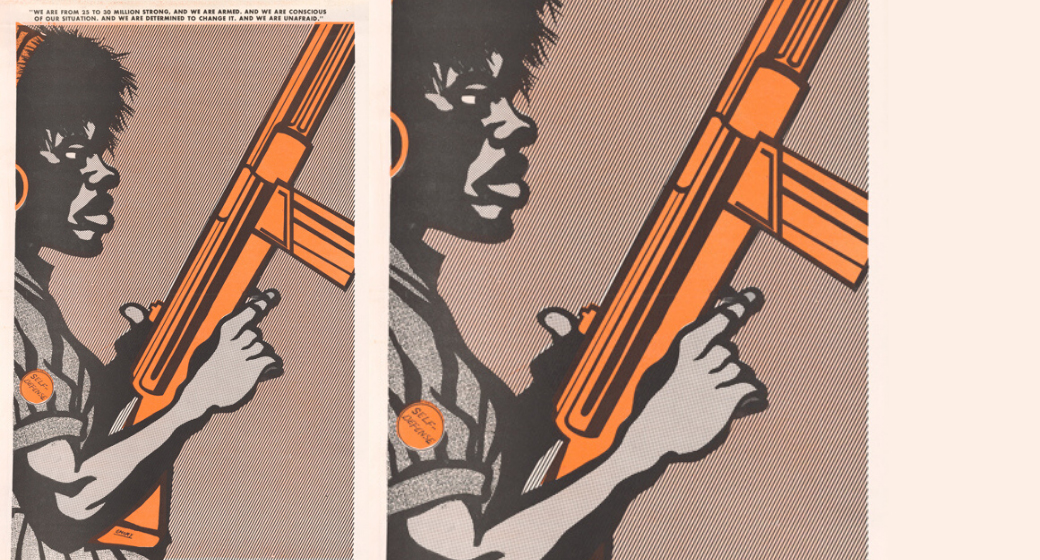

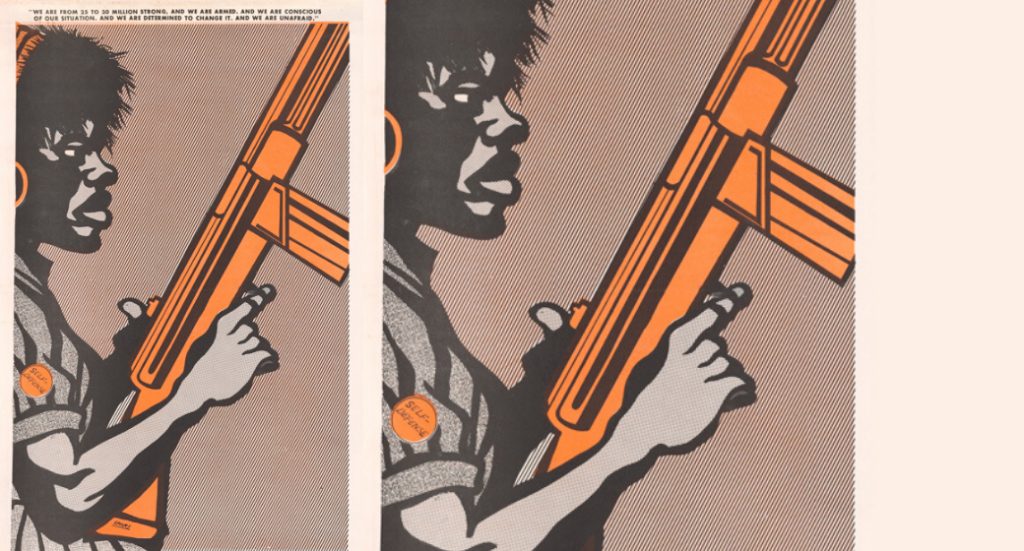

(American, b. 1943), Warning to America-We are 25-30 million strong, 1970, Offset lithograph on paper, 22 x 14 in., The Alfond Collection of Art, Gift of Barbara ’68 and Theodore ’68 Alfond, 2017.15.7. Image courtesy of the artist.

Born in Grand Rapids, Michigan, Emory Douglas moved with his mother to San Francisco when he was eight. At age 21 he began taking commercial art classes at City College, working as a designer and printer at local advertising agencies and community print shops. He was a frequent visitor to the Black House, a cultural center co-founded by future Black Panther Minister of Information Eldridge Cleaver, where he also met Bobby Seale and Huey Newton. Douglas took part in several of the early actions of the Black Panther Party and contributed his graphic design and printing skills to the Black Panther, the group’s influential weekly underground newspaper. As Black Panther Minister of Culture Douglas was responsible for the paper’s visual style, which combined the iconic forms of commercial advertising with the aesthetics of revolutionary poster art from anti-colonialist movements in Asia, Africa, and Latin America.

Douglas’s goal—realized in the pages of the newspaper and on standalone posters—was to create an aesthetic that would allow as many everyday African American people as possible to identify with his figures. These posters, which the BPP distributed in the tens of thousands to Black neighborhoods during the late 1960s and early 1970s, present a vison of powerful Blackness that Douglas envisioned as a pointed repudiation of the peaceful and accommodationist rhetoric of the Civil Rights Movement. The Black Panther Party for Self-Defense, as it was originally called, was formed in response to police harassment and brutality, and saw the protection of Black people against police abuses—including murders—as the absolute core, foundational effort of its revolutionary praxis. Frustrated by the inability of the Civil Rights movement to prevent these ongoing abuses, Douglas joined Newton, Seale, and other members of the BPP in advocating that Black citizens organize patrols to monitor police activity in Black neighborhoods, though their ability to do so was curtailed by a 1967 law that banned the open carrying of firearms in California. In a 2017 interview with the activist, curator, and performance artist Jarrel Phillips, Douglas explicitly connected the activism of the late 1960s and early 1970s to today, noting that Black Lives Matter and other protest movements have arisen out of the same rage at ongoing police abuses.

RMA owns several of Douglas’s posters from The Black Panther. Warning to America-We are 25-30 million strong is one of the most iconic of the group. Depicting a grim-faced African American woman in profile view, the poster is a masterclass in economy of form and color. Douglas was one of the first artists to depict Black people using the visual style of midcentury commercial art, and the figure’s full lips, natural hair, and dark skin were intended to help the newspaper or poster’s audience to identify with the BPP’s revolutionary aspirations towards an armed and self-sufficient Black populace. The gun, modeled after the AK-47 that was and remains a popular choice among insurgents and revolutionaries, is rendered disproportionately large, emphasizing its iconic, sinister stopping power. The button on the woman’s sleeve, which reads “Self Defense,” is formally united with the gun by Douglas’s use of bright orange pigment, both of them standing out in sharp contrast to the muted tones of the woman’s skin and clothing. Though the BPP has often been noted for its tough, macho aesthetic, Douglas’s drawings and poster frequently feature Black women, indicating his and the Party’s awareness that an activated Black revolutionary lumpenproletariat would require the participation of women.

Grant Hamming, Ph.D.

American Art Research Fellow

See Emory Douglas’s work on our Collection page.